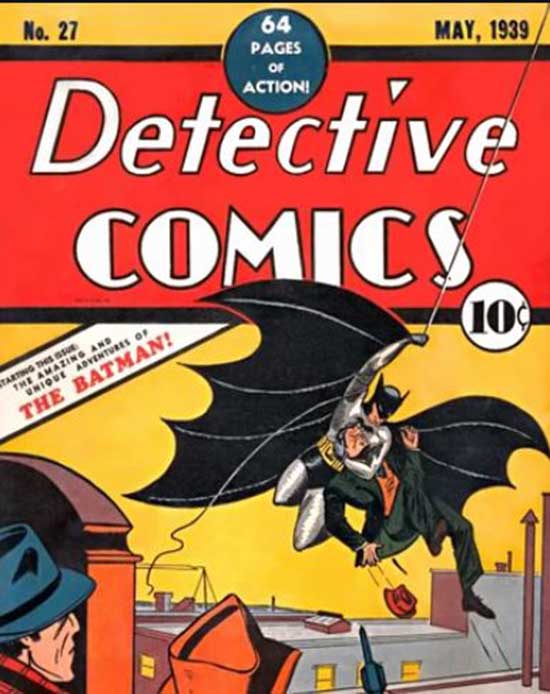

Undoubtedly, Bruce Wayne/Batman has undergone the most drastic change throughout his illustrious and brooding history of perhaps any other major comic book character. Created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger for the March, 1939 issue of Detective Comics, Batman was all but destined for fame as a morose, gothic, morally-ambiguous figure- an image that wouldn’t be fully realized until the mid-‘80s.

Despite the fact that the Dark Knight’s history was rooted in tragedy from day one (the death of his parents at the hands of a mugger pushed to the brink of desperation by the morally-bankrupt and crime-ridden cesspool that is Gotham City), the early Batman stories were leagues away from the character’s current iteration. In his early period, Batman (who was often accompanied by the boisterous and wise-cracking boy wonder, Robin) was comparable to every other lighthearted superhero introduced during the golden age of comics by DC and Marvel- including Captain America, Superman, Spider-Man, and others. In fact, the Detective Comics rendition of Batman was disconcertingly perky- always ready with a cheeky pun or witty retort. In other words, tailor-made for the kiddies (who, in all fairness, were the primary consumers of superhero comics before the advent of adult-oriented storytelling within the art form). The early image of Batman was heavily reinforced by the ‘60s TV sitcom starring Adam West, whose kitschy antics kept young audiences entertained from 1966-68. The character established by Detective Comics and Adam West remained largely intact until 1986, when comics maestro Frank Miller (Sin City, From Hell, 300) gave the Dark Knight a drastic, and lasting, reinvention.

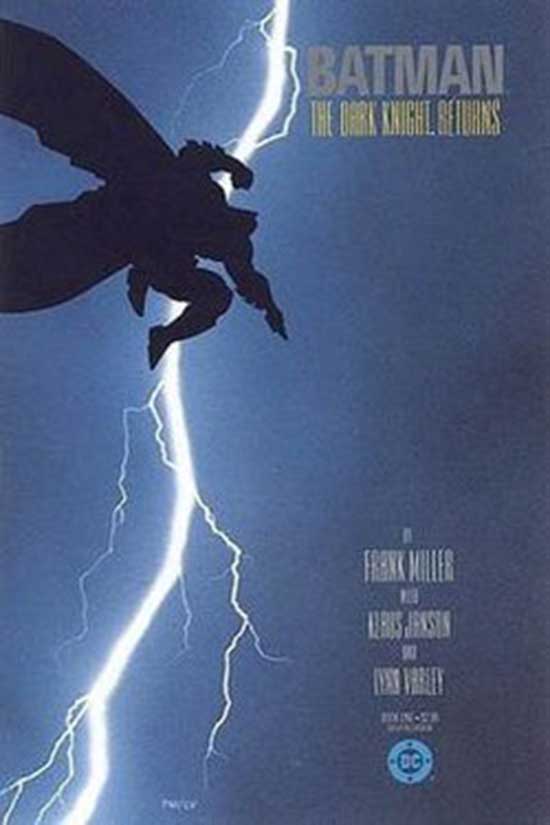

When The Dark Knight Returns hit shelves in 1986, Frank Miller’s landmark miniseries presented the world with a darker, tougher, and infinitely more complex Batman than had thus far graced the pages of D.C. In Miller’s futuristic, steampunk-inspired world, Batman was reestablished as a cynical, aging vigilante who spent his nights crashing a massive tank (Miller’s interpretation of the “Batmobile” here would be co-opted by just about every subsequent writer going forward, standing in sharp contrast to the character’s previously fun and unassuming convertible) through walls and using his hardened, musclebound body as a weapon against Gotham’s criminal underworld. Speaking of Gotham, Miller’s take on what is perhaps pop culture’s most iconic fictional city, left a permanent impression.

Instead of remaining a proxy for New York or Chicago, under Miller’s direction, Gotham became a dirty, funereal dystopia: a cross between the futuristic rendition of Los Angeles seen in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and the surreal, gothic hellscapes of Robert Wiene’s silent horror film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). In the years that followed, some of the Dark Knight’s most accomplished artists and storytellers took the forward-thinking blueprint established by Miller and piled on additional gloomy influences ranging from neo-noir, gothic romance, and psychological horror.

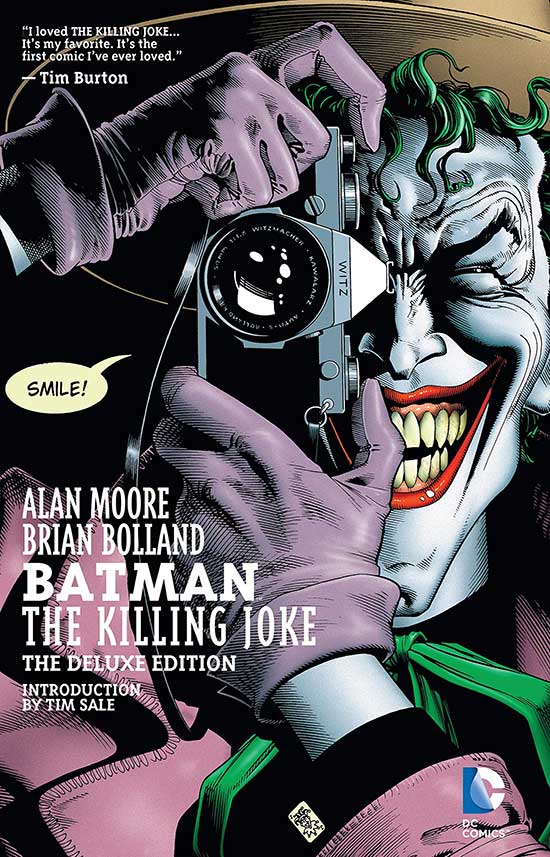

By the tail end of the ‘80s, such macabre sensibilities were bolstered by the iconic narratives of The Killing Joke (written by Alan Moore of Watchmen and V for Vendetta fame) and Jim Starlin and Jim Aparo’s A Death in the Family, which saw the death of Jason Todd, the second Robin, at the hands of the Joker. For those unfamiliar with Batman’s comic book trajectory, it was Tim Burton’s whimsically gloomy 1989 film adaptation Batman, that would forever imprint the Dark Knight’s new, gothic persona into the public consciousness. Burton’s sequel, Batman Returns (1992), pushed the macabre elements even further into decadent, Bava-esque territory. And as Burton’s cinematic adaptations gained traction, another gifted artist was leaving his lasting imprint on Batman. That artist was Scottish writer Grant Morrison.

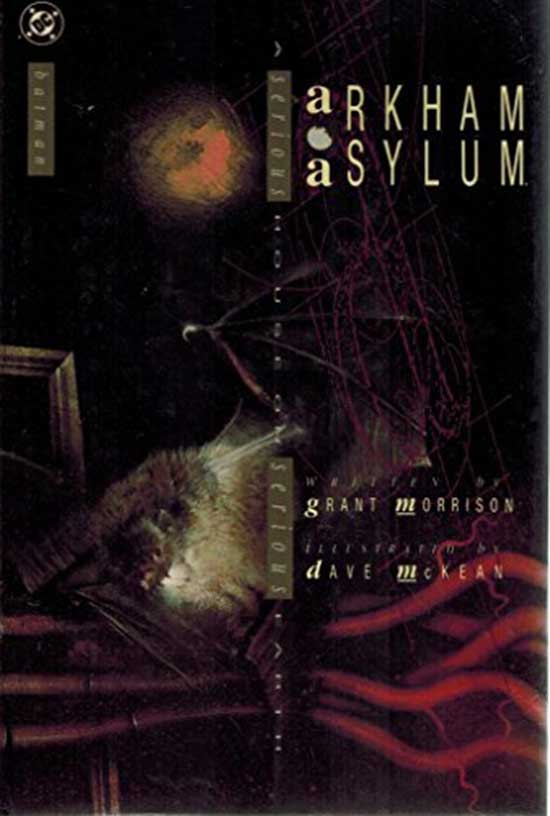

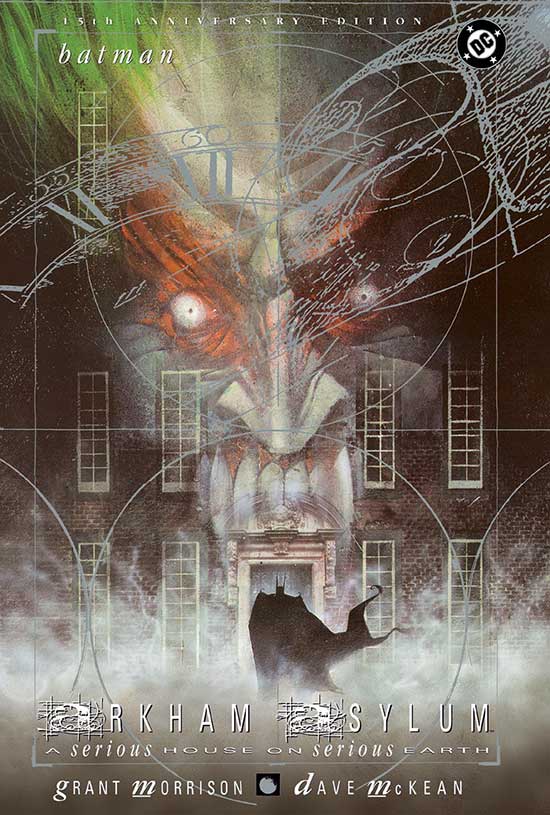

With his masterful narrative skill, Morrison teamed with painter/artist Dave McKean (responsible for the images accompanying Neil Gaiman’s iconic, goth-beloved series The Sandman) for what is perhaps the darkest and most twisted entry in the entire Dark Knight canon: Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989).

Pairing Morrison’s gothic storytelling with McKean’s truly nightmarish, minimalistic art style, Arkham Asylum fleshed out the titular location (culling its name from the world of H.P. Lovecraft), whilst providing several members of Batman’s infamous rogue’s gallery with some truly unsettling makeovers, including Joker, Two-Face, and Killer Croc. A Serious House on Serious Earth is proof-positive that Morrison sits comfortably amongst the pantheon of Batman’s chief modern architects, as important to the character’s reinterpretation as Frank Miller or Alan Moore.

A Serious House on Serious Earth additionally succeeded in adding a new dimension to the Batman mythos: gothic horror. As opposed to the happy-go-lucky, kitsch Batman of old or the futuristic steampunk figure of the Frank Miller contributions, Arkham Asylum presented- through both its storytelling and its sepulchral art style- a world akin to Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, or H.P. Lovecraft. A world in which Morrison and McKean’s tortured protagonist is forced to confront the horrifying reality of the unsettling parallels between himself of his greatest nemeses. In addition to Poe, Lovecraft, and Hawthorne, Arkham Asylum shares numerous commonalities with Dante’s Inferno in its exploratory, meandering story structure. Indeed, throughout the narrative, as the Dark Knight wanders the shadowed, twisted halls of Arkham, he ponders what inkling of mental stability separates himself from the super criminals he’s dedicated his career to capturing and confining to such a sordid locale. Despite its status as a psychiatric institute, Morrison and McKean’s Arkham seems far and away from a place of healing- functioning more as a sort of hellish purgatory for Gotham’s least savory denizens.

Following a visual masterpiece such as Arkham Asylum was never going to be an easy task, but Morrison nonetheless continued to bring his gloomy sensibilities to Batman with the aptly titled Batman: Gothic in 1990. Released less than a year after Tim Burton’s original film hit screens, this short-but-sweet Dark Knight tale follows Batman in his investigation of a murder mystery that takes a Faustian, supernatural turn by its conclusion. Reading like D.C.’s answer to Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw or Hawthorne’s The House of Seven Gables, Batman: Gothic is nothing less than a classic gothic novel translated to comic book form. In case there were any doubt, several of its pages are set within the decadent, tried-and-true gothic locales of cathedrals, abandoned underground dwellings, and by its conclusion: an ancient haunted castle.

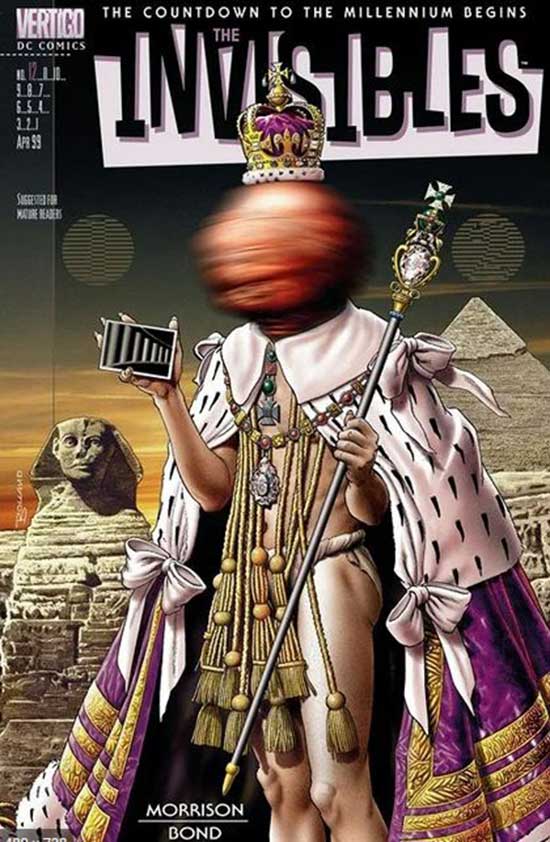

Essential reading for any Batman fan, Gothic leaves no doubt as to why the Caped Crusader occupies the all-too-prestigious role as goth culture’s favorite “superhero”. Morrison’s work continued along other avenues throughout the ‘90s, quite prolifically: Bible John- A Forensic Meditation (1991) examines the motivations of the still-unidentified Scottish “Bible John” serial killer and was favorably compared to Alan Moore’s From Hell, and the Vertigo series The Invisibles (1994-2000), which garnered influences from the writings and philosophies of infamous occultist Aleister Crowley and surrealist poet William S. Burroughs (of Naked Lunch fame).

The Invisibles was also credited as a major influence on the Wachowski Brothers’ groundbreaking sci-fi film The Matrix (1999). Additionally, while he spent time away from the Dark Knight, Morrison was nonetheless eager to contribute his talents to Batman’s D.C. brethren in the Justice League. By the 2000s, Morrison even transitioned to Marvel, where he left his indelible stamp on the X-Men (New X-Men, 2001-2004) and the Fantastic Four (Fantastic Four: 1234), whilst continuing to churn out various indie titles for D.C./Vertigo.

In 2006, as he returned to the Batman universe for the Batman and Son series (which saw Bruce Wayne’s son Damian taking up the mantle of Robin), Morrison received at least a fraction of his just due as a comic book architect with the #2 spot on Comic Book Resource’s list of the greatest comic book authors of all time, right behind Alan Moore. Morrison continued his return to Batman into the 2010s with the revamped Batman and Robin series (2009-2011), in which Bruce Wayne is presumed dead, leading Dick Grayson (the original Robin, for those not in the know) to take up the mantle of the cowl with Damian Wayne’s Robin at his side.

The Batman and Robin arc, it should be noted, followed Morrison’s work on Batman: R.I.P. (2008), in which Batman survives being buried alive in a shallow grave, and the Superman crossover Final Crisis (2008-2009), which led to Tony S. Daniel’s Battle for the Cowl (2009), in which the original Batman supposedly perishes at the hands of cosmic threat Darkseid. Batman R.I.P. in particular, shared numerous aesthetic similarities with Morrison’s classic Arkham Asylum, and is inarguably one of the darkest Batman runs of them all. Morrison’s omnipresent influence over the Batman universe was compounded further by his work on Batman Inc. and The New 52, which successfully launched D.C. into the future.

Although Morrison wasn’t involved with this particular storyline, one of the defining yarns of the New 52 era was Joker: Death of the Family (2012-2013) which is highly recommended for fans of the disturbing, horror-influenced side of the Batman universe. In a particularly sadistic series of events, the Joker returns to deprive Batman of everything and everyone he values, particularly the members of his extended “Bat family”: Alfred, Robin, Nightwing, Batgirl, Red Hood, etc. What’s particularly startling about this Joker is that he wears his surgically-removed face like a mask (and in a similar manner to Leatherface of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre [1974]) in order to further remove himself from his own humanity.

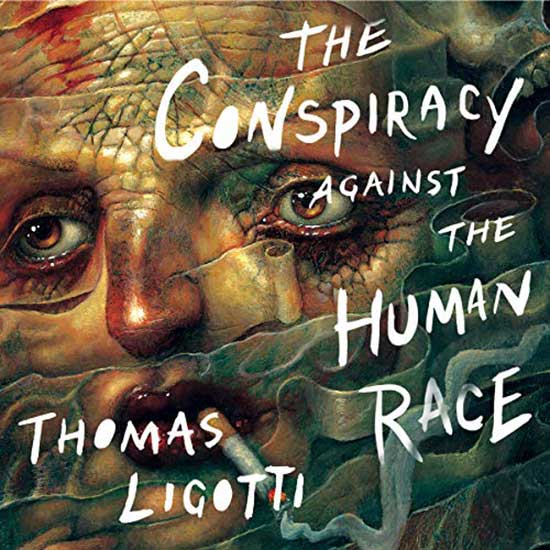

Morrison always flirted with horror imagery and atmospheres throughout his career, particularly when it came to his take on the Dark Knight. However, the legendary writer dived headfirst into the genre with the Legendary Comics series Annihilator (2014), based of the writings of dark philosopher and horror author Thomas Ligotti (The Conspiracy Against the Human Race) which dealt with themes of satanism and Lovecraftian horror, and the marvelously gruesome limited series Nameless (2015). If H.P. Lovecraft had lived long enough to scribe his own comics series, it would undoubtedly read something like Nameless, which involves a group of astronauts attempting to intercept a massive asteroid before it destroys planet Earth. In the process, the crew falls under a cosmic, occult influence which forces them to question both their sanity and the nature of reality. For Lovecraft aficionados, as well as fans of the underrated 1997 sci-fi/horror film Event Horizon and the survival horror video game series Dead Space (2008, 2011, 2013), Nameless comes highly recommended.

As I write these words, Morrison continues with his contributions to Green Lantern for D.C., as well as being in talks for numerous TV adaptations of his comic book work and having a novella in the works. But, if he were to decide on the spur of the moment to retire his pen for good, Morrison would always be remembered as one of the greatest (if not the greatest) comic book creators of all time. An indispensable architect of the Batman universe whose pervasive and lasting influence lives on in the works of subsequent artists, writers, animators, and filmmakers, it’s difficult to imagine the Caped Crusader we’d have today if not for Grant Morrison’s contributions.

With splendid works like Arkham Asylum, Batman: Gothic, Annihilator, Batman R.I.P., and Nameless, Morrison ensured that the influence of gothic literature, H.P. Lovecraft, lurid philosophy, and sci-fi innovation had a place within the pages of comic books. An industry once derided for being mere “kiddie fare” has now, thanks in large part to writers like Morrison, blossomed into a genuine art form that manages to increase in sophistication and storytelling technique as the comic books move further into the future. And speaking of the future, we should all hope that Grant Morrison will be there to see our favorite characters on their paths forward in the years ahead.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews