Extreme horror has been a part of Asian film landscape for decades. From Hong Kong’s notorious category III films, to the gruesome world of the Guinea Pig series, there is a myriad of styles and titles to choose from. In this article, I have tried my best to collect together some of the most infamous films ever made. As this is quite a mammoth task, undoubtedly many deserving titles are missing, but I hope this little list will serve as starting point for those wanting to familiarize themselves with the more extreme side of Asian horror.

Extreme horror has been a part of Asian film landscape for decades. From Hong Kong’s notorious category III films, to the gruesome world of the Guinea Pig series, there is a myriad of styles and titles to choose from. In this article, I have tried my best to collect together some of the most infamous films ever made. As this is quite a mammoth task, undoubtedly many deserving titles are missing, but I hope this little list will serve as starting point for those wanting to familiarize themselves with the more extreme side of Asian horror.

China

When talking about extreme Asian cinema, the mind very quickly goes to China. In 1988 Hong Kong passed a film censorship law creating a new set of film classifications, of which category 3, or CAT III, was strictly preserved to those over the age of 18. The film that worked as a catalyst for these laws being drafted was T. F. Mous’ Men Behind the Sun (Hei tai yang 731, 1988). Depicting the horrors of that went on in the prison camp Squadron 731 during the Second World War, it is a truly disturbing viewing even in todays standards and it’s quite easy to see why a film such as this (which among other things features a real-life autopsy), would get any government body to rethink their censorship laws. Of course, Men Behind the Sun was not a first film containing graphic content, and many films made prior to 1988 were given the rating after the fact.

Films like Lewd Lizard (Chong, 1979), a story of a young man scorned by love, who goes on a killing spree using lizards as his weapon, featured the same kind of misogyny and bizarre sexual violence that is commonly seen in post 1988 CAT III films. Similarly, Dennis Yu’s 1980 hickploitation The Beasts (Shan kou) also earned itself the same rating with its scenes of gang rape and the onslaught of revenge-based violence that follows. More traditional kind of horror was also targeted and supernatural titles such as Centipede Horror (Wu gong zhou, 1982) and Devil Fetus (1983), both of which are relatively tame by today’s standards, were also slapped with the same harsh rating. However, the production of CAT III films really hit its stride in the 1990’s and it is estimated that 25 percent of all Hong Kong cinema of that time was indeed under the CAT III classification.

Films like Lewd Lizard (Chong, 1979), a story of a young man scorned by love, who goes on a killing spree using lizards as his weapon, featured the same kind of misogyny and bizarre sexual violence that is commonly seen in post 1988 CAT III films. Similarly, Dennis Yu’s 1980 hickploitation The Beasts (Shan kou) also earned itself the same rating with its scenes of gang rape and the onslaught of revenge-based violence that follows. More traditional kind of horror was also targeted and supernatural titles such as Centipede Horror (Wu gong zhou, 1982) and Devil Fetus (1983), both of which are relatively tame by today’s standards, were also slapped with the same harsh rating. However, the production of CAT III films really hit its stride in the 1990’s and it is estimated that 25 percent of all Hong Kong cinema of that time was indeed under the CAT III classification.

It is during this decade that directors like Herman Yau and Billy Tang would make their mark on the world of extreme cinema. Yau’s The Untold Story (Bat sin fan dim: Yan yuk cha siu bau, 1993), a loosely (and I do mean loosely) fact-based tale of torture, rape, murder and cannibalism, as well as his 1996 infection horror Ebola Syndrome (Yi boh lai beng duk), both still manage to shock and disgust audiences today. Tang’s better-known titles include Dr. Lamb (Gou yeung yi sang, 1992), a story of a psychotic taxi driver on a misogynistic killing spree, Run and Kill (Wu syu, 1993), a brutal crime story of a man on a vengeful mission and Red to Kill (Yeuk saat, 1994), a rape-revenge fantasy taking place in a home for children with learning difficulties, all titles that you will assuredly come across when researching Cat III cinema.

Japan

What would extreme horror be without Japan? After all, it is the birth place of some of the weirdest, sickest, most disturbing films ever made. For most people, myself included, the first films that come to mind are of course the infamous Guinea Pig (Ginî piggu) series.

Based on a manga works of Hideshi Hino (who also subsequently produced and directed two of the sequels: Flower of Flesh & Blood and Mermaid in a Manhole) it’s a six-part series that gained its notoriety not only for its graphic content, but for the fact that after the first two films the producers had to prove that their actors were still very much alive.

The main focus of the series is in depicting most brutal torture one can imagine and the first two films Guinea Pig: Devils Experiment (Ginî piggu – Akuma no jikken, 1985) and Guinea Pig 2: Flower of Flesh & Blood (Ginī Piggu 2: Chiniku no Hana, 1985) do just that, both revolving around a kidnapping and subsequent torture – scenario. The third installment Guinea Pig 3: Shudder! The Man Who Doesn’t Die (Ginī Piggu 3: Senritsu! Shinanai otoko, 1986) still has a kidnapping element to it, but changes the pace a bit and instead of telling a tale of innocent victim getting hacked into pieces, it’s a story of a man who after realising that he cannot feel any pain, decides to cut, slice and chop himself into bits while his horrified co-worker bears witness to the surreal ordeal. Guinea Pig 4: Devil Woman Doctor (Ginī Piggu 4: Pītā no Akuma no Joi-san, 1986) was the fourth film to be produced, but the sixth to be released and changed the overall tone of the films from extreme violence to bizarrely savage slapstick comedy.

The last two films The Guinea Pig 5: Android of Notre Dame (Ginī Piggu 2: Nōtorudamu no Andoroido, 1988) and Guinea Pig 6: Mermaid in a Manhole (Ginī Piggu: Manhōru no naka no Ningyo, 1988) both took the series in their own equally weird direction, Android being a story about scientific experiments (on humans, of course) gone horribly wrong and Mermaid (the only story directly based on one of Hino’s mangas) a story of a recently widowed man who befriends a mermaid living in the local sewer. Since their release the series has spawned two making of documentaries (Making of Guinea Pig and Making of Devil Woman Doctor), several specials showcasing the worst bits of the six films and an American spinoff series American Guinea Pig (2014-2018) consisting of four films of similar ilk.

The last two films The Guinea Pig 5: Android of Notre Dame (Ginī Piggu 2: Nōtorudamu no Andoroido, 1988) and Guinea Pig 6: Mermaid in a Manhole (Ginī Piggu: Manhōru no naka no Ningyo, 1988) both took the series in their own equally weird direction, Android being a story about scientific experiments (on humans, of course) gone horribly wrong and Mermaid (the only story directly based on one of Hino’s mangas) a story of a recently widowed man who befriends a mermaid living in the local sewer. Since their release the series has spawned two making of documentaries (Making of Guinea Pig and Making of Devil Woman Doctor), several specials showcasing the worst bits of the six films and an American spinoff series American Guinea Pig (2014-2018) consisting of four films of similar ilk.

Another film series worthy of a mention in this particular context is Katsuya Matsumura’s All Night Long (Ooru naito rongu).

Like The Guinea Pig series, it also spanned over six episodes, although the first three are often times the only ones that get a mention. The first of the series, simply titled All Night Long (1992) earned Matsumura the best new director award at the Yokohama Film Festival. It’s a story of three youngsters brought together by witnessing a mindless act of violence and who then go on their own personal rampage in the Tokyo underworld. While revenge is the motivation behind the main characters violent behaviour, there is no satisfaction to be had from their mission of violence. Instead the whole story is a rather nihilistic look on humanity and modern society as a whole, the main message of the film being that all people are terrible and equally capable of violence no matter what their background.

Like The Guinea Pig series, it also spanned over six episodes, although the first three are often times the only ones that get a mention. The first of the series, simply titled All Night Long (1992) earned Matsumura the best new director award at the Yokohama Film Festival. It’s a story of three youngsters brought together by witnessing a mindless act of violence and who then go on their own personal rampage in the Tokyo underworld. While revenge is the motivation behind the main characters violent behaviour, there is no satisfaction to be had from their mission of violence. Instead the whole story is a rather nihilistic look on humanity and modern society as a whole, the main message of the film being that all people are terrible and equally capable of violence no matter what their background.

While the film is not overly gory, the shear bleakness of the plot makes it a pretty uncomfortable watch. After the success of the first film, Matsumura went on to direct five more instalments for the series; All Night Long 2: Atrocity (Ooru naito rongu: Sanji, 1995), All Night Long 3: The Final Chapter (Ooru naito rongu 3: Sanji, 1996), Ôru naito rongu R (2002), All Night Long: Anyone Would Have Done (2009), all of which more or less continue in the same nihilistic world view as their predecessor. Some have the element of revenge in the storyline, but it’s again not in any shape or form a saving grace for the characters behind it.

Kichiku: Banquet of the Beasts (Kichiku Dai Enkai, 1997) is equally a title synonymous with extreme horror cinema. It makes its way to nearly every listing of goriest films, and for a good reason; among other things it features such delights as shotgun blasts to the face, castrations and partials beheadings. However, what sets this kaleidoscope of brutality apart from other gore porn, is that it, rather weirdly, was the director Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s thesis project! Something quite unthinkable here in the west and definitely something that leaves you wondering with what kind of grade did Kumakiri graduate with?

Moving towards the end of the century, 1999 brought with it films like Muzan-e (Muzan-e: AV gyaru satsujin bideo wa sonzai shita!) and Womens Flesh – My Red Guts (Watashi no akai harawata (hana)). Muzan-e (also known as Celluloid nightmares) plays around with the idea of snuff film and what happens to nosy reporters who investigate this ill-famed subject too deeply.

The director Daisuke Yamanouchi has taken the road less travelled (in that particular point in time) and rather than making a straight forward gore fest, the story is told in mockumentary format; a rather nice touch considering the subject matter. However, mockumentary or not, Muzan-e still has plenty of gross out scenes to offer, including some rather bizarre menstrual fetish porn, which most definitely will not be everyone’s cup of tea. Meanwhile Womens Flesh by Tamakichi Anaru will take the viewer to completely different kind of trip; the kind you are not likely to want to repeat. The film, all the 41 minutes of it, consists of two women (played by the same actor) slowly mutilating themselves to death and features such pleasures as violent masturbation with a toothbrush, chewing off body parts, stabbing, slashing and removal of entrails. Not for the weak of heart, that is for sure.

The director Daisuke Yamanouchi has taken the road less travelled (in that particular point in time) and rather than making a straight forward gore fest, the story is told in mockumentary format; a rather nice touch considering the subject matter. However, mockumentary or not, Muzan-e still has plenty of gross out scenes to offer, including some rather bizarre menstrual fetish porn, which most definitely will not be everyone’s cup of tea. Meanwhile Womens Flesh by Tamakichi Anaru will take the viewer to completely different kind of trip; the kind you are not likely to want to repeat. The film, all the 41 minutes of it, consists of two women (played by the same actor) slowly mutilating themselves to death and features such pleasures as violent masturbation with a toothbrush, chewing off body parts, stabbing, slashing and removal of entrails. Not for the weak of heart, that is for sure.

Coming into the noughties the film making legend Takashi Miike shocked audiences with his little family drama called Visitor Q (Bijitâ Q, 2001). Out of Miike’s extensive catalogue, it is definitely a film that will stand out in your mind. Perhaps not so much for the violence as Ichi the Killer (also 2001) might have, but more for it’s extremely perverted, yet, somehow darkly humorous storyline. Familial abuse, incest, drug addiction and deeply disturbed and flawed characters, Visitor Q certainly has it all. Towards the latter part of the decade the horror legend Kôji Shiraishi also decided to try his hand in the more extreme side of cinema and created a film called Grotesque (Gurotesuku, 2009).

It’s simply a “story” of a demented doctor that kidnaps a couple and then carries on torturing them in any way imaginable. It offers next to no plot and pretty much zero character development, as the main focus of the film is firmly on depicting the various methods of torture. A complete divergence from Shiraishi’s earlier work, the film was banned in Norway and British Board of Film Classification refused to issue an 18 certificate, therefore essentially banning its release in the UK; a reaction that Shiraishi himself was allegedly “delighted and flattered by”.

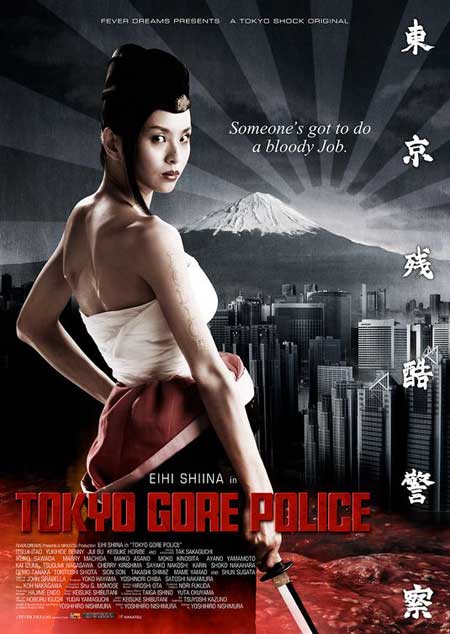

For those who prefer their extreme horror more in the humorous side, Japan has plenty to offer. Titles like Tokyo gore Police, and Meatball Machine offer unbelievably over the top violence combined with tongue in cheek action and mind bogglingly imaginative special effects. If you’re looking for extreme violence without the soul crushing nihilism, these titles are definitely the ticket. A good name to keep a look out for is Yoshihiro Nishimura, the man not only behind the Tokyo Gore Police, but also an immense amount of incredible special effects work in several different films of similar ilk. Once you see his style, you will learn to recognise it and love it.

Korea

Korea

If you have ever wondered why it is nearly impossibly to find any Korean horror pre 1990’s, you are not alone. It’s certainly a question that has riddled my mind in the past. It’s not for the lack of your research skills though, as I at some point thought. The answer lies in the highly strict censorship rules enforced by the South Korean government in the 1970’s. Only filmmakers deemed ideologically fit were allowed to release new films and the propaganda heavy content they were made to produce left very little room for creativity and certainly no rooms for genres like horror. However, After the falling numbers in the box office, the government started to loosened its grip and by the late 1980’s the doors were open to independent directors, as well as previously banned foreign films. The 1997 Asian financial crisis moved things along furthermore, and helped to shape South Korean cinema as we know it today.

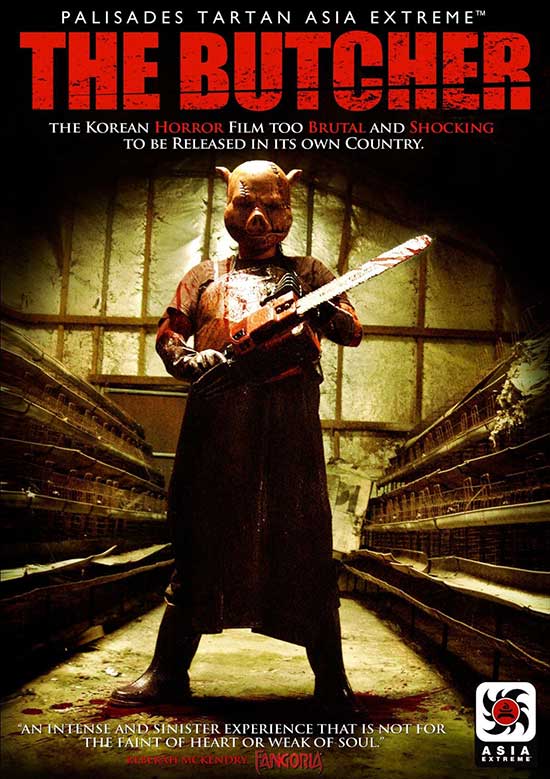

While South Korean horror is perhaps best known for psychological thrillers and murder mystery ghost stories, there is a few more extreme titles that are worthy of a mention is this particular context. Kim Jin-won The Butcher (2007) is certainly something that will stick in most people’s minds, and not necessarily in a good way. It is another take on the snuff film theme, this time showing the action from the point of view of both the torturer and his victims, adding an extra layer of terror to the mix. Among other things it features dismemberment of limbs and very graphic eye gouging, none of which makes for particularly pleasant viewing. However, for those after something with real shock value, a worthy watch. 2010 saw the release of two extreme thriller/horror films, Bedevilled (Kim Bok-nam salinsageonui jeonmal) and I Saw the Devil (Ang-ma-reul bo-at-da), both horrific in their own special way. Cheol-soo Jang’s directorial debut Bedevilled, a story of abuse and revenge, is a gut-wrenching watch.

While graphic, it’s not so much the violence that gets you, as the horrifically ugly nature of almost all of the characters (including the main character Hae Won). It’s a truly nasty depiction of the lengths people go to, to avoid helping someone. I Saw the Devil by one of Korea’s best-known directors Jee-woon Kim is equally unrelenting tale of revenge, but with a slightly less anxiety giving premise.

In it a NIS agent Kim Soo-hyun embarks on a deadly cat and mouse game with a serial killer that has made the mistake of murdering his beloved fiancée. Pretty much all of the films 142-minute running time is just relentless violence, but unlike most of the violence in Bedevilled, there is a certain amount of satisfaction to this brutality. The film is beautifully executed in all fronts and although it might sound like it, is not just mindless bloodshed, but also has a very well build story behind it. Absolute must watch for any fans of Korean horror.

Indonesia

Indonesia

Due to lack of release outside the country’s own boarders, Indonesian horror has remained largely unknown for most western viewers until relatively recently. Mostly focused on black magic and traditional folklore, there is a great plethora of films that still continue to elude us here in the west, but while we eagerly wait for someone to release some of those gems in the DVD/Blu-ray format, there is a few films that have seen their release in more recent years that are definitely worthy of one’s attention. Directed by Kimo Stamboel and Timo Tjahjanto (as The Mo Brothers) the 2009 film Macabre (Rumah Dara) is a blood-filled tale of a group of unlucky travelers who make the mistake of accepting a dinner invitation from the worst kind of family.

Essentially a splatter film Macabre offers a lot of good old extreme violence, but doesn’t take itself overly seriously. Compared to some other films on this list, it’s a hell of a lot lighter watch and a bloody good time. Another recent title, also brought to us by Mr. Tjahjanto, is the 2018 May the Devil Take you (Sebelum Iblis Menjemput). When a family patriarch falls into a mysterious coma, his children go on to seek answers in an old family villa, only to find some rather dark family secrets. Despite being produced by Netflix, it is a surprisingly violent supernatural romp in the style of Evil Dead, that offers plenty of possession induced brutality and off the wall action. And while on the subject of Tjahjanto and Netflix, it is worth mentioning another Netflix original by the same man; The Night Comes For Us (2018), a gangland story of ones mans desire to break free from his old life. While not horror, it is definitely in the more extreme side of cinema and if you are a fan of the Gareth Evans’ The Raid Films, this will surely be your cup of tea.

I hope this article has offered a little bit of insight into the world of extreme Asian horror. Many of the titles mentioned here can be hard to come by, but if you are not overly fussy on quality, quite a few can be found on Youtube (for example, much to my surprise I managed to find Dennis Yu’s The Beasts lurking around in there, but the picture and sound quality is atrociously bad). For more info about CAT III films and a more comprehensive list on the subject check out Adrian Halen’s article CAT III (Category 3) & Extreme Asian Film.

See other article for listing of films – CAT III extreme Asia

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Hi. Love the article. I already know some of the titles you mentioned but wouldn’t dare sitting through most of them. But in the Japan section, I am quite surprised not to see Niku Daruma. Obviously I have yet to watch it but most reviews I have read suggested that one is one gory flick. Anyway, again, great article!