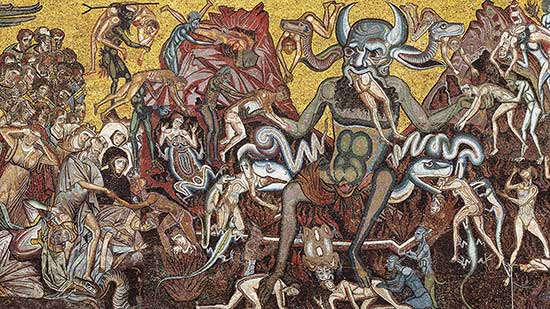

Since its inception as a veritable facet of culture, horror has left its macabre imprint on just about every conceivable art form, from painting to sculpture to literature to film. Even classical composers like J.S. Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Giuseppe Verdi, Béla Bartók, and Richard Wagner used horror as a basis for their work: images of Hell and damnation, Armageddon, ghostly specters and more having provided inspiration for some of their most famous and treasured compositions. And where would silent film classics such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920, Robert Weine), The Golem (1920, Paul Wegener), Nosferatu (1922, F.W. Murnau), Haxan (1922, Benjamin Christensen), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), and Faust (1926, F.W. Murnau) be without their eerie musical accompaniments? Would the opening title cards of Dracula (1931, Tod Browning) be even half as effective without the addition of Russian composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Theme” for Swan Lake? And you can bet Mickey Mouse’s polka-dotted shorts that the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence from Fantasia (1940, the most satanic ten minutes ever to grace a Disney production, by the way) would lose its infernal luster without Modest Mussorgsky’s classical score.

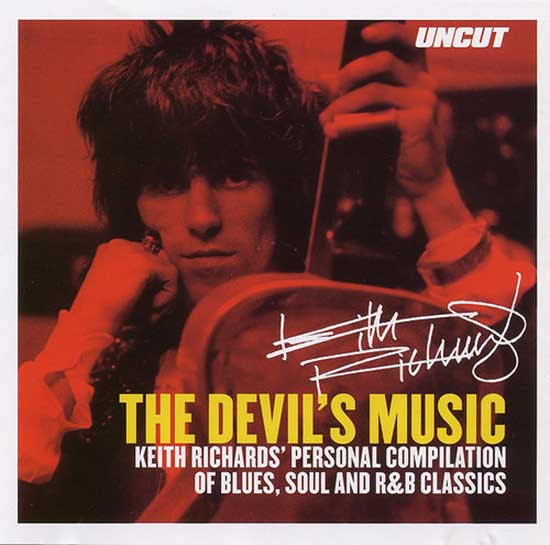

However, it wouldn’t be until the advent of rock n’ roll in the 1950s that darkness and morbidity were overtly personified, even celebrated, within a particular genre of music. Despite being labeled as such for pejorative effect by various self-appointed guardians of morality, rock n’ roll was and will always be, the devil’s music. Is it any wonder then, that there’s such a degree of overlap between horror fans and those of dark rock music? The passion, the morbid romanticism, and the emotional release provided by both rock music and horror genre, and their ability to tackle the kinds of lurid themes that other artistic genres are afraid to touch, make them a fitting and potent pairing.

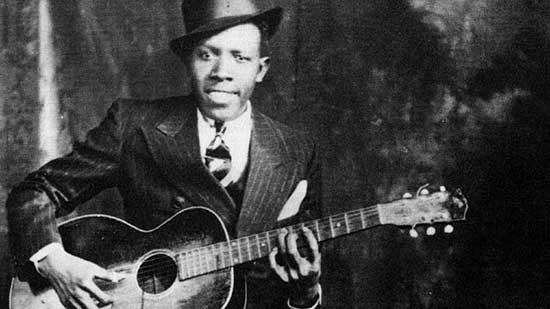

Even before musicians began to appropriate horror imagery into their presentation, rock music was considered a dangerous and bewitching prospect by parents and religious groups on principle. Indeed, nothing was more horrifying in the 1950s to the average parent than Elvis shaking his hips on live TV. Of course, even before rock progenitors like Elvis and Chuck Berry came to the fore, there was the blues, a genre which had its own macabre origins. Take for example, the tale of Robert Johnson- widely considered one of the most influential of all blues players- who supposedly sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for his considerable musical abilities. By the time rock n’ roll moved into the ‘60s, when the genre underwent further definition, it retained the darkly controversial leanings of the early blues.

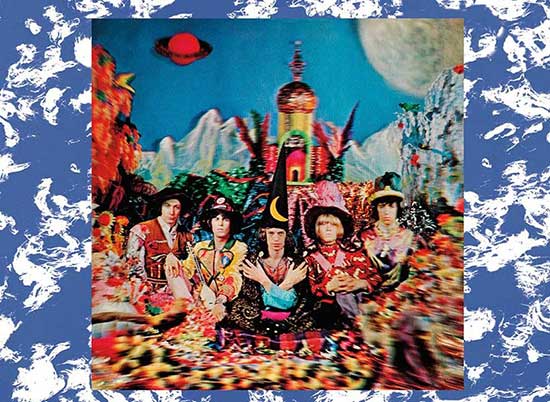

While the Beatles may be credited with laying the basis for modern rock, it was their lewder and rougher contemporaries in The Rolling Stones that pushed the boundary-pushing satanic leanings of the early blues even further. The Stones’ 1967 studio album was entitled Their Satanic Majesties Request, and one of the band’s premier songs: “Sympathy for the Devil”, was an ode to the Fallen Angel, its humanization of Lucifer turning multiple heads upon its release in 1968 (incidentally, the same year that Roman Polanski delivered Rosemary’s Baby, perhaps the defining satanic film).

One of the first musicians to directly utilize horror imagery in his spooky performances was Arthur Brown, rightfully considered the father of “shock rock”, and influencing the sordid theatricality of artists from Alice Cooper to Marilyn Manson to Rob Zombie. On stage, Brown often personified a devilish voodoo priest, howling out lyrics to songs like “Fire” and “I Put a Spell on You”. A few years later, with his debut album Pretties for You, shock-rock showman Alice Cooper proved himself as the logical next evolution of horror-themed rock music. Cooper became known for his ghoulish makeup and lurid stage shows, which included faux decapitations, scenes of torture, and appearances by Kachina, Alice’s pet boa constrictor. Cooper would continue his career into the modern day, always managing to draw on horror literature and cinema for his songs, performances, and music videos. Cooper also made notable contributions to soundtracks in both the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises, as well as appearing in films such as John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness (1987), in which he played a demonic homeless man.

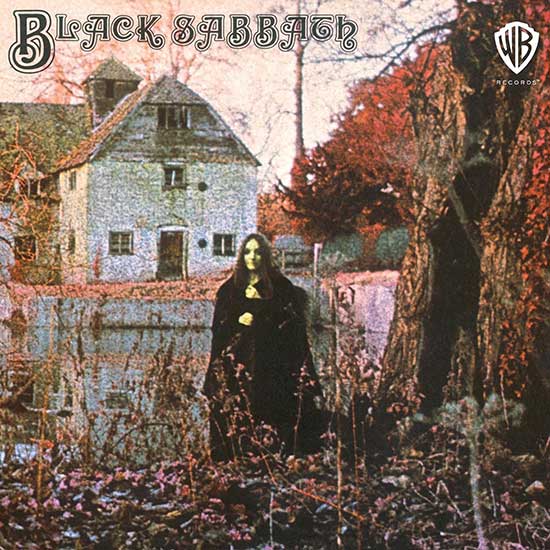

At the start of the ‘70s, from the gloomy industrial hell of Birmingham, England came a band that would forever personify the musical macabre by inventing what is widely-regarded as the scariest form of music in the eyes of the mainstream: heavy metal. That band was, of course, the mighty Black Sabbath. Taking their name from Mario Bava’s classic 1963 anthology film of the same name and comprised of guitar virtuoso Tony Iommi (who sliced off the tips of his fingers with a piece of sheet metal in a factory accident and was informed, wrongly, that he would never play guitar again), the powerhouse rhythm section of bassist Geezer Butler and drummer Bill Ward, and the inimitable frontman Ozzy Osbourne, Sabbath’s distinctly heavy, amplified guitar sound would be panned as “unlistenable noise” by critics at the time. Ironically, publications like Rolling Stone magazine, which eviscerated Sabbath’s first few studio albums at the time of their release, would drastically change their tune during the 1990s when the mainstream was overtaken by the grunge explosion and many of its prominent bands including Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains directly cited Sabbath as a major influence.

But, it wasn’t just Sabbath’s earth-shaking sound that drew ire from their detractors, it was their lyrical preoccupations with death, horror, and the occult. While Sabbath’s hard rock contemporaries in Led Zeppelin, the Who, and Aerosmith were still howling about drugs, booze, mysticism, and sexual promiscuity, Sabbath were involving themselves in more prescient topics suited for the post-Manson ‘70s, such as the horror of war, the end of times, and emotional despair.

Sabbath’s legendary debut album alone is a veritable checklist of morbid influences: “Black Sabbath” depicts the end of days, when sinners are claimed by Satan and dragged into Hell (whilst also utilizing the infamous “tritone”- an unsettling series of notes which were forbidden to musicians during the Dark Ages, for fear that they might conjure demons), “The Wizard” is based on Gandalf from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books, “Behind the Wall of Sleep” is culled from an H.P. Lovecraft story, and “N.I.B” is a love song from the perspective of the Devil himself. As the ‘70s wore on, Black Sabbath’s indispensable early batch of albums (Paranoid, Master of Reality, Vol. 4, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, and Sabotage) would provide a sturdy blueprint for the heavy metal movement of the coming decades.

Thanks to Black Sabbath, heavy metal began to flourish as a distinct genre of music by the 1980s. Considered more lurid and extreme than the average hard rock of the day and containing lyrics that dealt in subversive themes ranging from murder, war, deviant sexuality, and horror imagery, heavy metal reached the apex of its mainstream popularity in this decade. Ozzy Osbourne had been fired from Black Sabbath and decided to go solo for his own shock rock-influenced career that culminated in a live performance in Des Moines, Iowa when the frontman bit the head off a dead bat that a fan had hurled onstage.

Meanwhile, groups such as Dio, Iron Maiden, and Venom drew on horror and fantasy, both for their lyrics and their iconic album covers. Iron Maiden even recycled the “living dead” imagery of George Romero for their beloved zombie mascot, nicknamed “Eddie”. The genre would find itself engulfed in controversy later in the decade during the “satanic panic” years, when religious zealots and hysterical parental groups claimed, with little evidence, that heavy metal, horror films, and the availability of books by occultists like Aleister Crowley and Anton LeVay, were encouraging their children to eschew faith and morality in favor of a fanatical devotion to “the God Below”. The overwhelming prevalence of this kind of reactionary thinking led to several bogus “trials” in which Ozzy Osbourne and Judas Priest were called in to defend songs which supposedly, when played backwards, would encourage thoughts of suicide and satanic worship.

As heavy metal began to leave its indelible mark on pop culture, another musical genre began to take shape, one equally rooted in gothic literature and romanticism: gothic rock. Beginning as an atmospheric offshoot of punk, goth rock was pioneered by post-punk bands such as Joy Division and Bauhaus. With their albums Unknown Pleasures (1979) and especially its follow-up Closer (1980), Joy Division’s abrasive, sepulchral songs often focused on depression, isolation, and death.

Unfortunately, Joy Division’s musical legacy would be cut tragically short with the suicide of tortured frontman Ian Curtis shortly before the release of Closer. Releasing their debut single, “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” (widely regarded as the prototypical goth song) in 1979, Bauhaus burst onto the scene as a mostly underground act. Fronted by the eccentric Peter Murphy, who rocked an array of goth fashion staples such as fishnets, victorian suits, and trenchcoats onstage, Bauhaus served as a primary influence on gothically-inclined bands going forward. Fans of vampire cinema should pay special attention to the opening of Tony Scott’s The Hunger (1983, a cinematic favorite of goths), where Bauhaus plays “Bela” inside a packed goth club as vampiric couple Catherine Deneuve and David Bowie watch from the shadows. The early goth bands helped inspire an entire subculture indebted to gothic literature, horror film imagery, and the romanticization of death and darkness. The sub culture gave rise to its own funereal fashion, as well as gathering places for goth scenesters such as the legendary Batcave club in London, where many a goth band got their start.

The influence of gothic culture was felt deeply within the punk scene as well, with groups like the Damned and the Cramps beginning to appropriate gothic imagery and fashion into their lyrics and visual presentations. Damned frontman Dave Vanian had a tendency for dressing like a vampire onstage and the band (who had already left a lasting mark on the punk scene with their classic debut record, Damned Damned Damned (1977)) began to earnestly embrace the goth scene they helped inspire on their 1980 recording The Black Album (1980), and even more so on 1985’s Phantasmagoria (the artwork for which featured model Susie Bick traipsing through a gloomy cemetery, evoking a sultry Barbara Steele from Black Sunday (1960, Mario Bava)).

The fun rockabilly vibes of The Cramps would help pave the way for punk’s most beloved horror-inspired band: the Misfits. Formed in New Jersey by crooning frontman Glenn Danzig and brothers Jerry Only and Doyle, the Misfits specialized in rousing horror-punk inspired by kitsch horror and sci-fi imagery of the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, with classic tunes such as “Astro Zombies”, “Ghouls Night Out”, “Horror Business”, and “Vampira”. The band’s skull-faced mascot, the Crimson Ghost, would become one of the most iconic and recognizable logos in punk rock history. After the Misfits broke up in 1983 on less-than-amicable terms, Danzig would go on to become a goth icon in his own right with subsequent bands Samhain, which played similar music to that of the Misfits, but more technical and rooted in goth rock.

His eponymous solo act became known for its bluesy, doomy heavy metal sound, set against Danzig’s poetic, occult-based musings. A comparable figure to Danzig, though less tongue-in-cheek, was Australian cult songwriter Nick Cave, who also drew on the blues for his creeping Southern gothic aesthetic. Culling lyrical themes of damnation and despair from the work of writers like William Faulkner, Cave’s moody compositions are as gorgeous as they are unsettling- exemplified by the album Tender Prey, released in 1988 by his band Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Its opening song, “The Mercy Seat” follows a condemned man whose sense of relief at being freed from his ruined existence is palpable as he’s led to the electric chair…

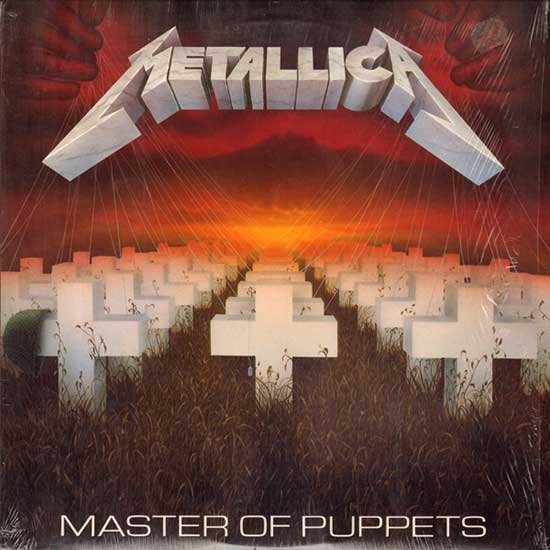

As the ‘80s wore on, developments in both heavy metal and gothic rock began to shape the horror-inspired sounds of music going forward. As the insipid and tacky “hair metal” sound of Poison, Ratt, and Cinderella began to take hold of the mainstream, the metal underground was bustling with the more aggressive and grounded sounds of thrash. Bay area groups such as Metallica, Slayer, Megadeth, and Exodus came to define the sound of thrash, which combined hardcore punk with the speed of early heavy metal acts like Motörhead. The imagery and lyrical preoccupations of the thrash bands provided a morbid counterpoint to the watered-down pop aesthetic being pedaled by the hair metal bands. Metallica for instance, centered on death and mortality on songs such as “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and the title track on their sophomore recording, Ride the Lightning. They also railed against the atrocity of war on their defining 1986 album, Master of Puppets, whilst tackling Lovecraft on classic songs like “The Call of Cthulu” and the granite-heavy “The Thing that Should Not Be”.

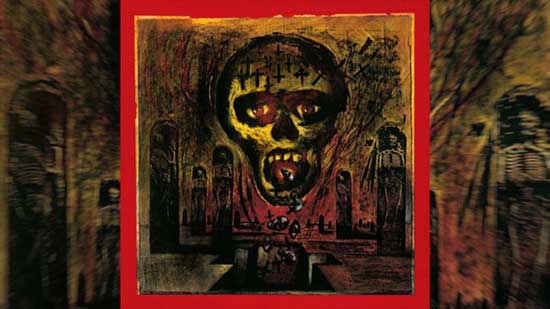

Of all the thrash bands, however, Slayer is unquestionably most indebted to horror’s gruesome evocations of murder, dismemberment, and eternal damnation. With their crowning opus, Reign in Blood, an album steeped in themes of death, Armageddon, Hell, and historical atrocity, Slayer would almost single-handedly give way to the extreme metal movement of the late ‘80s (defined by the two preeminent subgenres of death and black metal). Slayer’s aesthetic also fit firmly in line with the sorts of films dominating the horror genre at the time: slashers and gore films. Meanwhile, in the world of goth rock, harder-edged and arena-ready bands like the Sisters of Mercy and The Cult began to eclipse the artsy, punk-inspired sounds of classic goth bands like Bauhaus, The Cure, and Siouxsie and the Banshees. The Sisters of Mercy in particular, exploding onto the scene with their dancy, proto-industrial hard rock, anticipated the goth metal explosion of the ‘90s by including metal guitars on their final, 1990 release Vision Thing.

By the late ‘80s, thrash, punk, and classic gothic rock had become somewhat stale, so new subgenres emerged. Thanks to the efforts of bands like Venom, Slayer, Celtic Frost, and Candlemass, the genres of death, black, and doom metal began to take shape- lumped under the umbrella term of “extreme metal”. Death metal, exemplified by groups such as Death, Morbid Angel, Obituary, and Cannibal Corpse spun cacophonous lyrical tales of satanism, serial killers, and bodily dismemberment inspired by films like Cannibal Holocaust (1980), The Evil Dead (1981, Sam Raimi), and Re-Animator (1985).

Black metal, on the other hand, grew out of rebellion against the overly-technical nature of death metal. Bands from Scandinavia like Bathory, Mayhem, Emperor, Burzum, and Darkthrone opted for a more primitive, icy, blasphemous sound typified by raspy, shrieking vocals in contrast to the deep-throated, guttural “cookie monster” style of the death metal bands. Black metal also became infamous in Norway, during the early ‘90s, when several teenaged black metal musicians engaged in criminal activities ranging from church arson to murder. This lurid history was touched upon in Jonas Åkerlund’s 2018 film Lords of Chaos, which details the rise and fall of the band Mayhem. Lastly, doom metal continued the tradition of the massive, glacial riffing of Black Sabbath, adding gothic and psychedelic flourishes to sluggishly-paced compositions.

The slow, funereal nature of doom metal provided the perfect meeting place for metal and goth. And it was pioneering Swiss band Celtic Frost that first began to anticipate the union of the two by utilizing gothic atmospherics and ethereal female vocals on their massively-influential 1987 album, Into the Pandemonium. As a bonafide musical movement, however, gothic metal- which set goth rock’s gloomy atmospherics, morbid romanticism, and preoccupation with gothic literature against the massive, morose guitar sound of doom- originated largely in Europe, namely England and Scandinavia. Three bands in particular, all from England: Paradise Lost, My Dying Bride, and Anathema, which began their careers by playing a melancholy fusion of death and doom metal, were credited as being some of the first to meld the gothic sounds of the Sisters of Mercy, the Cure, and Siouxsie and the Banshees to their abrasive styles.

Paradise Lost’s second full-length LP from 1991, aptly titled Gothic, is widely considered to be the album that kickstarted the movement, whilst My Dying Bride’s crushing, but starkly beautiful watershed album Turn Loose the Swans was praised by Rolling Stone on its release as being “Bram Stoker’s Dracula for the ears”. Anathema, meanwhile, peppered lush female vocal accompaniments and Cure-inspired melancholy into their guttural death/doom style on records such as Serenades and its follow-up, The Silent Enigma. The gothic approach wasn’t lost on the black metal scene, either.

Brits Cradle of Filth drew influence from Hammer horror, Clive Barker, Charles Baudelaire, and other such gothic literary maestros to craft a unique fusion of black and gothic metal. Many of Cradle’s early albums were concept records based on gothic literature or morbid history- for example, 1996’s Dusk and Her Embrace was inspired by Sheridan Le Fanu’s classic vampire novella Carmilla, and its follow-up, Cruelty and the Beast, detailed the exploits of sadistic Hungarian countess Elizabeth Bathory. Cradle of Filth opened the floodgates for additional gothically-inclined black metal acts to take center stage, such as Portugal’s Moonspell (basing their debut album, 1995’s Wolfheart, almost entirely around lycanthropy) and Norway’s Gehenna (who added eerie keyboards and gothic soundscapes to the normally-primitive Scandinavian black metal sound). Meanwhile, from Sweden came both Tiamat, whose thundering, darkly psychedelic Wildhoney album is, to this day, considered one of gothic metal’s crowning achievements, and Katatonia, who utilized guttural vocals on their first two landmark records, Dance of December Souls and Brave Murder Day before vocalist Jonas Renkse opted for a smooth, sad baritone reminiscent of Robert Smith on later albums.

While it’s certainly fitting that so many of gothic metal’s key bands hailed from the gloomy, rain and snow-covered streets of England and Scandinavia (England is, after all, where gothic literature originated), it was, in fact, an American band from Brooklyn, New York that became known as the unofficial posterboys of the blossoming gothic metal scene. That band was Type O Negative, fronted by the macabrely charismatic Peter Steele- a nearly-7 foot-tall behemoth of a man whose smooth, booming baritone and vampiric good looks made him a favorite of goth women worldwide. Influenced by his childhood love of horror movies and the music of Black Sabbath and the Beatles, Type O came together from the ashes of Steele’s crossover thrash band, Carnivore. Whilst Carnivore was known as a vehicle for Steele’s ironic, often controversial, sense of humor on topics ranging from politics to women to racism, Type O was something different altogether. The band’s debut record, Slow, Deep and Hard, while still rooted in Steele’s seething misanthropy following an especially bad break-up, showed massive glimmers of the band Type O would become on their sophomore effort, Bloody Kisses, utilizing church-like keyboards, goth atmospherics, and of course, Steele’s vampiric croon. Bloody Kisses, however, was the album that turned Type O from a promising new band to the kings of the gothic metal movement almost overnight. Featuring many of the band’s most beloved, sepulchral hits such as “Christian Woman”, “Blood and Fire”, and the title track, Kisses also boasted the band’s breakthrough hit, “Black No. 1”- a tongue-in-cheek ode to goth women.

The album’s artwork, which couldn’t have more properly suited the music contained within, featured a pair of goth girls in the midst of an erotic embrace. Type O’s follow-up (and the band’s masterpiece, in this writer’s opinion) was the beautiful and more overtly sensual October Rust– the entire album being a lush, autumnal paean to the month of October and the Halloween season. The band followed in 1999 with the heavier and suicidally depressing World Coming Down. This record contained very little of the band’s trademark playfulness in favor of a desolate meditation on death, mourning, and drug addiction. Type O would release two more studio albums: 2003’s Life is Killing Me and 2007’s Dead Again, before Peter Steele tragically passed away in 2010 of sudden heart failure. His presence is sorely missed in the metal community as he was a truly humorous, unique, and morbidly iconic frontman, and (though he would probably beg to differ) a truly accomplished poet and songwriter.

Ethereal female vocals have always been a staple of gothic music, so it wasn’t surprising that female frontwomen became a common staple of the gothic metal movement in the late ‘90s, often accompanied by a guttural male singer. This contrast became known as the “beauty and the beast” aesthetic, and many of its most influential bands, including Norway’s Theatre of Tragedy and Tristania and Italy’s Lacuna Coil, would have a lasting impact on bands like Evanescence, who offered the mainstream a scaled-down, accessible version of the gothic metal sound at the turn of the century. Another horror-influenced musical movement which developed simultaneously with gothic metal was industrial rock/metal. Pioneered by bands like Ministry and Godflesh, who fused pummeling metal guitars with mechanical industrial noise and dance beats.

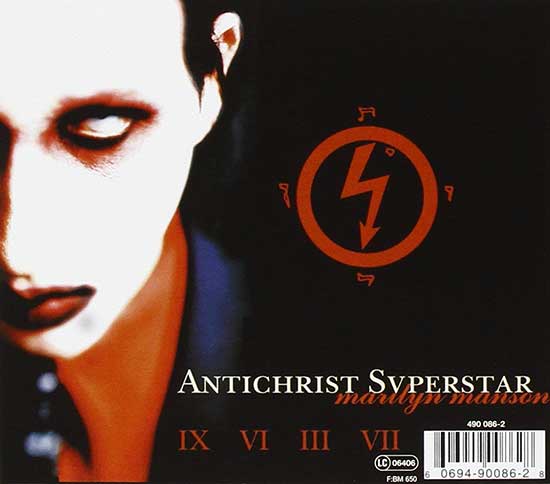

Two of the greatest benefactors of industrial music’s popularity in the post-grunge years of the ‘90s were Trent Reznor’s Nine Inch Nails- which pioneered a more melodic, accessible industrial sound more suited to the mainstream and concocted from an emotionally-intense brew of gothic rock, metal, new wave, and electronic music- and Marilyn Manson, whose industrialized brand of shock rock was originally produced by his friend Reznor. Manson rose from underground success to international stardom with his seminal 1996 concept album, Antichrist Superstar, and became a celebrity boogeyman for parents and conservative groups worldwide. Manson’s grotesque makeup (bringing to mind Winslow Leach’s disfigured visage in Brian de Palma’s classic horror-musical, The Phantom of the Paradise (1974)), his violent imagery and live performances, and his association with Anton LeVay and the Church of Satan were more than enough to win the ire of authority figures throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Manson’s infamy would even come to a head in 1999 when he was recklessly and unfairly blamed by conservative organizations for inspiring the Columbine High School massacre (when, in fact, neither of the two perpetrators were even fans of his music).

The bizarre, graphic, S&M-inspired imagery featured in both Reznor and Manson’s music videos also had a clear impact on horror media in the coming decades- take a look at NIN’s “Closer” video or Manson’s for “The Beautiful People” and compare them to the opening credits for TV’s American Horror Story (2011-present). The similarities are hugely apparent. Also massively successful in the ‘90s industrial metal scene was horror renaissance man Rob Zombie, whose band White Zombie set Pantera-like grooves against horror movie samples for dancy, horror-show recordings like Astro Creep 2000. Zombie would go solo in 1998 with Hellbilly Deluxe, an album which pushed the industrial and dance elements even further and made songs like “Dragula” and “Living Dead Girl” into annual Halloween party staples. German band Rammstein also managed to find great success at the start of the new millennium with their sexually-charged, Reznor/Manson-inspired presentation and their explosive stage shows in which frontman Till Lindemann showed off his penchant for wielding arm-mounted flamethrowers and lighting himself ablaze.

By the early 2000s, the horror-inspired rock movements of goth and industrial had begun to wane in popularity. In vogue were the rap-based sounds of nu metal- a thudding fusion of metal, grunge, and hip-hop pioneered by bands such as Korn, Deftones, and Limp Bizkit- which largely eschewed horror imagery in favor of simple, primitive aggression. The major exception was Iowa’s Slipknot, a nine-piece masked metal ensemble whose frightening disguises and brutal live performances endeared them to fans and made them the logical successors to Marilyn Manson as the next scariest figures in rock.

While their music (which was substantially heavier, more aggressive and technical than the dumbed-down rap-rock of groups like Limp Bizkit) was littered with samples from obscure horror films (attentive listeners will notice Rupert Everett’s “I don’t have time for the living!” line from Michele Soavi’s surreal Italian masterpiece Dellamorte Dellamore (Cemetery Man, 1994) on the track “Diluted” off of 1999’s Slipknot), the members’ attention-grabbing masks betrayed an intimate appreciation of horror culture. Take sampler/keyboardist Craig Jones’ spiked gimp mask, which evoked Hellraiser’s Pinhead, and guitarist Mick Thompson’s metallic hockey mask- clearly inspired by slasher film icons like Jason Voorhees. Slipknot’s career skyrocketed after the release of their 1999 debut, and the group shifted further away from the nu metal movement with their abrasive sophomore effort, Iowa, an album rooted in plentiful death and black metal influences. Iowa also remains by far the most extreme record ever to break the Billboard top 3. 2004’s Vol 3: The Subliminal Verses (produced by Rick Rubin) was more melodic and experimental, and Slipknot continued releasing albums up until last year’s We Are Not Your Kind: a mature and eclectic return to form for the band after their previous two records (2008’s All Hope is Gone and 2014’s .5: The Gray Chapter) came off as commercial obligations rather than genuine artistic statements. As Slipknot dealt with the loss of bassist Paul Gray and infighting which led to the firing of additional band members later in their career, the void had been opened for a new band to fill the macabre theatrical tradition of Alice Cooper, Ozzy, Marilyn Manson, Rob Zombie, and Slipknot.

Thankfully, that band arrived in the form of Sweden’s Ghost, led by the mysterious and charismatic Tobias Forge, whose alter ego, the skull-faced, satanic pope Papa Emeritus, functioned both as a frontman and mascot for the rest of the band- dressed in hooded robes and referred to as “Nameless Ghouls”.

Ghost’s sound was far different from Marilyn Manson’s or Slipknot’s in that it recalled old school doom metal acts like Black Sabbath and Pentagram, as well as the psychedelic rock of Blue Oyster Cult and other bands of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Horror fans will also recognize the band’s cheeky pillaging of iconic horror film imagery gracing their album covers: the band’s debut Opus Eponymous cover mirroring the theatrical poster for Tobe Hooper’s Stephen King TV-adaptation Salem’s ‘Lot (1979) and the artwork for their EP If You Have Ghost mimicking a still from Murnau’s Nosferatu). Ultimately, when Ghost’s “retro” approach was coupled with Forge’s smooth melodic crooning and poppy, satanic songwriting, the band’s recipe for success proved both perplexing and inevitable. Today, after just ten years of being active, Ghost remains one of mainstream metal’s most successful and celebrated acts, their flamboyant live shows successfully melding doom metal with Broadway theatrics.

Heavy metal and its numerous subgenres (thrash, death, black, doom, etc.) are still very much alive and well today and many of them continue to utilize horror aesthetics in a variety of ways. Due to widespread availability of music recording software such as ProTools, many bands and performers have taken it upon themselves to record their own albums and post them to music sharing sites such as Spotify or SoundCloud. The influence of shock rock, goth music, and even that most frowned-upon of subgenres- nu metal- have had a major influence recently on internet rappers and electronic artists such as Lil Ugly Mane and Machine Girl (known for utilizing samples and images from the classic coming-of-age werewolf film Ginger Snaps (2000, John Fawcett)). Even mainstream pop music nowadays is far more inclined to embrace and accept performers’ macabre tendencies. 18-year-old superstar Billie Eilish is a prime example.

She’s often seen sporting gothic fashion in her photoshoots and music videos, and paid homage to The Exorcist (1973, William Friedkin) on the cover of her breakthrough album, last year’s When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? Meanwhile, other contemporary female performers such as the ferocious Chelsea Wolfe and Danish atmospheric black metal artist Myrkur are continuing to push the sounds of extreme metal and gothic rock into the new millennium by pairing them with a wide range of additional influences, ranging from ambient music to folk to shoegaze.

As long as dark, intense, heavy, decadent music continues to thrive (and make no mistake, it will), artists will always be inclined to garner influence from horror literature, film, painting, television, magazines, and other forms of culture. By pairing their auditory palettes with horrific imagery, rock musicians are able to better express the darkness and emotion of their songwriting for their enthusiastic audiences. In the ‘70s, only a band such as Black Sabbath or Alice Cooper could afford to be associated with the types of morbid imagery that today, due to the increased popularity and mainstream acceptance of horror culture, are increasingly commonplace. And for horror fans like myself and others, that’s just the way we want it.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews