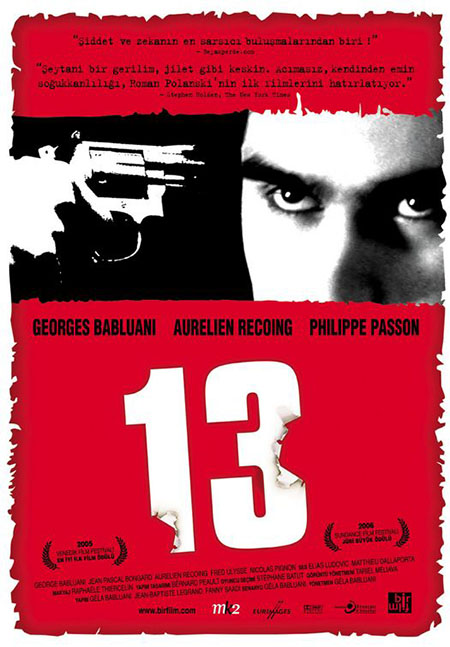

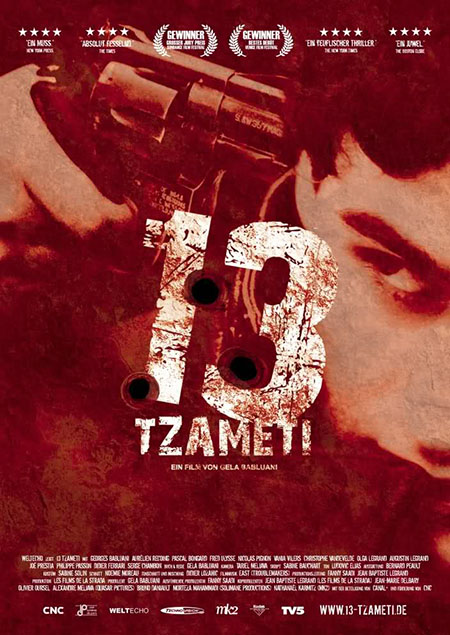

SYNOPSIS:

Sebastian, a young man, has decided to follow instructions intended for someone else, without knowing where they will take him. Something else he does not know is that Gerard Dorez, a cop on a knife-edge, is tailing him. When he reaches his destination, Sebastian falls into a degenerate, clandestine world of mental chaos behind closed doors in which men gamble on the lives of others men.

REVIEW:

Anyone who’s ever listened to an Eli Roth interview about Hostel has probably heard the story about Tarantino biggest contribution to the story: minutiae. According to Tarantino, a storyteller discussing an invented underworld must know everything about day-to-day operations prior to viewers’ arrival—corpse disposal; measures taken to ensure customer privacy; chains of command, and the underworld’s relation to law enforcement.

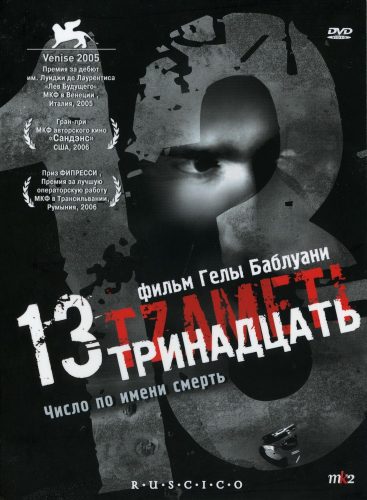

To put it plainly, Gela Babluani’s 13 Tzameti (2005) achieves a level of minutiae more admirable than Hostel could’ve strived for. The underworld of this movie is fleshed out enough to make casual viewers wonder if what they’re witnessing is actually fiction or a well-shot snuff film, more than I can say for the majority of thrillers detailing the extremes of organized depravity.

The movie starts out with a local contractor named Sebastian fixing the roof of a down-and-out criminal who can’t afford to pay him. The criminal, Jean-Francois, gets a striped letter in the mail. The letter contains a train ticket and a receipt for a prepaid hotel room, and Jean-Francois tells his wife it will solve their money problems. Jean-Francois overdoses shortly after receiving the letter, and when Sebastian discovers he wasn’t going to be paid anyway, he steals the letter and boards the train under Jean-Francois’s identity, hoping to claim the big money for himself.

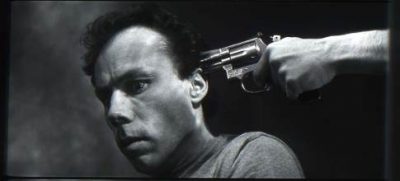

What Sebastian discovers at the end of the train ride is a life-or-death game consisting of 13 players, of which he’s the last. Once he’s arrived and quickly confesses he stole the ticket from Jean-Francois, he’s not allowed to leave, and becomes a game piece for men to gamble on. He’s stripped of his identity, labelled with a number on his back, and is from that point on referred to as “Thirteen.”

The game is simple: players stand in a circle with a hanging lightbulb in the center, and they’re given a revolver with limited bullets in the chamber, the number of bullets increasing with each round of gameplay. They point their revolver at the skull of the person in front of them and stare at the lightbulb; when the bulb turns on, they pull the trigger, and the last man standing wins.

What really sold this movie was the intensity of every player in the circle. Most of the men seemed at first glance to be run of the mill criminal types, with an alluded history of violence and unshakable confidence in their odds of surviving the game. This first impression is quickly shattered: as soon as Sebastian survives the first round, after breaking down and crying, he’s offered a shot of morphine and a heavy belt of liquor, both of which are routinely taken by the other players. It’s quickly apparent these are desperate men, not hardened criminals, and even the nastiest and mouthiest of the bunch fears death as much as Sebastian.

One man is there with his younger brother; another is morbidly obese and can hardly stand on his own; another is throwing up and shaking in the corner of the room, and is dragged kicking and screaming back into the game.

Granted, 13 is a crime thriller with plenty of blood spray and gunfire, but these human qualities made it such a successful film. Very little tops the static shots of Sebastian and the remaining players holding their guns with trembling hands and watching the overhead lightbulb for their cue to pull the trigger.

There have been plenty of inferior movies with similar “murder game” plots, including the English remake of 13 which Babluani directed in 2010. The most apparent example is Rob Zombie’s 31, which stands perfectly fine on its own but is easily eclipsed by the emotional weight and masterful tension of Babluani’s masterpiece. While Zombie’s splatterfest features wealthy aristocrats gambling on players in a hidden room with undisclosed spyware tracking the game’s progress, Babluani’s 13 keep the seedy gamblers in spitting distance of the men they’re watching die, and although most of them appear unapologetic, we at least see emotional tension between their financial straits and the how far they’ll sink morally to win a few dollars.

For as much as 13 really nails minutiae, just enough is left open to ambiguity that audiences can draw their own conclusions about the movie’s implications. Although some things are left ambiguous, at least one timeless question is finally solved: Why was Six afraid of Seven?

Because Seven just blew Nine’s brains out.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews