SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

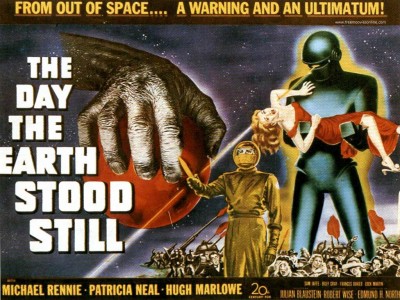

“An alien named Klaatu, with his mighty robot Gort, land their spacecraft on Cold War-era Earth just after the end of World War Two. They bring an important message to the planet that Klaatu wishes to tell to representatives of all nations. However, communication turns out to be difficult so, after learning something about the natives, Klaatu decides on an alternative approach.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

The world was warned by a superior force to mend its evil ways or face total destruction in The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951). This time the warning came from a community of interplanetary busybodies. The film is regarded by many as one of the few real science fiction film classics. Admittedly, it’s more sophisticated in style than most fifties science fiction, with slick direction by Robert Wise, polished screenplay by Edmund North, an above-average cast of Michael Rennie, Patricia Neal, Hugh Marlowe and Sam Jaffe, but the basic story and theme are badly flawed.

The film begins with a flying saucer landing in Washington DC, and from it emerges a humanoid alien, promptly shot by one of the nervous troops who have swiftly surrounded the spacecraft. At this point a ten-foot-tall robot appears and disintegrate a number of guns and a tank before being verbally deactivated by the wounded alien (Michael Rennie). The alien, named Klaatu, is then taken to a military hospital but escapes and, incognito, hides out in a boarding house where he develops a friendship with a young widow (Patricia Neal) and her son (Billy Gray). We learn that his mission on Earth is to deliver a warning to all the world leaders, but first he has to arrange a demonstration of the power at his command. He does this by shutting down all electrically powered machinery across the world for one hour – the sequence that provides the film’s title.

The film begins with a flying saucer landing in Washington DC, and from it emerges a humanoid alien, promptly shot by one of the nervous troops who have swiftly surrounded the spacecraft. At this point a ten-foot-tall robot appears and disintegrate a number of guns and a tank before being verbally deactivated by the wounded alien (Michael Rennie). The alien, named Klaatu, is then taken to a military hospital but escapes and, incognito, hides out in a boarding house where he develops a friendship with a young widow (Patricia Neal) and her son (Billy Gray). We learn that his mission on Earth is to deliver a warning to all the world leaders, but first he has to arrange a demonstration of the power at his command. He does this by shutting down all electrically powered machinery across the world for one hour – the sequence that provides the film’s title.

When the soldiers and scientists arrive on the scene, Klaatu delivers his message which concludes with the words: “Soon one of your nations will apply atomic power to rockets. Up till now we have not cared how you solved your petty squabbles. But if you threaten to extend your violence, this Earth of yours will be reduced to a burnt-out cinder. Your choice is simple – join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration.” My old friend and fellow film critic Jeff Rovin once told me he thought this speech was the finest soliloquy in science fiction film history, but as the alien’s civilisation is supposed to be peace-loving it hardly seems logical or morally acceptable that it should threaten the natives on Earth with an even greater act of violence. Nor is their solution very attractive, namely that we should submit ourselves to the rule of a group of implacable authoritarian robots like the one which accompanied the alien to Earth. For the robot, we discover, is not the alien’s servant but his supervisor, one of many built to keep law and order in the universe. The idea of placing our basic human rights in the custody of a machine (or any so-called superior force) is not only an admission of defeat, but also one that smacks of totalitarianism. Nineteen years later we were shown what happens when a machine is allowed to take over in Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970).

When the soldiers and scientists arrive on the scene, Klaatu delivers his message which concludes with the words: “Soon one of your nations will apply atomic power to rockets. Up till now we have not cared how you solved your petty squabbles. But if you threaten to extend your violence, this Earth of yours will be reduced to a burnt-out cinder. Your choice is simple – join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration.” My old friend and fellow film critic Jeff Rovin once told me he thought this speech was the finest soliloquy in science fiction film history, but as the alien’s civilisation is supposed to be peace-loving it hardly seems logical or morally acceptable that it should threaten the natives on Earth with an even greater act of violence. Nor is their solution very attractive, namely that we should submit ourselves to the rule of a group of implacable authoritarian robots like the one which accompanied the alien to Earth. For the robot, we discover, is not the alien’s servant but his supervisor, one of many built to keep law and order in the universe. The idea of placing our basic human rights in the custody of a machine (or any so-called superior force) is not only an admission of defeat, but also one that smacks of totalitarianism. Nineteen years later we were shown what happens when a machine is allowed to take over in Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970).

The twist of the robot turning out to be in charge was the main point of the original story Farewell To The Master by Harry Bates, published in Astounding Magazine in 1940, but it wasn’t the plot that attracted 20th Century Fox producer Julian Blaustein to the idea so much as the scene where the flying saucer lands and the alien emerges to receive a dose of human hospitality. Blaustein told me: “The thing that grabbed my attention was the response of people to the unknown. Klaatu holds his hand up with something that looks unfamiliar to them and he is immediately shot. It was a terribly significant moment for me in terms of story.” Blaustein had started reading science fiction in 1949 when he became aware of the booming circulation figures of science fiction magazines. On the basis of these, he decided that he would be able to persuade studio CEO Darryl Zanuck about the feasibility of making a science fiction movie. One of the reasons he chose Farewell To The Master was that it was set on Earth and would be relatively cheap to make.

The twist of the robot turning out to be in charge was the main point of the original story Farewell To The Master by Harry Bates, published in Astounding Magazine in 1940, but it wasn’t the plot that attracted 20th Century Fox producer Julian Blaustein to the idea so much as the scene where the flying saucer lands and the alien emerges to receive a dose of human hospitality. Blaustein told me: “The thing that grabbed my attention was the response of people to the unknown. Klaatu holds his hand up with something that looks unfamiliar to them and he is immediately shot. It was a terribly significant moment for me in terms of story.” Blaustein had started reading science fiction in 1949 when he became aware of the booming circulation figures of science fiction magazines. On the basis of these, he decided that he would be able to persuade studio CEO Darryl Zanuck about the feasibility of making a science fiction movie. One of the reasons he chose Farewell To The Master was that it was set on Earth and would be relatively cheap to make.

Very few science fiction films made in the fifties were based on the work of real authors, and when they were, precious little remained of the original in the finished product. This is certainly true of The Day The Earth Stood Still, although the original story is a rather hoary piece of work when read today, and Edmund North‘s screenplay was a great improvement on it. Harry Bates, who was editor of Astounding Stories from 1930 to 1933, can best be described as a ‘pre-Campbell’ science fiction writer, and his work displays all that was wrong with magazine science fiction in the thirties, before John W. Campbell Junior imposed his personality on the genre. Still, Bates deserved more than the US$500 which was all he received for the sale of the film rights. The rights were actually sold to the filmmakers by the copyright-holders Street & Smith Publications for US$1000 without their bothering to inform Bates of the sale, who was quite bitter about it to the very end. He told me, “I thought the movie was very good, but it had nothing to do with my story!”

Very few science fiction films made in the fifties were based on the work of real authors, and when they were, precious little remained of the original in the finished product. This is certainly true of The Day The Earth Stood Still, although the original story is a rather hoary piece of work when read today, and Edmund North‘s screenplay was a great improvement on it. Harry Bates, who was editor of Astounding Stories from 1930 to 1933, can best be described as a ‘pre-Campbell’ science fiction writer, and his work displays all that was wrong with magazine science fiction in the thirties, before John W. Campbell Junior imposed his personality on the genre. Still, Bates deserved more than the US$500 which was all he received for the sale of the film rights. The rights were actually sold to the filmmakers by the copyright-holders Street & Smith Publications for US$1000 without their bothering to inform Bates of the sale, who was quite bitter about it to the very end. He told me, “I thought the movie was very good, but it had nothing to do with my story!”

Technically the film stands up very well today and the scenes involving the landing of the flying saucer and the subsequent events around it possess an eerie quality assisted by Bernard Herrmann‘s marvelously alien-sounding electronic soundtrack. The flying saucer itself, designed by Lyle Wheeler and Addison Hehr, looks on the outside exactly as one would expect a real one to look like, although its interior was a bit of a disappointment, and revealing it destroyed the essential mystery of the spacecraft. The giant robot Gort, despite looking a little rubbery behind the knees, was also very impressive. Inside the suit, which consisted of rubber sprayed with metallic silver paint and a head made of sheet metal, was Mr. Lock Martin, doorman at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, chosen for the role because he was the tallest man in Hollywood.

Technically the film stands up very well today and the scenes involving the landing of the flying saucer and the subsequent events around it possess an eerie quality assisted by Bernard Herrmann‘s marvelously alien-sounding electronic soundtrack. The flying saucer itself, designed by Lyle Wheeler and Addison Hehr, looks on the outside exactly as one would expect a real one to look like, although its interior was a bit of a disappointment, and revealing it destroyed the essential mystery of the spacecraft. The giant robot Gort, despite looking a little rubbery behind the knees, was also very impressive. Inside the suit, which consisted of rubber sprayed with metallic silver paint and a head made of sheet metal, was Mr. Lock Martin, doorman at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, chosen for the role because he was the tallest man in Hollywood.

I’d also like to make special mention of Sam Jaffe who, in the very same year, was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance in The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and became a Hollywood mainstay, working with such diverse directors as Frank Capra in Lost Horizon (1937) and James Cameron in Battle Beyond The Stars (1980). He may be best remembered for playing the title role in Gunga Din (1939) and Simonides in Ben-Hur (1959). Jaffe was blacklisted by the studio chiefs during the fifties, supposedly for being a Communist sympathiser. Jaffe co-starred in the television series Ben Casey as Doctor David Zorba from 1961 to 1965 alongside Vince Edwards and had many guest starring roles on other series, including Batman as Zoltan Zorba, and the western Alias Smith And Jones starring Peter Duel and Ben Murphy, and in 1975 he co-starred as a retired doctor, who is murdered by Janet Leigh in the Columbo episode Forgotten Lady.

I’d also like to make special mention of Sam Jaffe who, in the very same year, was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance in The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and became a Hollywood mainstay, working with such diverse directors as Frank Capra in Lost Horizon (1937) and James Cameron in Battle Beyond The Stars (1980). He may be best remembered for playing the title role in Gunga Din (1939) and Simonides in Ben-Hur (1959). Jaffe was blacklisted by the studio chiefs during the fifties, supposedly for being a Communist sympathiser. Jaffe co-starred in the television series Ben Casey as Doctor David Zorba from 1961 to 1965 alongside Vince Edwards and had many guest starring roles on other series, including Batman as Zoltan Zorba, and the western Alias Smith And Jones starring Peter Duel and Ben Murphy, and in 1975 he co-starred as a retired doctor, who is murdered by Janet Leigh in the Columbo episode Forgotten Lady.

Before signing off this week I must profusely thank Cinefantastique Magazine volume four issue #4 (1976) for their invaluable assistance with my research, and now I’ll politely request your company next week when I have another opportunity to inflict upon you the tortures of the damned from that dark, bottomless pit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Before signing off this week I must profusely thank Cinefantastique Magazine volume four issue #4 (1976) for their invaluable assistance with my research, and now I’ll politely request your company next week when I have another opportunity to inflict upon you the tortures of the damned from that dark, bottomless pit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews