SYNOPSIS:

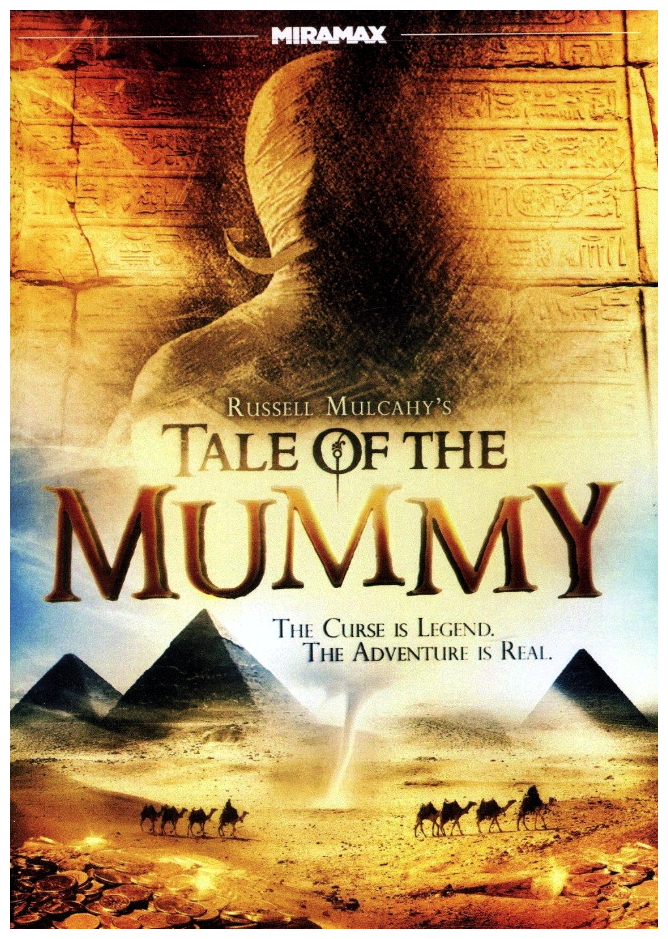

“Centuries ago, under the sands of ancient Egypt, a prince was buried and his tomb eternally cursed so that no man would ever again suffer from his evil ways. But hundreds of years later on a greedy search for treasure, a group of archaeologists break the curse’s seal of the tomb. Every man vanishes without a trace, leaving behind only a log book and a deadly warning of the legend of the bloodthirsty Talos. Fifty years later the log book ends up in the hands of the granddaughter of the head archaeologist, and she defiantly sets out to retrace his steps. Discovering the forbidden treasure, she recovers a sacred amulet and once again unleashes the savage power of the tomb. Racing through the streets of London, and against the force of a rare interplanetary lineup she, along with the help of her original dig team and an American detective, desperately try to turn back the inhuman curse and to keep Talos from destroying all in his path in an attempt to gain immortal power.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Mummies! Tales of undead creatures wrapped in bandages were originally inspired by the horrific process of mummification practiced by ancient Egyptians and other past civilisations. During the last century, horror films and other mass media popularised the notion of a curse associated with mummies, and the 1922 discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by archaeologist Howard Carter brought mummies into the mainstream. The belief in cursed mummies is a relatively modern myth stemming from the supposed curse on the tomb of Tutankhamun, and one of its earliest appearances was in The Jewel Of Seven Stars, a horror novel by Bram Stoker published in 1903 that concerned an archaeologist’s plot to revive an ancient Egyptian mummy. Films propagating such beliefs include the original Universal movie The Mummy (1932) starring Boris Karloff as Imhotep (which spawned four sequels featuring a mummy named Kharis) and the Hammer horror reboot of The Mummy (1959) starring Christopher Lee as Kharis (which spawned three sequels starring various actors as different mummies). The next three decades represented a long dry spell for the bandaged bad-boy, until the mid-nineties when zombies were becoming terribly popular (some might say over-used) in Hollywood. Strangely enough, Australian filmmaker Russell Mulcahy was all bandaged up himself when he got the idea for his mummy project.

“I went skiing and broke my leg so I was stuck in a wheelchair for about three months and, instead of moping around, I thought, well, hang on, why don’t I write a screenplay? I got together with some friends and we thought, what genre hasn’t really been redone or remade for quite a while? I mean, vampires and Frankenstein have both been done recently, and mummies came to mind. I thought it was time to do a different telling of the mummy story, a reinvention of it and, with today’s technology, we could give it a whole new slant. The new slant is, what happens if you open up a tomb and there’s no mummy? But all the wrappings are there, just lying there. Basically, the premise is the wrappings contain the evil. The wrappings can fly around town, they can form into a nine-foot mummy, they can wrap you up and crush you. What we didn’t want to do was the classic three-thousand-year-old dusty old man wandering around with bandages trailing behind him.” The ‘we’ he’s referring to include screenwriters Keith Williams and John Esposito, fresh from the exciting Quentin Tarantino/Robert Rodriguez vampire action adventure From Dusk Till Dawn (1996).

Tale Of The Mummy (1998) begins in Egypt in 1948, when an archeological team led by Richard Turkel (Christopher Lee) reaches the tomb of Talos, which is apparently cursed. The hieroglyphics at the entrance warn that all should avoid the place as it has been abandoned by all that is holy. Despite this, they proceed to open the chamber’s door only to be blasted with a cloud of dust, which causes the structure to crumble apart. Turkel manages to blow the tomb shut, killing himself in the process. Fast-forward to 1999, Turkel’s granddaughter Samantha (Louise Lombard) is picking up where he left off. When she and her team (Sean Pertwee, Gerald Butler, Lysette Anthony) break into the burial room, they find the sarcophagus of Talos suspended from the ceiling. One of the team has a seizure while experiencing the atrocities of Talos, and another falls to his death. Fast-forward again another nine months, we find the sarcophagus in a container in the British Museum when a power outage occurs. The container is broken into, a guard is killed, and police detective Riley (Jason Scott Lee) warns them that the killer will undoubtedly strike again. Soon after, a youth is attacked by Talos (Roger Morrissey) in a bathroom and his body is unceremoniously dragged into a toilet.

While Samantha is telling Riley all about the myth of Talos, another man is attacked in the car park but, in the meantime, we learn that Talos had insisted that his bodily organs be removed and consumed by his followers, so that he could someday be resurrected to reclaim them, gaining physical perfection and immortality. You see, young Talos (Enzo Junior) was exiled from Greece for practicing sorcery and travelled to Egypt where he falls in love and, in a pagan ceremony, marries the Pharaoh’s daughter Princess Nefrianna (Waris). Neighbouring factions of Egypt order the Pharaoh to destroy the sorcerer, as all who opposed him were struck down with disease or tortured into believing his teachings. So, in order to save Nefrianna, the Pharaoh tells her of his plan to execute Talos, and she in turn tells Talos. When the Pharaoh’s men are sent to kill the sorcerer, they witness Nefrianna eating the heart of Talos. Bradley (Sean Pertwee) surmises that the murder victims are actually reincarnations of the Pharaoh’s servants and that killing Samantha (Nefrianna’s reincarnation) is the only way to stop Talos, who plans to be reborn when the planets align. A reborn Talos tracks Samantha to her apartment, but she manages to get away, only to be recaptured by the sorcerer posing as a dog.

“It’s an ensemble cast with everyone from Christopher Lee, Honor Blackman, Michael Lerner, Jason Scott Lee, Shelley Duvall, I even pulled in people from Highlander (1986) like John Polito, who was one of the detectives in it. In fact, it’s about forty years since Christopher made his Mummy (1959) which I think still holds up in its own charming way. I’m a huge fan of Mister Lee’s and including him was definitely a nod in that direction. He’s in the film for maybe twelve minutes. When I handed him the script he said, ‘The Mummy? Good God, you don’t expect me to get back into those bandages?!’ I said, ‘No, no, you’re the good guy this time, but he has a good death scene.’ It was made for around US$6 million. By today’s standards that’s very low. I just called up some old mates and said come and do this film. They read the script, they loved it, and we went off and had good fun for five weeks. I’m my own worst critic because I’d rate Razorback (1984) as my best. I would put it up there with Highlander (1986). It could have done with an extra five million. Hell, it could have done with an extra $500,000! There are some moments I look at and cringe, but it was one of these films I just had to get out of my system.”

Unfortunately, Mulcahy was not the only filmmaker in Hollywood trying to get a new mummy movie off the ground. Stephen Sommers, director of the action-packed horror-comedy Deep Rising (1998) had been mulling over a new take on the old monster since 1993 and in 1997 he pitched his movie, “As a kind of Indiana Jones or Jason & The Argonauts, with the mummy as the creature giving the hero a hard time.” Universal executives liked this idea so much that they approved the concept and increased the budget from US$15 million to US$80 million. The Mummy (1999) was a blockbusting box-office success followed by two inferior (yet very successful) sequels – The Mummy Returns (2001) and The Mummy III Tomb Of The Dragon Emperor (2008) – as well as a rather entertaining swashbuckling spin-off entitled The Scorpion King (1992) starring Dwayne Johnson. Needless to say, the existence of Russell Mulcahy‘s Tale Of The Mummy (1998) was somewhat lost in the media acclaim of the Sommers movie.

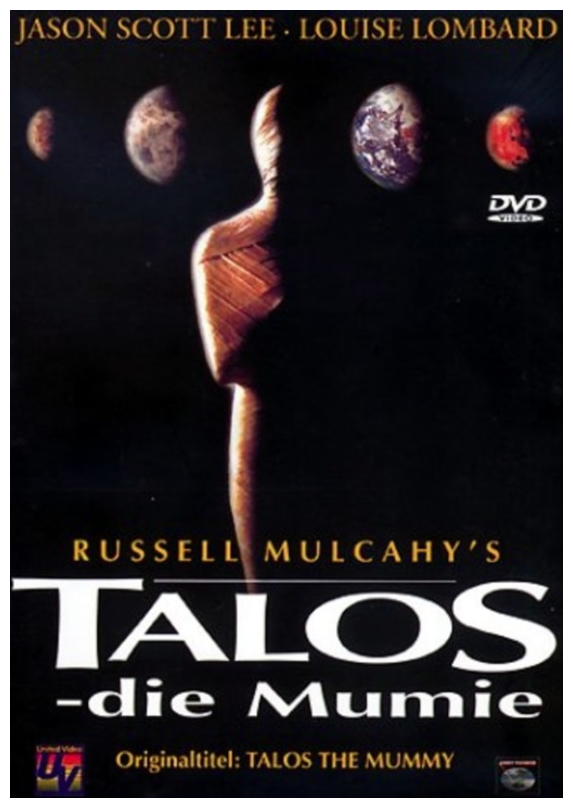

This is a pity, because Tale Of The Mummy – known in some countries as Talos The Mummy – is a fine effort from a stylistic filmmaker and has some exemplary moments: several exciting attacks; a nice scene at the police station; an encounter at a motel followed by a chase; and further exciting encounters in a subway and a parking garage. The best scene is arguably the film’s opening – the atmosphere is spooky, the setting is perfectly creepy with the usual business about a curse and the decorations used around the chamber. Once the curse is mentioned, all hell breaks loose as the brutality of Talos emerges. Then, segueing into scenes of the later expedition, that same spooky atmosphere prevails. The mummy as a monster presented here is rather fascinating. Instead of being the slow lumbering type, this mummy gets around pretty quickly, and has a couple of additional powers that set him apart from your average bandaged bad guy. He’s essentially made of gauze, meaning he can catch a breeze and fly about, not only a clever concept but also visually impressive (there’s a good reason why Mulcahy’s music videos are amongst the best remembered of the eighties).

The bandages act like tentacles, unraveling to catch and cocoon victims, and there’s a larger-than-expected body-count. Although a couple of the deaths are quite gory, most occur off-screen or just drag the victim away leaving sounds as the only clue that something nasty is happening. Another problem with Tale Of The Mummy is it seems that Mulcahy and friends forgot to write an ending, and the end result is more than a little odd and a tad confusing. The specific guidelines required to perform the all-important ceremony are not made clear, for instance, and there’s a twist in the tale that, for me, doesn’t quite work. There might be a perfectly good reason for this, as there are two versions available. I viewed the 88-minute version, only to discover since that there’s a 115-minute version available for the international market! Bottom line? While not exactly ‘top-shelf’ this Tale Of The Mummy should please any fan of the genre, just make sure you see the 115-minute version. “Despite her faults, everyone still loves their Mummy.” It’s with this joyful thought in mind I’ll quickly ask you to please join me again next week when I shall discuss another dubious classic for Horror News. Until then, good night and remember, as my old friend Bela Lugosi would say, “Bevare! Bevare of the big, green dragon that sits on your doorstep, and the gifts it leaves on your lawn.” Toodles!

Tale Of The Mummy (1998)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews