SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

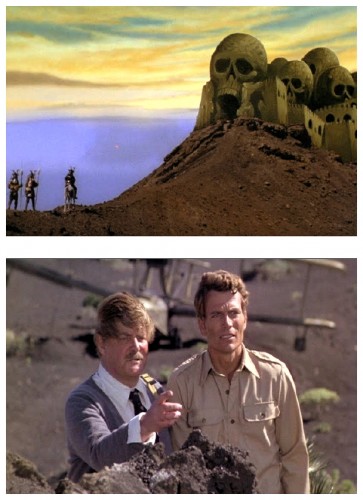

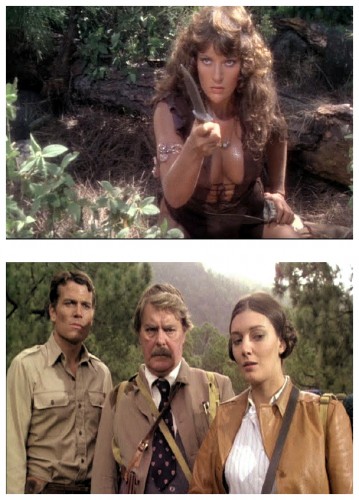

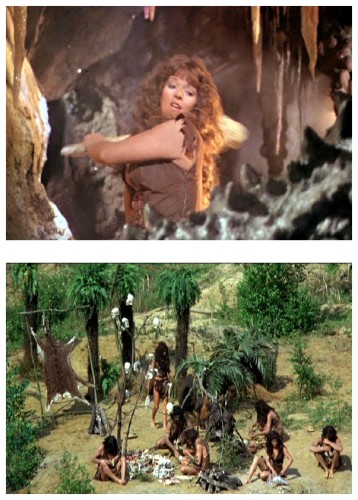

“After a German U-Boat sinks their ship, several survivors manage to take control of the boat. Bowen Tyler is the son of an American shipbuilder and Captain Bradley an experienced seaman. After several tussles with the German crew, they find themselves on a strange island. There they find a place where several stages of Earth’s evolution co-exist at the same time. As a result several types of humans are found as well as prehistoric dinosaurs. There are also active volcanoes which all add up to a challenge to survive.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

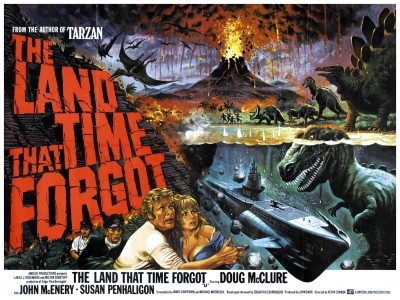

Inspired by their successful collaboration producing the innovative witchcraft film Horror Hotel (1960) also known as The City Of The Dead, Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg founded Amicus Productions based at Shepperton Studios in England. After a couple of light-hearted teen musicals in order to kick-start the company, Amicus went on to make a series of portmanteau horror anthologies inspired by the grandfather of all anthology films, Dead Of Night (1945). They include such gaudy titles as Doctor Terror’s House Of Horrors (1964), Torture Garden (1967), The House That Dripped Blood (1970), Tales From The Crypt (1972), Asylum (1972), Vault Of Horror (1973) and From Beyond The Grave (1974). These films usually had four or five short horror stories linked by an overarching plot featuring a narrator and those listening to his story. It was about this time that Amicus decided to dabble in science fiction with a number of films based on the stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

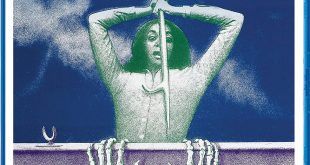

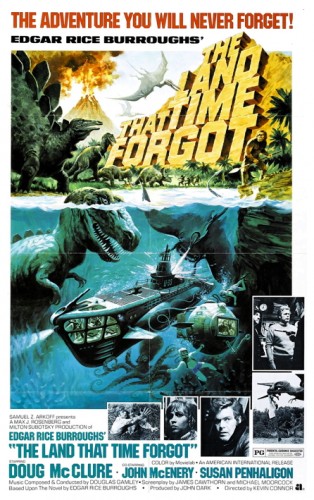

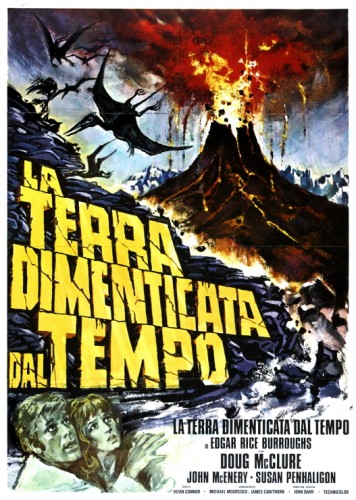

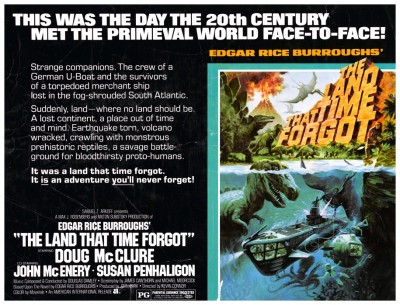

The first of these was The Land That Time Forgot (1975), a ‘lost-world’ fantasy aimed at family audiences. It proved a great success and spawned a number of sequels including At The Earth’s Core (1976), The People That Time Forgot (1977) and Warlords Of Atlantis (1978). Directed by Kevin O’Connor, The Land That Time Forgot concerned a strange land inhabited by dinosaurs and primitive tribes which is discovered during World War One by a German submarine, crewed by a mixture of German and British seamen, and one American hero (Doug McClure). It would have been an ideal subject for Ray Harryhausen‘s model animation, but alternative methods were used to create the dinosaurs. Special effects supervisor Derek Meddings, who I was lucky enough to meet on the set of Spies Like Us (1985), explained why:

The first of these was The Land That Time Forgot (1975), a ‘lost-world’ fantasy aimed at family audiences. It proved a great success and spawned a number of sequels including At The Earth’s Core (1976), The People That Time Forgot (1977) and Warlords Of Atlantis (1978). Directed by Kevin O’Connor, The Land That Time Forgot concerned a strange land inhabited by dinosaurs and primitive tribes which is discovered during World War One by a German submarine, crewed by a mixture of German and British seamen, and one American hero (Doug McClure). It would have been an ideal subject for Ray Harryhausen‘s model animation, but alternative methods were used to create the dinosaurs. Special effects supervisor Derek Meddings, who I was lucky enough to meet on the set of Spies Like Us (1985), explained why:

“I’m a great fan of Harryhausen’s work but there are some people who aren’t, so I can’t always say to a film company, ‘I think you should get Harryhausen.’ Besides, he’s always busy with his own films, and Jim Danforth – the other animation specialist – is always busy too. With The Land That Time Forgot we couldn’t get involved in animating models ourselves because it takes so long, it means spending a year of your life just animating models. And apart from Harryhausen, there’s not really anyone in England set-up to do model animation. If you start on a medium-budget picture, the company concerned just can’t afford to set you up in such a specialist operation either, whereas Harryhausen can set himself up whenever he wants. He gets paid a lot of money to do it and he does it very successfully. There’s no-one to beat him, really.”

“I’m a great fan of Harryhausen’s work but there are some people who aren’t, so I can’t always say to a film company, ‘I think you should get Harryhausen.’ Besides, he’s always busy with his own films, and Jim Danforth – the other animation specialist – is always busy too. With The Land That Time Forgot we couldn’t get involved in animating models ourselves because it takes so long, it means spending a year of your life just animating models. And apart from Harryhausen, there’s not really anyone in England set-up to do model animation. If you start on a medium-budget picture, the company concerned just can’t afford to set you up in such a specialist operation either, whereas Harryhausen can set himself up whenever he wants. He gets paid a lot of money to do it and he does it very successfully. There’s no-one to beat him, really.”

Derek Meddings found work in the late forties at Denham Studios lettering credit titles, and it was there that he met effects designer Les Bowie who invited him to join the matte painting department. Meddings first worked with producer Gerry Anderson in the late fifties as an art assistant on Torchy The Battery Boy and Four Feather Falls (1960) and, after Supercar and Fireball XL5, he was promoted to effects director for Stingray. From 1965 to 1970 Meddings reached his productive peak supervising special effects on no less than five television series – Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet And The Mysterons, Joe 90, The Secret Service, U.F.O. – and three feature films – Thunderbirds Are Go (1966), Thunderbird Six (1968) and Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun (1969). By the mid-seventies Meddings had finally hit the big-time supervising the effects on box-office blockbusters like the James Bond, Superman The Movie (1978) and Batman (1989) franchises, but not before struggling on a few smaller projects such as Zero Population Growth (1972) and The Land That Time Forgot.

Derek Meddings found work in the late forties at Denham Studios lettering credit titles, and it was there that he met effects designer Les Bowie who invited him to join the matte painting department. Meddings first worked with producer Gerry Anderson in the late fifties as an art assistant on Torchy The Battery Boy and Four Feather Falls (1960) and, after Supercar and Fireball XL5, he was promoted to effects director for Stingray. From 1965 to 1970 Meddings reached his productive peak supervising special effects on no less than five television series – Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet And The Mysterons, Joe 90, The Secret Service, U.F.O. – and three feature films – Thunderbirds Are Go (1966), Thunderbird Six (1968) and Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun (1969). By the mid-seventies Meddings had finally hit the big-time supervising the effects on box-office blockbusters like the James Bond, Superman The Movie (1978) and Batman (1989) franchises, but not before struggling on a few smaller projects such as Zero Population Growth (1972) and The Land That Time Forgot.

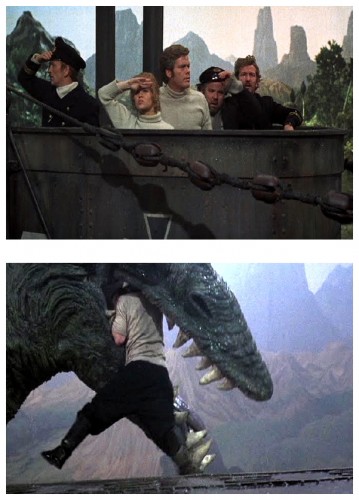

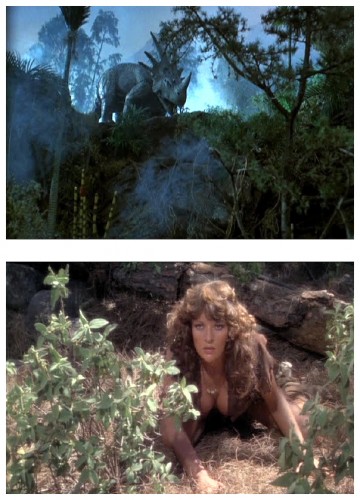

“In The Land That Time Forgot we used model dinosaurs that were about three foot high on average and were manipulated either mechanically or like glove puppets, with someone’s hand inside them. They weren’t made by my team or me, but by Roger Dicken. We were involved in the filming of them and we also helped him operate them because obviously he couldn’t operate them all at once. It was complicated because we had to make them move and attack people but, as they were basically puppets it was difficult to show them actually walking, so we had to use a lot of tricks. To combine them in the same scenes with the actors, we used front-projection (supervised by Charles Staffel).” One of the better sequences involves an aquatic dinosaur, consisting of a huge head and a long neck, suddenly appearing next to the submarine and attacking the crew on deck.

“In The Land That Time Forgot we used model dinosaurs that were about three foot high on average and were manipulated either mechanically or like glove puppets, with someone’s hand inside them. They weren’t made by my team or me, but by Roger Dicken. We were involved in the filming of them and we also helped him operate them because obviously he couldn’t operate them all at once. It was complicated because we had to make them move and attack people but, as they were basically puppets it was difficult to show them actually walking, so we had to use a lot of tricks. To combine them in the same scenes with the actors, we used front-projection (supervised by Charles Staffel).” One of the better sequences involves an aquatic dinosaur, consisting of a huge head and a long neck, suddenly appearing next to the submarine and attacking the crew on deck.

“That head and its mechanism was built at Shepperton Studios and they did a fantastic job on it, but the funny thing was that it got full of water every time we ducked it under, despite having been made of waterproofed non-absorbent material, and it got heavier and heavier. As you know it had to snatch a German sailor off the deck of the sub and plunge him underwater – well, we used an actor up to a certain point in the action, and then we had to use a stuntman for when he actually went into the water, and inside the head was an aqualung so that the stuntman could breathe when the head was under the surface. We did the shot several times and each time it got harder to raise the thing because of all the water it had absorbed. It got so heavy we had to use a block-and-tackle on it and pull it up very gently. We had a mechanism inside, like a hydraulic arm, and everything started to pull against it as the material got more and more waterlogged, but we got the shot we wanted…eventually.”

“That head and its mechanism was built at Shepperton Studios and they did a fantastic job on it, but the funny thing was that it got full of water every time we ducked it under, despite having been made of waterproofed non-absorbent material, and it got heavier and heavier. As you know it had to snatch a German sailor off the deck of the sub and plunge him underwater – well, we used an actor up to a certain point in the action, and then we had to use a stuntman for when he actually went into the water, and inside the head was an aqualung so that the stuntman could breathe when the head was under the surface. We did the shot several times and each time it got harder to raise the thing because of all the water it had absorbed. It got so heavy we had to use a block-and-tackle on it and pull it up very gently. We had a mechanism inside, like a hydraulic arm, and everything started to pull against it as the material got more and more waterlogged, but we got the shot we wanted…eventually.”

Less impressive was the pterodactyl used in the sequence in which a caveman is snatched up and carried away. “That we weren’t very pleased with. It worked all right in the film though. We built a full-sized model which was suspended from a crane, for the shot where it swoops down and picks him up, and for the shot showing it flying off with the man in its mouth, we used a smaller model. The man was a model in that shot too, and he contained a mechanism that moved his arms and legs.” Possibly the best effects in the film involve the German submarine, which was a model over twenty feet in length. “There were four of us working on that. We built the sub and filmed it in the largest tank at the studio. It moved on an underwater track and we were underwater ourselves a lot of the time shooting it. We lived like fish for about six weeks filming that thing!”

Less impressive was the pterodactyl used in the sequence in which a caveman is snatched up and carried away. “That we weren’t very pleased with. It worked all right in the film though. We built a full-sized model which was suspended from a crane, for the shot where it swoops down and picks him up, and for the shot showing it flying off with the man in its mouth, we used a smaller model. The man was a model in that shot too, and he contained a mechanism that moved his arms and legs.” Possibly the best effects in the film involve the German submarine, which was a model over twenty feet in length. “There were four of us working on that. We built the sub and filmed it in the largest tank at the studio. It moved on an underwater track and we were underwater ourselves a lot of the time shooting it. We lived like fish for about six weeks filming that thing!”

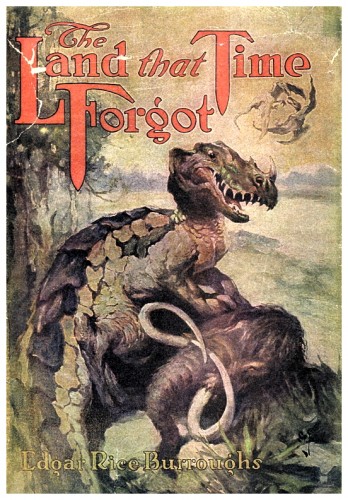

Surprisingly, one of the two scriptwriters who worked on the screenplay was an actual science fiction author, one of the best, none other than the award-winning best-selling Michael Moorc**k. The following is a transcript of Mr. Moorc**k in conversation with critic John Baxter: “I became involved when Edgar Rice Burroughs Incorporated (ERB Inc.) slung out the first script that Amicus submitted to them – I’ve still got a copy of it somewhere and it’s incredibly meaningless gibberish. ERB Inc. said they wanted a new script so the producer, Milton Subotsky, phoned my agent and asked if she knew of anyone suitable and thought that I was an ideal choice and I said yeah, I’ll do it if Jim Cawthorn could do the script with me, because I knew that he’s always wanted to work on an Edgar Rice Burroughs film. And because of the mess that had come about from me not being able to do the script on The Final Programme (1973) I thought, here’s a chance to learn how to write a script and get paid for it at the same time.”

Surprisingly, one of the two scriptwriters who worked on the screenplay was an actual science fiction author, one of the best, none other than the award-winning best-selling Michael Moorc**k. The following is a transcript of Mr. Moorc**k in conversation with critic John Baxter: “I became involved when Edgar Rice Burroughs Incorporated (ERB Inc.) slung out the first script that Amicus submitted to them – I’ve still got a copy of it somewhere and it’s incredibly meaningless gibberish. ERB Inc. said they wanted a new script so the producer, Milton Subotsky, phoned my agent and asked if she knew of anyone suitable and thought that I was an ideal choice and I said yeah, I’ll do it if Jim Cawthorn could do the script with me, because I knew that he’s always wanted to work on an Edgar Rice Burroughs film. And because of the mess that had come about from me not being able to do the script on The Final Programme (1973) I thought, here’s a chance to learn how to write a script and get paid for it at the same time.”

“I knew Amicus would only be paying peanuts – I think I got paid a thousand quid – but it would only be for a week’s work, which is really all it was. And as ERB Inc. were putting up half the money for the film, they were insisting that the script be close to the original book, which is just how Jim and I wanted to write it. With them behind us we thought we were pretty safe but, of course, Amicus screwed it up and put in the volcano and all the usual stuff. None of that was in our script, we had what they would have regarded as a downbeat ending. It doesn’t matter how many times you tell them that the most successful films, like Frankenstein (1931) and King Kong (1933), have sort-of tragic endings, they still feel you have to have some kind of up-beat ending, like an exploding volcano. Our ending followed the book’s pretty faithfully. It wasn’t a profound book, but it was the most interesting one, I felt, that Edgar Rice Burroughs had ever written. It was one of the few books of his that had an idea of some interest: the island as some sort of womb.”

“I knew Amicus would only be paying peanuts – I think I got paid a thousand quid – but it would only be for a week’s work, which is really all it was. And as ERB Inc. were putting up half the money for the film, they were insisting that the script be close to the original book, which is just how Jim and I wanted to write it. With them behind us we thought we were pretty safe but, of course, Amicus screwed it up and put in the volcano and all the usual stuff. None of that was in our script, we had what they would have regarded as a downbeat ending. It doesn’t matter how many times you tell them that the most successful films, like Frankenstein (1931) and King Kong (1933), have sort-of tragic endings, they still feel you have to have some kind of up-beat ending, like an exploding volcano. Our ending followed the book’s pretty faithfully. It wasn’t a profound book, but it was the most interesting one, I felt, that Edgar Rice Burroughs had ever written. It was one of the few books of his that had an idea of some interest: the island as some sort of womb.”

“Another problem that occurred during the filming was that the actor John McEnery, who played the U-Boat captain, did his whole part as a send-up and wrecked a lot of the tension of the film because, in our version of the script, the German was more-or-less the central character. We didn’t want the usual Burroughs 1916 ranting Hun, so we made him the philosophical core of the film. We gave him speeches and everything, we made him a ‘sensitive Kraut’ but McEnery played the whole thing for laughs. They had to re-dub all his dialogue with Anton Diffring. Most of the action in the film came from our script up until two-thirds through. They improved on the beginning by making cuts – we made as many as we could because most of the book is all in that bloody submarine with them taking turns in taking it over.”

“I try to be as professional as possible in whatever I do, but I knew it would be silly to get too serious about a film like this. Anyway, before Jim and I started, as I wanted to do the best I could for the film, I asked Amicus, ‘What’s the budget? What can you afford to do?’ Because if we knew what they could afford we could write the script accordingly. And they said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about that’. And they kept saying that, so in the end we just had to write the script in the dark as far as the budget was concerned and, as a result, about five hundred bleeding dinosaurs came down to one glove puppet. But working on that film was in no way as traumatic as The Final Programme experience had been because I had no personal involvement with it, none at all. I insisted at the beginning that we do one script, one version, and that would be it, and that was the way we did it. We delivered the script and we got the money…after some time. I think they finally paid us in monthly installments.”

“I try to be as professional as possible in whatever I do, but I knew it would be silly to get too serious about a film like this. Anyway, before Jim and I started, as I wanted to do the best I could for the film, I asked Amicus, ‘What’s the budget? What can you afford to do?’ Because if we knew what they could afford we could write the script accordingly. And they said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about that’. And they kept saying that, so in the end we just had to write the script in the dark as far as the budget was concerned and, as a result, about five hundred bleeding dinosaurs came down to one glove puppet. But working on that film was in no way as traumatic as The Final Programme experience had been because I had no personal involvement with it, none at all. I insisted at the beginning that we do one script, one version, and that would be it, and that was the way we did it. We delivered the script and we got the money…after some time. I think they finally paid us in monthly installments.”

“Actually I quite enjoyed the picture when I finally saw it completed. I took the kids to see it where ever it was on in the West End and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I love dinosaur pictures anyway. The dinosaurs themselves were something of a disappointment in some ways but there were some static scenes that were quite good – like one long shot where you saw a dinosaur on a cliff – and there were similar shots I liked. Obviously the rest of it was a shambles, but I can always go a long way with the helping of my imagination.” Michael Moorc**k and Jim Cawthorn were supposed to write the script for the sequel entitled At The Earth’s Core (1976) based on another novel by Burroughs but, after a disagreement with Amicus producer John Dark, Moorc**k pulled out of the project and the treatment he and Cawthorn had written was never used. But that’s another story about another film for another time. Right now I’ll bid you a good night and pleasant dreams, but not before profusely thanking Films And Filming magazine November 1977 for their invaluable assistance in researching this article. I’m convinced you’ll show your gratitude too, by popping in again next week when I dig-up another terror from beyond the bottom of the garden path for…Horror News! Toodles!

“Actually I quite enjoyed the picture when I finally saw it completed. I took the kids to see it where ever it was on in the West End and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I love dinosaur pictures anyway. The dinosaurs themselves were something of a disappointment in some ways but there were some static scenes that were quite good – like one long shot where you saw a dinosaur on a cliff – and there were similar shots I liked. Obviously the rest of it was a shambles, but I can always go a long way with the helping of my imagination.” Michael Moorc**k and Jim Cawthorn were supposed to write the script for the sequel entitled At The Earth’s Core (1976) based on another novel by Burroughs but, after a disagreement with Amicus producer John Dark, Moorc**k pulled out of the project and the treatment he and Cawthorn had written was never used. But that’s another story about another film for another time. Right now I’ll bid you a good night and pleasant dreams, but not before profusely thanking Films And Filming magazine November 1977 for their invaluable assistance in researching this article. I’m convinced you’ll show your gratitude too, by popping in again next week when I dig-up another terror from beyond the bottom of the garden path for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews