SYNOPSIS:

“George Orr, a man whose dreams can change waking reality, tries to suppress this unpredictable gift with drugs. Doctor Haber, an assigned psychiatrist, discovers the gift to be real and hypnotically induces Orr to change reality for the benefit of mankind – with bizarre and frightening results.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

In the years immediately following the release of Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977), it was very rare for a science fiction film to rely only on characterisation and plot rather than the usual special effects and spaceship dogfights. The first major made-for-television movie to be produced for the non-profit Public Broadcasting Service of America, The Lathe Of Heaven (1980) is an adaptation of Ursula K. Le Guin‘s award-winning 1971 novel of the same name (an effective parable which reads remarkably like a book by Philip K. Dick, as it was intended by Le Guin as a tribute to that writer, for whom she had expressed intense admiration). Set in the then-near-future year of 1998 in Portland, Oregon, the world is suffocating in an atmosphere contaminated by pollution. The polar ice caps have melted and the problem of overpopulation has become so great that the future of the human race is seriously in doubt. In this sterile world of unending rainfall and a diminishing food supply, no-one is more troubled than George Orr (Bruce Davison), a young man plagued by recurring dreams that, he discovers to his horror upon awakening, change reality, although nobody around him seems to notice.

In order to find a cure for these ‘effective dreams’ Orr is treated by Doctor William Haber (Kevin Conway), a specialist in dream therapy known as an ‘oneirologist’. But rather than try to cure Orr of his unique affliction, Haber instead tries to exploit the young man’s ability to dream effectively for the benefit of all mankind. Using hypnosis, Haber forces Orr to dream-up new realities free from war, pestilence and overpopulation. But Haber’s idealism soon becomes uncontrollable and the side effects of Orr’s dreams often turn out to be disastrous: to cure overpopulation, six billion people die of plague; in trying to unite Earth’s warring population, Orr’s subconscious creates an alien attack on our moon bases and, in attempting to undo the damage, the alien fleet invade Earth. But the aliens turn out to be friendly, and while Orr is forced to dream and dream again, continually seeking Haber’s own notions of Utopia, the invaders warn him that his awesome power is threatening the very fabric of existence and that those who try to use it for themselves will be ‘turned on the lathe of heaven’. In the dramatic climax, Orr must confront Haber for ultimate control as the world crumbles around them and reality comes to an end.

Co-produced and co-directed by Fred Barzyk and David Loxton, The Lathe Of Heaven was filmed on location around Dallas, Fort Worth and the Pacific Northwest, chosen as the backdrop for the movie’s futuristic setting because its many mirrored buildings and unusual architecture made it look futuristic. Many of the scenes were filmed around Dallas City Hall, Reunion Arena, Dallas-Fort Worth Airport and the Fort Worth Water Garden, locations seen in other science fiction films like Logan’s Run (1976) and RoboCop (1987). Barzyk and Loxton met in 1968 at WGBH TV in Boston, and collaborated for two decades, becoming pioneers in the early video art movement until Loxton’s death in the early nineties. The first science fiction drama they created together was the made-for-TV movie Between Time And Timbuktu (1972), based on the work of Kurt Vonnegut Jr. They also created one more tele-movie together, Overdrawn At The Memory Bank (1983), based on the story by John Varley and starring Raul Julia.

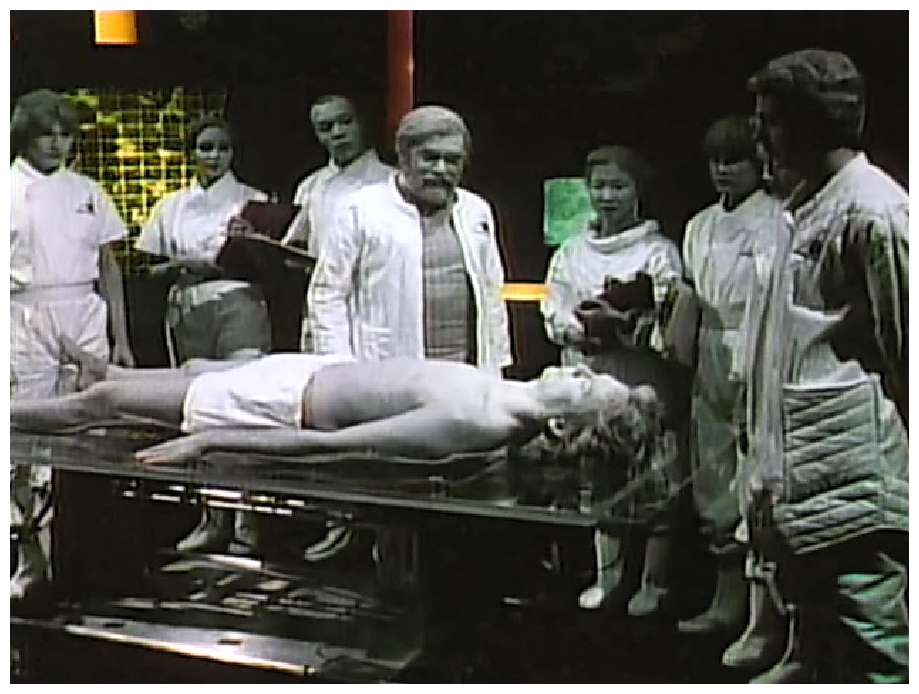

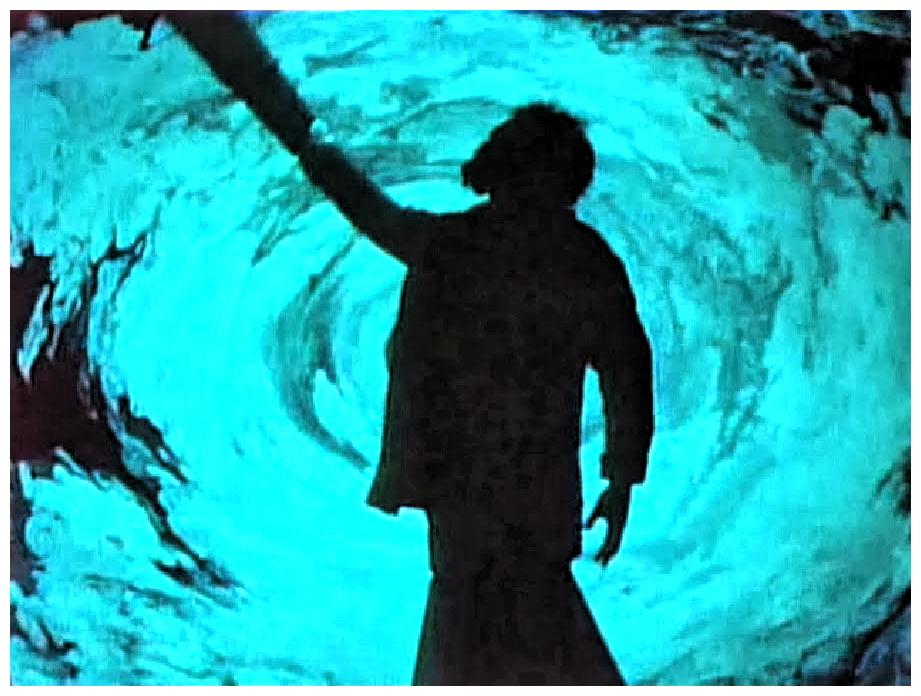

The Lathe Of Heaven had a two-week shooting schedule and a starting budget of about US$250,000, so the filmmakers had to become very creative to effectively convey the novel’s deeper meanings and sometimes grand science fiction scenarios. In one amazing sequence Haber orders Orr to dream away racism, with the unpredictable effect that everyone’s skin, hair and eyes become a ghastly and depressing grey colour (600 extras were spray-painted for the sequence). Barzyk: “David and I had a unique working relationship. We were co-producers, co-directors. If you really cut it down, I would run the set, and David would run behind-the-scenes. But when it came to content and the actual physical structure of the set, we had equal input. The reason that was important, especially on Lathe, is that we had a very limited budget, and we were moving into science fiction and, let’s face it, some of Ursula’s ideas were pretty big. I mean, how the hell do we possibly even begin to portray the attack of aliens or the wiping out of billions of people with the plague?”

“What it came down to was, we had to find metaphors. We had to find things that didn’t cost that much money and still led to maybe the same kind of emotional impact. Our special effects in Lathe were not done the way they were because that was necessarily the direction we wanted to go. It was the direction we had to go. We didn’t have enough money to be able to do these things, so we were constantly trying to figure out ways in which we could shoot something in half a day and imply vast amounts of impressions to the audience. For example, when everyone gets wiped out by the plague, we came up with the idea of putting people around a table and just constantly circling the table and making them distorted and growing older to imply all those people being killed. That was partly because we couldn’t think of any other way to do it within the constraints of our budget. But we were also influenced by video artists. There was one artist who had taken fish-wire and wrapped his face, for example, and so I used a variation of that in this scene.”

“We grabbed from the art director the dust and the smoke and the cobwebs, and in effect we wound up using some of David’s English heritage with the candelabras and the rest, which kind of went back to Great Expectations.” The filmmakers used their meagre budget (which eventually tripled to almost US$800,000) marvellously. Although the effects are simple, Loxton and Barzyk utilised the talents of award-winning illustrator Ed Emshwiller, composer Laurie Spiegel and CGI artist Lillian Schwartz to create special sound effects, graphic displays and scenic design concepts for many visually stunning key sequences. Ursula Le Guin herself worked as creative consultant on the film to make sure that her story was faithfully adapted by screenwriters Roger Swaybill and Diane English. In fact Le Guin and her family appear as extras in a scene where Heather (Margaret Avery) and George talk over lunch in a cafeteria (on the night it was first screened there was a major power outage in the Pacific Northwest, and the author was able to watch only the first couple of minutes before the blackout).

Filming on location using futuristic buildings gives the movie a realistic look that even the best special effects and matte paintings fail to capture. Only the sympathetic aliens are unconvincing and show signs of budget restrictions. Looking like man-sized turtles with glowing heads, the film cries out for the friendly-looking space travellers of, say, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977). The Lathe Of Heaven was originally intended to be the first in a series of made-for-TV movies that would bring the work of serious science fiction authors to the television screen and debuted on PBS on the 9th January 1980. For an audience that had become used to space operas, the film was a revelation and garnered enthusiastic reviews. The questions that the film leaves its audience to ponder – like all good science fiction – may help us to avoid the nightmare world that a dying George Orr staggers through in the movie’s opening minutes. The Lathe Of Heaven is ambitious and imaginative science fiction cinema at its best.

That it came from the wasteland of American television during that time makes it even more remarkable. It’s certainly a film that deserves the widest possible showing, but it remained unseen for twenty years because of one tiny copyright issue – at one point George Orr plays a record of With a Little Help From My Friends by The Beatles. The film was finally allowed to be rebroadcast when The Beatles version of the song was replaced with one sung by a different vocalist. Screened again after two decades absence sparked enough interest in a remake, resulting in Lathe Of Heaven (2002), directed by Philip Haas and starring James Caan, Lukas Haas and Lisa Bonet. Unlike the 1980 adaptation, it throws out a significant portion of the plot, some minor characters, and much of the philosophical underpinnings of the book, but that’s another story for another time. At this point I’d like to thank my regular readers, and recommend my irregular readers eat more fibre. Until we meet again, toodles!

The Lathe Of Heaven (1980)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews