SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

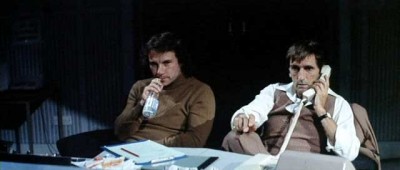

“Roddy has a camera implanted in his brain. He is then hired by a television producer to film a documentary of terminally ill Katherine, without her knowledge. His footage will then be run on the popular television series Death Watch.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

A common feature of modern dystopias is to imagine a future so devoid of natural fulfillment for ordinary people that, like vultures of the mind, they can only get sustenance from avidly devouring the disasters of others, an Orwellian/Warholian world of uninterrupted surveillance in which ordinary people become famous for fifteen minutes. The more pessimistic of our population believe we’re living in that future already. Such a future is presented in Death Watch (1980), a French film made by Bertrand Tavernier who chose – rather eccentrically – to shoot it in Glasgow because it was the nearest he could find to the city of the future. This unusual mix of sensibilities and cultures immediately gives the film an uneasy atmosphere.

The film is based on a very good science fiction novel called The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe also known as The Unsleeping Eye by British author David Compton, and remains fairly true to its original source. In the not-too-distant future, the medical profession has almost eradicated death. There is, therefore, considerable public interest in Katherine Mortenhoe – who programs computers to write romantic fiction – because she is dying of a rare disease. Roddy is an investigative television journalist who is hired to follow her without revealing his identity, and send back footage of her dying for the popular television show Death Watch. To do this without being caught, it is necessary that his eyes should be surgically modified to operate a video camera implanted in his skull.

The film is based on a very good science fiction novel called The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe also known as The Unsleeping Eye by British author David Compton, and remains fairly true to its original source. In the not-too-distant future, the medical profession has almost eradicated death. There is, therefore, considerable public interest in Katherine Mortenhoe – who programs computers to write romantic fiction – because she is dying of a rare disease. Roddy is an investigative television journalist who is hired to follow her without revealing his identity, and send back footage of her dying for the popular television show Death Watch. To do this without being caught, it is necessary that his eyes should be surgically modified to operate a video camera implanted in his skull.

As it turns out, Katherine is not really ill at all, and her symptoms are being caused by the phony medicine she has been given but, by the time we learn this, Roddy has deliberately blinded himself in a fit of guilt and she, naturally enough, commits suicide. It’s terribly downbeat in a French sort of way and, thirty years ago, was as fair to the media as Coma (1978) was to doctors. What happened to the good old days when satire depended on the subtlety of its malice?

As it turns out, Katherine is not really ill at all, and her symptoms are being caused by the phony medicine she has been given but, by the time we learn this, Roddy has deliberately blinded himself in a fit of guilt and she, naturally enough, commits suicide. It’s terribly downbeat in a French sort of way and, thirty years ago, was as fair to the media as Coma (1978) was to doctors. What happened to the good old days when satire depended on the subtlety of its malice?

The film is almost too oversensitive. So keen is director Tavernier to capture the human pathos of this vile situation that all the emphasis is on the melodramatic nuances of the romance between Roddy and Katherine, and almost no energy is expended on making this future world look believable – a rather perfunctory evocation of urban blight is simply not enough. On the other hand, much energy is spent in exploring the morbidity of a situation which is, after all, self-evidently morbid – it hardly needs to be rammed home.

The film is almost too oversensitive. So keen is director Tavernier to capture the human pathos of this vile situation that all the emphasis is on the melodramatic nuances of the romance between Roddy and Katherine, and almost no energy is expended on making this future world look believable – a rather perfunctory evocation of urban blight is simply not enough. On the other hand, much energy is spent in exploring the morbidity of a situation which is, after all, self-evidently morbid – it hardly needs to be rammed home.

Which brings me to the ingredients that really makes Death Watch worth your time – the casting. Harvey Keitel, who plays the guilt-ridden Roddy, is better known for tough-guy roles and for his parts in such films as Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), The Duellists (1977), Nemo: Dream One (1984), The Pick-Up Artist (1987), Reservoir Dogs (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994), Thelma And Louise (1991), Bad Lieutenant (1992), The Piano (1993), From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), Cop Land (1997) and Red Dragon (2002). More recently he could be found playing Lieutenant Gene Hunt in the American adaptation of the British time-slip cop show Life On Mars.

Which brings me to the ingredients that really makes Death Watch worth your time – the casting. Harvey Keitel, who plays the guilt-ridden Roddy, is better known for tough-guy roles and for his parts in such films as Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), The Duellists (1977), Nemo: Dream One (1984), The Pick-Up Artist (1987), Reservoir Dogs (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994), Thelma And Louise (1991), Bad Lieutenant (1992), The Piano (1993), From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), Cop Land (1997) and Red Dragon (2002). More recently he could be found playing Lieutenant Gene Hunt in the American adaptation of the British time-slip cop show Life On Mars.

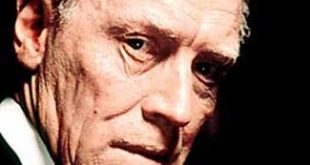

Harry Dean Stanton appeared in independent films like Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Cockfighter (1974), Escape From New York (1981) and Repo Man (1984), as well as many mainstream Hollywood productions including Cool Hand Luke (1967), Kelly’s Heroes (1970), The Godfather Part II (1974), Alien (1979), Christine (1983), Red Dawn (1984), Pretty In Pink (1986), and The Green Mile (1999). I first spotted him as a rifleman at the very beginning of Pork Chop Hill (1959) starring Gregory Peck, and he had a small role in How The West Was Won (1962) as one of Eli Wallach’s gang. His principal lead film role was as Travis Henderson in Paris Texas (1984), a role that was originally written for Sam Shepherd.

Harry Dean Stanton appeared in independent films like Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Cockfighter (1974), Escape From New York (1981) and Repo Man (1984), as well as many mainstream Hollywood productions including Cool Hand Luke (1967), Kelly’s Heroes (1970), The Godfather Part II (1974), Alien (1979), Christine (1983), Red Dawn (1984), Pretty In Pink (1986), and The Green Mile (1999). I first spotted him as a rifleman at the very beginning of Pork Chop Hill (1959) starring Gregory Peck, and he had a small role in How The West Was Won (1962) as one of Eli Wallach’s gang. His principal lead film role was as Travis Henderson in Paris Texas (1984), a role that was originally written for Sam Shepherd.

Swedish-born actor Max von Sydow has been featured in over a hundred and forty international films in many different languages including Swedish, Norwegian, English, Italian, German, Danish, French and Spanish – whew! Some of his most memorable film roles include Antonius Block in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), Jesus Christ in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), Father Merrin in The Exorcist (1973), Joubert in Three Days Of The Condor (1975), Ming The Merciless in Flash Gordon (1980), Justice Fargo in Judge Dredd (1995), Lamar Burgess in Minority Report (2002) and Doctor Naehring in Shutter Island (2010).

Swedish-born actor Max von Sydow has been featured in over a hundred and forty international films in many different languages including Swedish, Norwegian, English, Italian, German, Danish, French and Spanish – whew! Some of his most memorable film roles include Antonius Block in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), Jesus Christ in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), Father Merrin in The Exorcist (1973), Joubert in Three Days Of The Condor (1975), Ming The Merciless in Flash Gordon (1980), Justice Fargo in Judge Dredd (1995), Lamar Burgess in Minority Report (2002) and Doctor Naehring in Shutter Island (2010).

Another future veteran of Flash Gordon, Robbie Coltrane, started acting in his early twenties working in theatre and stand-up comedy. He soon moved into films, obtaining roles in a number of movies such as the above-mentioned Flash Gordon, Scrubbers (1983), Krull (1983), The Supergrass (1985), Absolute Beginners (1986), Mona Lisa (1986), The Fruit Machine (1988) and Slipstream (1989). He played Falstaff in Henry V (1989), starred with Eric Idle in Nuns On The Run (1990), played the Pope in The Pope Must Die (1991) and Mister Hyde in Van Helsing (2004), not to mention recurring roles in both the Harry Potter and James Bond franchises.

Another future veteran of Flash Gordon, Robbie Coltrane, started acting in his early twenties working in theatre and stand-up comedy. He soon moved into films, obtaining roles in a number of movies such as the above-mentioned Flash Gordon, Scrubbers (1983), Krull (1983), The Supergrass (1985), Absolute Beginners (1986), Mona Lisa (1986), The Fruit Machine (1988) and Slipstream (1989). He played Falstaff in Henry V (1989), starred with Eric Idle in Nuns On The Run (1990), played the Pope in The Pope Must Die (1991) and Mister Hyde in Van Helsing (2004), not to mention recurring roles in both the Harry Potter and James Bond franchises.

Austrian-born actress Romy Schneider, who has the tragic role of the continuous Katherin Mortenhoe, first came to my attention in Christine (1958), a remake of Liebelei (1933) which starred her own mother Magda Schneider. in 1959 Romy decided to live and to work in France, slowly gaining the interest of film directors such as Orson Welles and Luchino Visconti. Under Visconti’s direction, she gave performances in John Ford’s stage play ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore (1961) and in the film Boccaccio 70 (1962). A brief stint in Hollywood included appearances in Good Neighbour Sam (1964) and What’s New Pussycat? (1965) costarring Peter O’Toole, Peter Sellers and Woody Allen, who also wrote the screenplay.

Austrian-born actress Romy Schneider, who has the tragic role of the continuous Katherin Mortenhoe, first came to my attention in Christine (1958), a remake of Liebelei (1933) which starred her own mother Magda Schneider. in 1959 Romy decided to live and to work in France, slowly gaining the interest of film directors such as Orson Welles and Luchino Visconti. Under Visconti’s direction, she gave performances in John Ford’s stage play ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore (1961) and in the film Boccaccio 70 (1962). A brief stint in Hollywood included appearances in Good Neighbour Sam (1964) and What’s New Pussycat? (1965) costarring Peter O’Toole, Peter Sellers and Woody Allen, who also wrote the screenplay.

In a tragic turn of events, just a couple of years after completing Death Watch, Romy Schneider was found dead in her Paris apartment in 1982. At first it was suggested that she had committed suicide by taking a lethal c**ktail of alcohol and sleeping pills, but after a second post-mortem examination was carried out, authorities declared that she had passed away from natural causes aka heart attack. And it’s on that rather sad thought I’ll ask you to please join me next week so I can poke you in the eye with another frightful excursion to the backside of Hollywood, filmed in glorious 2-D black-and-white Regularscope for…Horror News! Toodles!

Death Watch (1980)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Seeing the widescreen images looks like a different film compare to the rotten pan & scan VHS release I’ve seen. Who came up with this idea? IT means you end up watching a chair or the side of someone’s face for 15 minutes… I still like Tavernier’s unfussy approach, but it’s not in the same league as another England based psychological film of the mid-70s, THE OFFENCE, by another outsider, Sidney Lumet. I think Lumet captures something very mundane, ugly and harrowing which is very familiar and more harrowing for that. In a way, it’s the most penetratingly British feeling film of the 70’s. Very dark, I think…

Hello, good evening and welcome! Thank you for reading. I love Sidney Lumet’s work, a very prolific director of great films, but my favourites have always been the sixties films Fail-Safe, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, The Pawnbroker and others. Admittedly, I’m a big fan of early American TV, from the live teleplays of the forties/fifties to anthology shows like Twilight Zone and Outer Limits.

It says in the above article that Romy’s character “…naturally enough, commits suicide.” She’s been told she isn’t dying after all, so her suicide isn’t as natural as it is tragic. Katherine feels betrayed by everyone around her, even her doctor, not, this time, by life itself as she was cruelly led to believe.

It says in the above article that Romy’s character “…naturally enough, commits suicide.” She’s been told she isn’t dying after all, so her suicide isn’t as natural as it is tragic. Katherine feels betrayed by everyone around her, even her doctor, not, this time, by life itself as she was cruelly led to believe.