SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“A campy futuristic tale where people hunt one another for sport. In this film, Victim and Hunter run around Italy trying to score a kill in front of the movie crews they arranged so they could make commercials from the footage.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

“What do they call The Hunger Games in France? Battle Royale with cheese!” When the film adaptation of Suzanne Collins‘ novel The Hunger Games (2012) was released it was heavily criticised for its similarities to the original novel and film adaptation of Battle Royale (2000) by Koushun Takami. For instance critic Susan Dominus wrote, “The parallels are striking enough that Collins’ work has been savaged on the blogosphere as a baldfaced rip-off (but) there are enough possible sources for the plot line that the two authors might well have hit on the same basic setup independently,” and Stephen King noted that the reality television ‘badlands’ in The Hunger Games were similar to his stories The Running Man and The Long Walk. The fact of the matter is, The Hunger Games has an entirely different set of cultural baggage and Collins simply drew on ideas that have been played out many times before, not to mention her intentional references to Greek mythology and ancient Roman ‘games’.

The ‘Government-Sanctioned Deathsport’ is a sub-genre that includes such films as The Tournament (2009), Death Race (2008), The Running Man (1987), Turkey Shoot (1982), Deathrace 2000 (1975), Rollerball (1975) and Terminal Island (1973). Back in the fifties, prize-winning author Robert Sheckley kick-started his career by having his stories published in many of the science fiction magazines of the era, and soon became known for his quick-witted stories which were often unpredictable, absurdist and broadly comical. One of Sheckley’s early works, the 1953 short story Seventh Victim, became the basis for the film The Tenth Victim (1965) also known by its original Italian title La Decima Vittima starring Marcello Mastrioni and Ursula Andress. Presumably three ‘victims’ were added to the title to avoid confusion with the Val Lewton witchcraft thriller The Seventh Victim (1943).

The ‘Government-Sanctioned Deathsport’ is a sub-genre that includes such films as The Tournament (2009), Death Race (2008), The Running Man (1987), Turkey Shoot (1982), Deathrace 2000 (1975), Rollerball (1975) and Terminal Island (1973). Back in the fifties, prize-winning author Robert Sheckley kick-started his career by having his stories published in many of the science fiction magazines of the era, and soon became known for his quick-witted stories which were often unpredictable, absurdist and broadly comical. One of Sheckley’s early works, the 1953 short story Seventh Victim, became the basis for the film The Tenth Victim (1965) also known by its original Italian title La Decima Vittima starring Marcello Mastrioni and Ursula Andress. Presumably three ‘victims’ were added to the title to avoid confusion with the Val Lewton witchcraft thriller The Seventh Victim (1943).

Always ready to make the most of a potentially profitable genre, Italian cinema has produced its fair share of science fiction films over the years, sometimes even predating some of America’s biggest successes, such as Mario Bava‘s Planet Of The Vampires (1965). However Elio Petri, who would go on to win an Oscar for the controversial ‘giallo’ film Investigation Of A Citizen Above Suspicion (1971), didn’t belong to the exploitation brand of genre directors. “Doing films devoid of any spectacular efficiency is almost pointless.” He always aimed at socially and politically challenging Italian society through the use of fiction, something he was frequently criticised for at the time.

Always ready to make the most of a potentially profitable genre, Italian cinema has produced its fair share of science fiction films over the years, sometimes even predating some of America’s biggest successes, such as Mario Bava‘s Planet Of The Vampires (1965). However Elio Petri, who would go on to win an Oscar for the controversial ‘giallo’ film Investigation Of A Citizen Above Suspicion (1971), didn’t belong to the exploitation brand of genre directors. “Doing films devoid of any spectacular efficiency is almost pointless.” He always aimed at socially and politically challenging Italian society through the use of fiction, something he was frequently criticised for at the time.

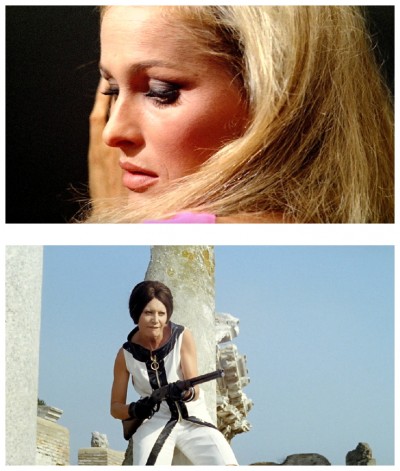

In the twenty-first century, murder has been partly legalised as a money-winning game so that violence and birthrates can be controlled. War has been abolished and the sole outlet for aggressions is the government-sponsored ‘Hunt’. The story of The Tenth Victim focuses on Marcello Polletti (Marcello Mastrioni) and Caroline Meredith (Ursula Andress) who are engaged in one these games as Victim and Hunter, respectively. In order to gain entry into the exclusive Tens Club, beautiful huntress Caroline must kill her tenth target in the Rome Colosseum for an international television audience. Her intended victim, Marcello, will be attempting to kill her and make his seventh successful defense. Preoccupied by monetary and domestic problems, Marcello seems uninterested in the Hunt. Caroline poses as a television journalist who wants to pay him for an interview in the Colosseum, where she plans to reveal who she is and kill him.

In the twenty-first century, murder has been partly legalised as a money-winning game so that violence and birthrates can be controlled. War has been abolished and the sole outlet for aggressions is the government-sponsored ‘Hunt’. The story of The Tenth Victim focuses on Marcello Polletti (Marcello Mastrioni) and Caroline Meredith (Ursula Andress) who are engaged in one these games as Victim and Hunter, respectively. In order to gain entry into the exclusive Tens Club, beautiful huntress Caroline must kill her tenth target in the Rome Colosseum for an international television audience. Her intended victim, Marcello, will be attempting to kill her and make his seventh successful defense. Preoccupied by monetary and domestic problems, Marcello seems uninterested in the Hunt. Caroline poses as a television journalist who wants to pay him for an interview in the Colosseum, where she plans to reveal who she is and kill him.

Naturally, they fall in love. But what can they do about his obligations to his family and to the vast television audience? This satirical film attempts to tackle the voyeurism of the media and shows death treated as a commodity in order to promote consumer goods. Despite its futuristic setting, the film refers to various topical subjects of the sixties, including the then-hot debate about divorce. Whereas Sheckley’s short story was written as a commentary on love, the need for excitement and the inevitability of self-deception, the film points out how difficult it can be to earn a living, how tiresome family problems can get, and how romance is always threatened by the long shadow of marriage, especially in Italy.

Naturally, they fall in love. But what can they do about his obligations to his family and to the vast television audience? This satirical film attempts to tackle the voyeurism of the media and shows death treated as a commodity in order to promote consumer goods. Despite its futuristic setting, the film refers to various topical subjects of the sixties, including the then-hot debate about divorce. Whereas Sheckley’s short story was written as a commentary on love, the need for excitement and the inevitability of self-deception, the film points out how difficult it can be to earn a living, how tiresome family problems can get, and how romance is always threatened by the long shadow of marriage, especially in Italy.

The Tenth Victim’s near-future world is constructed in relation to various Roman antique settings which link the fiction to the environment of contemporary Italian viewers, and modern art, in particular the pop-art movement: Roy Lichtenstein, Joe Tilson and George Segal are among the numerous artists quoted or imitated by the director, while the costumes of the ballet dancers are clearly inspired by Andre Courreges‘ space-age look. Petri also often resorts to monochromatic photography and reflections that divide the screen like images taken from a comic book. That generic bias leads to a comical and completely absurd series of different endings that play with conventions and, in an interesting way, seem to provide the spectators with every possible alternative.

The Tenth Victim’s near-future world is constructed in relation to various Roman antique settings which link the fiction to the environment of contemporary Italian viewers, and modern art, in particular the pop-art movement: Roy Lichtenstein, Joe Tilson and George Segal are among the numerous artists quoted or imitated by the director, while the costumes of the ballet dancers are clearly inspired by Andre Courreges‘ space-age look. Petri also often resorts to monochromatic photography and reflections that divide the screen like images taken from a comic book. That generic bias leads to a comical and completely absurd series of different endings that play with conventions and, in an interesting way, seem to provide the spectators with every possible alternative.

However, the cat-and-mouse game between the two main characters also emphasises important gender issues. With strangely peroxided hair, Marcello Mastrioni plays a male figure in crisis who doesn’t correspond at all to the Latin Lover type. The Tenth Victim deals with a recurring problem that plagues a lot of its counterparts in Italian cinema – society approves of the male being a seducer but, once he has settled down, he is constantly harassed by the women of his life, whether it be spouse or mistress. Mastrioni and Andress (who at one point wears a bra that fires ammunition) make a sexy screen couple, and the look of the film and a number of directorial touches by Petri are reminiscent of Frederico Fellini. Unfortunately, the novel science fiction premise gives way towards the end to a conventional and tired Italian sex-comedy story-line. The movie does have a cult following, but it would have a bigger following if it were only a bit more fun. Hold that thought while I take this opportunity to invite you to join me next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

However, the cat-and-mouse game between the two main characters also emphasises important gender issues. With strangely peroxided hair, Marcello Mastrioni plays a male figure in crisis who doesn’t correspond at all to the Latin Lover type. The Tenth Victim deals with a recurring problem that plagues a lot of its counterparts in Italian cinema – society approves of the male being a seducer but, once he has settled down, he is constantly harassed by the women of his life, whether it be spouse or mistress. Mastrioni and Andress (who at one point wears a bra that fires ammunition) make a sexy screen couple, and the look of the film and a number of directorial touches by Petri are reminiscent of Frederico Fellini. Unfortunately, the novel science fiction premise gives way towards the end to a conventional and tired Italian sex-comedy story-line. The movie does have a cult following, but it would have a bigger following if it were only a bit more fun. Hold that thought while I take this opportunity to invite you to join me next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews