SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

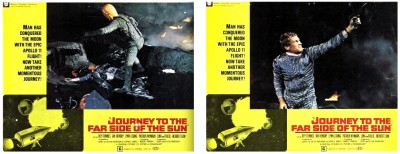

“A planet is discovered in the same orbit as Earth’s but is located on the exact opposite side of the sun, making it not visible from Earth. The European Space Exploration Council decide to send American astronaut Glenn Ross and British scientist John Kane via spaceship to explore the other planet. After a disastrous crash-landing Ross awakes to learn that Kane lies near death and that they apparently have returned to Earth, as evidenced by the presence of the Council director and his staff. Released to the custody of his wife, he soon learns things are not as they seem.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Most of the science fiction films that followed 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) were something of an anti-climax, particularly those that involved space travel. The fifth film in the James Bond franchise, You Only Live Twice (1967), suddenly looked awfully weak during its outer space sequences, the special effects looking rather amateur compared to those of Kubrick’s masterpiece. Also something of a dud was Marooned (1969), a space soap opera directed by John Sturges, who was best known for westerns like The Magnificent Seven (1960). Just as dull was the similar film Countdown (1976), probably director Robert Altman’s least effort, which had astronaut James Caan stranded alone on the moon.

Superior in the area of special effects was a British film called Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun (1969), better known as Doppelgänger in some countries, directed by classic Twilight Zone veteran Robert Parrish, one of six directors to work on the shambles known as Casino Royale (1967). The script was a mixture of sheer pretentiousness and pseudo-science at its most illogical. It was written by husband-and-wife producers Gerry Anderson and Sylvia Anderson (regarded by many as the British equivalents of Hollywood producer Irwin Allen), and was based on the old idea of a planet on the opposite side of the sun which remains undetected by Earth astronomers. Unfortunately, the Andersons lose control of the plot along the way, and the film degenerates into utter confusion.

Superior in the area of special effects was a British film called Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun (1969), better known as Doppelgänger in some countries, directed by classic Twilight Zone veteran Robert Parrish, one of six directors to work on the shambles known as Casino Royale (1967). The script was a mixture of sheer pretentiousness and pseudo-science at its most illogical. It was written by husband-and-wife producers Gerry Anderson and Sylvia Anderson (regarded by many as the British equivalents of Hollywood producer Irwin Allen), and was based on the old idea of a planet on the opposite side of the sun which remains undetected by Earth astronomers. Unfortunately, the Andersons lose control of the plot along the way, and the film degenerates into utter confusion.

To keep us entertained during this tragical mystery tour we are accompanied by some of the more interesting character actors of the era. Along with Gerry Anderson regulars George Sewell, Ed Bishop and Philip Madoc, we have:

To keep us entertained during this tragical mystery tour we are accompanied by some of the more interesting character actors of the era. Along with Gerry Anderson regulars George Sewell, Ed Bishop and Philip Madoc, we have:

* Herbert Lom has played the token European in more than a hundred roles over an amazing seven decades, in films such as The Ladykillers (1955), I Aim At The Stars (1960), Mysterious Island (1961), The Phantom Of The Opera (1962) and A Shot In The Dark (1964), after which he became forever known as Chief Inspector Dreyfuss.

* Ian Hendry may not have Emma Peel’s legs, but he was John Steed’s first companion in The Avengers, a spin-off from Police Surgeon. Other notable films include Theatre Of Blood (1973) and Captain Kronos Vampire Hunter (1974).

* Roy Thinnes became internationally famous for being one of the most paranoid characters in fiction, David Vincent, in the cult television show The Invaders and, two decades later, in The X-Files.

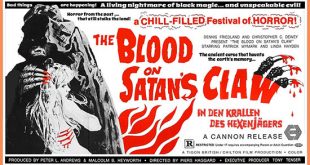

* Patrick Wymark could be found in Children Of The Damned (1964), Repulsion (1965), The Skull (1965), The Psychopath (1966), Witchfinder General (1968) and Blood On Satan’s Claw (1971).

* Nicholas Courtney gets a couple of lines as a nameless technician, just long enough to recognise him as Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart from Doctor Who.

The incredible special effects were supervised by miniature model-making maestro Derek Meddings, who had been in charge of the effects in Anderson’s popular puppet television series Thunderbirds. I was lucky enough to make Mr. Meddings acquaintance on the set of Spies Like Us (1985): “We had to simulate a rocket take-off from Cape Canaveral because we couldn’t use existing footage, as our rocket was supposed look more futuristic than any existing rocket and also much bigger. So we had to build a miniature Cape Canaveral in the studio, which we did, and it was very successful. So was the rocket take-off itself – for that we built a model six feet high, and all around it we had the miniature launch area, including the gantry, the tower and other buildings as well as little vehicles running around. Later in the film we had to wreck all that for the sequence where the rocket comes back, out of control, and crashes into the launch site.”

The incredible special effects were supervised by miniature model-making maestro Derek Meddings, who had been in charge of the effects in Anderson’s popular puppet television series Thunderbirds. I was lucky enough to make Mr. Meddings acquaintance on the set of Spies Like Us (1985): “We had to simulate a rocket take-off from Cape Canaveral because we couldn’t use existing footage, as our rocket was supposed look more futuristic than any existing rocket and also much bigger. So we had to build a miniature Cape Canaveral in the studio, which we did, and it was very successful. So was the rocket take-off itself – for that we built a model six feet high, and all around it we had the miniature launch area, including the gantry, the tower and other buildings as well as little vehicles running around. Later in the film we had to wreck all that for the sequence where the rocket comes back, out of control, and crashes into the launch site.”

“It was quite a large miniature because we had to be able to track right through it with a very low camera, between buildings and so on, to provide the back-projection footage for scenes where the characters are supposed to be in vehicles driving through the base. I think we spent over a hundred thousand pounds on the effects in that film. At the time, the company was riding high because of the success of Thunderbirds, etc. so it was able to get the finance for whatever it wanted to do. We were put up to be nominated for an effects Oscar that year but, unfortunately, didn’t even get a nomination. The film that won the effects Oscar was Marooned!”

“It was quite a large miniature because we had to be able to track right through it with a very low camera, between buildings and so on, to provide the back-projection footage for scenes where the characters are supposed to be in vehicles driving through the base. I think we spent over a hundred thousand pounds on the effects in that film. At the time, the company was riding high because of the success of Thunderbirds, etc. so it was able to get the finance for whatever it wanted to do. We were put up to be nominated for an effects Oscar that year but, unfortunately, didn’t even get a nomination. The film that won the effects Oscar was Marooned!”

Neither Marooned nor Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun was a great box-office success, and the blame was put chiefly on the real moon landing that took place that very same year, an event that tended to make the cinema’s space age activities look rather out-of-date. The same excuse was used to explain the failure of Hammer’s space western Moon Zero Two (1969), but the sheer looniness of the project can’t have helped. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll bid you a good night and look forward to doing the zombie stomp with you again next week when I have the opportunity to lay at your feet another dead bird from the dodgy chicken shop known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Neither Marooned nor Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun was a great box-office success, and the blame was put chiefly on the real moon landing that took place that very same year, an event that tended to make the cinema’s space age activities look rather out-of-date. The same excuse was used to explain the failure of Hammer’s space western Moon Zero Two (1969), but the sheer looniness of the project can’t have helped. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll bid you a good night and look forward to doing the zombie stomp with you again next week when I have the opportunity to lay at your feet another dead bird from the dodgy chicken shop known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun (1969)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews