“Professor Bernard Quatermass is in charge of a manned rocket mission that has gone awry. They lost contact with the spaceship at one point and have no idea how far into space it may have traveled. When the rocket crash lands in a farmer’s field they find that only one of the three occupants, Victor Carroon, is on board; the others have simply vanished. Slowly, the surviving astronaut begins to transform into a hideous creature and Quatermass realises that Carroon may have been infected by an alien being. When Carroon escapes from the hospital with the help of his unsuspecting wife, the authorities race to destroy it before it multiplies.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

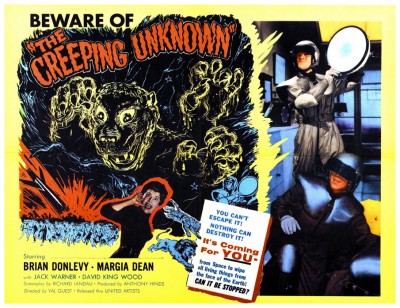

British genre films in the fifties followed a path similar to their American cousins, though on a much smaller scale. During the first half of the decade they tended to reflect the underlying fears of the Cold War, and it was during this period that the better films were produced. Then, from 1956 onwards, the cycle degenerated into ever cheaper and more perfunctory variations on the monster theme. Like most American genre films of the mid-fifties, British genre films were also taken over by monsters at the expense of other important elements. The film that did the most to establish this trend in Britain was The Quatermass Xperiment aka The Creeping Unknown (1955) made by Hammer Films. It was based on a BBC television serial written by Nigel Kneale, a screenwriter with an uncanny knack for combining contemporary science fiction themes with both mythology and traditional elements of the supernatural to produce stories that tend to bypass the forebrain and work directly on unconscious fears – a master of creating a state of unease.

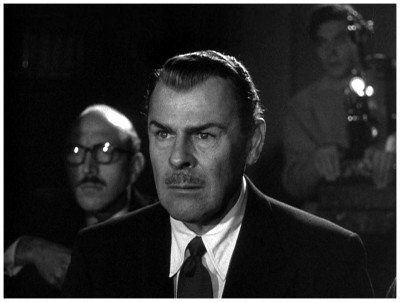

It was Hammer’s usual method to adapt proven successes from both radio and television and, as the first Quatermass serial had been a nationwide success in 1953, they naturally chose to make it into a film. Their budget was as small as ever, but they did have the advantage of an American distribution deal. This meant that a minor or fading American star had to be included in the cast to ensure that American audiences would have some kind of emotional focus and not be alienated by all the strange accents. Chosen for this task was Brian Donlevy, a former Hollywood leading man and character actor, who played the central role of Professor Bernard Quatermass. The American distributor was Robert Lippert, who had already been involved in a number of cheap exploitation films such as Rocketship XM (1950) and Project Moonbase (1953). The strange spelling of the title was a gimmick in itself. The big ‘X’ in the word ‘Xperiment’ referred to the ‘X’ censor’s certificate they correctly expected to be given for the film’s horror content.

It was Hammer’s usual method to adapt proven successes from both radio and television and, as the first Quatermass serial had been a nationwide success in 1953, they naturally chose to make it into a film. Their budget was as small as ever, but they did have the advantage of an American distribution deal. This meant that a minor or fading American star had to be included in the cast to ensure that American audiences would have some kind of emotional focus and not be alienated by all the strange accents. Chosen for this task was Brian Donlevy, a former Hollywood leading man and character actor, who played the central role of Professor Bernard Quatermass. The American distributor was Robert Lippert, who had already been involved in a number of cheap exploitation films such as Rocketship XM (1950) and Project Moonbase (1953). The strange spelling of the title was a gimmick in itself. The big ‘X’ in the word ‘Xperiment’ referred to the ‘X’ censor’s certificate they correctly expected to be given for the film’s horror content.

The film begins with a rocketship hurtling out of the night sky and burying itself nose-first in a field behind a farm house. Police, fire brigade and sightseers quickly arrive at the scene of the crash, among them Professor Quatermass, the man in charge of Britain’s first attempted flight into space. He takes control and orders the firemen to aim their hoses around the hatchway so that the astronauts will have some protection from the heat of the ship’s hull when they emerge. The door is opened by remote control and a figure slowly emerges, one of the three astronauts inside the ship. He stumbles and falls, and is quickly placed on a stretcher and taken to an ambulance. Quatermass and the others find no sign of the other two astronauts, but they do find their spacesuits. However, both of them are empty, yet linked up in such a way as to suggest that the men disappeared while wearing them.

The film begins with a rocketship hurtling out of the night sky and burying itself nose-first in a field behind a farm house. Police, fire brigade and sightseers quickly arrive at the scene of the crash, among them Professor Quatermass, the man in charge of Britain’s first attempted flight into space. He takes control and orders the firemen to aim their hoses around the hatchway so that the astronauts will have some protection from the heat of the ship’s hull when they emerge. The door is opened by remote control and a figure slowly emerges, one of the three astronauts inside the ship. He stumbles and falls, and is quickly placed on a stretcher and taken to an ambulance. Quatermass and the others find no sign of the other two astronauts, but they do find their spacesuits. However, both of them are empty, yet linked up in such a way as to suggest that the men disappeared while wearing them.

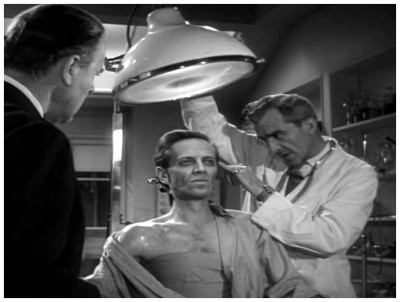

After this effective beginning, the film continues its build-up of unease. The surviving astronaut, Victor Carroon (Richard Wordsworth), is apparently in the grip of a strange disease. After saying just two words (“Help me!”) he can no longer communicate with anyone, even his wife Judith (Margia Dean), and his skin is beginning to undergo a transformation. Even his bone structure is changing and, in the hospital, the process of change enters a new phase – he absorbs a cactus plant into his arm which takes on the appearance of a large shapeless mass covered with spikes. He escapes from the hospital and staggers off into the night, an emaciated tortured figure who is still partly human and terrified by what he knows he is becoming. When he is finally tracked down in Westminster Abbey, the metamorphosis is complete and he has become a large pulsating octopus-like creature, totally unrecognisable as a human being. Quatermass arranges to have him electrocuted before he can discharge a number of spores into the air. Soon after the creature’s dying screams are heard, Quatermass announces he’s going to launch another rocket as soon as possible.

After this effective beginning, the film continues its build-up of unease. The surviving astronaut, Victor Carroon (Richard Wordsworth), is apparently in the grip of a strange disease. After saying just two words (“Help me!”) he can no longer communicate with anyone, even his wife Judith (Margia Dean), and his skin is beginning to undergo a transformation. Even his bone structure is changing and, in the hospital, the process of change enters a new phase – he absorbs a cactus plant into his arm which takes on the appearance of a large shapeless mass covered with spikes. He escapes from the hospital and staggers off into the night, an emaciated tortured figure who is still partly human and terrified by what he knows he is becoming. When he is finally tracked down in Westminster Abbey, the metamorphosis is complete and he has become a large pulsating octopus-like creature, totally unrecognisable as a human being. Quatermass arranges to have him electrocuted before he can discharge a number of spores into the air. Soon after the creature’s dying screams are heard, Quatermass announces he’s going to launch another rocket as soon as possible.

The subtext – that science can reduce men to beasts – was crude enough, though rendered more compelling by the fact that the supposed hero, Professor Quatermass, is unsympathetically hard-headed and fully prepared to continue the space program no matter what the cost in human suffering. The special effects are not terribly special, though Les Bowie – Hammer’s top effects man for many years – performed miracles on the tiny budget, but Wordsworth’s shambling pathetic performance is memorable, and the film put the studio back on its feet and encouraged it to follow-on with many more man-into-monster movies, including the direct sequels Quatermass II (1957) and Quatermass And The Pit (1967).

The subtext – that science can reduce men to beasts – was crude enough, though rendered more compelling by the fact that the supposed hero, Professor Quatermass, is unsympathetically hard-headed and fully prepared to continue the space program no matter what the cost in human suffering. The special effects are not terribly special, though Les Bowie – Hammer’s top effects man for many years – performed miracles on the tiny budget, but Wordsworth’s shambling pathetic performance is memorable, and the film put the studio back on its feet and encouraged it to follow-on with many more man-into-monster movies, including the direct sequels Quatermass II (1957) and Quatermass And The Pit (1967).

The Quatermass Xperiment was directed by Val Guest, a former actor turned journalist who was active in the British film industry as a writer, director and producer since the thirties. I had the opportunity to talk to Mr. Guest when we met on the set of the 1976 television show Space 1999: “I got involved with Quatermass through Tony Hinds, who was then a producer at Hammer. I was just going on holiday to Tangier and he called me and asked if I would read a breakdown of a thing called The Quatermass Experiment which had been a great success on television. I hadn’t seen the serial at all because I’d been away, and I had one or two other scripts to read, so I went off to Tangier leaving Hammer’s story breakdown on my bedside table. When I came back I read it through and I said to myself, ‘I don’t really I want to do this. It may have been a big TV success but I can’t see what there is in this.’ So I left it and then my wife read it and said, ‘What are you going to do about this Quatermass thing?’ I said, ‘I don’t think I want to do it,’ and she cried, ‘You’re mad! Do it. Do something different!’ So that’s how I came to do it. I very nearly didn’t.”

The Quatermass Xperiment was directed by Val Guest, a former actor turned journalist who was active in the British film industry as a writer, director and producer since the thirties. I had the opportunity to talk to Mr. Guest when we met on the set of the 1976 television show Space 1999: “I got involved with Quatermass through Tony Hinds, who was then a producer at Hammer. I was just going on holiday to Tangier and he called me and asked if I would read a breakdown of a thing called The Quatermass Experiment which had been a great success on television. I hadn’t seen the serial at all because I’d been away, and I had one or two other scripts to read, so I went off to Tangier leaving Hammer’s story breakdown on my bedside table. When I came back I read it through and I said to myself, ‘I don’t really I want to do this. It may have been a big TV success but I can’t see what there is in this.’ So I left it and then my wife read it and said, ‘What are you going to do about this Quatermass thing?’ I said, ‘I don’t think I want to do it,’ and she cried, ‘You’re mad! Do it. Do something different!’ So that’s how I came to do it. I very nearly didn’t.”

Since Hammer already had Kneale’s original BBC scripts broken down and condensed into a treatment, Guest didn’t go through the scripts himself, but always referred to them when wanting to check up on some of the technical information. “The film, of course, was made on a very small budget, and there are always problems when you’re working on a small budget, but that sort of situation can be good for you because it makes you think. You dig a lot deeper into your creative recesses to see what you can pull out of the hat. The rocketship in the opening sequence, for instance, we built in the grounds of Bray Studio. It looked enormous but it wasn’t really. We only built the bottom part of it, the rest was matted on afterwards. I used wide-angle lenses on it most of the time to give it a feeling of vastness.”

Since Hammer already had Kneale’s original BBC scripts broken down and condensed into a treatment, Guest didn’t go through the scripts himself, but always referred to them when wanting to check up on some of the technical information. “The film, of course, was made on a very small budget, and there are always problems when you’re working on a small budget, but that sort of situation can be good for you because it makes you think. You dig a lot deeper into your creative recesses to see what you can pull out of the hat. The rocketship in the opening sequence, for instance, we built in the grounds of Bray Studio. It looked enormous but it wasn’t really. We only built the bottom part of it, the rest was matted on afterwards. I used wide-angle lenses on it most of the time to give it a feeling of vastness.”

It was much the same with Westminster Abbey in the final sequences. Hammer built that particular set in what is called the large stage at Bray, but it’s actually quite small. Again they only built the bottom part of the set and matted the rest on later. The exterior of the Abbey entrance was also built on the Bray lot and again Guest used as wide a lens as possible to shoot it. There were no shots of the real Abbey in the film at all. There were quite a few attempts to construct the monster that appeared in the climax, and eventually it ended up being made mostly out of pieces of tripe (cow stomach) as well as a rubber solution, which was all the work of Les Bowie, Hammer’s top special effects technician. Guest didn’t have much to do with the filming of the creature as it was all shot in Bowie’s effects studio.

It was much the same with Westminster Abbey in the final sequences. Hammer built that particular set in what is called the large stage at Bray, but it’s actually quite small. Again they only built the bottom part of the set and matted the rest on later. The exterior of the Abbey entrance was also built on the Bray lot and again Guest used as wide a lens as possible to shoot it. There were no shots of the real Abbey in the film at all. There were quite a few attempts to construct the monster that appeared in the climax, and eventually it ended up being made mostly out of pieces of tripe (cow stomach) as well as a rubber solution, which was all the work of Les Bowie, Hammer’s top special effects technician. Guest didn’t have much to do with the filming of the creature as it was all shot in Bowie’s effects studio.

“I was the one who cast Richard Wordsworth as the infected astronaut. He was a very good character actor and he had the right sort of face for the part. He gave an incredible performance, I thought. Funnily enough, whenever I see Dickie Wordsworth now he always says that it was thanks to me that, in his very first film appearance, he had to get sprayed in the face by seven fire-hoses. I used him in another Hammer film, Camp On Blood Island (1958) because, again, he looked right with his thin, gaunt appearance. He looked as if he had been in a Japanese prison camp. I don’t know why his career never took off after Quatermass because he was so good in that film. Particularly his scene with the little girl – who was Jane Asher – by the canal.”

“I was the one who cast Richard Wordsworth as the infected astronaut. He was a very good character actor and he had the right sort of face for the part. He gave an incredible performance, I thought. Funnily enough, whenever I see Dickie Wordsworth now he always says that it was thanks to me that, in his very first film appearance, he had to get sprayed in the face by seven fire-hoses. I used him in another Hammer film, Camp On Blood Island (1958) because, again, he looked right with his thin, gaunt appearance. He looked as if he had been in a Japanese prison camp. I don’t know why his career never took off after Quatermass because he was so good in that film. Particularly his scene with the little girl – who was Jane Asher – by the canal.”

“The whole film was a very enjoyable experience. There was a lovely family atmosphere at Bray and everyone was busting their guts to make it look like the film was made on two shoestrings instead of just one. At the time we had no idea it was going to be an important film in terms of Hammer’s future as a company. It was also personally important for me in that it was my first science fiction picture – I’d done every other kind of picture up to then but never a science fiction one – and it started me thinking in terms of making other science fiction films.” Val Guest later wrote, produced and directed The Day The Earth Caught Fire (1961), but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’d like to profusely thank the British TV Times (24th July 1975) for assisting my research for this article, and invite you to please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with more terror-filled excursions to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

“The whole film was a very enjoyable experience. There was a lovely family atmosphere at Bray and everyone was busting their guts to make it look like the film was made on two shoestrings instead of just one. At the time we had no idea it was going to be an important film in terms of Hammer’s future as a company. It was also personally important for me in that it was my first science fiction picture – I’d done every other kind of picture up to then but never a science fiction one – and it started me thinking in terms of making other science fiction films.” Val Guest later wrote, produced and directed The Day The Earth Caught Fire (1961), but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’d like to profusely thank the British TV Times (24th July 1975) for assisting my research for this article, and invite you to please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with more terror-filled excursions to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews