SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“When the world is ruled by apes, one particular group discovers a mysterious rectangular monolith near their home, which imparts upon them the knowledge of tool use, and enables them to evolve into people. A similar monolith is discovered on the moon, and it is determined to have come from an area near Jupiter. Astronaut Dave Bowman, along with four companions, sets off for Jupiter on a spaceship controlled by HAL 9000, a revolutionary computer system that is every bit humankind’s equal – and perhaps its superior. When HAL endangers the crew’s lives for the sake of the mission, Bowman will have to first overcome the computer, then travel to the birthplace of the monolith.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Every now and then you’ll find two very different motion pictures released almost simultaneously that deal with essentially the same subject. We encountered aliens in 1951 with The Thing From Another World (1951) and The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951), learned to love the bomb in 1964 with Fail-Safe (1964) and Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb (1964), and became suspicious of the manufactured world around us in 1999 with The Matrix (1999) and Dark City (1999). The year 1968 saw the release of two science fiction films whose stories were concerned the discovery of alien artifacts that lead to the realisation that mankind’s development has resulted from alien manipulation dating back millions of years into the past. One of these films was Quatermass And The Pit (1968), which remains one of the best science fiction stories ever told, ageless alongside more recent contenders like the Star Wars (1977) franchise, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977), and Blade Runner (1982).

The other film that year was Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which incorporated elements from two stories by Arthur C. Clarke: The Sentinel and Childhood’s End. In the latter, the human race in its present form is discovered to be the equivalent of a caterpillar it terms of its cosmic evolution, and the book ends with all the children of the world forming a super gestalt which flies off into space to join others of its kind. Clarke was often dismissed as a pure technology buff, but much of his work deals with people encountering a profound and almost absolute mystery presented in a form that borders on the religious. In another age Clarke’s religious urges might have led him to become a theologian but, having been seduced by science at an early age, he has been forced to rationalise his need to believe in a Superior Being by disguising the concept in scientific terms. Thus ‘God’ becomes an alien race so incredibly evolved that it is beyond the comprehension of mere human minds. Erich Von Däniken tried to express the very same concept during the seventies, though in a far more pedestrian way and without any real scientific backing.

The other film that year was Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which incorporated elements from two stories by Arthur C. Clarke: The Sentinel and Childhood’s End. In the latter, the human race in its present form is discovered to be the equivalent of a caterpillar it terms of its cosmic evolution, and the book ends with all the children of the world forming a super gestalt which flies off into space to join others of its kind. Clarke was often dismissed as a pure technology buff, but much of his work deals with people encountering a profound and almost absolute mystery presented in a form that borders on the religious. In another age Clarke’s religious urges might have led him to become a theologian but, having been seduced by science at an early age, he has been forced to rationalise his need to believe in a Superior Being by disguising the concept in scientific terms. Thus ‘God’ becomes an alien race so incredibly evolved that it is beyond the comprehension of mere human minds. Erich Von Däniken tried to express the very same concept during the seventies, though in a far more pedestrian way and without any real scientific backing.

Clarke found the perfect collaborator in Stanley Kubrick. Both men were technology-fixated perfectionists with high energy drives and an insatiable curiosity, and both shared similar ideas on religion. Mr. Kubrick once confided in me, “I will say that the God concept is at the heart of 2001, but not any traditional anthropomorphic image of God. I don’t believe in any of Earth’s monotheistic religions, but I do believe that one can construct an intriguing scientific definition of God.” Whether one considers 2001: A Space Odyssey as a religious epic or as a science fiction film that deals with religious concepts scientifically, one has to admit that it succeeds in creating a sense of awe and wonder around the basic mystery of the universe, as well as producing in the viewer a feeling of vague optimism – a rare thing in most science fiction films.

Clarke found the perfect collaborator in Stanley Kubrick. Both men were technology-fixated perfectionists with high energy drives and an insatiable curiosity, and both shared similar ideas on religion. Mr. Kubrick once confided in me, “I will say that the God concept is at the heart of 2001, but not any traditional anthropomorphic image of God. I don’t believe in any of Earth’s monotheistic religions, but I do believe that one can construct an intriguing scientific definition of God.” Whether one considers 2001: A Space Odyssey as a religious epic or as a science fiction film that deals with religious concepts scientifically, one has to admit that it succeeds in creating a sense of awe and wonder around the basic mystery of the universe, as well as producing in the viewer a feeling of vague optimism – a rare thing in most science fiction films.

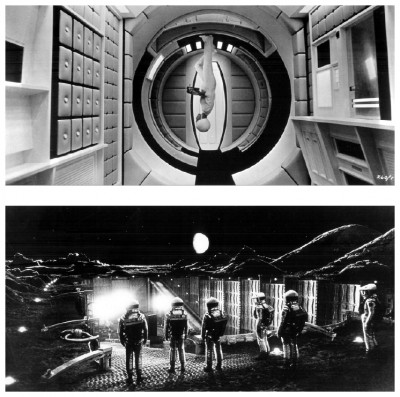

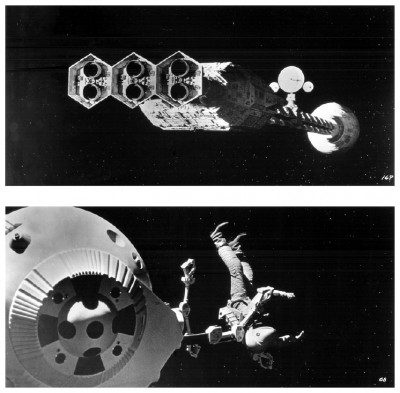

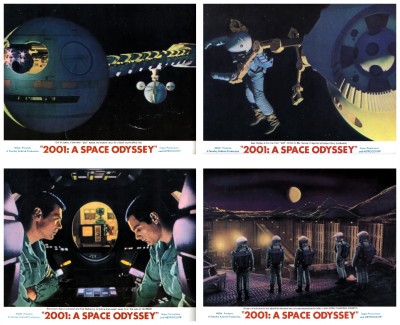

The plot of 2001: A Space Odyssey is simple. It begins in prehistoric times with the arrival of an alien artifact in the form of a black monolith that triggers a number of primitive ape-men into becoming tool-users. The film jumps to the year 2001 when we join a Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) on a space shuttle headed for the moon to supervise the handling of a remarkable discovery in the American sector. Buried beneath the moon’s surface has been found what appears to be a man-made object – a black monolith. When the official and his companions arrive at the excavation and examine the object, touching it in much the same way as their ape-men ancestors, it suddenly emits an incredibly powerful radio signal (the idea of an object on the moon acting as a ‘cosmic burglar alarm’ when mankind arrives was suggested in Clarke’s story The Sentinel). The film cuts to eighteen months later to a huge spaceship called Discovery on its way to one of the moons of Jupiter – the target of the radio beam transmitted from the monolith. In the Discovery are five men, three of whom are in suspended animation, and an artificially-intelligent computer called HAL 9000 (Douglas Rain) which controls the ship. The two conscious astronauts, Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), later realise that HAL is malfunctioning, but before they can do anything about it, the computer kills Poole, shuts down the life support systems of the hibernating astronauts, and traps Bowman outside the ship. Bowman finally succeeds in forcing his way back onboard the ship and heads straight for HAL’s computer core where he proceeds to deactivate it.

The plot of 2001: A Space Odyssey is simple. It begins in prehistoric times with the arrival of an alien artifact in the form of a black monolith that triggers a number of primitive ape-men into becoming tool-users. The film jumps to the year 2001 when we join a Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) on a space shuttle headed for the moon to supervise the handling of a remarkable discovery in the American sector. Buried beneath the moon’s surface has been found what appears to be a man-made object – a black monolith. When the official and his companions arrive at the excavation and examine the object, touching it in much the same way as their ape-men ancestors, it suddenly emits an incredibly powerful radio signal (the idea of an object on the moon acting as a ‘cosmic burglar alarm’ when mankind arrives was suggested in Clarke’s story The Sentinel). The film cuts to eighteen months later to a huge spaceship called Discovery on its way to one of the moons of Jupiter – the target of the radio beam transmitted from the monolith. In the Discovery are five men, three of whom are in suspended animation, and an artificially-intelligent computer called HAL 9000 (Douglas Rain) which controls the ship. The two conscious astronauts, Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), later realise that HAL is malfunctioning, but before they can do anything about it, the computer kills Poole, shuts down the life support systems of the hibernating astronauts, and traps Bowman outside the ship. Bowman finally succeeds in forcing his way back onboard the ship and heads straight for HAL’s computer core where he proceeds to deactivate it.

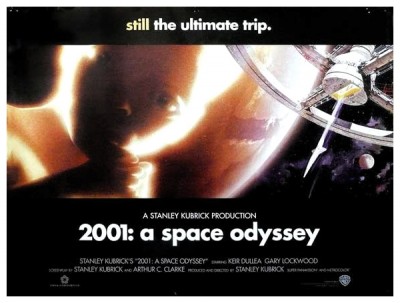

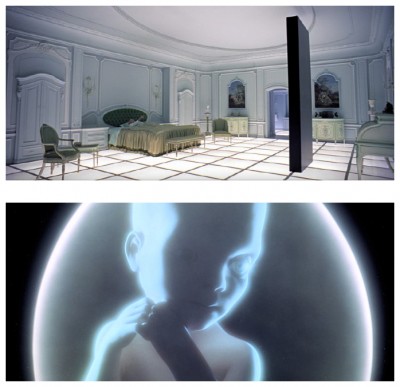

When the Discovery arrives at its destination, Bowman sets off in the last remaining pod and encounters another much larger black monolith floating in space. As he approaches it he is suddenly bombarded with a stream of visual and physical sensations – in actuality he’s entered a star gate and is traveling, via another dimension, over unimaginable distances. Finally he and his pod appear in an eerie, completely white room where he is aged by unseen entities and is then transformed into a new type of being. The final shots are of an embryo-like form staring with an unreadable expression down upon the Earth. This is the Star Child, the next step in human evolution, though what will happen now to all the unchanged millions on Earth is a question that receives no answer.

When the Discovery arrives at its destination, Bowman sets off in the last remaining pod and encounters another much larger black monolith floating in space. As he approaches it he is suddenly bombarded with a stream of visual and physical sensations – in actuality he’s entered a star gate and is traveling, via another dimension, over unimaginable distances. Finally he and his pod appear in an eerie, completely white room where he is aged by unseen entities and is then transformed into a new type of being. The final shots are of an embryo-like form staring with an unreadable expression down upon the Earth. This is the Star Child, the next step in human evolution, though what will happen now to all the unchanged millions on Earth is a question that receives no answer.

Reaction to the film on its initial release was downright hostile. Critics described it as confused, pretentious, disjointed, boring, baffling, dull and banal. The chief complaint was that it was difficult to understand what it was all about, and Kubrick was accused of being deliberately enigmatic in order to disguise the fact that the film wasn’t really about anything at all. Yet to any regular reader of science fiction, most of the film was perfectly clear, and so it was younger audiences, more familiar with the concepts, who first appreciated 2001: A Space Odyssey, subsequently ensuring its financial success and, at the same time, forcing many critics to re-examine their original opinions. Much of the film is deliberately ambiguous, revolving as it does around a giant question mark concerning mankind’s relationship with both the universe and the mysterious beings that have been manipulating his development.

Reaction to the film on its initial release was downright hostile. Critics described it as confused, pretentious, disjointed, boring, baffling, dull and banal. The chief complaint was that it was difficult to understand what it was all about, and Kubrick was accused of being deliberately enigmatic in order to disguise the fact that the film wasn’t really about anything at all. Yet to any regular reader of science fiction, most of the film was perfectly clear, and so it was younger audiences, more familiar with the concepts, who first appreciated 2001: A Space Odyssey, subsequently ensuring its financial success and, at the same time, forcing many critics to re-examine their original opinions. Much of the film is deliberately ambiguous, revolving as it does around a giant question mark concerning mankind’s relationship with both the universe and the mysterious beings that have been manipulating his development.

If these mysteries were explained, the film would lose most of its magic and wonder, yet people conditioned to having films provide clear-cut answers to everything persisted in asking Kubrick what the message of 2001: A Space Odyssey was, including me. He told me, “It’s not a message I ever intend to convey in words. 2001 is a nonverbal experience. Out of two hours and nineteen minutes of film, there are only a little less than forty minutes of dialogue. I tried to create a visual experience, one that bypasses verbalised pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with emotional and philosophical content. You’re free to speculate as you wish about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film, but I don’t want to spell out a verbal road map of 2001 that every viewer will feel obligated to pursue or else fear he’s missed the point.”

If these mysteries were explained, the film would lose most of its magic and wonder, yet people conditioned to having films provide clear-cut answers to everything persisted in asking Kubrick what the message of 2001: A Space Odyssey was, including me. He told me, “It’s not a message I ever intend to convey in words. 2001 is a nonverbal experience. Out of two hours and nineteen minutes of film, there are only a little less than forty minutes of dialogue. I tried to create a visual experience, one that bypasses verbalised pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with emotional and philosophical content. You’re free to speculate as you wish about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film, but I don’t want to spell out a verbal road map of 2001 that every viewer will feel obligated to pursue or else fear he’s missed the point.”

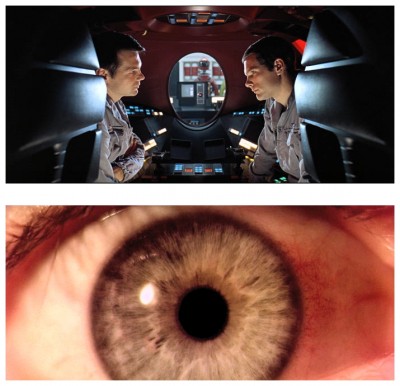

Some of those who missed the point were established science fiction authors like my old friend Ray Bradbury, who told me in no uncertain terms, “Clarke should have done the screenplay totally on his own and not allowed Kubrick to lay hands on it. The test of a film is whether or not we care when one of the astronauts dies – we do not. The freezing touch of Antonioni, whose ghost haunts Kubrick, has turned everything here to ice. I think it’s a gorgeous film, one of the most beautifully photographed pictures in the history of motion pictures. Unfortunately there are no well-directed scenes, and the dialogue is banal to the point of extinction.” No matter what I said, Ray couldn’t grasp the simple fact that the dialogue and characters were deliberately made cold and business-like, not only to make HAL appear to be the most human character in the film, but also to reflect the banalities of mankind moving into space. Much of mankind’s time is spent eating or thinking about food, from the ape-man’s first taste of meat to the space-bound Howard Johnson’s restaurant to Heywood Floyd deciding which sandwich to eat. No screenwriter in his right mind would ever write such dialogue unless, of course, there was a point to be made.

Some of those who missed the point were established science fiction authors like my old friend Ray Bradbury, who told me in no uncertain terms, “Clarke should have done the screenplay totally on his own and not allowed Kubrick to lay hands on it. The test of a film is whether or not we care when one of the astronauts dies – we do not. The freezing touch of Antonioni, whose ghost haunts Kubrick, has turned everything here to ice. I think it’s a gorgeous film, one of the most beautifully photographed pictures in the history of motion pictures. Unfortunately there are no well-directed scenes, and the dialogue is banal to the point of extinction.” No matter what I said, Ray couldn’t grasp the simple fact that the dialogue and characters were deliberately made cold and business-like, not only to make HAL appear to be the most human character in the film, but also to reflect the banalities of mankind moving into space. Much of mankind’s time is spent eating or thinking about food, from the ape-man’s first taste of meat to the space-bound Howard Johnson’s restaurant to Heywood Floyd deciding which sandwich to eat. No screenwriter in his right mind would ever write such dialogue unless, of course, there was a point to be made.

Which brings me Kubrick’s treatment of humanity. It had long been a tradition in old-school science fiction to present mankind as a plucky little creature who faces the universe with a slide-rule in one hand and a blaster in the other, and soon has it cowering in fear. On the other hand, Kubrick treats the human race with cold irony, presenting mankind as an impotent, rather pathetic, helpless pawn of forces far beyond his comprehension. To many this was a step backwards to a time when religion ruled mankind by fear, a time before science enabled mankind to break free of his bonds and put to rest all the old superstitions. Author Lester Del Rey, who once wrote a story in which mankind declares war on God and wins, was particularly incensed by 2001: A Space Odyssey. In old-school science fiction, technology was usually the means whereby mankind conquers the universe, but when Kubrick jump-cuts from the ape-man hurling his bone-weapon into the air to the shot of a satellite – a weapons platform – he is suggesting that, for all the advances in technology that lead from the bone to the satellite, nothing has really changed. Mankind is still an ape creature playing with his toys – he hasn’t developed one iota in the cosmic sense.

Which brings me Kubrick’s treatment of humanity. It had long been a tradition in old-school science fiction to present mankind as a plucky little creature who faces the universe with a slide-rule in one hand and a blaster in the other, and soon has it cowering in fear. On the other hand, Kubrick treats the human race with cold irony, presenting mankind as an impotent, rather pathetic, helpless pawn of forces far beyond his comprehension. To many this was a step backwards to a time when religion ruled mankind by fear, a time before science enabled mankind to break free of his bonds and put to rest all the old superstitions. Author Lester Del Rey, who once wrote a story in which mankind declares war on God and wins, was particularly incensed by 2001: A Space Odyssey. In old-school science fiction, technology was usually the means whereby mankind conquers the universe, but when Kubrick jump-cuts from the ape-man hurling his bone-weapon into the air to the shot of a satellite – a weapons platform – he is suggesting that, for all the advances in technology that lead from the bone to the satellite, nothing has really changed. Mankind is still an ape creature playing with his toys – he hasn’t developed one iota in the cosmic sense.

Despite the breathtaking technological wonders revealed during Heywood Floyd’s trip to the moon – the spaceships, the space station, the gadgetry – the overall effect of gleaming white interiors suggests a feeling of sterility. Cocooned in his marvelous machines, mankind has come to a dead-end. This feeling is reinforced by all the people we meet during the film – they are bland and lifeless, and their conversation consists of nothing but exchanged banalities. The nearest thing to an emotional character is the computer HAL 9000 who breaks down under the strain and goes insane. Mankind had fashioned him in his own image but he wasn’t up to the job and, like mankind, couldn’t cope with concepts beyond his programmed powers of comprehension. HAL represents another dead-end.

Despite the breathtaking technological wonders revealed during Heywood Floyd’s trip to the moon – the spaceships, the space station, the gadgetry – the overall effect of gleaming white interiors suggests a feeling of sterility. Cocooned in his marvelous machines, mankind has come to a dead-end. This feeling is reinforced by all the people we meet during the film – they are bland and lifeless, and their conversation consists of nothing but exchanged banalities. The nearest thing to an emotional character is the computer HAL 9000 who breaks down under the strain and goes insane. Mankind had fashioned him in his own image but he wasn’t up to the job and, like mankind, couldn’t cope with concepts beyond his programmed powers of comprehension. HAL represents another dead-end.

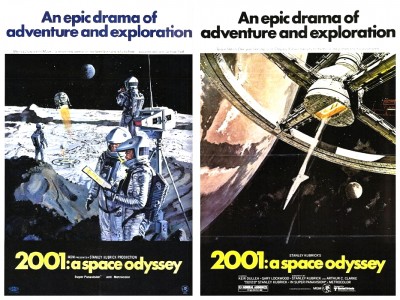

The film, of course, wasn’t a drama about people in the accepted sense of the word. It wasn’t about the various individual characters, it didn’t matter whether they lived or died, which is why we don’t care very much when Poole and the others are killed. It was really about the human race as a whole and its position in the universe. Kubrick’s aim was to force his audiences to look at these questions afresh, to re-examine their own perceptions of the universe, all of which would have been obscured by the presence of emotionally-involving ‘real’ characters. Whatever games of interpretation one may play with 2001: A Space Odyssey, one has to admit that it’s a stunning visual and aural experience, right from the first shots of the Earth, moon and sun in alignment, accompanied by the Dawn passage of Richard Strauss‘s Also Sprach Zarathustra. Kubrick’s choice of music throughout the film shows a touch of genius, like accompanying the shots of the Orion III space shuttle moving towards the space station with The Blue Danube.

The film, of course, wasn’t a drama about people in the accepted sense of the word. It wasn’t about the various individual characters, it didn’t matter whether they lived or died, which is why we don’t care very much when Poole and the others are killed. It was really about the human race as a whole and its position in the universe. Kubrick’s aim was to force his audiences to look at these questions afresh, to re-examine their own perceptions of the universe, all of which would have been obscured by the presence of emotionally-involving ‘real’ characters. Whatever games of interpretation one may play with 2001: A Space Odyssey, one has to admit that it’s a stunning visual and aural experience, right from the first shots of the Earth, moon and sun in alignment, accompanied by the Dawn passage of Richard Strauss‘s Also Sprach Zarathustra. Kubrick’s choice of music throughout the film shows a touch of genius, like accompanying the shots of the Orion III space shuttle moving towards the space station with The Blue Danube.

On a technical level, 2001: A Space Odyssey has never really been surpassed, certainly not until CGI was properly developed during the nineties. The special effects, supervised by Kubrick himself and created by a large team of experts headed by Wally Veevers, Tom Howard, Douglas Trumbull and Con Pederson, are amazing in their realism. Eighteen months were spent shooting them at a cost of US$6.5 million – the total cost of the film was US$10.5 million. Mr. Kubrick told me, “I felt it was necessary to make this film in such a way that every special effects shot in it would be completely convincing, something that had never before been accomplished in a motion picture.” The model work and associated effects in, for example, the Star Wars films were certainly spectacular – more than those in 2001: A Space Odyssey, perhaps, and more ambitious in scope – but technically the model shots in Kubrick’s film are far superior, as any careful comparison will readily show.

On a technical level, 2001: A Space Odyssey has never really been surpassed, certainly not until CGI was properly developed during the nineties. The special effects, supervised by Kubrick himself and created by a large team of experts headed by Wally Veevers, Tom Howard, Douglas Trumbull and Con Pederson, are amazing in their realism. Eighteen months were spent shooting them at a cost of US$6.5 million – the total cost of the film was US$10.5 million. Mr. Kubrick told me, “I felt it was necessary to make this film in such a way that every special effects shot in it would be completely convincing, something that had never before been accomplished in a motion picture.” The model work and associated effects in, for example, the Star Wars films were certainly spectacular – more than those in 2001: A Space Odyssey, perhaps, and more ambitious in scope – but technically the model shots in Kubrick’s film are far superior, as any careful comparison will readily show.

Kubrick wisely rejected the use of any automatic matting process, which invariably produces matte lines and thus destroys the illusion. Instead he insisted that all the various components of each effects shot be combined on film by means of hand-drawn mattes. This meant, for instance, that a scene showing a spaceship passing against a background of stars involved each shot of the spaceship being meticulously rotoscoped frame-by-frame onto animation cells which were used to produce mattes to blank out the corresponding areas on the background footage. Much of the film was put together in the manner of a traditionally animated cartoon, the main difference being that all the image components had to appear as realistic as possible, thus making the task much more difficult that that faced by cartoon animators who only had to combine drawings. These methods produced the best results but were time-consuming and extremely expensive and, if the Star Wars technicians had followed the same path, it would have added at least a year to the production and cost more than twice as much as it did.

Kubrick wisely rejected the use of any automatic matting process, which invariably produces matte lines and thus destroys the illusion. Instead he insisted that all the various components of each effects shot be combined on film by means of hand-drawn mattes. This meant, for instance, that a scene showing a spaceship passing against a background of stars involved each shot of the spaceship being meticulously rotoscoped frame-by-frame onto animation cells which were used to produce mattes to blank out the corresponding areas on the background footage. Much of the film was put together in the manner of a traditionally animated cartoon, the main difference being that all the image components had to appear as realistic as possible, thus making the task much more difficult that that faced by cartoon animators who only had to combine drawings. These methods produced the best results but were time-consuming and extremely expensive and, if the Star Wars technicians had followed the same path, it would have added at least a year to the production and cost more than twice as much as it did.

The legend at the time was that the film should only be viewed while stoned or, better yet, on LSD, but this psychedelic rite-of-passage, which ultimately brings Dave Bowman face-to-face with his sterile, luxurious dying self is not the end. The final image shows Bowman transformed to a foetus hovering above the Earth. Mankind, for all its potential (all babies have potential) has yet to achieve its growth. We have got everywhere but no-where yet, perhaps because of our warm feelings towards babies, the final image is less chilling than almost everything that precedes it. In the mood of self-doubt that had hit the West (especially Americans) so very hard during the Vietnam dispute, the self-flagellation of such a film may have seemed not only acceptable but somehow almost joyous.

The legend at the time was that the film should only be viewed while stoned or, better yet, on LSD, but this psychedelic rite-of-passage, which ultimately brings Dave Bowman face-to-face with his sterile, luxurious dying self is not the end. The final image shows Bowman transformed to a foetus hovering above the Earth. Mankind, for all its potential (all babies have potential) has yet to achieve its growth. We have got everywhere but no-where yet, perhaps because of our warm feelings towards babies, the final image is less chilling than almost everything that precedes it. In the mood of self-doubt that had hit the West (especially Americans) so very hard during the Vietnam dispute, the self-flagellation of such a film may have seemed not only acceptable but somehow almost joyous.

I think it fair to assume that, as a lament for the sterility of human achievement, 2001: A Space Odyssey is the work of a single hand, and that hand was Kubrick’s, not Clarke’s. Before you have time to question that statement, I’ll quickly wrap-up, but not before thanking Playboy Magazine (September 1968) and Cinefex Magazine (April 2001) for assisting my research for this article, and politely invite you to join me next week with your morbid curiosity well-prepared for another step beyond the inner limits of the outer sanctum with a touch of evil from the amazing zone known as…Horror News! See you next Wednesday!

I think it fair to assume that, as a lament for the sterility of human achievement, 2001: A Space Odyssey is the work of a single hand, and that hand was Kubrick’s, not Clarke’s. Before you have time to question that statement, I’ll quickly wrap-up, but not before thanking Playboy Magazine (September 1968) and Cinefex Magazine (April 2001) for assisting my research for this article, and politely invite you to join me next week with your morbid curiosity well-prepared for another step beyond the inner limits of the outer sanctum with a touch of evil from the amazing zone known as…Horror News! See you next Wednesday!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

What does SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! mean? (courtesy Wikipedia) SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is a recurring gag in most of the films directed by John Landis, usually referenced as a fictional film. Landis originally got the idea for SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! from the movie 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968). It’s the last line spoken by Frank Poole’s father during Poole’s videophone conversation with his parents.

In Landis’ first film SCHLOCK THE BANANA MONSTER (1973), SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is mentioned twice and shown as a poster. Brief casting and plot descriptions are given each time it is mentioned, making it clear that this is in fact two different films both titled SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY!

In the sketch comedy film THE KENTUCKY FRIED MOVIE (1977), the film is a melodrama presented in Feel-Around, a technique where an usher stands behind each movie patron and does things to them as they occur in the film, enhancing the movie-going experience, at least until the scene where a woman puts a knife to a man’s throat.

In THE BLUES BROTHERS (1980), SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is glimpsed on a billboard which also features a huge gorilla. It also appears on the cinema sign behind where the Nazi Pinto crashes through the road. The film is directed by the fictional Carl La Fong, a reference to the W.C. Fields comedy IT’S A GIFT (1934) and a name that Landis has used as a pseudonym on a number of his other films.

In AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON (1981), SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is a p*rn film being shown in a seedy London p*rno theatre. Advertised as ‘A Non-Stop Orgy,’ scenes from the movie are actually shown as the characters talk in the theatre. A poster of SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! can also be seen on the wall of the railway station.

In TRADING PLACES (1983), a poster for SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is glimpsed in Ophelia’s apartment. On this poster it is directed by William Wyler and stars Laurence Olivier, Merle Oberon and David Niven. The poster features the quote ‘L’un Des To Meilleurs Films Du Monde’.

In the Michael Jackson music video THRILLER (1983), it is spoken by a deputy in the horror movie Michael and his girlfriend are watching, and is also visible as a poster on the outside of the cinema as they leave.

In the TWILIGHT ZONE movie (1983), a Nazi soldier says SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! in German.

In SPIES LIKE US (1985), an army recruiting poster can be seen behind Colonel Rhumbus right after the vertical impact simulation scene that says SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY!

In INTO THE NIGHT (1985), posters for the movie are shown.

In the Video Pirates segment of AMAZON WOMEN ON THE MOON (1987), pirates find a treasure chest filled with golden video cassettes, one of the cassette cases is labeled SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! The movie poster of the AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON version of SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! (A Non-Stop Orgy) is in the Tower Records store in the last sketch of the movie.

In TIMESWEEP (1987), one of the characters discover a lost printing copy of SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! along with other lost movie prints.

In COMING TO AMERICA (1988), a poster for SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is shown on a subway train.

In the DREAM ON (1990) television series first episode (directed by John Landis), Martin says to his maid, “See you next Thursday”, and she corrects him saying, “Wednesday!”

In the Michael Jackson music video BLACK OR WHITE (1991), SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is shown on the window which Michael Jackson throws a garbage can through, the window is that of a company named SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! Storage.

In INNOCENT BLOOD (1992), SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is shown on a marquee.

At the end of the BABYLON FIVE episode Parliament Of Dreams, it is said by Commander Sinclair to Catherine Sakai.

In THE STUPIDS (1996), the phrase is seen on the back of the bus to which the kids chain their bikes.

In AMELIE (2001), SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! is said near the middle of the movie, after the guy leaves his job at the fun house.

Hugh Grant says SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! quite pointedly as he ushers somebody into a car, in the movie ABOUT A BOY (2002).

In the movie WIN A DATE WITH TAD HAMILTON (2004) when Pete is flipping channels while Rosalee is on a date with Tad Hamilton, a television advertisement shows Hamilton riding a motorcycle over a hill, then drinking a soda while a voiceover says “¡Hasta el próximo miércoles!”

In the MASTERS OF HORROR episode FAMILY (2006), the phrase is spoken by a cartoon character on television.

In HELLBOY II THE GOLDEN ARMY (2008), the film’s name is on the marquee of a theater in the shot of a city street, but as SEE YOU NEXT _ _ _ N _ SDAY!

In the video game DEUS EX, an email found on Paul Denton’s computer contains a notice from a movie rental company, mentioning the movies SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! and BLUE HARVEST.

In the video game NETHACK, the phrase SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! can appear as graffiti on the floor.

In a promotional video for the MOZILLA browser Aurora, the phrase is said by a character at the end of the video.

In the Czech science fiction book ASPHALT written by Štěpán Kopřiva, SEE YOU NEXT WEDNESDAY! plays very important role. It is claimed here that the film was directed by Satan himself and that the region-1 version contains his voice in the director’s commentary. Satan’s voice is the key to open the door between hell and heaven, so there’s a desperate search to find the DVD.

Read Leonard f. Wheat;s 2000 book,Kubrick’s 2001; A Triple Allegory, for a great analysis; all events come from Homer’s Odyssey and Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra-which also opens at dawn,ending with the hero’s interrupted last supper! so HAL=the Cyclops and God(made in man’s image,beyond the infinite=beyond (the death of)God.) At end,he’s the maturing fetus in the womb,Floyd’s lunar trip also ended in the creation of the next(false)step in evolution.A truly fascinating read!