From William Butler Yeats to Freddy Krueger and Beyond: An Interview with a True Cinema Maverick, Director Jack Sholder

From William Butler Yeats to Freddy Krueger and Beyond: An Interview with a True Cinema Maverick, Director Jack Sholder

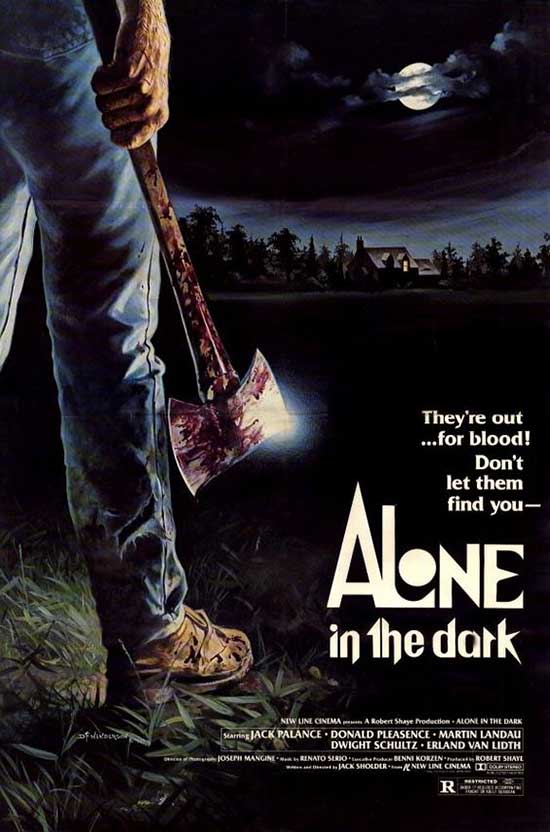

One of my very first experiences of quaking in my boots (er, sneakers really) at a horror feature in the theaters came in 1982 as a completely sponge-like, impressionable 15-year-old was accompanied by his dad to the local second-run house to see the wickedly funny slasher-yet-not chiller Alone in the Dark. For the next few days after, between the night terror bouts it unleashed, I became enthralled with the notion that one could laugh and scream in horror all within the same celluloid runtime! I just had to find out who the director of this film that impacted me so was. It turned out that Jack Sholder is anything but the simple horror or B-helmer. In fact, trying to shoehorn him into any category would be both inaccurate and impossible to do in a sense. This is someone who began his career trying to turn a verse play by Yeats set in 15th-Century Ireland into a film and went on to oversee one of the misadventures of Elm Street’s favorite blade-clawed denizen Freddy Krueger, after all? Simply put, I had to know more about him. Fast-forwarding years later, and thanks to social media, I was finally able to make contact with the gentleman who helped set my movie passions on a course down the shuddery road. Here is my interview, via email, with Mr. Jack Sholder:

Kevin: Growing up in the Wynnefield section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and playing the trumpet in school orchestras, where did your interest in filmmaking sprout from?

Jack Sholder: In high school my main interests were music and literature. When I decided not to pursue music as a career, after a brief detour into engineering I decided I wanted to be a writer, mainly poetry, with the idea that I’d support myself teaching at a university. At some point, with the help of drugs, I decided that words were meaningless which put a damper on writing. My girlfriend at the time was really into film, and I thought this would be a cool thing to do and starting watching every movie I could.

Kevin: Your first foray into making pictures was in 1973 with the short The Garden Party, based on Katherine Mansfield’s celebrated short story. An interesting treatise on dealing with tragedy and class prejudice that was required reading for me in my high school English Literature class. This also served as your initial screenwriting effort it seems. What is it about this work that drew you to it and can you discuss any trials and tribulations behind the project?

Jack Sholder: Actually, after first doing a 2 minute short in college, I decided to adapt At The Hawk’s Well a William Butler Yeats verse play set in 15th century Ireland, into a 20 minute film, definitely one of the worst ideas for a movie anyone has ever had. I did another short, Diary, about of young man who can only relate to the world through his camera, and while living in NYC and working as an editor, wrote and directed a short, Cats & Dogs, about a failed relationship that did the festival circuit. Paul Gurian, who produced it, was able to raise money to make another bigger short. The Garden Party really appealed to me since it was understated and had a wonderful epiphany at the end when the young girl realizes there is more to live that she had imagined. It also dealt with class and social commentary that I seems to go through most of my films.

Kevin: Regarding the years between The Garden Party and your first directorial feature effort, 1982’s Alone in the Dark, you have been quoted as saying “when 25 came and passed and I hadn’t made Citizen Kane yet, I was getting worried.” Was this a period of some career re-evaluation or re-assessment? Was there something that kept you persevering?

J.S.: I always thought, for some reason, that I would direct a feature which is a not very realistic goal. By my early thirties, as I was achieving success as a film editor, I began to wonder if it would ever happen. The Garden Party won a bunch of awards and played on PBS, so people knew I had some talent. I’d also written scripts that had gotten good notice. But I never pursued directing with the full intensity I felt I should have, and there didn’t seem to be that many opportunities in NYC. I’d had a long association with New Line Cinema and Bob Shaye, so when Bob told me they wanted to expand beyond distribution, and if they could make a low budget horror film they could clean up – this was in 1980 when Friday the 13th, Halloween, etc were raking in the bucks – I came up with an idea that eventually became Alone in the Dark. They paid me to write the script and said if they could raise the money they’d pay me to direct it. A year and a half later, we actually made it.

Kevin: In researching your career, I found that we share a common interest in the films of Jean Renoir. My first exposure came as a result of my father’s interest in the auteur and my getting to watch

La Grande Illusion from 1937. A poetic dissertation on class relationships among POWs during World War I. You’ve quoted in other interviews about having Renoir as your film-making influence. What is it that draws you to him and how has it impacted your own methods in making movies?

J.S.: I’ve always been drawn to French cinema. There is a humanism and richness of character that runs from Renoir through Marcel Carné (Children of Paradise – an absolute masterpiece) to Bresson and Truffaut and many others that I found enormously moving and inspiring. Renoir’s films especially engage in social commentary, with Grand Illusion and Rules of the Game, almost entirely about that which inspired me or at least spoke to me. I also admired their subtlety especially compared to most American films which seemed to frequently announce and explain too much. As someone who somehow fell into the horror/thriller genres as a way into directing features, the most important thing for me has always been character, to create ones that in some way mirror real life.

Kevin: Alone in the Dark presented rather a difficult task for you in that it is, on the surface at least, a slasher film. Yet, beneath that, it is anything but. In fact, it is a character story with some blood. You’ve expressed before a disdain for the slasher film and putting characters through humiliation, pain etc. Was there a conscious effort on your part hre to move away from the stock butcher knife psycho themes?

J.S.: Some directors like Wes express themselves through the horror genre. I’ve tried to express myself in spite of it. Which isn’t to say I don’t enjoy horror films when they’re done well. And I’ve had lots of fun making them since they appeal to the twisted ironist in my personality. Which also explains why Alone In The Dark, like most of my other films, has so much dark humor. It’s just that so many genre films are poorly made and have nothing going for them but the desire to disgust or shock which is pretty easy to do. Alone In The Dark is really satire masquerading as a slasher film. It’s about what it means to be “normal” and how it all breaks down at the slightest provocation. To quote Frans de Waal, human morality is “a cultural overlay, a thin veneer hiding an otherwise selfish and brutish nature.” And the corollary is also true, which is that what is deemed aberrant often is most profound as has often been the case with new ideas and new art. As Emily Dickenson wrote, “Much Madness is divinest Sense… Much Sense – the starkest Madness – ’Tis the Majority In this, as all, prevail – Assent – and you are sane –

J.S.: Some directors like Wes express themselves through the horror genre. I’ve tried to express myself in spite of it. Which isn’t to say I don’t enjoy horror films when they’re done well. And I’ve had lots of fun making them since they appeal to the twisted ironist in my personality. Which also explains why Alone In The Dark, like most of my other films, has so much dark humor. It’s just that so many genre films are poorly made and have nothing going for them but the desire to disgust or shock which is pretty easy to do. Alone In The Dark is really satire masquerading as a slasher film. It’s about what it means to be “normal” and how it all breaks down at the slightest provocation. To quote Frans de Waal, human morality is “a cultural overlay, a thin veneer hiding an otherwise selfish and brutish nature.” And the corollary is also true, which is that what is deemed aberrant often is most profound as has often been the case with new ideas and new art. As Emily Dickenson wrote, “Much Madness is divinest Sense… Much Sense – the starkest Madness – ’Tis the Majority In this, as all, prevail – Assent – and you are sane –

Demur – you’re straightway dangerous – And handled with a Chain –“

Kevin: Working with a cast like Jack Palance, Martin Landau and Donald Pleasence, all veterans of this type of material, would seem the ideal treat for someone making their debut in this genre. What was it like working with these men?

J.S.: It was intimidating, at least at first. Donald was the first one I shot with, and I was in awe of him as a truly great actor. But he was very professional, and when I gave him some direction, he actually did what I asked which was encouraging. Directing him and other wonderful actors I’ve been lucky to work with is like being given the keys to a Ferrari; touch the wheel and the car reacts perfectly. Landau was extremely warm and was easy to work with. He subsequently became a mentor of mine and I cast him in By Dawns Early Light and 12:01. Palance was intimidating, but he was fair. He was wonderful in the film, and I learned a lot from working with him.

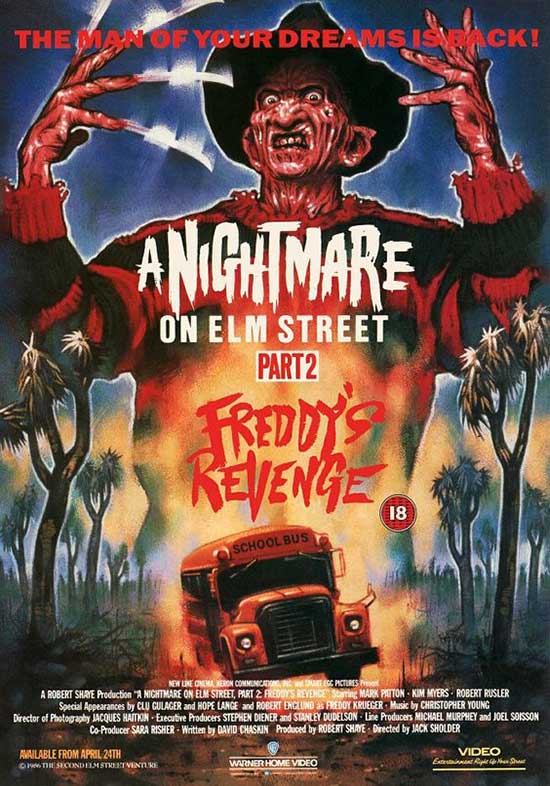

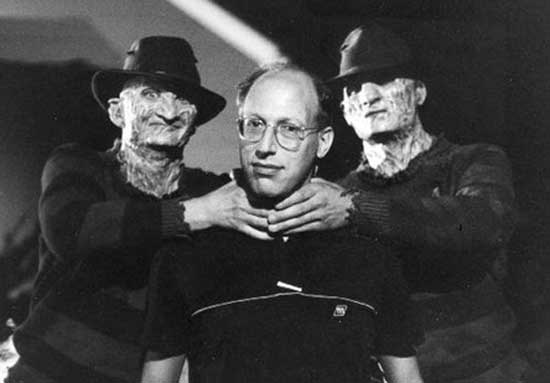

Kevin: I read some intriguing quotes from you regarding helming the first sequel to Wes Craven’s runaway smash horror hit from 1984, A Nightmare on Elm Street. You said were terrified when assigned to do the follow-up the next year, A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge, not because of the material but about stepping into the shoes of Craven as a relative newbie. Can you expound on this and was this a learning experience for you?

Jack Sholder: I was not intimidated at all since I felt confident of my filmmaking abilities and wasn’t that impressed with the original. What was intimidating was taking over a film 6 weeks before shooting that had with hundreds of effects that I had no idea how to do, many locations to find and actors to cast, and somehow to find the time to figure out how I was going to shoot the film, scene by scene. It felt impossible to get it all done in that time frame, and frankly I was scared. But somehow you manage, and when I walked onto the set on Day 1 fully prepared if exhausted, all the anxiety went away and adrenaline took over.

Kevin: I can’t let the subject of Freddy’s Revenge go without asking about the pool house scene and why it caused such a laughing streak for you that you let an assistant direct it? Please, please explain further if you can! LOL

J.S.: The plan was to start the make out scene with the part where the huge tongue comes out of Jesse’s mouth since that would take a long time to prep, then remove the prosthetic tongue and shoot the rest of the scene. The previous effect that Mark Shostrom’s team did kept us waiting for 3 hours. I told Shostrom, next time you wait on us, not us on you. So he got the tongue attached to Mark Patton’s mouth early, and the 1st unit was running late. During a break the asst director said Mark was sitting in his trailer very uncomfortable, couldn’t speak or eat or drink, and I should stop by to say I was sorry and we’d get to him soon. So I walk into his trailer and there is a ten inch green tongue with warts on it sticking out of Mark’s mouth and I burst out laughing – it had been a very long night and I was a little punchy. Mark couldn’t talk, so he wrote on a pad IT’S NOT FUNNY! Which of course it was. I left quickly. We set up the shot with a stand-in and brought Mark in at the last moment. When I saw him I struggled not to laugh and figured if Mark saw that he’d get pissed and walk off – not that he would have done that since he was very professional – but at least he’d have more trouble with the scene that he needed and he’d feel bad. So I stood outside the pool house, told the asst director what to tell Mark, and watched the scene thru a crack in the door. I didn’t even call Action and Cut because I was afraid if I opened my mouth I’d burst out laughing and used hand signals instead. Once the tongue was off I went back in and finished directing the scene.

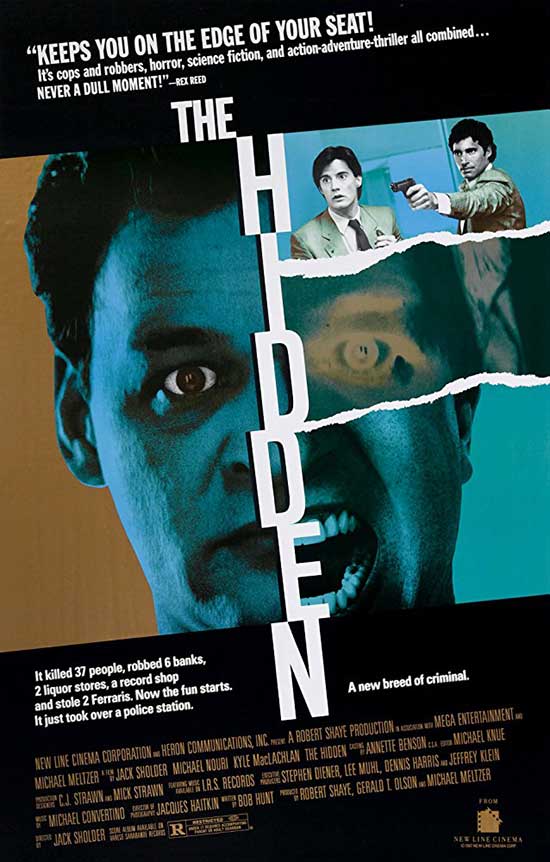

Kevin: Your next venture, 1987’s The Hidden, proved to be one of your most original and innovative pieces. Not sure if there are many cop drama/alien parasite mash-ups out there. Certainly none that work so seamlessly. And likely none having a cast with as diverse of acting styles as this. Kyle Maclachlan and Michael Nouri aren’t the first pair that comes to mind for the ideal cop buddy team? Were there any issues doing this picture? I understand you were further influenced by a master of gritty crime milieu’s, Sidney Lumet, on several scenes in the film.

J.S.: The script by Jim Kouf was terrific – funny, smart, original. I also thought it dealt with the bigger theme of what it means to be human. And I saw it as a cop thriller, which I’d always wanted to, but with aliens. It’s no secret that Michael Nouri and I had a very poor working relationship, and whenever I had to do a scene with him – and he was in most of the scenes – he always kept me off balance and feeling as if I was the dumbest guy on the set, which I’ve learned is how many directors sometimes feel. Somehow – and maybe even because of it – I managed to make a good film. Probably because I had such a strong connection to the material. No doubt Jacques Haitkin, who had shot Elm St II for me and was very experienced, was an enormous help. And Kyle was wonderful to work with. It’s funny – I thought Nouri was stealing the film from Kyle since he had most of the lines and took up most of the air. But watching The Hidden, it is clearly Kyle’s film. Which proves that in film the reaction is often far more interesting than the action or the line of dialogue. I should mention that Nouri and I reconnected by chance some ten years later and patched things up.

Kevin: Staying with the cop buddy formula, your 1989 Renegades had an Odd Couple-ish teaming of lead characters that had to have been a first on numerous levels: a street-wise cop and a Lakota Indian? You also get an opportunity to film in your old stomping grounds in Philly as well as on some lush locations in Ontario, Canada. What was this whole experience like? Lou Diamond Phillips and Kiefer Sutherland both have been known to be a bit of pranksters on film sets. Did everything seem pretty loose or was it mostly business?

J.S.: Lou was charming. Kiefer could be a bit dark sometimes, but both were very serious about their work and totally professional.. Kiefer’s wardrobe was based on late summer which is when we started shooting. By the time we were finishing it was really cold in Toronto, especially at night. I’m standing out there totally bundled up and still freezing, and Kiefer would be doing his scenes in a tee shirt. A real trooper! No pranks on the set, but Lou finished up his final scene before lunch and had tee shirts made up for everyone on the crew. There were big hugs and goodbyes since everyone loved him.

Then Lou got in his car and was driven off. He went about 50 feet, then circled back, rolled down his window, and mooned everyone, then drove off.

Kevin: You made a segue in the 90s to doing quite a bit of tv. I’ve read where some directors gravitated toward the medium because it offered greater freedoms in creativity and expression. You did do some incredible projects such as the political action thriller By Dawn’s Early Light (a gem that deserves all of the accolades it gets) and the smartly funny sci-fi/comedy 12:01 from 1993 (where you reunite with a favorite stalwart of mine, Martin Landau). Did you come to the small screen for more artistic flexibility or was it simply that tv offers were more prevalent than film?

J.S.: Renegades was released in the summer in the middle of Indiana Jones, Batman, Back to the Future 2, Lethal Weapon 2. Financially it got killed and the reviews weren’t great, and that put a damper on my studio feature career. HBO had offered me several projects that I had turned down. I was feeling pretty worried about the Renegades release when HBO sent over By Dawn’s. It was a terrific script and seemed like a very adult sort of movie with, while not a feature budget, a much better budget and schedule than a TV movie. So I did accepted and had a great time making it with a great cast that included Landau, James Earl Jones, Rip Torn, etc. 12:01 was again a terrific script, and it was New Line and would get a theatrical release everywhere but the U.S. By then I was getting more offers to do TV movies but not so many features, or at least not good ones. I seemed to get the more offbeat MOWs like Generation X (junior x-men) and Dark eflections (evil clones), and I got longer shooting schedules than the usual TV movies. The nice thing about MOWs was that, unlike features, as long as I made my days and more or less shot the script, they left me alone. And because there was less time to shoot, there was less time for discussion and so, other than the time pressure and smaller budgets, I got to make the movies pretty much the way I wanted.

J.S.: Renegades was released in the summer in the middle of Indiana Jones, Batman, Back to the Future 2, Lethal Weapon 2. Financially it got killed and the reviews weren’t great, and that put a damper on my studio feature career. HBO had offered me several projects that I had turned down. I was feeling pretty worried about the Renegades release when HBO sent over By Dawn’s. It was a terrific script and seemed like a very adult sort of movie with, while not a feature budget, a much better budget and schedule than a TV movie. So I did accepted and had a great time making it with a great cast that included Landau, James Earl Jones, Rip Torn, etc. 12:01 was again a terrific script, and it was New Line and would get a theatrical release everywhere but the U.S. By then I was getting more offers to do TV movies but not so many features, or at least not good ones. I seemed to get the more offbeat MOWs like Generation X (junior x-men) and Dark eflections (evil clones), and I got longer shooting schedules than the usual TV movies. The nice thing about MOWs was that, unlike features, as long as I made my days and more or less shot the script, they left me alone. And because there was less time to shoot, there was less time for discussion and so, other than the time pressure and smaller budgets, I got to make the movies pretty much the way I wanted.

Kevin: I’m also something of a fan of the actor Andrew Divoff and the Wishmaster series. As with the Elm Street films, you were called upon to direct the first sequel here, 1999’s Wishmaster 2: Evil Never Dies. Can you verify, if true, how that method-acting maestro Divoff manages to do 2-3 minute scenes with his eyes never blinking? I can’t do 2-3 seconds much of the time! This film also afforded you the opportunity to work again with your Freddy’s Revenge Cinematographer Jacques Haitkin and character actor extraordinaire Robert LaSardo from Renegades. Can you touch on working with those two and your relationships with them?

J.S.: I was offered the original Wishmaster and turned it down since I didn’t care for the script. When they asked me to write and direct the sequel I hesitated, but quite honestly I needed a movie to do. And I thought the concept of “be careful what you wish for” was a good subject, given my taste for irony. What are situations where people especially wish for things? Well, Vegas: “I wish I could win…” Prison: “I wish I could get out…” And how could those expectations go horribly wrong, as expectations sometimes do. Working with Andrew was a blast. I had actually worked with him on By Dawn’s – he’s a brilliant guy who speaks fluent Russian and was the voice of the assistant to the Russian president. As for the blinking, he is a very disciplined and intense actor. Really more amazing was how he could act in that stifling makeup and with these horrible contacts in his eyes. By the last week of the shoot his eyes were scratched from the lenses and his skin messed up from the makeup and he was agony. We did everything we could to minimize the time he had the contacts in, but Andrew soldiered on, for the most part sucked it up, and it never affected his performance. I could not have handled what he had to go through. BTW, the DP was Carlos Gonzalez, not Jacques. As for Robert La Sardo, I love working with good character actors and like to use them again if I can. Guys like Steve Eastin, Glenn Morshower, and Danny Trejo and Lin Shaye before they became stars.

Kevin: As you’ve bore witness to the horror and fantasy genre, having worked in it and observed it from a distance, where do you see the genre heading in the next few years and do you like where it is at right now?

J.S.: There are always good ones and bad ones. The good ones are always about more than just the horror. Think Get Out, It, the Babadook, Let The Right One In, anything by Del Toro or David Cronenberg. Etc. Or to go back further, Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, Rosemary’s Baby, Forbidden Planet. And some are just fun being scary or pushing the envelope like the Spanish film Rec or the French gorefest Inside. As for where the genre is going, all I can say is that I hope people keep making good films for the big screen and audiences keep going to see them in movie theatres which is what they are made for.

Kevin: I see from research that you are a teacher and Director of Motion Pictures and Television at Western Carolina University these days. What prompted you to go into the educational side of the entertainment industry and Do you see the same drive for creativity and expression in your students that were in yourself as a youth?

J.S.: I retired from the university this summer after 13 years. I was offered an opportunity to start a film production program from scratch, and while I still was directing it was getting more stressful to find the work. I’d never gone to film school or taught, so it was a challenge to figure out how to teach filmmaking and how to structure a four-year curriculum that would actually teach people what it was all about and prepare them for work in the industry. The one thing I did know was that the basis of everything needed to be storytelling since all the top people I’d worked with had a strong understanding of story, no matter what job they were doing. What was interesting for me was that, being self-taught, I worked out of instinct, and I learned by experience and, yes, by making mistakes. Now I had to think of why I did what I did in order to teach it and to develop rules, such as they are, that the students could use. I came to understand a lot about what I’d been doing for all those years. Interesting that when I have occasion to watch my films, I see that I pretty much adhered to those rules and, at least from a craft point of view, I did everything right.

Kevin: It is gratifying to see that you’ve not entirely left the business. IMDB notes that you are in pre-production as executive producer for something called Reenactment. Can you provide more details about this and when fans can expect to see it as well as what you have in store, project-wise, for the future?

J.S.: I am currently involved in a film loosely based on “Carmilla,” a 19th century vampire novel by Sheridan LeFanu about young female vampires. I’ve been working on the adaptation with Josh Russell and am very excited about how well it turned out. We’re currently putting the financing for Carmilla together, and with any luck I will shoot it this year. Please keep fingers crossed. Mine are.

Many thanks to Mr. Sholder for the willingness to take the time and answer the queries of an unabashed fan. Here’s to hoping he keeps affecting the impressionable youth enough as to create more fans, whether it be a creep-fest chiller (with tongue firmly lodged in cheek of course) or high octane action flick and continues doing things decidedly different.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews