SYNOPSIS:

During a rural summer picnic, a few students and a teacher from an Australian girls’ school vanish without a trace. Their absence frustrates and haunts the people left behind.

REVIEW:

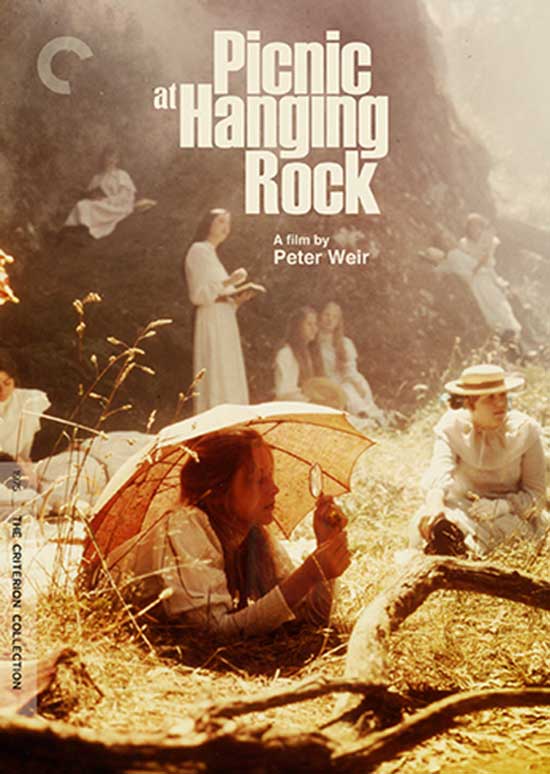

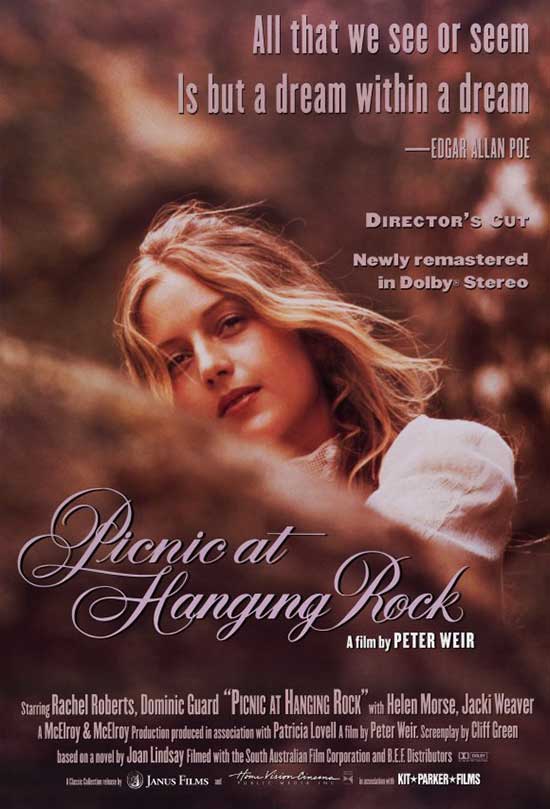

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), directed by Peter Weir from a script written by Cliff Green, based on the novel of the same name by Lady Joan Lindsay; starring Rachel Roberts, Anne-Louise Lambert, and Vivean Gray.

This film, which launched the career of Australian director Peter Weir (The Truman Show-1998; The Year of Living Dangerously-1982), is one of those that are hard to fit into a genre. The best I can do is call it a drama with supernatural overtones. It has its creepy and mysterious moments, and people who like creepy and mysterious plots tend to like it. People who dislike slow-burners, period drama, and overt horror will probably hate it. It is a very famous film that often turns up on various “best of” lists.

Based on one of the most acclaimed novels in Australian literature, Picnic is a brooding, enigmatic meditation on European colonialism and the nature of female freedom, wrapped up in a lacy Victorian pinafore. Many critics have described it as “haunting.”

The plot concerns an Australian girls’ school in 1900, the last year of Queen Victoria’s epochal reign. The school, with manicured green lawns and luxurious flowerbeds, sits incongruously on the fringes of wild bush country, three hours by horse from an ancient, volcanic outcropping called Hanging Rock. The school is owned and operated by Mrs. Appleyard, an English widow of 57, who was forced to emigrate to Australia to find a means of support after the death of her husband: Mrs. Appleyard clearly resents every minute of her reduced circumstances.

The story begins on the morning of Valentine’s Day (which, because it’s “down under,” falls on a sunny summer day, instead of in the winter.) The girls, who range in age from 13 to 18, are getting ready for their upcoming picnic later in the day to Hanging Rock.

As upper-class girls of their time, they dress in ruffled white linen dresses, white gloves, straw hats, and pack along lacy, flimsy parasols–completely impractical for a rugged area known for venomous snakes and poisonous ants. The cinematographer, Russel Boyd, does a fantastic job of contrasting the massive, twisted volcanic structures (with many of them suggesting giant faces) with the unpractical and clueless attire of the Victorian picnickers.

They have their picnic, and then four of the girls break away to explore the rocks. Their math teacher, Miss McCraw follows shortly afterward, embarking on an exploration of the rocks on her own.

Only one of the girls returns–a fat, unlikeable girl called Edith—and Edith runs back to the picnic site screaming hysterically, but is unable to say what frightened her. The other three girls and the math teacher have disappeared without a trace. Further compounding the mystery, eight days after the picnic, one of the missing girls is found unconscious on the rock, somehow surviving in the open for more than a week without food or water. She has no memory of what happened.

The disappearances ruin the school’s reputation, and Mrs. Appleyard starts to break down mentally, with dark consequences for one of the remaining girls at the school–and for herself. All of which is stunningly filmed in gorgeous cinematography by Boyd, who many years later would win an Oscar for another famous Weir film, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003).

The mesmerizing score features both Beethoven and a creepy pan flute played by Zamfir the Pan Piper (his music was ubiquitous on cable television in the late ‘70s.) British stage actress Roberts plays the steely Mrs. Appleyard and quickly dominates the film like a pro. There is a lot of symbolism which is debated on film forums, much in the same way as other heavily symbolic films are, such as Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) or Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958).

For example, whenever Miranda, the leader of the missing girls, is pictured, thought about or spoken about, the image of a swan almost always appears in the frame somehow. Miranda is also named for the virtuous daughter in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. There’s a vague suggestion throughout both the book and the film that Miranda doesn’t belong in this world, which makes her disappearance into the ether somewhat explainable. Meanwhile, Mademoiselle, the French teacher, who symbolizes sex and voluptuousness, is called Diane de Poitiers—literally the name of a famous 16th Century courtesan. The unfortunate math teacher, Miss McCraw, has a name that can be taken possibly as a reference to a crustacean—which, considering what may have happened to her, is entirely fitting.

There are many mysteries in Picnic, not just the vanishing of the girls and their teacher, and most of them are not really explained. The author of the novel, Joan Lindsay, was hounded for the rest of her life by fans determined to make her provide an explanation, which she never did. However, after her death in the 80s, a missing chapter of the book was published, which does explain what happened after a fashion, called The Secret of Hanging Rock. It ties up some loose ends, although it also raises more questions than it answers. If, after viewing this film, you absolutely have to know the explanation, you can buy a Kindle version of the missing chapter on Amazon for $3.

NOTE ON THE DVD: The U. S. DVD version released by Criterion had seven minutes chopped out of it by Weir when it was issued in 1998. The most accessible way for U. S. viewers to see the original theatrical cut may be a 1990 VHS version purchased from a third-party vendor, but I haven’t seen that version so I can’t comment for sure.(It’s for this very reason that some of us still have VHS players!)British film fans can buy a DVD set with both versions.

9/10

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews