SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Vincent Vega and Jules Winnfield are two hitmen on the hunt for a briefcase whose contents were stolen from their boss, Marsellus Wallace. They run into a few unexpected detours along the road. Marsellus is out of town, and he’s ordered Vincent to take care of his wife, Mia. That is, take her out for a night on the town. Things go smoothly until one of them makes a huge error. Butch Coolidge is a boxer who’s been approached by Marsellus and been told to throw his latest fight. When Butch ends up killing the other boxer, he must escape Marsellus. Pumpkin and Honey Bunny (not their real names) are two lovebirds/thieves who have decided to rob the restaurant they’re currently eating at. But the restaurant doesn’t turn out to be as easy as the other places they’ve robbed.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Hard-boiled pulp fiction (the pulp referred to what happened to the paper after the disposable piece was read) first appeared in the United States during the twenties in such magazines as Black Mask, Spicy Stories, Ace-High, Amazing, Astounding, Detective Magazine, etc. and directly inspired the thirties cycle of gangster movies, which began with Mervyn LeRoy‘s Little Caesar (1931) and William Wellman‘s Public Enemy (1931), and culminated in the doom-laden but visually poetic forties and fifties Noir cycle. Its principal literary progenitors and adherents include Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Donald Westlake, Mickey Spillane, Elmore Leonard, and their tight no-nonsense style of writing, which concentrated on the ordinary man and woman caught up in the toils of fate. This proved enormously influential in both visual and verbal terms to the history of American cinema and, through that medium, to the history of European cinema as well.

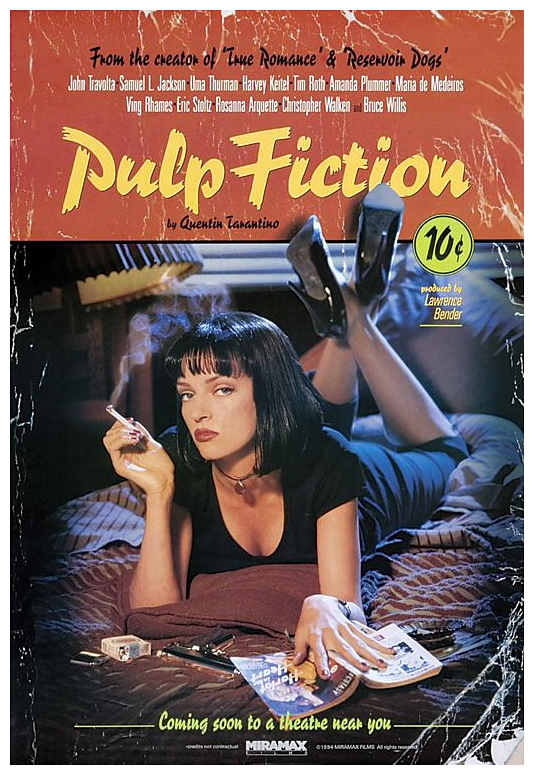

Fast-forward to the nineties and the release of Quentin Tarantino‘s first feature film Reservoir Dogs (1991), a ‘sleeper’ if there ever was one. Nobody had heard of the director and although the poster, title and cast seemed intriguing, they conveyed little. It was very much a word-of-mouth success, but Tarantino’s quirky knowing style of film-making, brilliant direction of actors, imaginative use of popular music, extreme language and violence meant that a follow-up had to really deliver. Three years later Tarantino did so in abundance, with Pulp Fiction (1994). The title alone sums up Tarantino’s interests, and he provides definitions of ‘pulp’ at the beginning. In three separate but carefully intertwined stories, sandwiched between a prologue and an epilogue during a punk robbery in a diner, Tarantino takes us through an enormous cast of low-life characters and brilliantly sustained time-shifts as he welds his material into a seamless whole. It’s not unlike Arthur Schnitzler‘s La Ronde (1950) on speed, set in a tawdry Noir Los Angeles.

Fast-forward to the nineties and the release of Quentin Tarantino‘s first feature film Reservoir Dogs (1991), a ‘sleeper’ if there ever was one. Nobody had heard of the director and although the poster, title and cast seemed intriguing, they conveyed little. It was very much a word-of-mouth success, but Tarantino’s quirky knowing style of film-making, brilliant direction of actors, imaginative use of popular music, extreme language and violence meant that a follow-up had to really deliver. Three years later Tarantino did so in abundance, with Pulp Fiction (1994). The title alone sums up Tarantino’s interests, and he provides definitions of ‘pulp’ at the beginning. In three separate but carefully intertwined stories, sandwiched between a prologue and an epilogue during a punk robbery in a diner, Tarantino takes us through an enormous cast of low-life characters and brilliantly sustained time-shifts as he welds his material into a seamless whole. It’s not unlike Arthur Schnitzler‘s La Ronde (1950) on speed, set in a tawdry Noir Los Angeles.

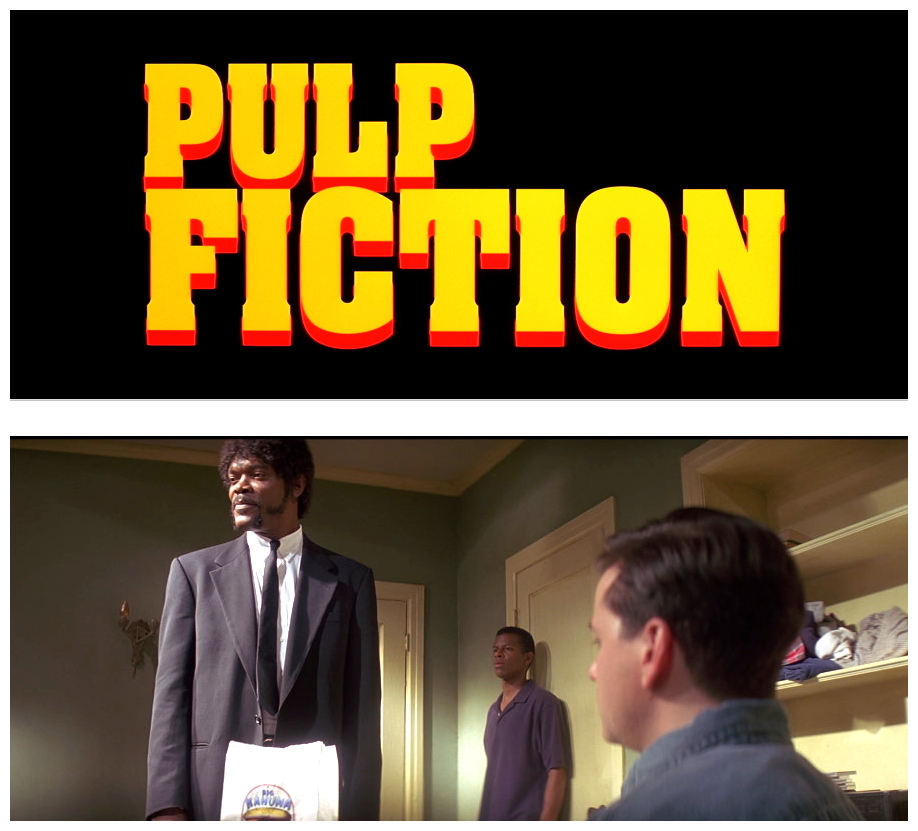

Story one involves two mob hit men, Vincent (John Travolta) and Jules (Samuel L. Jackson), who settle a score with a loser drug-dealer while discussing the merits of fast food and biblical texts. Their job goes horribly wrong and they need to call in a professional ‘cleaner’ known only as ‘The Wolf’ (Harvey Keitel) to clear up the mess. Story two concerns Butch (Bruce Willis), a boxer on the downhill slide who fails to deliver on a rigged fight and, realising that the mob will be after him, needs to get out of town fast with his girlfriend. (Maria de Medeiros). The escape plan backfires as Butch returns to his apartment to collect his much prized heirloom, a gold watch, and he crosses paths with mob boss Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames). They both end up in a very tricky situation. Story three brings us back (or forward) to Vincent again, being ordered to take vengeful mob boss Marsellus’s crazy wife (Uma Thurman) out for a night on the town. Yet again, everything goes horribly wrong.

Story one involves two mob hit men, Vincent (John Travolta) and Jules (Samuel L. Jackson), who settle a score with a loser drug-dealer while discussing the merits of fast food and biblical texts. Their job goes horribly wrong and they need to call in a professional ‘cleaner’ known only as ‘The Wolf’ (Harvey Keitel) to clear up the mess. Story two concerns Butch (Bruce Willis), a boxer on the downhill slide who fails to deliver on a rigged fight and, realising that the mob will be after him, needs to get out of town fast with his girlfriend. (Maria de Medeiros). The escape plan backfires as Butch returns to his apartment to collect his much prized heirloom, a gold watch, and he crosses paths with mob boss Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames). They both end up in a very tricky situation. Story three brings us back (or forward) to Vincent again, being ordered to take vengeful mob boss Marsellus’s crazy wife (Uma Thurman) out for a night on the town. Yet again, everything goes horribly wrong.

Is it a thriller? Yes, there’s plenty of tension, but it is undercut by absurdity. Is it a crime film? Yes, everyone has criminal intentions. But at heart it is actually one of the finest black comedies ever produced in the United States with a terrific cast that also includes Tim Roth, Rosanna Arquette, Amanda Plummer, Eric Stoltz, Steve Buscemi and Christopher Walken. Controversial issues concerning drug use, violence and sado-masochism gave the film a certain notoriety (the Wikipedia listing is quite extensive with a ginogorous list of references). In a well-known speech in May 1995, presidential candidate Bob Dole attacked the American entertainment industry for peddling nightmares of depravity, citing the Tarantino-scripted True Romance (1993) and Natural Born Killers (1994) and, in September of the same year, Dole accused Pulp Fiction of promoting heroin use.

Is it a thriller? Yes, there’s plenty of tension, but it is undercut by absurdity. Is it a crime film? Yes, everyone has criminal intentions. But at heart it is actually one of the finest black comedies ever produced in the United States with a terrific cast that also includes Tim Roth, Rosanna Arquette, Amanda Plummer, Eric Stoltz, Steve Buscemi and Christopher Walken. Controversial issues concerning drug use, violence and sado-masochism gave the film a certain notoriety (the Wikipedia listing is quite extensive with a ginogorous list of references). In a well-known speech in May 1995, presidential candidate Bob Dole attacked the American entertainment industry for peddling nightmares of depravity, citing the Tarantino-scripted True Romance (1993) and Natural Born Killers (1994) and, in September of the same year, Dole accused Pulp Fiction of promoting heroin use.

Pulp Fiction has as much to do with real crime as Cyrano De Bergerac has with real seventeenth-century France or The Prisoner Of Zenda has with real Balkan politics. The movie is simply a form of romance whose allure is focused on the characters’ unusual dialogue. As a matter of fact, Pulp Fiction is arguably one of Tarantino’s most ‘politically correct’ films and goes against most stereotypes: There is no nudity or violence directed against women; it celebrates interracial friendship and cultural diversity; it features independent females and strong African-American characters. The scene in which Vincent and Jules accidentally kill drug-dealer Marvin (Phil LaMarr) twists the meaning of the violence cliché and makes the macho myth laughable by negating the power-trip normally glorified by standard Hollywood violence.

Tarantino has continued to create a colourfully eclectic and unusual body of work ever since. Much more of a genuine ‘movie brat’ than those of the preceding generation, and much more given to exuberant self-publicising, Tarantino’s films are littered with allusions to an extraordinary array of often obscure films, music and other popular cultural references, as well as a willingness to dwell on extraordinary, often arcane, dialogue. Jackie Brown (1997), based on Elmore Leonard‘s novel Rum Punch, is easily the best adaptation of that master crime writer’s work, and showed Tarantino’s ability to exercise self-control when necessary. Personally, I believe that Kill Bill (1993) is his best work, but time will tell.

Tarantino has continued to create a colourfully eclectic and unusual body of work ever since. Much more of a genuine ‘movie brat’ than those of the preceding generation, and much more given to exuberant self-publicising, Tarantino’s films are littered with allusions to an extraordinary array of often obscure films, music and other popular cultural references, as well as a willingness to dwell on extraordinary, often arcane, dialogue. Jackie Brown (1997), based on Elmore Leonard‘s novel Rum Punch, is easily the best adaptation of that master crime writer’s work, and showed Tarantino’s ability to exercise self-control when necessary. Personally, I believe that Kill Bill (1993) is his best work, but time will tell.

Tarantino’s scripts for Tony Scott‘s True Romance (1993) and Oliver Stone‘s Natural Born Killers (1994) shimmer with cleverness, and his involvement in the absurd vampire-fest From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) led to a long-term working relationship with director Robert Rodriguez that also produced Sin City (2005), Grindhouse (2007) and Death Proof (2007). He has since become a powerful force in Hollywood, promoting and distributing various foreign films and supporting filmmakers such as Eli Roth – Hostel (2005) – and Larry Bishop – Hell Ride (2008) – and has broken box-office records with his World War Two adventure Inglourious Basterds (2009) and his tribute to Civil War Blaxploitation, Django Unchained (2012), but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll now bid you a good night and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to put goose-bumps on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick and chumpy you could carve it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

Tarantino’s scripts for Tony Scott‘s True Romance (1993) and Oliver Stone‘s Natural Born Killers (1994) shimmer with cleverness, and his involvement in the absurd vampire-fest From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) led to a long-term working relationship with director Robert Rodriguez that also produced Sin City (2005), Grindhouse (2007) and Death Proof (2007). He has since become a powerful force in Hollywood, promoting and distributing various foreign films and supporting filmmakers such as Eli Roth – Hostel (2005) – and Larry Bishop – Hell Ride (2008) – and has broken box-office records with his World War Two adventure Inglourious Basterds (2009) and his tribute to Civil War Blaxploitation, Django Unchained (2012), but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll now bid you a good night and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to put goose-bumps on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick and chumpy you could carve it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews