Cyberpunk is an offshoot of science fiction, usually set in a dystopian future with a focus on “low life-high tech”; advanced technology in contrast with dire living conditions, pollution and social disorder. The genre has it’s beginning in the 1960’s and 1970’s with authors like Phillip K. Dick, Roger Zelazny and J. G. Ballard taking science fiction to darker paths from utopian tales that preceded them. While for most people the word cyberpunk most likely brings to mind Riddley Scott’s 1982 masterpiece Blade Runner, there is a plethora of films just as, or perhaps even more important, that came out of Japan around the same time.

Admittedly, the Japanese take on the genre is something quite unique and does not fully follow the same avenues as western films. The live action side of Japanese cyberpunk is filled with films with nearly incomprehensible stories and dizzying visuals and the animated part offers a lot more philosophical take on things than viewers might be expecting. However, it is a side of the genre that I fully recommend anyone with an interest to explore. It’s rich, deep, utterly bizarre and full of absolute cinematic brilliance.

Horror News offers many more Asian Movie Articles, make sure and check them out!

To ease oneself into Japanese cyberpunk, one might be better off starting from the world of anime. While the animated films and TV series still explore very much the same concepts that you would see in the live action side of cinema and are for the most part definitely aimed at more mature audiences, many of them offer a slightly more straight forward take on the themes prevalent in the cyberpunk movement.

Like the live action genre, the origins of cyberpunk anime can be found in the 1980’s. It stemmed from the works of manga artists such as Katsuhiro Otomo (Akira, 1982) and Shirow Masamune (Appleseed, 1985, Ghost in the Shell, 1989), whose literary work would go on to be adapted in the animated format and becoming some of the most seminal pieces of cyberpunk genre.

But of before diving into heavier works like Akira and Ghost in the Shell, let’s have a brief look at some other animated titles that navigated the grimy waters of cyberpunk. In 1985 AIC (Anime International Company) brought out a four-part original series called Megazone 23 (Megazōn Tsū Surī) that can almost be seen as precursor to Matrix. In it a delinquent motorcyclist Shougo Yahagi finds himself in a possession of secret government technology (an experimental motorbike/weapon). The more he looks into the origins of this mysterious technology, the more he finds out that the world around him is not quite as it seems. The concepts of fake reality and human race destroying itself through environmental abandon and endless wars are prevalent and certainly have lot to answer for when it comes influencing more modern pieces of science fiction/cyberpunk cinema. The animation isn’t the best quality, at points teetering on terrible, but if you have an interest in stories about fake realities, this could be a title for you.

In 1993 Yukito Kishiro’s nine-part manga series Battle Angel Alita, also known as Gunnm or Ganmu had its first two chapters turned into two-part animation. The story, set in the dim and distant future, follows a female cyborg named Alita who has lost her memory. After being found in a junkyard by a cybernetics doctor she slowly starts to piece her past together and along the way finds out that she, among other things, is quite skilled in martial arts. This leads her to pursue a career as bounty hunter, going after cyborg criminals. Alita encompasses many of the classic cyberpunk themes such as a world deeply divided to the haves and have nots; the people of the floating city of Tiphares and those who live bellow in the garbage heap called Scrapyard. It also explores the age-old question if what truly makes us human through Alitas eyes. While the short running time is a slight obstacle in the way of more profound look of the themes, Alita is visually closer to the style that most people would associate with cyberpunk, albeit Japanese or Western version of it.

There’s a griminess to it that seems to be missing from the clean-cut worlds of Megazone 23 or Appleseed. The animation is at parts somewhat lazy, shamelessly utilising still images (as so many of the animes from this era do), but the artwork is beautifully stylized and a pleasure to watch. It’s dark and filthy, just like a good cyberpunk story should be. While most titles mentioned here are more or less violent, Alita is definitely one of the bloodier ones, fully revelling in the bloodshed. There are beheadings, bodies ripped apart and all sorts of extreme violence that will surely enthral fans of more extreme kind of cinema. Those wanting to see more of Alita and her companions can chance their luck with the brand spanking new American live action version of the story Alita: Battle Angel (2019) directed by Robert Rodriquez.

In 1987one of the aforementioned Shirow Masamune’s earlier cyberpunk works Black Magic M-66 (M-66 Burakku Majikku Mario Shikkusuti Shikkusu) was adapted in the animation format. The 48-minute anime is loosely based on one of the chapters of the manga and follows a female journalist Sybel, as she tries to protect a young woman from a military android out for her blood. It doesn’t really contain the key elements usually associated with cyberpunk such as “low life-high tech” but as the original manga is very much counted as a part of the genre, I felt its animated version deserved a mention.

The following year Masamune’s other earlier cyberpunk series Appleseed (Appurushīdo) got its OVA release (original video animation: animated films and TV series made especially for home video release) and again, the animated adaptation takes a fair few liberties with the original material as the four-part manga series has been reduced to mere 70 minutes. The story is set in an experimental city of Olympus, which by all standards should be a utopian paradise.

The city, build after World War III has ripped through the planet leaving it in smouldering rubbles, is occupied by humans, cyborgs and a new species called biodroids; a genetically modified beings that were created to administrate Olympus and serve mankind. While on surface everything seems hunky dory, not all Olympians think that their new home the paradise that they have been sold. Among those who see the never-ending pleasantness somewhat unnerving and even inhumane, is police officer Calon Mautholos, who after his wives’ suicide has started to question whether Olympus is the right place for human beings. Joining forces with a terrorist called A. J. Sebastian, he sets out to destroy the city’s supercomputer Gaia. Lucky for Olympians, standing on their way are two members of Olympus’ ESWAT (enhanced SWAT) team Deunan Knute and Briareos Hecatonchires who have sworn to protect the city and its citizens. The story follows Deunan and Briareous as they chase down the terrorists and try to solve who in the police force has defected to the other side. Along the way Deunan becomes to question the nature of Olympian living herself.

Besides the utopian world verses the horrors of outside, futuristic technology and human/machine hybrids, Appleseed takes a stab at exploring some of the deeper themes prevalent in the genre, such as what qualifies as truly living, taking somewhat Taoist outlook on the concept and pondering whether living in a world where everything is well all the time, is actually living or merely existing. The so-called perfect world might be perfect for the biodroids that were created for it, but for humans with all their imperfections, it can become more of a gilded cage. Unfortunately, none of this is ever examined with any great detail and the focus of the anime is very much on action. It’s of course understandable considering its relatively short running time, but you can’t help but to feel somewhat short-changed by the way the ending of the story seems to completely ignore any of the deeper themes introduced earlier on.

That’s not to say Appleseed is a complete waste of time, in fact it’s quite an entertaining watch (as a side note I would like to mention though, that it’s not necessarily safe to watch with the youngest of the family as the English translations weirdly contains a substantial amount of profanity), but for those looking for something more serious, might have revert back to the original manga. However, if you wish, you can delve a little deeper into the animated world by checking out the 2004 CGI reboot by Shinji Aramaki also titled Appleseed, and its sequels Appleseed Ex Machina (2007) and Appleseed Alpha (2014).

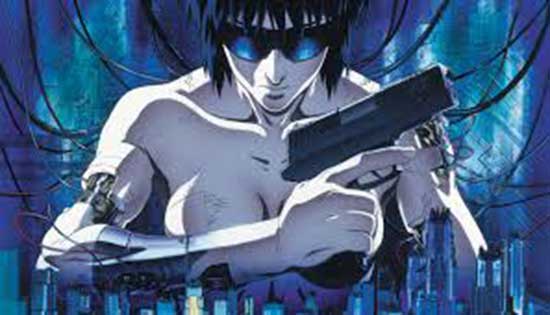

Masamune’s best known work in the world of cyberpunk is of course Ghost in the Shell (Kôkaku Kidôtai), made famous by the animated version directed to big screens by Mamoru Oshii in 1995. If you grew you in the 1990’s and had even a hint of an interest in science fiction, you would have been hard pressed to not come across this film. And for a good reason of course; alongside Akira, Ghost in the Shell is one of the most fundamental cyberpunks anime’s ever made. Set in 2029, in a world where most of the population consists of cyborgs and human beings “enhanced” by cybernetic technologies, the story follows a cyborg assault team leader Major Motoko Kusanagi who together with her partner tracks down an international hacker called “Puppet Master”. In their quest to hunt down a criminal with no actual living body, Motoko finds herself questioning the very essence of her own being, which in turn leads her path in an unforeseen direction.

As you might have already gathered, the theme of humanity and what really makes us human is heavily present in the film. It draws from the philosophical idea of duality in which body and the mind, or “soul”, exist as separate entities. Just like the bodiless Puppet Master, in essence Motoko herself only exist as a virtual being that can be transferred to a new body with a click of a switch, making her present host body somewhat irrelevant. How does this version of immortality relate to the human experience? No matter how well programmed, can Motoko or the Puppet Master ever really understand what it means to be human if they never truly inhabit a body that can die? And more importantly, do they have to, or is their experience of this reality just as valid and viable as that of a human? Safe to say, Ghost in the Shell dives into some pretty deep waters. Besides this rather philosophical take on the things, the film does also offer some pretty great action scenes and very well executed animation. It may not quite reach the same level of brilliance than Akira but it’s certainly not far off. A wonderful watch for those in a mood for something more ponderous.

And of course, you cannot talk about cyberpunk without talking about Akira (1988). Based on an eponymous manga by Katsuhiro Otomo, it is without a doubt one of the most influential, if not THE most influential, films of the genre. Starting in 1982 and not to be finished until 1990 the original comic version spanned over six volumes. The increasing popularity of the relatively new cyberpunk genre as well as the tremendous following of Otomo’s manga naturally meant that sooner or later his masterpiece would find its way to the big screen. Not wanting to hand his precious work over to just anyone, Otomo insisted on having creative control over the project. However, his ambitious vision for the film was too much for any one studio at the time and so something called Akira Committee was formed; a group of major production studios including Toho, Kodansha, Bandai and Hakuhodo (among others) came together to make Otomo’s vision reality.

With never before seen budget of $11 million it was the most expensive animated film of it’s time (and for a good while after too). But it’s easy to see that neither Otomo’s creative talent nor the money thrown at this project, were in any way wasted. Even today, 30 years after its release, the quality of the animation alone is something truly awe-inspiring. While many of Akira’s contemporaries would rely on cheap trick like panning across still images and having unwarranted sunglasses on all the characters in order to avoid animating eye movements, none of these hallmarks of lazy animation are present in Akira. It is pure animation gold from the backgrounds to the characters and everything else in between. This mind-bogglingly amazing animated experience is the outcome of over 160,000 animation cels (which was a LOT at the time) all painstakingly hand drawn. Unlike other films of the time, the dialogue for the film was also pre-recorded, letting the animators synch their material to the actors performances, rather than the other way around. All of this results in something so smooth, you’d almost think you’re watching a live action piece.

Besides the gorgeous artwork, it is of course the story that keeps on drawing people to this film. Quite topically, set in the year 2019 Neo-Tokyo (side note: the film also quite eerily predicts The Tokyo Olympics with banner advertising the 2020 event coming to Neo-Tokyo); Tokyo rebuilt after major explosion has destroyed most of the city, the story follows a young biker gang member, Tetsuo. After getting into an incident involving a rival biker gang and some government agents, he finds himself in possession of powerful psychic forces, but as it usually goes, powers of this kind do not come without a price, and in spite of his best efforts, Tetsuo is soon overwhelmed by powers too great for any one human to handle.

Thematically there is a lot to unpack and naturally the themes of Akira have been theorized about for decades. The anxieties of post war Japan are prevalent straight from the dramatic opening sequence and the references to horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are obvious. Beyond this the film explores other common cyberpunk themes such as loss of humanity and the corruptive influence of power, as well as friendship, loyalty and jealousy. I don’t think I can emphasise enough the importance of this film. While there are other notable films found in the genre, none of them quite compare to Akira. It embodies the whole genre in an almost perfect manner and does it with stunning visuals and a well build story arc that sucks you in right from the very first frames. It’s still today considered one of the greatest science fiction films ever made, frequently receiving high rankings in various sci-fi listings over the world and has naturally gone on to inspire numerous sci-fi and cyberpunk films. Absolute must see for everyone.

While the world of comics and animation have had a major influence in the development of Japanese cyberpunk cinema, the origins of the live action genre can somewhat surprisingly be found in the world of music. From the vibrant punk rock scene of Tokyo came artists like Sogo Ishii (real name Gakuryū Ishii) who in they attempt to bring the spirit of punk rock into the silver screen, also ended up creating something that would go on to inspire a whole new style of film making. Like most independent filmmakers of the time, Ishii worked on 8mm film and next to no budget, but quite quickly made a name for himself in the underground film scene.

His early works Panic High School (Koko Dai Panikku, 1978) and Crazy Thunder Road (Kuruizaki sanda rodo, 1980) are not so much cyberpunk as they are punk rock/biker films, but have been a major influence in the style of the genre, and the echoes of their aesthetics can be seen in films such as Akira. The reputation of these pieces helped Ishii not only to gain a distribution deal with a major studio (Toei), but also to get his next major project, Burst City (Bakuretsu toshi, 1982), financed by them. With Burst City Ishii was finally able to create a film that epitomized his beloved punk rock movement, while at the same time creating a piece that would become a precursor of Japanese cyberpunk cinema. It’s a dystopian tale if punk rock gangs battling with each other as well as the brutal local police force and like Ishii’s earlier work, is still eminently driven by the punk rock music scene featuring actual bands of the time like The Rockers, The Roosters and The Stalin as part of the cast.

Amongst the various artists featured in Burst City was also the folk singer Shigeru Izumiya, who four years later would go on to write and direct his own cyberpunk vision and a film that would cement many of the aesthetic conventions seen in later cyberpunk classics: Death Powder (Desu pawuda, 1986). It’s a story of a group of researchers who have gotten access to a female android with a power to spew out a poisonous powder. Although the word story might be slightly misleading here, as Death Powder is quite well known for its extremely hard to follow, almost incoherent plot. This is partly due to the lousy quality translation that for years has been the only version available for western audiences, but as the film is not very heavily reliant on dialogue, the pitifully poor subtitles are only a part of the film’s baffling nature. Everything from its chaotic, abstract imagery to a soundscape that seems to assault your senses makes it a mystifying watch to say the least, but it’s influence on the genre is undeniable. Amongst the chaos the themes of mutation of flesh and metal and the questions of what makes us human seep through. It also sets a precedent for emphasizing visuals over a cohesive story, letting the wild, sometimes bewildering imagery take the viewer on a strange journey; something that subsequent filmmakers such as Shin’ya Tsukamoto would readily use in their films.

And Tsukamoto of course is the name that pops to most people’s mind when talking about Japanese cyberpunk. He seminal work in the genre, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (Tetsuo, 1989), can quite safely be seen as the epitome of everything that the cyberpunk movement represents and has in its part been as big an influence on the development of the genre as Death Powder. Tsukamoto got interested in filmmaking at the age of 14, when his father gifted him a super 8 camera. For years he produced films ranging from just a few minutes to two hours long epics.

While in college Tsukamoto took a brief detour to the world of theatre and together with Kei Fujiwara, Nobu Kanaoka and Tomorowo Taguchi (among others) created a piece of “kaiju theatre” called The Adventures of Electric Rod Boy (Denchu kozo no boken).

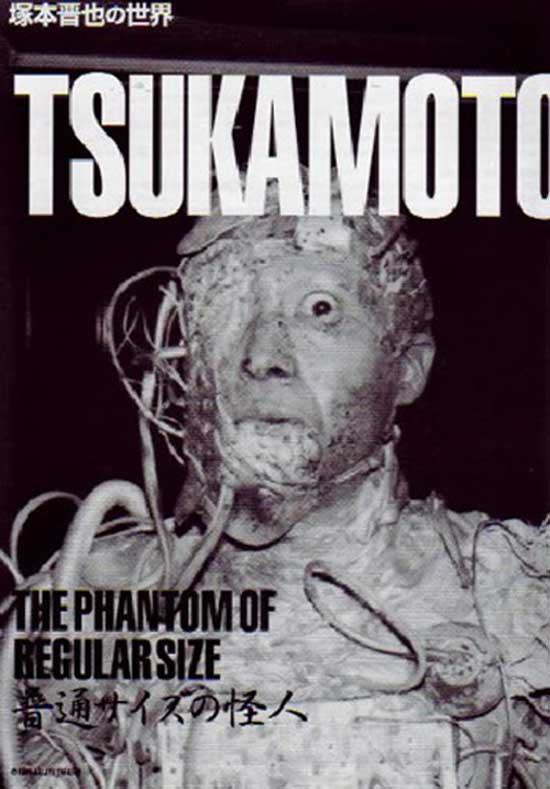

Not wanting to waste perfectly good set pieces, Tsukamoto would go on to adapt the story in the cinematic form in 1987. However, before that he produced a short film called The Phantom of Regular Size (Futsû saizu no kaijin, 1986) which can very much be seen as a practice run for Tetsuo. Much like Tetsuo, it tells a tale of a man who is slowly turning into a metal encrusted monster, but with only 18-minute running time, there isn’t a significant amount of story to be getting on with. The feel of the film is much more like an experimental student project rather than anything professionally produced, and the effects used have a distinctly home-made look about then. Despite that, for Tsukamoto fans it makes in interesting watch, as it does offer and compelling insight to the origins of one of the best cyberpunk movies ever made.

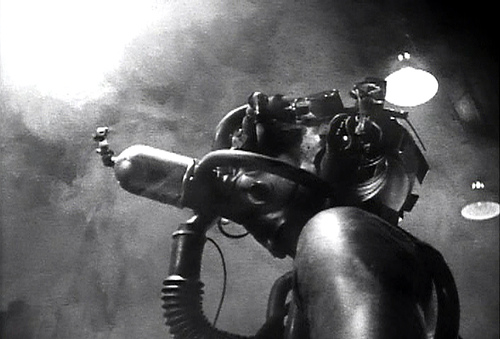

The following year Tsukamoto went on to direct the aforementioned Denchu kozo no boken, a story of a young boy with a electricity pole growing of his back, who gets sucked into a hellish dystopian future where the streets of Tokyo are ruled by ruthless Shinsengumi vampire gangs that plan to plunge the whole world in permanent darkness with the help of their doomsday device Adam. Only Electric rod boy can stop them and bring light back to the world. Mere 47 minutes long, but still dizzyingly fast paced watch, Denchu kozo no boken takes a bit more of a stab at a followable plot and doesn’t leave the viewer quite as confused as The Phantom might. That being said, it’s still very much a mad bombardment of the senses and moves at such speed (plot and imagery wise) that it is in parts fairly difficult to keep up. There’s a definite development in style and it’s obvious that Tsukamoto has started to work out the kinks of his stop motion sequences as well as the metallic special effect nightmares. While the plot might run away never to be seen again, the animation is a joy to watch and some of the best scenes of the film are indeed found amongst the stop motion. Thematically it explores very much the same areas as The Phantom; the vampires featured in the film are not just any garden variety blood suckers but half vampire, half machine hybrids and neither is their doomsday device powered by traditional means, but by a young girl that has been hooked up to the machine since birth, thus continuing the theme of mutation, humanity and connection between men and technology.

Two years later, in 1989, Tsukamoto finally fully realised all these ideas and themes in Tetsuo: The Iron Man. In it an unfortunate businessman (Tomorowo Taguchi) accidently drives over a mysterious Metal Fetishist (Tsukamoto himself), who as revenge starts to mutate the man into a mix of flesh and metal. While the story is still told in Tsukamoto’s trademark style of chaos and fast paced imagery, Tetsuo has much more structure than its predecessors. The story, while enigmatic, is still followable and Tsukamoto has clearly finally found the rhythm that he has been looking for. The imagery is dynamic and sharp, hitting the sense like a hammer. Chu Ishikawa’s incredible industrial score completes the grotesque story perfectly. It’s a glorious piece of cyberpunk cinema that every fan of the genre should absolute see. While the production of Tetsuo was a tortured one, so much so that by the end of filming, only actors were left to finish the film, Tsukamoto went on to create two sequels: Tetsuo II: Body Hammer (1992) and Tetsuo: The Bullet Man (2009). Both are very much a reworkings of the original film and follow along similar plotlines as well as themes.

Another noteworthy name in Japanese cyberpunk cinema is Shozin Fukui. Like most filmmakers he started his career with short films directing experimental titles such as Gerorisuto (1986) following a young, possibly possessed, woman through the Tokyo subway system and Caterpillar (1988) a fairly incomprehensible short featuring a caterpillar-like monster lurking around streets of Tokyo.

The latter of the two with its fast paced hand held camera action and a monster assembled largely of what looks like tin foil, has definite resemblance in the early works of Tsukamoto, and it’s no surprise; Fukui was not only a contemporary of Tsukamoto, but actually worked as part of the crew on the set of Tetsuo. A few years after the success of Tsukamoto’s masterpiece, Fukui brought out his own feature length tale of cyberpunk madness in the form of 964 Pinocchio (1991) (also rather dramatically known as Screams of Blasphemy). In it, the titular Pinocchio, a brainwashed man that has been scientifically altered to be human equivalent of a sex doll, is tossed on the street by his dissatisfied owner. He soon meets Himiko, a homeless girl who takes him in and tries to help him to become fully functioning human being again.

Tetsuo and Pinocchio are often compared to each other and they certainly do share many similarities; the chaotic atmosphere and the theme of metamorphosis are prevalent in both as is the theme of invasive technology. However, that is not to say that Fukui would in any way be copying Tsukamoto’s work. While the two films co-exist in what could easily be the same, dark and dingy universe, Fukui’s unique cinematic language leaves no doubt about the originality of his work. The most obvious difference between the two is Fukui’s decision to use colour instead of the dark black and white, giving the film a much more real-life feel than what Tetsuo has. Both films are heavily focused on bodily metamorphosis but the reason behind these changes do differ from each other; while Tetsuo’s man-machine is a result of a kind of possession or technological virus if you will, Pinocchio’s evolution is a direct result from enhancements made by men. Pinocchio’s soundtrack is also a whole other level of terrifying; while Tetsuo’s story is punctuated and heightened by a fantastic industrial score, Pinocchio’s soundtrack largely consists of screaming (which I suppose explain the English title “Screams of Blasphemy”). It’s something truly disturbing, but quite frankly starts to get quite wearing after a while.

In 1996 Fukui followed Pinocchio with a title called Rubber’s Lover, that continued to explore similar themes. In it a group of illicit scientists experiment on people they kidnap from the streets. In their efforts to unlock hidden psychic powers they expose their victims to horrifying ordeals, that more often than not, result in deadly outcomes. Unlike its predecessor, Rubber’s Lover was shot in black and white, allegedly because of Fukui’s dislike of how the S&M costumes looked on colour film. The stark contrast of the black and white together with the industrial imagery that punctuates the story, gives a very bleak feel to the film. The gory violence, tortuous soundtrack and maniacal acting also do their part in adding to the dark atmosphere. The story is mad to the point of being completely incomprehensible, but still certainly one that is worth exploring in the context of Japanese cyberpunk.

A filmmaker with work slightly more recognisable for modern horror audiences, but whose roots are still undeniably in the cyberpunk movement is Yoshihiro Nishimura. While his work is perhaps best known in the world of special effects, having been featured in numerous films including aforementioned Rubber’s Lover, Suicide Club (Jisatsu sâkuru, 2001), Meatball Machine (2005) and The Machine Girl (Kataude mashin gâru, 2008) and earning him the nickname “Tom Savini of Japan”, Nishimura has also had a fair go at directing. Most genre fans have at least heard of his 2008 splatterpunk romp Tokyo Gore Police (Tôkyô zankoku keisatsu) but might not be aware of the origins of the film, going all the way back to 1995 and one of his early directorial efforts, Anatomia Extinction (Genkai jinkô keisû).

It’s a beautifully executed cyberpunk nightmare with vivid colour palate reminiscent of works of Bava or Argento, but still somehow keeping with grimy ambience of its predecessors. Set in indeterminate time in future, Tokyo is in the grips of an overpopulation crisis. To alleviate the problem, some individuals have taken to brutally murdering their fellow citizens and it is by witnessing one of these hateful crimes and being stalked by the killer, our main protagonist finds himself sucked into being part of the murderous uprising by a group called “The Engineers”.

Despite his efforts of resistance, he soon finds his body changing in bizarre ways and his appetite for killing increasing by the hour. The majority of the story is told via news reports of population statistics and gruesome murders shown somewhere in the background and bulk of the film relies more on visuals than dialogue. This is of course nothing unusual in the cyberpunk genre, but particularly significant when talking about Nishimura; his works in the special effects and make-up department making him a very visual storyteller and it is a skill that he has certainly utilized to the film’s benefit. Except for a few dated CGI effects, the rest of the film’s special effects are delightful watch in all their gruesomeness. The hectic editing and man-machine hybrids bring to mind, the works of many of the previously mentioned filmmakers of the genre, but Nishimura executes everything in his own personal style that will leave a lasting impact on its viewers.

Anatomia Extinction would eventually evolve into Tokyo Gore Police in 2008. While the film expands on the ideas introduced in Anatomia, still featuring the mysterious engineers and their morbid mutating powers, it’s too far removed from the cyberpunk genre to be counted as part of it. The focus is much more on gory action and Nishimura certainly rejoices in the almost endless possibilities for most outlandish body horror. The film definitely falls more on the side of splatterpunk rather than cyberpunk, but it’s an interesting watch as an extension of Anatomia and also a very decent example of Nishimura’s extraordinary special effects talents.

While a part of a larger cinematic movement, Japanese cyberpunk with is one-of-a-kind take on things, is almost a genre on its own right. From the rich and multifaceted animations to the uniquely dark and grimy films, it offers an outlook that is hard to find comparison for in the western cinema. Film listed here are just a tip of the iceberg. For more cyberpunk madness, please refer to the list below:

Further viewing:

-Electric Dragon 80.000 V (2001)

-Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004)

-Neo Tokyo (Meikyû monogatari, 1987)

-Guinea Pig: Android of Notre-dame (The guinea pig 2: Nôtoru Damu no andoroido, 1989)

-The Machine Girl (Kataude mashin gâru, 2008)

-Meatball Machine (2005)

-Metropolis (Metoroporisu, 2001)

-Serial Experiments Lain (1998)

-Ergo Proxy (2006)

-Psycho Pass (2012-2014)

-Bubblegum Crisis (Baburugamu kuraishisu, 1987)

Sources:

Tom Mes. “Sogo Ishii”. From Midnight Eye, Visions of Japanese Cinema, June 15, 2015, http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/sogo-ishii-2/

Mark Player. “Post-Human Nightmares – The World of Japanese Cyberpunk Cinema”. From Midnight Eye, Visions of Japanese Cinema, May 13, 2011, http://www.midnighteye.com/features/post-human-nightmares-the-world-of-japanese-cyberpunk-cinema/

Jasper Sharp. “Where to begin With Japanese Cyberpunk”. From BFI, April 1, 2019, https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/where-begin-japanese-cyberpunk

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews