SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

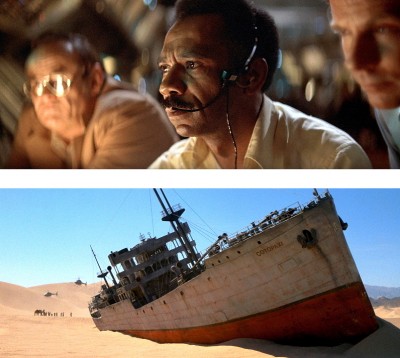

“Cableman Roy Neary is one of several people who experience a close encounter of the first kind, witnessing UFOs flying through the night sky. He is subsequently haunted by a mountain-like image in his head and becomes obsessed with discovering what it represents, putting severe strain on his marriage. Meanwhile, government agents around the world have a close encounter of the second kind, discovering physical evidence of otherworldly visitors in the form of military vehicles that went missing decades ago suddenly appearing in the middle of nowhere. Roy and the agents both follow the clues they have been given to reach a site where they will have a close encounter of the third kind: contact.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Younger readers may not appreciate the fact that, before 1977, science fiction films remained on the fringes of the mainstream. Even well-known films like Metropolis (1926), Forbidden Planet (1956) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) were considered novelties when compared to their cinema contemporaries. This changed in 1977 with the release of two of the highest-earning films in history, both of which were science fiction yet at opposite ends of the genre spectrum. The first was Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977). The second big blockbuster of the year was Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977) and, although totally different to Star Wars, it has one basic feature in common: It has more to do with mysticism and spirituality than with science fiction.

Written and directed by Steven Spielberg, Close Encounters properly begins in a small rural town in Indiana where a number of people experience a strange manifestation. It starts in the house of Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon) when all her young son’s toys come to life. The boy, three-year-old Barry (Cary Guffey), is delighted but his mother’s reaction is one of sheer panic, particularly when every electrical gadget in the house begins to run wild. The next person to become involved is power company worker Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), who sets out in his truck to investigate the sudden power failure only to be caught up in a nightmarish series of phenomena he finds incomprehensible. Strange lights surround him, the dashboard of his truck goes wild and his equipment starts to move around as if with a life of its own. Then he sees, hovering overhead, the glowing shape of a flying saucer. The evening’s events have a profound effect on him and, from then on, he begins to act like a man who has undergone a deeply religious experience. He becomes obsessed with UFOs, loses his job as a result and alienates his wife (Teri Garr) and his three children when he persists in trying to sculpt the shape of a strange mountain (a vision firmly implanted in his mind since his encounter with the UFO) with whatever material is at hand, be it soap, garden soil or mashed potatoes.

Written and directed by Steven Spielberg, Close Encounters properly begins in a small rural town in Indiana where a number of people experience a strange manifestation. It starts in the house of Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon) when all her young son’s toys come to life. The boy, three-year-old Barry (Cary Guffey), is delighted but his mother’s reaction is one of sheer panic, particularly when every electrical gadget in the house begins to run wild. The next person to become involved is power company worker Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), who sets out in his truck to investigate the sudden power failure only to be caught up in a nightmarish series of phenomena he finds incomprehensible. Strange lights surround him, the dashboard of his truck goes wild and his equipment starts to move around as if with a life of its own. Then he sees, hovering overhead, the glowing shape of a flying saucer. The evening’s events have a profound effect on him and, from then on, he begins to act like a man who has undergone a deeply religious experience. He becomes obsessed with UFOs, loses his job as a result and alienates his wife (Teri Garr) and his three children when he persists in trying to sculpt the shape of a strange mountain (a vision firmly implanted in his mind since his encounter with the UFO) with whatever material is at hand, be it soap, garden soil or mashed potatoes.

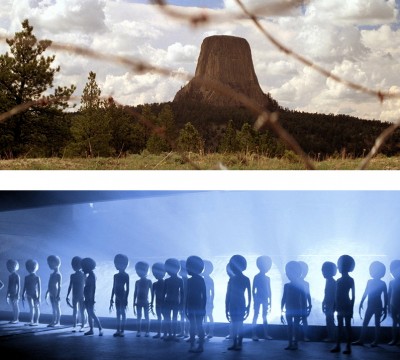

This vision is shared by other residents of Indiana who have also seen the lights of the UFO, and Jillian is convinced that her son has been kidnapped by the flying saucers. From then on the film concerns their attempts to discover what the mountain-like shape represents, and this is inter-cut with a subplot concerning a mysterious group of scientific and military experts, headed by Frenchman Claude Lacombe (François Truffaut) and his translator (Bob Balaban), who are traveling the world trying to decipher and interpret the musical signals and lights that have been recorded emanating from various UFOs. This middle part is perhaps the weakest part of the film, as Speilberg was obliged to pad it out with a number of extraneous sequences and subplots. The film’s final forty minutes are the important ones. Roy, Jillian and the others converge with Lacombe’s team at a mountain called Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, which turns out to be the mysterious mountain in the vision. They all wait for the titular ‘encounter’, Lacombe and his men have brought along a Moog synthesiser and what looks like an up-ended disco dance floor with which they hope to communicate with the aliens. They are not disappointed. The UFOs, in the form of a dazzling display of lights, appear on cue and there follows a barrage of spectacular visuals accompanied by bursts of electronica, which culminates in the landing of the vast alien mothership, a circular object with cathedral-like spires rising from its centre and covered with hundred of illuminated windows. Then the aliens appear – first a swarm of child-like aliens, glowing and indistinct like humanoid fireflies, followed by the chief alien whom we see in close-up – an ethereal and apparently androgynous figure with a long neck and no hair. As he stands there, Lacombe steps forward and smiles and, after a pause, the alien smiles back.

This vision is shared by other residents of Indiana who have also seen the lights of the UFO, and Jillian is convinced that her son has been kidnapped by the flying saucers. From then on the film concerns their attempts to discover what the mountain-like shape represents, and this is inter-cut with a subplot concerning a mysterious group of scientific and military experts, headed by Frenchman Claude Lacombe (François Truffaut) and his translator (Bob Balaban), who are traveling the world trying to decipher and interpret the musical signals and lights that have been recorded emanating from various UFOs. This middle part is perhaps the weakest part of the film, as Speilberg was obliged to pad it out with a number of extraneous sequences and subplots. The film’s final forty minutes are the important ones. Roy, Jillian and the others converge with Lacombe’s team at a mountain called Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, which turns out to be the mysterious mountain in the vision. They all wait for the titular ‘encounter’, Lacombe and his men have brought along a Moog synthesiser and what looks like an up-ended disco dance floor with which they hope to communicate with the aliens. They are not disappointed. The UFOs, in the form of a dazzling display of lights, appear on cue and there follows a barrage of spectacular visuals accompanied by bursts of electronica, which culminates in the landing of the vast alien mothership, a circular object with cathedral-like spires rising from its centre and covered with hundred of illuminated windows. Then the aliens appear – first a swarm of child-like aliens, glowing and indistinct like humanoid fireflies, followed by the chief alien whom we see in close-up – an ethereal and apparently androgynous figure with a long neck and no hair. As he stands there, Lacombe steps forward and smiles and, after a pause, the alien smiles back.

Like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters is a religious film. The aliens in both represent God or gods, but whereas Kubrick’s masterpiece they remained beyond human comprehension – cold impersonal entities playing some sort of cosmic game with mankind for incomprehensible reasons of their own – in Close Encounters they reveal themselves as benign friendly beings who have humanity’s best interests at heart. As critic Pauline Kael observed, the message of the film is, “God is up there in a crystal-chandelier spaceship, and he likes us.” The main flaw in the film is that it appears to be the result of two entirely different scripts. The mischevious and downright sadistic behaviour of the UFOs in the early stages of the film bears no relation to the obviously friendly creatures who are revealed at the end.

Like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters is a religious film. The aliens in both represent God or gods, but whereas Kubrick’s masterpiece they remained beyond human comprehension – cold impersonal entities playing some sort of cosmic game with mankind for incomprehensible reasons of their own – in Close Encounters they reveal themselves as benign friendly beings who have humanity’s best interests at heart. As critic Pauline Kael observed, the message of the film is, “God is up there in a crystal-chandelier spaceship, and he likes us.” The main flaw in the film is that it appears to be the result of two entirely different scripts. The mischevious and downright sadistic behaviour of the UFOs in the early stages of the film bears no relation to the obviously friendly creatures who are revealed at the end.

The release of Close Encounters coincided with revived interest in UFOs. Reports of sightings were on the increase and even then-President Carter claimed to have seen a flying saucer. NASA had received an official request to investigate possible new methods of approaching the whole question. The growing cult of UFO-ology is considered by some to be like a new religion, a reflection of the need of people who can’t accept the traditional religions but want to believe that something ‘Out There’ is interested in them. Anthropologist Ronald Grunloh proposed the theory that, like man’s oldest religious beliefs, UFOs and alien abductions are a modern manifestation of various subjective experiences that have hitherto been interpreted as religious visions. Neatly reversing the then-popular theories of Erik Von Daniken, Grunloh stated that people who think they see ‘flying saucers’ are really seeing the same thing as the biblical prophets saw, but whereas the latter tended to visualise lions, chariots and hoofed creatures on fiery clouds, people today visualise short bald men in glowing spacesuits. “All human beings can have spontaneous visions,” said Grunloh, “even in groups. If we understood hallucinations better, we might know why the shapes and colours and lights are so often the same.” He believes that these religious visions/UFO sightings increase in number during periods of social upheaval, but that their cause is within ourselves and not in the sky. This view was completely supported by scientist and author Isaac Asimov who, at the time, publicly denounced Close Encounters as a dangerous influence on impressionable minds and contributing to the general move away from rationalism towards mysticism. “Such people can be stampeded into all kinds of fantasy, folly and warfare,” he warned.

The release of Close Encounters coincided with revived interest in UFOs. Reports of sightings were on the increase and even then-President Carter claimed to have seen a flying saucer. NASA had received an official request to investigate possible new methods of approaching the whole question. The growing cult of UFO-ology is considered by some to be like a new religion, a reflection of the need of people who can’t accept the traditional religions but want to believe that something ‘Out There’ is interested in them. Anthropologist Ronald Grunloh proposed the theory that, like man’s oldest religious beliefs, UFOs and alien abductions are a modern manifestation of various subjective experiences that have hitherto been interpreted as religious visions. Neatly reversing the then-popular theories of Erik Von Daniken, Grunloh stated that people who think they see ‘flying saucers’ are really seeing the same thing as the biblical prophets saw, but whereas the latter tended to visualise lions, chariots and hoofed creatures on fiery clouds, people today visualise short bald men in glowing spacesuits. “All human beings can have spontaneous visions,” said Grunloh, “even in groups. If we understood hallucinations better, we might know why the shapes and colours and lights are so often the same.” He believes that these religious visions/UFO sightings increase in number during periods of social upheaval, but that their cause is within ourselves and not in the sky. This view was completely supported by scientist and author Isaac Asimov who, at the time, publicly denounced Close Encounters as a dangerous influence on impressionable minds and contributing to the general move away from rationalism towards mysticism. “Such people can be stampeded into all kinds of fantasy, folly and warfare,” he warned.

On a purely visual level, Close Encounters is a superb film and Spielberg demonstrates once again how well he can manipulate an audience. His films may not exactly be art but they represent the peak of craftsmanship, perfect machines in which all the parts – story, actors, effects, editing, music, etc. – mesh together into a seamless whole. “Making movies is an illusion,” Mr. Spielberg once told me on the set of Poltergeist (1982), “and my job is to take that technique and hide it so well that never once are you taken out of your chair and reminded where you are.”

On a purely visual level, Close Encounters is a superb film and Spielberg demonstrates once again how well he can manipulate an audience. His films may not exactly be art but they represent the peak of craftsmanship, perfect machines in which all the parts – story, actors, effects, editing, music, etc. – mesh together into a seamless whole. “Making movies is an illusion,” Mr. Spielberg once told me on the set of Poltergeist (1982), “and my job is to take that technique and hide it so well that never once are you taken out of your chair and reminded where you are.”

The special effects were created by Douglas Trumbull, who supervised the optical effects, and Roy Arbogast, who handled the mechanical effects. Arbogast had previously worked with Spielberg on Jaws (1975), and Trumbull had worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Andromeda Strain (1971) and his own film Silent Running (1972). Close Encounters presented him with some of the toughest challenges of his career, and the optical effects alone consumed US$3.5 million out of the total budget of US$19 million. “I turned down Star Wars,” Mr. Trumbull once told me, “because I felt it was just another space opera – just an extension of the stuff I’d already done in 2001 and Silent Running – and I was totally bored with that kind of thing. I liked Close Encounters because it was a totally different look with new kinds of effects. The hardest thing about this picture was that we didn’t have the advantage of being out in space creating a fantasy. We had to be down on Earth with totally believable illusions. But putting a UFO on the screen is like photographing God – people have a very abstract mind’s-eye view of what they expect to see in a flying saucer. So the general look we went for was one of motion, velocity, luminosity and brilliance. We used very sophisticated fibre optics and light-scanning techniques to modulate, control and colour light on film to create the appearance of shape when, in fact, no shape existed.” Mr. Trumbull was so proud of his work on Close Encounters, he vowed never again to do special effects for anyone else. Instead he started work on a project of his own entitled Brainstorm (1983), a much-troubled production that suffered the sad loss of its leading lady, Natalie Wood, mid-production.

The special effects were created by Douglas Trumbull, who supervised the optical effects, and Roy Arbogast, who handled the mechanical effects. Arbogast had previously worked with Spielberg on Jaws (1975), and Trumbull had worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Andromeda Strain (1971) and his own film Silent Running (1972). Close Encounters presented him with some of the toughest challenges of his career, and the optical effects alone consumed US$3.5 million out of the total budget of US$19 million. “I turned down Star Wars,” Mr. Trumbull once told me, “because I felt it was just another space opera – just an extension of the stuff I’d already done in 2001 and Silent Running – and I was totally bored with that kind of thing. I liked Close Encounters because it was a totally different look with new kinds of effects. The hardest thing about this picture was that we didn’t have the advantage of being out in space creating a fantasy. We had to be down on Earth with totally believable illusions. But putting a UFO on the screen is like photographing God – people have a very abstract mind’s-eye view of what they expect to see in a flying saucer. So the general look we went for was one of motion, velocity, luminosity and brilliance. We used very sophisticated fibre optics and light-scanning techniques to modulate, control and colour light on film to create the appearance of shape when, in fact, no shape existed.” Mr. Trumbull was so proud of his work on Close Encounters, he vowed never again to do special effects for anyone else. Instead he started work on a project of his own entitled Brainstorm (1983), a much-troubled production that suffered the sad loss of its leading lady, Natalie Wood, mid-production.

The aliens who emerge from the mothership were designed by Carlo Rambaldi, the man responsible for the forty-foot-tall mechanical embarrassment that briefly appeared in King Kong (1976). The tall alien who smiles at Lacombe took three months to build (the child-like aliens were exactly that – children in costumes) and was animated through a combination of mechanical and hydraulic gadgets. The brief smile was achieved via artificial tendons operated by remote control. As usual, Rambaldi made excuses for his rather shoddy animatronics: “He doesn’t have a wide range of expressions, because probably very great advances in civilisation would gradually bring people to lose much of their emotional nature.” In fact, Rambaldi is responsible for some of the shonkiest monsters to appear on the silver screen: The aforementioned giant ape in King Kong, the tentacled alien in Possession (1981), the giant snake in Conan The Barbarian (1982), the giant worms in Dune (1984) and, most infamously, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). Once on-set, none of these mechanical creations ever worked properly, forcing the filmmakers to compromise during photography and editing. How he continued to get work is beyond me. I believe there’s an old Hollywood adage that states one should never work with children or animals or Carlo Rambaldi.

The aliens who emerge from the mothership were designed by Carlo Rambaldi, the man responsible for the forty-foot-tall mechanical embarrassment that briefly appeared in King Kong (1976). The tall alien who smiles at Lacombe took three months to build (the child-like aliens were exactly that – children in costumes) and was animated through a combination of mechanical and hydraulic gadgets. The brief smile was achieved via artificial tendons operated by remote control. As usual, Rambaldi made excuses for his rather shoddy animatronics: “He doesn’t have a wide range of expressions, because probably very great advances in civilisation would gradually bring people to lose much of their emotional nature.” In fact, Rambaldi is responsible for some of the shonkiest monsters to appear on the silver screen: The aforementioned giant ape in King Kong, the tentacled alien in Possession (1981), the giant snake in Conan The Barbarian (1982), the giant worms in Dune (1984) and, most infamously, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). Once on-set, none of these mechanical creations ever worked properly, forcing the filmmakers to compromise during photography and editing. How he continued to get work is beyond me. I believe there’s an old Hollywood adage that states one should never work with children or animals or Carlo Rambaldi.

And it’s with that thoughtful aphorism in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week, but not before thanking The New Yorker (November 1977), Newsweek (November 1977), Time (November 1977) and Filmmaker’s Newsletter (volume 11 issue 2) for assisting me in my research for this article. I look forward to enjoying your company again soon when I have the opportunity to give you swift kick in the old brain-box with another fright-filled fear-fest from the far side of…Horror News! Toodles!

And it’s with that thoughtful aphorism in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week, but not before thanking The New Yorker (November 1977), Newsweek (November 1977), Time (November 1977) and Filmmaker’s Newsletter (volume 11 issue 2) for assisting me in my research for this article. I look forward to enjoying your company again soon when I have the opportunity to give you swift kick in the old brain-box with another fright-filled fear-fest from the far side of…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews