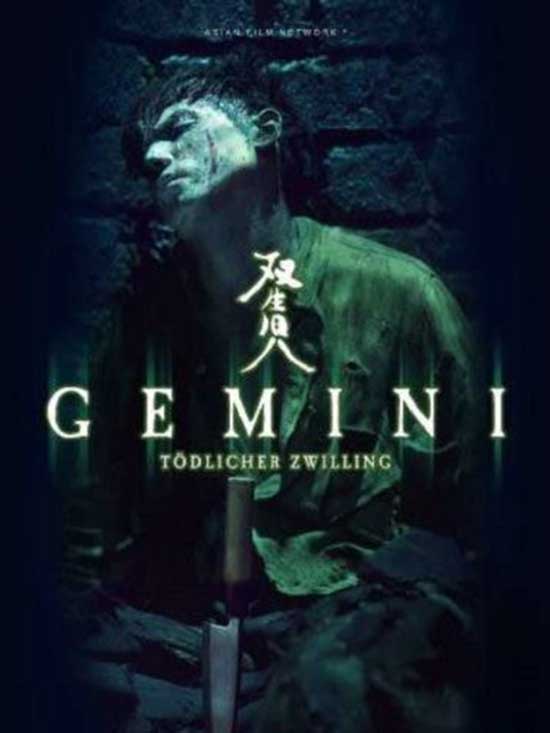

SYNOPSIS:

A successful doctor, Yukio’s picture perfect life is gradually wrecked, and taken over by his avenging twin brother, who bumps off his family members one by one and reclaims his lover who is now Yukio’s wife.

REVIEW:

Shin’ya Tsukamoto’s mystery drama Gemini breaks away from the master filmmaker’s customary conventions, but still maintains the same ferocious style and atmosphere that can be found at the heart of all his films. It’s bold, fierce, utterly beautiful and a great watch for any Tsukamoto fans.

The story focuses on a successful doctor Yukio (Masahiro Motoki) whose life is thrown off course when a long-lost twin returns to reclaim his old lover and on the way wrecks Yukio’s life as best as he can.

As stated, on the surface Gemini is a big deviation from the typical Tsukamoto style. Not only is it shot in bold, beautiful colours, but it bears no hints of the modern-day horrors most fans are used to seeing and instead takes the story to a period setting. The Meiji-era costumes and sets seem miles away from the harsh industrial imagery he is so well known for and the softly lit imagery something completely removed from the usual striking monochromes. However, you do not have to get too far into the film to start seeing the hallmarks of a Tsukamoto film. The intensity, the chaos, people having their lives ripped apart by an outside force, are all familiar from his larger catalogue and even in this unusual setting, still executed with the same style and kinetic energy.

Gemini takes its inspiration from a short story called Twins by the master of Japanese mystery literature, Edogawa Ranpo. While Ranpo’s earlier works focused more on the process of crime solving, in the 1930’s he moved on to more unusual waters, tackling gruesome and bizarre subject matters, such as a sculptor/serial killer looking for the perfect model with deadly results (Blind Beast), and a story of a man hiding inside of chair as he wants to feel the weight of people sitting on him (The Human Chair). Many of these stories include an element of obsession with mundane things turning into all-compassing fixations taking over the protagonist life, as well as the element of the uncanny: the idea of something completely normal and everyday turning somehow sinister. The idea of doppelgangers and evil twins also feature in this context, often with the twin or a look-alike taking over someone’s life, either to gain wealth and status or to pursue revenge.

It is not at all surprising that Tsukamoto would undertake adapting one of Ranpo’s stories. The thematic similarities between the two men’s work are striking and even though Tsukamoto’s work is largely concerned with issues stemming from more modern sources, the same basic elements are there. Similar to Ranpo, Tsukamoto has repeatedly explored the humdrum of everyday turning into complete chaos. The themes of obsession feature heavily throughout his work, with the main protagonist’s lives being consumed by obsessive thoughts and behaviours that often ultimately end up being their demise. Tetsuo (1989), Tokyo Fist (1995), Bullet Ballet (1998) and A Snake of June (2002) all feature a single minded fixation of some kind, all of which have been forced to the protagonists life by something or someone outside of their everyday world, leading theirs lives down a (often, but not always) destructive new path.

While the style of the film may initially seem quite different from the usual Tsukamoto tropes, the same old tricks soon make an appearance amongst the sedate period drama. In a dramatic flashback scene between Yukio’s Wife Rin (Ryô) and her ex-lover Sutekichi (also played by Masahiro Motoki), the pairs passion for each other is depicted in the anarchic manner that is so familiar from Tsukamoto’s earlier works. Motoki does a sublime job in the double role, balancing between the sensible doctor, his maniacal doppelganger and somewhere in between as the two personalities seem to switch places.

The once cold and haughty doctor turns into a wild savage filled with hatred but perhaps also a touch of newly found humility, while the vengeful Sutekitchi slides into the role of apparent sophistication but simultaneously takes on his brother’s frigid nature. In the middle remains Rin, the woman both want for their own and who is not only torn between the two men but also her past and present self. Ryô with her ethereal presence is perfectly cast in the role and gives an engaging and beautifully intense performance. Chu Ishikawa’s mournful soundscape offers a fitting backdrop for the story, changing from more melodic tunes into a wild and hard-hitting industrial sound, deeply reminiscent of the soundtracks he has composed for Tsukamoto in the past. The director himself is also responsible for the editing and cinematography which manifests itself with familiarly hectic cuts and camera work that mirrors the turmoil of the story, giving the film an eccentric but very captivating rhythm.

There is a certain dreamlike quality to Gemini that can also be found in other Tsukamoto productions. Even though from the context of the Ranpo story we can clearly place the story in a certain era, with the clever use of set, lighting and costume design, Tsukamoto has once again created a story that seems to be removed from this reality and lives in a time and place of its own. The more traditional shots fitting to any period drama work side by side with scenes lit boldly with vibrant blues and reds, and the customary clothing of Yukio and his household are contrasted by the wild, theatrical clothing of Sutekitchi and the people of the slums which have no place in historical accuracy. Actors without eyebrows, hairstyles resembling flying saucers and nurses dressing in futuristic plague doctor outfits all help cement the ambiguous atmosphere even further, creating something truly unique.

Gemini is an absolute much watch for any Tsukamoto fans, but I would happily also recommend it to anyone interested in Ranpo adaptations, or if you just want a slightly different kind of costume drama. It’s an encaptivating exploration of duality, societal inequity and what we define as “civilised” behaviour, all delivered in a trademark Tsukamoto style.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews