SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

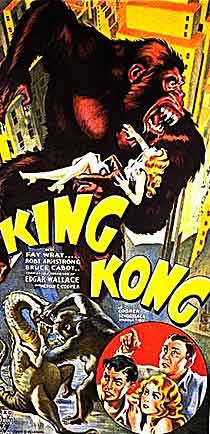

“In 1933, the bold and successful filmmaker Carl Denham travels by ship with a large crew, his friend Jack Driscoll and the starlet Ann Darrow to an unknown island to shoot a movie. The local natives worship a huge gorilla called Kong and they abduct Ann to offer her in a sacrifice to Kong. Jack Driscoll, who is in love with her, Carl Denham, who aims to capture the animal for an exhibition in New York and part of the crew hike into the jungle, where dinosaurs live, trying to rescue Ann. King Kong falls in love for Ann and protects her against the dangers. But the gorilla is captured and brought to New York. In the middle of a show in Broadway, King Kong escapes, bringing panic to the Apple city.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

There had been monsters before King Kong (1933). The dinosaurs in The Lost World (1925), and the creature in Frankenstein (1931) – but he was a deformed man rather than a beast. It was King Kong that set up a matrix for the monster genre in which many monster movies are molded even today. Much has been written about this film, and its epic story has been interpreted in many ways – sexually, politically and racially. It’s so full of striking imagery that it’s easy to see symbolic undertones in almost every frame.

A popular film will often reflect contemporary attitudes and fears without its makers realising it – one of the more popular interpretations is that King Kong represents the American black, a creature who is taken forcibly from his homeland to America where he is exploited in chains but then breaks free and conquers New York (every scene in New York corresponds to a scene on Skull Island), snarling his defiance at the world. Certainly many young American blacks identified with Kong and conversely the film reflected white America’s fear of the black man. Gorillas, as menacing creatures, had been featuring in American films since the early silent days, often in serials and in such films as The Unholy Three (1925 & 1930), The Murders In The Rue Morgue (1914 & 1932) and even Sign Of The Cross (1932). Usually at some point in the story, they threaten a beautiful white girl with ‘a fate worse than death’. King Kong takes this metaphor of sexual threat to its ultimate limit – the film is a treasure-trove of Freudian symbols:

A popular film will often reflect contemporary attitudes and fears without its makers realising it – one of the more popular interpretations is that King Kong represents the American black, a creature who is taken forcibly from his homeland to America where he is exploited in chains but then breaks free and conquers New York (every scene in New York corresponds to a scene on Skull Island), snarling his defiance at the world. Certainly many young American blacks identified with Kong and conversely the film reflected white America’s fear of the black man. Gorillas, as menacing creatures, had been featuring in American films since the early silent days, often in serials and in such films as The Unholy Three (1925 & 1930), The Murders In The Rue Morgue (1914 & 1932) and even Sign Of The Cross (1932). Usually at some point in the story, they threaten a beautiful white girl with ‘a fate worse than death’. King Kong takes this metaphor of sexual threat to its ultimate limit – the film is a treasure-trove of Freudian symbols:

The film begins in the real world, in a dark, cold, Depression-era New York, but from the moment the Venture leaves port we are on a journey through Carl Denham’s subconscious, not unlike the journey taken in the literary classic Heart Of Darkness. Skull (as in ‘cerebral’) Island’s expressionistic landscapes – fertile, overgrown, reptile-infested, cave-filled – is Denham’s fantasised sexual terrain, and Kong is a manifestation of Denham’s subconscious. Denham conjures up Kong as a surrogate to battle Driscoll for Ann’s love and to perform ‘sexually’ (their trip up New York’s tallest phallus) with her when he has never been willing (or able) to have a sexual encounter himself. Although young and virile, Denham has traveled the world with an all-male crew deliberately to avoid intimate liaisons. Kong is Denham’s bestial side, his alter ego. Kong is evidence of Denham’s desperate need to possess Ann, his birth is the result of Denham’s continuing to suppress his sexual/romantic side even when he is immediately attracted to Ann. That Denham and Kong are rarely seen in the same shot indicates that Kong is being directed by an external force, namely Denham’s subconscious. When they do confront each other, Denham tries to restrain Kong (his bestial side) with a great wall, bombs and chains. When Kong breaks the chains, Denham can no longer control his sexual urges toward Ann. Significantly, we never seem them together until Kong is dead. Denham’s famous words “It was beauty killed the beast” makes sense if he’s referring to the bestial side of himself. If Freud hadn’t existed it would have been necessary to invent him after King Kong!

The film begins in the real world, in a dark, cold, Depression-era New York, but from the moment the Venture leaves port we are on a journey through Carl Denham’s subconscious, not unlike the journey taken in the literary classic Heart Of Darkness. Skull (as in ‘cerebral’) Island’s expressionistic landscapes – fertile, overgrown, reptile-infested, cave-filled – is Denham’s fantasised sexual terrain, and Kong is a manifestation of Denham’s subconscious. Denham conjures up Kong as a surrogate to battle Driscoll for Ann’s love and to perform ‘sexually’ (their trip up New York’s tallest phallus) with her when he has never been willing (or able) to have a sexual encounter himself. Although young and virile, Denham has traveled the world with an all-male crew deliberately to avoid intimate liaisons. Kong is Denham’s bestial side, his alter ego. Kong is evidence of Denham’s desperate need to possess Ann, his birth is the result of Denham’s continuing to suppress his sexual/romantic side even when he is immediately attracted to Ann. That Denham and Kong are rarely seen in the same shot indicates that Kong is being directed by an external force, namely Denham’s subconscious. When they do confront each other, Denham tries to restrain Kong (his bestial side) with a great wall, bombs and chains. When Kong breaks the chains, Denham can no longer control his sexual urges toward Ann. Significantly, we never seem them together until Kong is dead. Denham’s famous words “It was beauty killed the beast” makes sense if he’s referring to the bestial side of himself. If Freud hadn’t existed it would have been necessary to invent him after King Kong!

There’s still controversy over exactly who contributed what to the story of King Kong. Various people receive an actual credit in the film: Ruth Rose (Ernest B. Schoedsack’s wife) and James A. Creelman – who also wrote the screenplay for Merian C. Cooper and Schoedsack’s The Most Dangerous Game (1932) – are both credited with the screenplay, while Cooper himself and Edgar Wallace are credited with conceiving the idea, though it’s doubtful whether Wallace had anything to do with the original idea or the script, since the famous English novelist and playwright passed away soon after arriving in Hollywood. Also credited was Horace McCoy – best known for his novel They Shoot Horses Don’t They? (1969) – who worked as Creelman’s assistant on the film. But the one person who didn’t receive any credit for any of the story elements was Willis O’Brien himself, yet so many of the action sequences must first have been conceived by him purely in terms of animation. Much of the structure of the film, and many of its set-pieces came from O’Brien’s storyboards. Many things in King Kong can be traced to earlier O’Brien projects such as The Lost World (1925) and his unfinished film Creation. For instance, the idea of a giant prehistoric monster running amuck in a modern city comes from O’Brien’s version of The Lost World, as does the log spanning a vast chasm which is then dislodged by a monster (an image used in both The Lost World and Creation), and the sequence where Kong reels in Ann Darrow and Driscoll as they attempt to climb down a vine is an elaboration of a similar sequence in The Lost World. Without a doubt, O’Brien contributed more to the overall structure of King Kong than he has been given credit for.

There’s still controversy over exactly who contributed what to the story of King Kong. Various people receive an actual credit in the film: Ruth Rose (Ernest B. Schoedsack’s wife) and James A. Creelman – who also wrote the screenplay for Merian C. Cooper and Schoedsack’s The Most Dangerous Game (1932) – are both credited with the screenplay, while Cooper himself and Edgar Wallace are credited with conceiving the idea, though it’s doubtful whether Wallace had anything to do with the original idea or the script, since the famous English novelist and playwright passed away soon after arriving in Hollywood. Also credited was Horace McCoy – best known for his novel They Shoot Horses Don’t They? (1969) – who worked as Creelman’s assistant on the film. But the one person who didn’t receive any credit for any of the story elements was Willis O’Brien himself, yet so many of the action sequences must first have been conceived by him purely in terms of animation. Much of the structure of the film, and many of its set-pieces came from O’Brien’s storyboards. Many things in King Kong can be traced to earlier O’Brien projects such as The Lost World (1925) and his unfinished film Creation. For instance, the idea of a giant prehistoric monster running amuck in a modern city comes from O’Brien’s version of The Lost World, as does the log spanning a vast chasm which is then dislodged by a monster (an image used in both The Lost World and Creation), and the sequence where Kong reels in Ann Darrow and Driscoll as they attempt to climb down a vine is an elaboration of a similar sequence in The Lost World. Without a doubt, O’Brien contributed more to the overall structure of King Kong than he has been given credit for.

But everyone has always agreed that the film represents O’Brien’s finest achievement in the area of model animation. His models merge perfectly with a story of almost epic proportions, with the result that the special effects, while vitally important, don’t take over the film to the extent where the story becomes a mere appendage (as so often happens with films built around model animation). In King Kong the story itself is always the dominant element.

But everyone has always agreed that the film represents O’Brien’s finest achievement in the area of model animation. His models merge perfectly with a story of almost epic proportions, with the result that the special effects, while vitally important, don’t take over the film to the extent where the story becomes a mere appendage (as so often happens with films built around model animation). In King Kong the story itself is always the dominant element.

I’m sure I don’t have to mention the gazillion or so giant monster movies inspired by the original King Kong, and I certainly don’t have to mention the atrocious 1976 remake nor the wonderfully self-indulgent Peter Jackson film – and I mean that in the nicest possible way – Sir Peter’s excellent 2005 version was also pure indulgence for me and most fans of the original 1933 masterpiece. But that’s another story for another time. It’s terribly important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope specifically said that unless you read all our remaining film reviews, all life on Earth would cease to exist! Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but it sounded so convincing, I feel you’d best not take the risk. So have a relaxing weekend and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

I’m sure I don’t have to mention the gazillion or so giant monster movies inspired by the original King Kong, and I certainly don’t have to mention the atrocious 1976 remake nor the wonderfully self-indulgent Peter Jackson film – and I mean that in the nicest possible way – Sir Peter’s excellent 2005 version was also pure indulgence for me and most fans of the original 1933 masterpiece. But that’s another story for another time. It’s terribly important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope specifically said that unless you read all our remaining film reviews, all life on Earth would cease to exist! Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but it sounded so convincing, I feel you’d best not take the risk. So have a relaxing weekend and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews