Originally this installment was going to cover 1968’s TARGETS and 1931’s M. But these were too hefty for one piece so we’ll just stick with Targets—an overlooked film that you must see, inspired by a nightmarish event we shouldn’t forget.

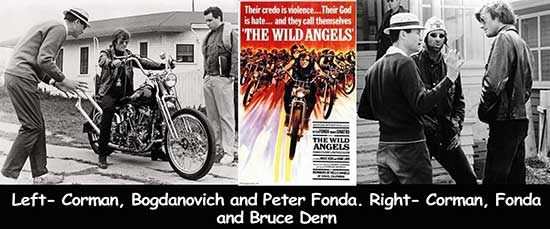

In 1966, Peter Bogdanovich was a film critic and cinema junkie with visions of directing. A chance meeting with producer/director Roger Corman turned that dream into a reality. Impressed with one of Bogdanovich’s Esquire Magazine articles, Corman took the young man under his wing. Bogdanovich’s first assignment was rewriting the screenplay for Corman’s 1966 biker classic The Wild Angels. Bogdanovich restructured the original exploitation film script, giving it the feel of Italian neorealist films like Nights of Cabiria (1957). This gritty docudrama approach was fairly radical for a Hollywood film. As a result, critics were split, some deeming The Wild Angels a realistic slice of an American subculture while others just wanted to take a shower to wash away the experience. Either way The Wild Angels is entertaining as hell and earned Bogdanovich his seat in the director’s chair.

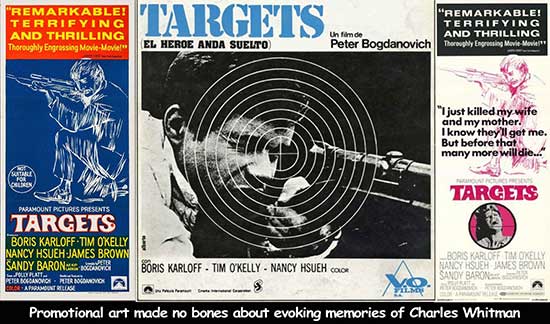

Within months he was writing and directing Targets (1968), the tale of a fading horror movie star named Byron Orlock (Boris Karloff) who crosses paths with deranged Vietnam veteran Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly). Karloff gives a virtuoso performance, but Targets truly comes alive when we enter Bobby’s crumbling world. Bobby Thompson introduced audiences to an entirely new kind of monster—the clean-cut boy next door who’s secretly harboring terrible thoughts. Bobby’s such an iconic American boy that he even sips a bottle of Coke and eats white bread sandwiches while slaughtering innocents through a telescopic site.

Despite a limited budget, first time director Bogdanovich handles the fine details with all the finesse of a veteran filmmaker. The strikingly bland décor of Bobby’s home is a great example—there are no books, art or human warmth on display, just too many guns and a constantly yammering television. It’s a perfect visual window into Bobby’s empty soul.

The resulting film was so powerful that Corman managed to sell the distribution rights to Paramount, turning an instant profit. Bogdanovich went on to a directorial career of amazing highs like The Last Picture Show (1971) and Paper Moon (1973) along with epic but fascinating lows like 1975’s At Long Last Love.

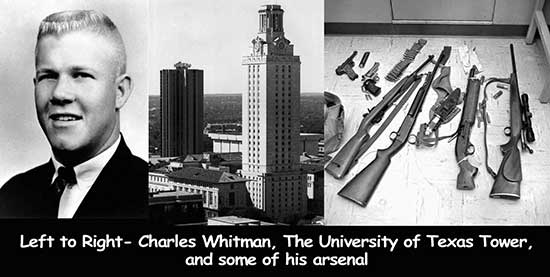

But Targets’ hometown boy turned psychopath wasn’t just the product of Bogdanovich’s imagination. On August 1st 1966, Charles Whitman, a Marine Corps veteran and former Eagle Scout, went on a one-day killing spree resulting in the deaths of sixteen people. After murdering his wife and mother Whitman entered the University of Texas where he killed three more people. He then climbed atop the university’s tower carrying an arsenal of high-powered rifles. From this high vantage point he slaughtered eleven pedestrians and wounded thirty-one others before being gunned down by police officers.

At the time it was the worst mass murder in American history. While searching Whitman’s house police found a typed multi-page suicide letter sealed in an envelope. On the outside of the envelope he’d written, “I never could quite make it. These thoughts are too much for me.” The public struggled to find the wherefore and why of this senseless bloodbath, but all they came up with was, to quote the San Antonio Express, “The same non-answer: something snapped.”

Doctors even did a post-mortem study of Whitman’s brain, searching for some answer. Although they found a pecan-sized tumor, most medical experts discount the idea that it turned him into a mass murderer. In truth, Whitman’s violent tendencies had been brewing for many years.

To friends Whitman had seemed textbook normal. He’d been an exemplary Marine, although, unlike the character in Targets, he never saw combat. He was well liked and was considered a practical joker who occasionally said odd things. Once, while looking up at the University of Texas Tower, he chillingly commented to friends that, “A person could stand off an army from up there before they got him.”

But Whitman’s normalcy was only skin deep. Prior to his killing spree he’d been plagued by mental illness, committed domestic violence, harbored murderous fantasies and was wracked by psychosomatic headaches. Whitman was aware that he was potentially dangerous and even kept extensive journals of his thoughts. On the day of the murders he wrote, “I do not really understand myself these days. I am supposed to be an average, reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I cannot recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts.” The warning signs were all there—the problem was that back in 1966 nobody knew how to read those signs or wanted to admit mental illness existed. Whitman even went to university psychiatrist Dr. Maurice Heatly, confessing his desire to climb the Texas University Tower and use his military sniper training on innocent people. The doctor didn’t take Whitman seriously and even after the shooting claimed Whitman showed “no psychosis symptoms at all.”

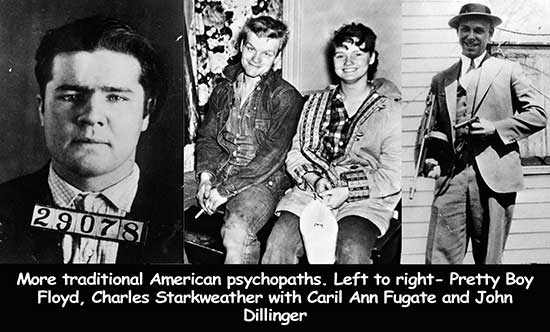

Whitman’s explosion of violence ripped apart the fabric of American society. The country had seen some horrible killers in the past. Back in the 1930s, criminals like John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson callously gunned down police and citizens alike, but these were depression-era bank robbers, more myth than men. In 1958, Charles Starkweather had gone on a month long, eleven victim killing spree, but he was a white trash delinquent with a fourteen-year-old girlfriend.

Whitman, on the other hand, was a former altar boy, an Eagle Scout and a US Marine—three bastions of virtue and honor. He had a crew cut, wore pressed chino pants and always mowed his lawn. Suddenly Americans were forced to admit that real monsters didn’t live in gothic castles or under children’s beds—in truth, they could be standing in line right next to you at the grocery store.

People were shocked by Charles Whitman’s rampage, but, as is often the case, we didn’t learn anything. Today, guns are more prevalent than ever, mental illness is still a stigma we keep in the shadows and mass murder explodes across cities and campuses with soul-numbing regularity. Prior to Whitman there had never been a mass shooting in America with ten or more victims. Since Whitman there have been at least twenty-seven incidents. Targets stands as a potent reminder that America has been plagued by mass shootings for over fifty years. Each time we still hear, “the same non-answer: something snapped.” That’s probably easier than facing the societal wide truth—something’s broken.

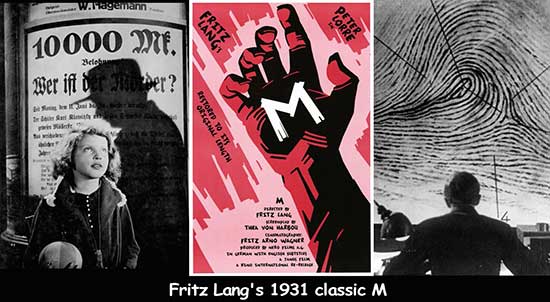

Next time we’ll take a look at Fritz Lang’s 1931 classic M, the film that invented both the serial killer genre and the police procedural. But the grisly true story behind M is rooted in the collapse of Germany’s Weimar Republic, the rise of Nazism and the depths of a psychotic mind.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews