SYNOPSIS:

“Jonathan Frid portrays horror novelist Edmund Blackstone who has a recurring nightmare about three figures out of his book who terrorise him and his family and friends during a weekend of fun. When Blackstone begins to write, the three figures appear at his home and the dream becomes reality.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

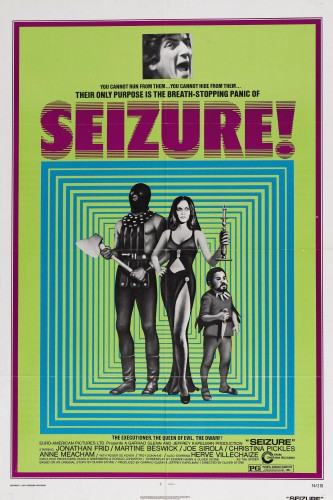

Screenwriting alone could not contain Oliver Stone‘s creative impulses back in 1973 so, after co-writing a script with Edward Mann, Ollie decided to direct. Seizure (1974), also known in various countries as Queen Of Evil or Tango Macabre, concerns horror author Edmund Blackstone (Jonathan Frid) who is plagued by nightmares. He and his wife (Christina Pickles) invite a number of guests to their isolated country house for a relaxing weekend but, after a few go missing, they are confronted with three villainous characters from Edmund’s imagination, the physical manifestations of his nightmares: The provocative and sultry Queen Of Evil (Martine Beswick), the giant strongman Jackal (Henry Judd Baker) and a dwarf assassin named Spider (Hervé Villechaize). The trio’s antics are both amusing and unsettling, as many of Edmund’s guests are either killed or forced to go through a series of tests to see who deserves to live. The first to die is the family dog, found hung by the neck from his leash.

And so it goes in Seizure, Ollie’s little-seen directorial debut, a low budget horror film made in Quebec. In 1991 he confessed: “You have to stretch to like it. It wasn’t great. I felt back then the same as I do now, that I always wanted to direct, and the horror genre was easier to break in with.” As schlocky as Seizure is, it still shows a certain style that can charitably be called seminal Stone. Its archetypes of evil would show up later in a more subtle form – Tom Berenger as the amoral lieutenant in Platoon (1986), Michael Douglas as the unscrupulous trader of Wall Street (1987), the murderous Mickey in Natural Born Killers (1994).

And so it goes in Seizure, Ollie’s little-seen directorial debut, a low budget horror film made in Quebec. In 1991 he confessed: “You have to stretch to like it. It wasn’t great. I felt back then the same as I do now, that I always wanted to direct, and the horror genre was easier to break in with.” As schlocky as Seizure is, it still shows a certain style that can charitably be called seminal Stone. Its archetypes of evil would show up later in a more subtle form – Tom Berenger as the amoral lieutenant in Platoon (1986), Michael Douglas as the unscrupulous trader of Wall Street (1987), the murderous Mickey in Natural Born Killers (1994).

Oliver Stone paints large canvases, and his movies tend to excess, beginning with Seizure, in which there is not one but three forces of evil. There’s not just cocaine use in Scarface (1983) – for which he wrote the screenplay – there are huge mountains of it. There’s not just a change of heart for the disillusioned Vietnam vet in the double-Oscar-winner Born On The Fourth Of July (1989) – he goes on a holy crusade that lasts more than two hours. Even an early screenplay like Midnight Express (1978) had Brad Davis not only imprisoned in Turkey on marijuana charges, but virtually thrown into Hell. The wars outside (Vietnam, El Salvador, etc.) and the wars inside (ethics, drug use, etc.) rage across screens that have been painted by Ollie.

Oliver Stone paints large canvases, and his movies tend to excess, beginning with Seizure, in which there is not one but three forces of evil. There’s not just cocaine use in Scarface (1983) – for which he wrote the screenplay – there are huge mountains of it. There’s not just a change of heart for the disillusioned Vietnam vet in the double-Oscar-winner Born On The Fourth Of July (1989) – he goes on a holy crusade that lasts more than two hours. Even an early screenplay like Midnight Express (1978) had Brad Davis not only imprisoned in Turkey on marijuana charges, but virtually thrown into Hell. The wars outside (Vietnam, El Salvador, etc.) and the wars inside (ethics, drug use, etc.) rage across screens that have been painted by Ollie.

Another typical Stone image is the Christ-like martyr who dies for our sins, beginning in Seizure with the faithful family dog hanging from a tree. Later, there would be Dafoe’s famous pose on the posters for Platoon (1986), kneeling with his arms outstretched in final agony, and Val Kilmer as Jim Morrison blissfully breaking through to the other side in The Doors (1991). Female characters have never been Ollie’s strong suit, and those in Seizure are no exception. The Queen Of Evil is everything a man could want and dread at the same time, the majestic embodiment of all our desires and thoughts – the alluring eternal female of our soul, she is both mother and whore. Edmund’s own wife is a complete bitch (“You’re a worm, Edmund, a lump of mud! You want to live and you don’t know how!”), and genre darling Mary Woronov plays a houseguest who chooses to wear a bikini when wrestling Edmund to the death.

Another typical Stone image is the Christ-like martyr who dies for our sins, beginning in Seizure with the faithful family dog hanging from a tree. Later, there would be Dafoe’s famous pose on the posters for Platoon (1986), kneeling with his arms outstretched in final agony, and Val Kilmer as Jim Morrison blissfully breaking through to the other side in The Doors (1991). Female characters have never been Ollie’s strong suit, and those in Seizure are no exception. The Queen Of Evil is everything a man could want and dread at the same time, the majestic embodiment of all our desires and thoughts – the alluring eternal female of our soul, she is both mother and whore. Edmund’s own wife is a complete bitch (“You’re a worm, Edmund, a lump of mud! You want to live and you don’t know how!”), and genre darling Mary Woronov plays a houseguest who chooses to wear a bikini when wrestling Edmund to the death.

If Seizure doesn’t immediately bring to mind the grand scheme of JFK (1991), which is about a moment in time and politics that changed the way America thinks about itself, still it is only a Stone’s throw away (get it?) from The Hand (1981), his second directing job, and the one most people think is his first. Michael Caine plays a newspaper cartoonist whose career and marriage are cut short when he loses his hand in a car accident, but the digits crawl back to kill off some of the artist’s detractors. Just as in Seizure, the artist’s creations are so powerful that they can carry out their master’s hidden agenda or even turn on him. In both early movies, symbols of the creative spirit (the writer’s imagination, the artist’s hand) act out the artist’s subconscious desires, particularly fantasies of revenge and megalomania.

If Seizure doesn’t immediately bring to mind the grand scheme of JFK (1991), which is about a moment in time and politics that changed the way America thinks about itself, still it is only a Stone’s throw away (get it?) from The Hand (1981), his second directing job, and the one most people think is his first. Michael Caine plays a newspaper cartoonist whose career and marriage are cut short when he loses his hand in a car accident, but the digits crawl back to kill off some of the artist’s detractors. Just as in Seizure, the artist’s creations are so powerful that they can carry out their master’s hidden agenda or even turn on him. In both early movies, symbols of the creative spirit (the writer’s imagination, the artist’s hand) act out the artist’s subconscious desires, particularly fantasies of revenge and megalomania.

Starting with Seizure, the psychology of Ollie’s protagonists is rooted in the early omnipotent fantasies of childhood, when children experience alternate rushes of megalomania and guilt because they believe their bad thoughts can really reach out and harm others. “It’s the classic novelist’s nightmare, only the nightmare is happening in real life. Is the writer creating the monster within him? There is confusion about whether he is a victim or doing the victimising.”

Starting with Seizure, the psychology of Ollie’s protagonists is rooted in the early omnipotent fantasies of childhood, when children experience alternate rushes of megalomania and guilt because they believe their bad thoughts can really reach out and harm others. “It’s the classic novelist’s nightmare, only the nightmare is happening in real life. Is the writer creating the monster within him? There is confusion about whether he is a victim or doing the victimising.”

One last important aspect of Ollie’s career, from a behind-the-scenes standpoint that probably has as much to do with his own personality as with the harsh realities of Hollywood, is that his films offer seemingly impossible challenges. He’s not simply an in-your-face filmmaker, but a standard-bearer sparked by adversity – the more difficult the path, the more spectacular the result. Ollie had to personally smuggle the work print of Seizure out of Canada and sell it in the USA because they had run out of money, and the film finally opened to sparse attendance in New York on Forty-Second Street amongst cinemas more accustomed to screening chop-socky double-features. I’ll now quickly thank The Washington Post and Video Magazine for assisting me in my research for this review, and graciously invite you to please join me again next week when I return with another daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensation found in that steaming cesspit known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

One last important aspect of Ollie’s career, from a behind-the-scenes standpoint that probably has as much to do with his own personality as with the harsh realities of Hollywood, is that his films offer seemingly impossible challenges. He’s not simply an in-your-face filmmaker, but a standard-bearer sparked by adversity – the more difficult the path, the more spectacular the result. Ollie had to personally smuggle the work print of Seizure out of Canada and sell it in the USA because they had run out of money, and the film finally opened to sparse attendance in New York on Forty-Second Street amongst cinemas more accustomed to screening chop-socky double-features. I’ll now quickly thank The Washington Post and Video Magazine for assisting me in my research for this review, and graciously invite you to please join me again next week when I return with another daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensation found in that steaming cesspit known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Seizure (1974)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews