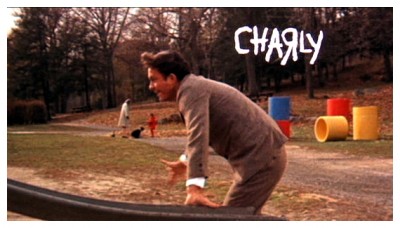

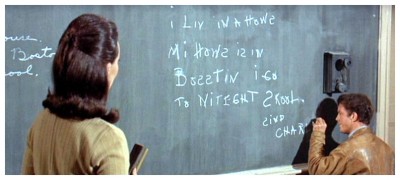

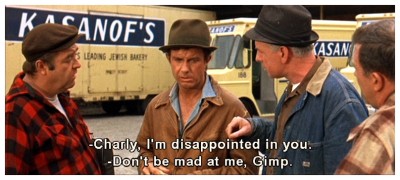

“Charly is an adult male with a cognitive disability struggling to survive in the modern world. His frequent attempts at learning, reading and writing prove difficult. His teacher, Miss Kinian, takes Charly to the clinic where he is observed by doctors who have Charly ‘race’ a mouse, Algernon. Algernon is usually the winner thanks to an experiment that greatly raised his intelligence. This experiment is given to Charly, who at first does not seem affected. However, he becomes more logically advanced, eventually becoming a pure genius. Emotional and intra-personal consequences are involved when Charly learns the truth of the experiment, and struggles with whether or not the procedure was a good idea.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

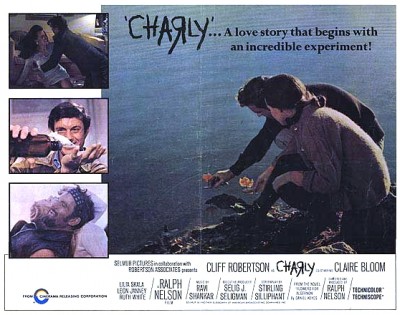

The best science fiction films of the sixties – apart from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – were the quiet ones not set in the future or in space, like Charly (1968) directed efficiently but without charm by Ralph Nelson, scripted by Stirling Siliphant and based on the award-winning novella (which was later expanded into a full novel) by Daniel Keyes entitled Flowers For Algernon. The story of the film follows the original quite closely, and tells of a mentally-retarded floor-sweeper who becomes the subject of a scientific experiment designed to increase intelligence, an experiment that has already been carried out on a mouse named Algernon, apparently successfully.

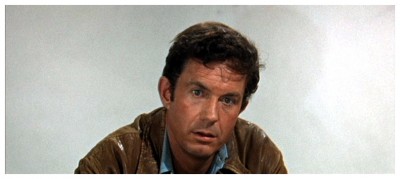

Most actors would jump at the chance to play a character who, within the time-span of one film, ranges from a subnormal thirty-year-old to a super-genius and then back again to subnormal. Cliff Robertson did more than jump at the chance. He formed his own production company and, after various setbacks, succeeded in obtaining the necessary finance to make the film. It was a gamble that paid off in more ways than one, and his performance as Charly won him an Oscar that year. Robertson’s best roles can be found in such films as PT-109 (1963), 633 Squadron (1964), The Honey Pot (1967), Too Late The Hero (1970), Obsession (1976), Class (1983), Brainstorm (1983), Escape From LA (1996) and Spider-Man (2002).

Most actors would jump at the chance to play a character who, within the time-span of one film, ranges from a subnormal thirty-year-old to a super-genius and then back again to subnormal. Cliff Robertson did more than jump at the chance. He formed his own production company and, after various setbacks, succeeded in obtaining the necessary finance to make the film. It was a gamble that paid off in more ways than one, and his performance as Charly won him an Oscar that year. Robertson’s best roles can be found in such films as PT-109 (1963), 633 Squadron (1964), The Honey Pot (1967), Too Late The Hero (1970), Obsession (1976), Class (1983), Brainstorm (1983), Escape From LA (1996) and Spider-Man (2002).

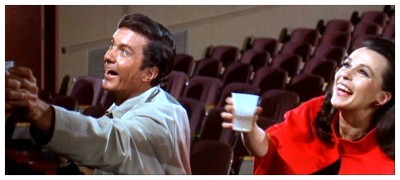

Cliff Robertson could also be found on the small-screen in Rod Brown Of The Rocket Rangers, The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone and Batman. When he’s not acting up a storm, Cliff relaxes by collecting vintage fighter aircraft, including a Messerschmitt BF-108, a Supermarine Spitfire, and several Tiger Moths, and was given the Good Will Aviation Award by the National Transportation Safety Association. As usual, he gives an intelligent and sensitive performance in Charly as a man with the mind of a child slowly coming to full adult life and knowledge, as well as falling in love with his doctor (Claire Bloom).

Cliff Robertson could also be found on the small-screen in Rod Brown Of The Rocket Rangers, The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone and Batman. When he’s not acting up a storm, Cliff relaxes by collecting vintage fighter aircraft, including a Messerschmitt BF-108, a Supermarine Spitfire, and several Tiger Moths, and was given the Good Will Aviation Award by the National Transportation Safety Association. As usual, he gives an intelligent and sensitive performance in Charly as a man with the mind of a child slowly coming to full adult life and knowledge, as well as falling in love with his doctor (Claire Bloom).

Apart from being an effective showcase of an actor’s talents, the film also retains some of the evocative pathos of the original story. The main interest of the story is that the operation turns out to be only a temporary success and Charly, now a genius, has to come face-to-face with the fact that all he has gained will be lost again. His moment of realisation is certainly touching and there is a horrible fascination in watching his IQ being slowly stripped away, but it may be because the original story was never quite as good as the claims made for it. Certainly, blown up for the big screen, its elements of sentimentality seem a little over-inflated, and are milked for all they’re worth.

Apart from being an effective showcase of an actor’s talents, the film also retains some of the evocative pathos of the original story. The main interest of the story is that the operation turns out to be only a temporary success and Charly, now a genius, has to come face-to-face with the fact that all he has gained will be lost again. His moment of realisation is certainly touching and there is a horrible fascination in watching his IQ being slowly stripped away, but it may be because the original story was never quite as good as the claims made for it. Certainly, blown up for the big screen, its elements of sentimentality seem a little over-inflated, and are milked for all they’re worth.

This mainly due to the rather wooden direction of Ralph Nelson, whose best work could be found on television. He served as Production Manager on The Twilight Zone and directed the acclaimed episode A World Of His Own. Not only did he direct both the television and film versions of Rod Serling‘s Requiem For A Heavyweight (1956 & 1962), he also directed the made-for-TV movie about the making of Requiem For A Heavyweight entitled The Man In The Funny Suit (1960). He then moved to the big screen with Lilies Of The Field (1963), Tick Tick Tick (1970), Soldier Blue (1970), The Wilby Conspiracy (1975) and Embryo (1976). He returned to television in the late seventies with a string of mediocre made-for-TV movies before passing away in 1987.

This mainly due to the rather wooden direction of Ralph Nelson, whose best work could be found on television. He served as Production Manager on The Twilight Zone and directed the acclaimed episode A World Of His Own. Not only did he direct both the television and film versions of Rod Serling‘s Requiem For A Heavyweight (1956 & 1962), he also directed the made-for-TV movie about the making of Requiem For A Heavyweight entitled The Man In The Funny Suit (1960). He then moved to the big screen with Lilies Of The Field (1963), Tick Tick Tick (1970), Soldier Blue (1970), The Wilby Conspiracy (1975) and Embryo (1976). He returned to television in the late seventies with a string of mediocre made-for-TV movies before passing away in 1987.

It’s certainly not the fault of the faithful screenplay by Stirling Silliphant, who is probably best known for adapting In The Heat Of The Night (1967) and writing a number of Irwin Allen blockbusters including The Poseidon Adventure (1972), The Towering Inferno (1974), The Swarm (1978) and When Time Ran Out (1980). In the case of The Towering Inferno, Silliphant was tasked with blending two entirely unrelated novels (The Tower by Richard Martin Stern and The Glass Inferno by Thomas Scortia) into a single screenplay. Silliphant is also remembered for his now-infamous bet with Hal Warren on whether Warren could make a successful horror film on a limited budget, which resulted in one of the worst films ever made, Manos The Hands Of Fate (1966).

It’s certainly not the fault of the faithful screenplay by Stirling Silliphant, who is probably best known for adapting In The Heat Of The Night (1967) and writing a number of Irwin Allen blockbusters including The Poseidon Adventure (1972), The Towering Inferno (1974), The Swarm (1978) and When Time Ran Out (1980). In the case of The Towering Inferno, Silliphant was tasked with blending two entirely unrelated novels (The Tower by Richard Martin Stern and The Glass Inferno by Thomas Scortia) into a single screenplay. Silliphant is also remembered for his now-infamous bet with Hal Warren on whether Warren could make a successful horror film on a limited budget, which resulted in one of the worst films ever made, Manos The Hands Of Fate (1966).

Charly is a self-conscious contemporary drama, and is probably the first ever to exploit mental retardation for the bittersweet romance of it. For all of its earnestness, the audience are forced into the vaguely unpleasant position of being voyeurs, congratulating ourselves for not being Charly as often as we feel a distant pity for him. But for all the easy manipulation of an audience’s ready sympathies, this very likable though rather stiff film does have something serious, if not profound, to say about human intelligence and emotion, and the way they’re linked. After decades in which science fiction films mostly meant monsters, Charly was a very definite step in the direction of relative maturity. It’s with this thought in mind I’ll politely ask you to please join me next week when I fish-out more celluloid slop from the wheelie-bin behind Fox Studios and force-feed it to you without a spoon, all in the name of art for…Horror News. Toodles!

Charly is a self-conscious contemporary drama, and is probably the first ever to exploit mental retardation for the bittersweet romance of it. For all of its earnestness, the audience are forced into the vaguely unpleasant position of being voyeurs, congratulating ourselves for not being Charly as often as we feel a distant pity for him. But for all the easy manipulation of an audience’s ready sympathies, this very likable though rather stiff film does have something serious, if not profound, to say about human intelligence and emotion, and the way they’re linked. After decades in which science fiction films mostly meant monsters, Charly was a very definite step in the direction of relative maturity. It’s with this thought in mind I’ll politely ask you to please join me next week when I fish-out more celluloid slop from the wheelie-bin behind Fox Studios and force-feed it to you without a spoon, all in the name of art for…Horror News. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

tory burch 店舗

The original novel, Flowers for Algernon, was deeply touching in an earned, honest emotional way. I think it’s primary theme is about loss… As we age what happened to Charlie happens to us all. That’s horror.

Thanks for reading! Yes, its themes include the treatment of the mentally disabled, the impact on happiness of the conflict between intellect and emotion, and how events in the past can influence a person later in life. The published story starts with a quote from Plato: “Any one who has common sense will remember that the bewilderments of the eye are of two kinds, and arise from two causes, either from coming out of the light or from going into the light, which is true of the mind’s eye, quite as much as of the bodily eye.”