SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“It has been several years since the disaster at the Delos resort (the events of Westworld), and Delos is ready to reopen, replacing Westworld with the new ‘Futureworld’ which is getting rave reviews. However, one of Delos’s most famous critics, reporter Chuck Browning, is still not convinced that Delos has cleaned up its act, especially after an informant with inside information about Delos is murdered. Chuck teams up with fellow reporter Tracy Ballard and goes to Delos to find out why his source was killed. What they discover is beyond any of their imaginations.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Some of the best known films from 1973 to 1983, such as Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977), Star Wars IV A New Hope (1977) and Flash Gordon (1980), have already been discussed here on Horror News, and they were a fairly cheerful bunch on the whole. But science fiction films during that decade were full of forebodings as well. One of the main themes has been the fear that technology might run wild, whether biologically – as in The Boys From Brazil (1978) or Android (1982) – or electronically – as in Colossus The Forbin Project (1970) or Demon Seed (1977). Another oft-asked question was, what will life be like after Armageddon? Will it look like Zardoz (1972) or Mad Max (1979)? At least we can amuse ourselves with weird lethal aircraft such as Firefox (1982) or Blue Thunder (1983), or we could experiment with the strange powers of the mind as seen in Altered States (1980) or Brainstorm (1983). We might need to cope with enigmatic alien creatures as we did in Solaris (1972) or Strange Invaders (1983), while some alien visitors will be quite innocuous, perched in front of their televisions like The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976). If all else fails, we can always go out and have adventures at the other end of the galaxy as seen in Star Trek The Motion Picture (1979) or The Black Hole (1979).

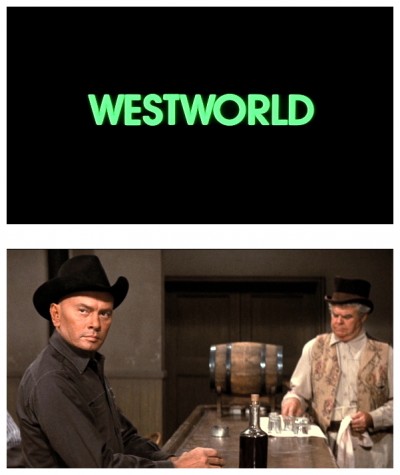

Life may be dangerous in the future, but it certainly won’t be dull. Perhaps the future will see us trying to kill ourselves playing lunatic sports like Rollerball (1975) or Death Race 2000 (1975)? A much better film about surrogate violence is Westworld (1973), the feature-film directorial debut of novelist Michael Crichton, who also wrote the screenplay. Westworld is part of a Disneyland-styled theme park of the future called Delos, along with Medievalworld and Romanworld. But animatronic technology has come a long way, and these three areas offer surprisingly convincing simulacra of the real thing, though many of the ‘people’ who live in the old-time Wild West township are actually robot duplicates, as are the horses, snakes and other animals. They’re cleverly made though, and visitors who stay at the local inn can make love to robot whores and have shoot-outs with robot gunmen in the secure knowledge that in both cases they will come out on top.

Life may be dangerous in the future, but it certainly won’t be dull. Perhaps the future will see us trying to kill ourselves playing lunatic sports like Rollerball (1975) or Death Race 2000 (1975)? A much better film about surrogate violence is Westworld (1973), the feature-film directorial debut of novelist Michael Crichton, who also wrote the screenplay. Westworld is part of a Disneyland-styled theme park of the future called Delos, along with Medievalworld and Romanworld. But animatronic technology has come a long way, and these three areas offer surprisingly convincing simulacra of the real thing, though many of the ‘people’ who live in the old-time Wild West township are actually robot duplicates, as are the horses, snakes and other animals. They’re cleverly made though, and visitors who stay at the local inn can make love to robot whores and have shoot-outs with robot gunmen in the secure knowledge that in both cases they will come out on top.

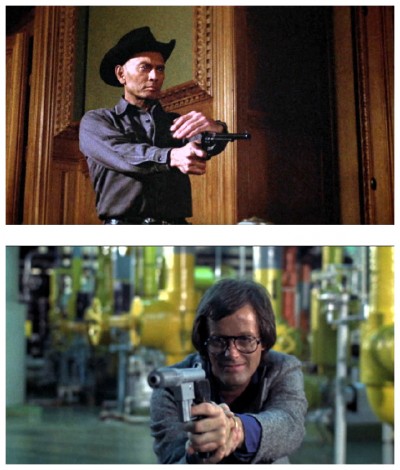

The film begins with the arrival of two male visitors (Richard Benjamin and James Brolin) who both enjoy themselves on the first day by out-shooting the local gunslinger (Yul Brynner) and sleeping with the robot saloon girls (Majel Barrett-Roddenberry and Anne Randall). The fantasies of machismo being lived out by the tourists (mostly men, as woman seem to prefer Romanworld) turn into nightmares. Things go drastically wrong the following day when the robot gunslinger actually outdraws one of the men (Brolin) and shoots him dead, leaving his companion in a extremely frightening position. Up until this point, Westworld seems as if it’s going to do something out of the ordinary. The Wild West park isn’t based on the real Old West but Hollywood’s recreation of it, a point emphasised by the fact that Brynner wears the same costume he wore in The Magnificent Seven (1960).

The film begins with the arrival of two male visitors (Richard Benjamin and James Brolin) who both enjoy themselves on the first day by out-shooting the local gunslinger (Yul Brynner) and sleeping with the robot saloon girls (Majel Barrett-Roddenberry and Anne Randall). The fantasies of machismo being lived out by the tourists (mostly men, as woman seem to prefer Romanworld) turn into nightmares. Things go drastically wrong the following day when the robot gunslinger actually outdraws one of the men (Brolin) and shoots him dead, leaving his companion in a extremely frightening position. Up until this point, Westworld seems as if it’s going to do something out of the ordinary. The Wild West park isn’t based on the real Old West but Hollywood’s recreation of it, a point emphasised by the fact that Brynner wears the same costume he wore in The Magnificent Seven (1960).

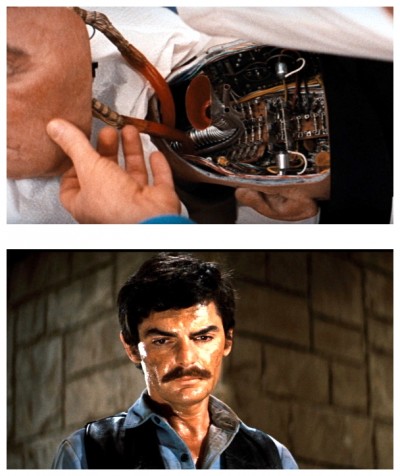

The lethal implacable Brynner robot seems to be indestructible as he stalks the remaining tourist (Benjamin) through the corpse-littered streets, not even pausing when his face is destroyed by acid – a memorable image which abruptly reminds us that he is indeed a robot – revealing the whirling cogs and flickering circuits beneath. The film appears to be about a man who discovers that his machismo fantasies (created and nourished by films and television) are somewhat redundant in the face of grim reality. But from this point on Westworld becomes the sort of film that visitors to the park would like to pretend they’re a part of, a film in which the hero overcomes all odds by blasting his way to victory. Though entertaining, the film is ultimately a disappointment because it fails to deliver what it promises. Furthermore, the screenplay is rather vague on the reasons behind the robot revolt.

The lethal implacable Brynner robot seems to be indestructible as he stalks the remaining tourist (Benjamin) through the corpse-littered streets, not even pausing when his face is destroyed by acid – a memorable image which abruptly reminds us that he is indeed a robot – revealing the whirling cogs and flickering circuits beneath. The film appears to be about a man who discovers that his machismo fantasies (created and nourished by films and television) are somewhat redundant in the face of grim reality. But from this point on Westworld becomes the sort of film that visitors to the park would like to pretend they’re a part of, a film in which the hero overcomes all odds by blasting his way to victory. Though entertaining, the film is ultimately a disappointment because it fails to deliver what it promises. Furthermore, the screenplay is rather vague on the reasons behind the robot revolt.

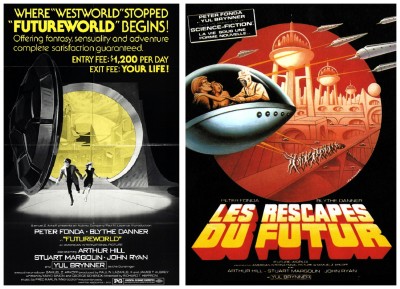

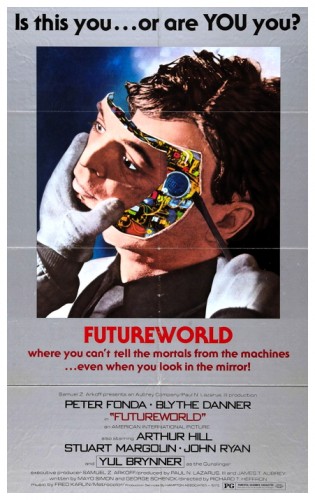

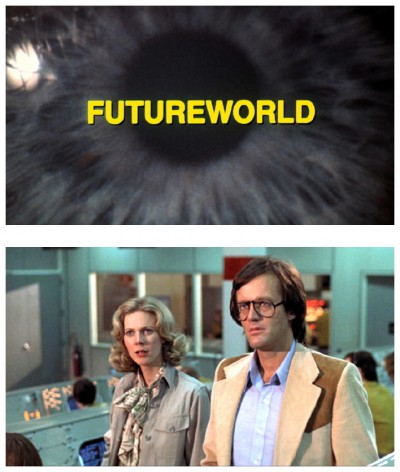

As a film about the absurdity of male fantasies, Westworld is excellent but, as a film about the revolt of the technological world against the humans who created it, it’s rather predictable but still good fun. This is more than can be said for its disappointing sequel, Futureworld (1976), which is set in another newly-built section of the theme park complex. There are some entertaining sequences, mostly derivative of the first film, but it is a thorough mess. The film was developed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the studio who had produced Westworld, except MGM decided to make Logan’s Run (1976) instead and shelved Futureworld, and it was picked up cheap by American International Pictures. The story takes place two years after Westworld, and the Delos corporation have reopened the park after spending more than a billion dollars in safety improvements, which is why the prices have inflated from US$1000 a day in the first film to US$1200. Journalists Chuck Browning (Peter Fonda) and Tracy Ballard (Blythe Danner) are invited to review the park, and Browning arranges to meet with a Delos whistleblower but, during the meeting, the tipster is shot in the back and dies after giving Browning an envelope.

As a film about the absurdity of male fantasies, Westworld is excellent but, as a film about the revolt of the technological world against the humans who created it, it’s rather predictable but still good fun. This is more than can be said for its disappointing sequel, Futureworld (1976), which is set in another newly-built section of the theme park complex. There are some entertaining sequences, mostly derivative of the first film, but it is a thorough mess. The film was developed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the studio who had produced Westworld, except MGM decided to make Logan’s Run (1976) instead and shelved Futureworld, and it was picked up cheap by American International Pictures. The story takes place two years after Westworld, and the Delos corporation have reopened the park after spending more than a billion dollars in safety improvements, which is why the prices have inflated from US$1000 a day in the first film to US$1200. Journalists Chuck Browning (Peter Fonda) and Tracy Ballard (Blythe Danner) are invited to review the park, and Browning arranges to meet with a Delos whistleblower but, during the meeting, the tipster is shot in the back and dies after giving Browning an envelope.

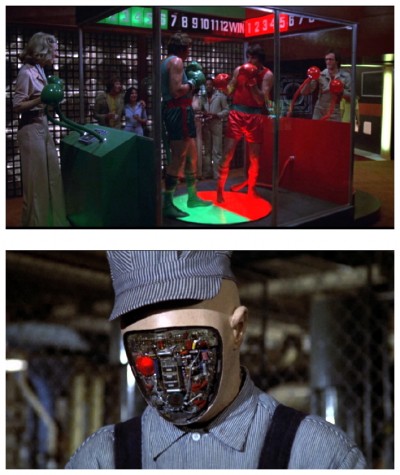

Entering the resort, guests have a choice of theme parks: Medievalworld, Romanworld and Futureworld (Westworld has been closed down). The journalists choose Futureworld, which simulates an orbiting space station. Just as in the first film, robots are available for all sorts of amusements, from sex to boxing, where the humans remote-control robot fighters like replicant Rock’em Sock’em Robots. Their host, Doctor Duffy (Arthur Hill), shows them the marvels of Delos and the control centre which is staffed entirely by robots, but he assures them that all the problems have been fixed. That night the journalists are drugged and medical tests are conducted so Delos can make duplicates, and we also see a visiting Russian general and a Japanese politician going through the same procedure. Later Ballard wakes in fright, thinking it was all a dream. The journalists sneak out to explore the underground areas, triggering a security device which generates three android samurai. A mechanic named Harry (Stuart Margolin) saves them from the samurai, and takes them back to his quarters to meet his only friend, a faceless robot named Clark (James O’Connor).

Entering the resort, guests have a choice of theme parks: Medievalworld, Romanworld and Futureworld (Westworld has been closed down). The journalists choose Futureworld, which simulates an orbiting space station. Just as in the first film, robots are available for all sorts of amusements, from sex to boxing, where the humans remote-control robot fighters like replicant Rock’em Sock’em Robots. Their host, Doctor Duffy (Arthur Hill), shows them the marvels of Delos and the control centre which is staffed entirely by robots, but he assures them that all the problems have been fixed. That night the journalists are drugged and medical tests are conducted so Delos can make duplicates, and we also see a visiting Russian general and a Japanese politician going through the same procedure. Later Ballard wakes in fright, thinking it was all a dream. The journalists sneak out to explore the underground areas, triggering a security device which generates three android samurai. A mechanic named Harry (Stuart Margolin) saves them from the samurai, and takes them back to his quarters to meet his only friend, a faceless robot named Clark (James O’Connor).

Harry takes them to a locked door that he has never been able to open, although robots routinely enter. Inside they find duplicates of themselves as well as the Russian and Japanese leaders being programmed with subliminal messages, including instructions to kill their originals. Browning explains that the whistleblower’s envelope was full of clippings about leaders from around the world, and came to the unlikely conclusion that Delos must be duplicating the rich and powerful, and duplicating the journalists would ensure favourable coverage. Browning attacks Duffy, but is easily overpowered with unnatural strength. Ballard shoots the doctor twice, then Duffy’s face is peeled off revealing he’s an android too. Ballard and Browning are then chased by their own duplicates and, eventually, one of each pair is killed, though which one is left unclear until they kiss. As they leave the resort, Doctor Schneider (John Ryan) checks to confirm they are the duplicates but, just as they reach the exit, Ballard’s badly injured duplicate appears and Schneider realises too late that the journalists have succeeded in escaping.

Harry takes them to a locked door that he has never been able to open, although robots routinely enter. Inside they find duplicates of themselves as well as the Russian and Japanese leaders being programmed with subliminal messages, including instructions to kill their originals. Browning explains that the whistleblower’s envelope was full of clippings about leaders from around the world, and came to the unlikely conclusion that Delos must be duplicating the rich and powerful, and duplicating the journalists would ensure favourable coverage. Browning attacks Duffy, but is easily overpowered with unnatural strength. Ballard shoots the doctor twice, then Duffy’s face is peeled off revealing he’s an android too. Ballard and Browning are then chased by their own duplicates and, eventually, one of each pair is killed, though which one is left unclear until they kiss. As they leave the resort, Doctor Schneider (John Ryan) checks to confirm they are the duplicates but, just as they reach the exit, Ballard’s badly injured duplicate appears and Schneider realises too late that the journalists have succeeded in escaping.

Although the industry newspaper Variety said Futureworld was a strong sequel, most viewers sided with critics like Richard Eder, who quoted Blythe Danner‘s line, “This is about as exciting as a visit to the waterworks.” He dismissed the film as utterly predictable and totally devoid of dramatic tension: “About as much fun as running barefoot on Astroturf. Danner and Fonda have absolutely nothing to do – starring in Futureworld must be the actor’s equivalent of going on welfare.” Audiences were also disappointed by Yul Brynner‘s minor cameo appearance as the gunslinger in a tacked-on dream sequence, his final film role before sadly succumbing to lung cancer. In fact, the most interesting thing about Futureworld is that it was the first major motion picture to use 3-D computer-generated imagery, for an animated hand and face. The animated left hand actually belongs to Edwin Catmull, future president of Pixar, whose experimental short film A Computer Animated Hand (1971) was utilised.

Although the industry newspaper Variety said Futureworld was a strong sequel, most viewers sided with critics like Richard Eder, who quoted Blythe Danner‘s line, “This is about as exciting as a visit to the waterworks.” He dismissed the film as utterly predictable and totally devoid of dramatic tension: “About as much fun as running barefoot on Astroturf. Danner and Fonda have absolutely nothing to do – starring in Futureworld must be the actor’s equivalent of going on welfare.” Audiences were also disappointed by Yul Brynner‘s minor cameo appearance as the gunslinger in a tacked-on dream sequence, his final film role before sadly succumbing to lung cancer. In fact, the most interesting thing about Futureworld is that it was the first major motion picture to use 3-D computer-generated imagery, for an animated hand and face. The animated left hand actually belongs to Edwin Catmull, future president of Pixar, whose experimental short film A Computer Animated Hand (1971) was utilised.

But wait! The Westworld saga doesn’t end there, oh no! Beyond Westworld (1980) was an extremely short-lived television series that continues the stories established in the two films. How short-lived? Five episodes. It’s no surprise considering the singular story-line: Delos Security Chief John Moore (Jim McMullan) attempts to stop to the evil scientist Simon Quaid (James Wainwright), who plans to use Delos robots to take over the world. The show was considered so bad it was brutally axed after only three episodes with another two in the can, then later that year the series was actually nominated for a couple of Emmy Awards for Makeup and Art Direction. I’ll allow you to mull over the questionable judgment of American television executives for the next seven days, and politely invite you to meet me here next week on Horror News when I have another opportunity to inflict a pain beyond pain, an agony so intense it shocks the mind into instant mashed potato! Toodles!

But wait! The Westworld saga doesn’t end there, oh no! Beyond Westworld (1980) was an extremely short-lived television series that continues the stories established in the two films. How short-lived? Five episodes. It’s no surprise considering the singular story-line: Delos Security Chief John Moore (Jim McMullan) attempts to stop to the evil scientist Simon Quaid (James Wainwright), who plans to use Delos robots to take over the world. The show was considered so bad it was brutally axed after only three episodes with another two in the can, then later that year the series was actually nominated for a couple of Emmy Awards for Makeup and Art Direction. I’ll allow you to mull over the questionable judgment of American television executives for the next seven days, and politely invite you to meet me here next week on Horror News when I have another opportunity to inflict a pain beyond pain, an agony so intense it shocks the mind into instant mashed potato! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews