SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“After a harrowing ride through the Carpathian mountains in eastern Europe, Renfield enters castle Dracula to finalise the transferal of Carfax Abbey in London to Count Dracula, who is in actuality a vampire. Renfield is drugged by the eerily hypnotic count, and turned into one of his thralls, protecting him during his sea voyage to London. After sucking the blood and turning the young Lucy Weston into a vampire, Dracula turns his attention to her friend Mina Seward, daughter of Doctor Seward who then calls in a specialist, Doctor Van Helsing, to diagnose the sudden deterioration of Mina’s health. Van Helsing, realising that Dracula is indeed a vampire, tries to prepare Mina’s fiancée, John Harker, and Doctor Seward for what is to come and the measures that will have to be taken to prevent Mina from becoming one of the undead.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Dracula is the near-immortal Transylvanian Count featured in Bram Stoker‘s immensely successful novel of the same name published in 1897. Like the vampire bat and the Nosferatu of Romanian legend, he feeds on blood, preferably the blood of beautiful young women such as Lucy Westenra and her friend Mina Harker (two of the novel’s several narrators). It takes all the arcane skills of vampire-hunter Doctor Abraham Van Helsing, with his deployment of crucifixes, garlic and wooden stakes, finally to defeat Dracula. The undead Count is one of the half-dozen best-known fictional characters of modern times, and has pursued a long and active career on the stage, in films, on television, in comics, advertising, merchandising, jokes and popular lore.

German director F.W. Murnau was so impressed with Stoker’s novel that he made Nosferatu: A Symphony Of Horror (1922), which remains to be one of the greatest horror films of all time. The trouble is Murnau didn’t have permission, so he simply changed the character names and locales in the script. Harker became Hutter, Dracula became Orlok, England 1890 became Germany 1830, etc. But when the film was translated for English-speaking audiences, the powers-that-be chose to use Bram Stoker’s original familiar character names, but in the process a few typos occurred, for instance Mina Harker becomes Ellen Hutter becomes Nina Harker.

German director F.W. Murnau was so impressed with Stoker’s novel that he made Nosferatu: A Symphony Of Horror (1922), which remains to be one of the greatest horror films of all time. The trouble is Murnau didn’t have permission, so he simply changed the character names and locales in the script. Harker became Hutter, Dracula became Orlok, England 1890 became Germany 1830, etc. But when the film was translated for English-speaking audiences, the powers-that-be chose to use Bram Stoker’s original familiar character names, but in the process a few typos occurred, for instance Mina Harker becomes Ellen Hutter becomes Nina Harker.

A stage adaptation of Dracula written by Hamilton Deane and John Balderston opened in New York in 1927 with the Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi in the lead. It was around this time when Hollywood finally decided to compete with the Germans at making shadowy, menacing, Gothic horror films, but American hard-headedness still steered clear of the purely supernatural. In fact, a popular literary genre of the time specialised in bizarre mysteries which turned out to have a rational explanation, and that’s exactly what happened with London After Midnight (1927). This brought together two of Hollywood’s major talents – director Tod Browning and actor Lon Chaney – in a story concerning a vampire who, with his ghostly white-faced daughter, create terror throughout the English city. The whole affair turns out to have been a hoax by a police inspector anxious to trap a murderer. The film was remade by Browning during the sound era as Mark Of The Vampire (1935) with Bela Lugosi in the title role. But I digress.

A stage adaptation of Dracula written by Hamilton Deane and John Balderston opened in New York in 1927 with the Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi in the lead. It was around this time when Hollywood finally decided to compete with the Germans at making shadowy, menacing, Gothic horror films, but American hard-headedness still steered clear of the purely supernatural. In fact, a popular literary genre of the time specialised in bizarre mysteries which turned out to have a rational explanation, and that’s exactly what happened with London After Midnight (1927). This brought together two of Hollywood’s major talents – director Tod Browning and actor Lon Chaney – in a story concerning a vampire who, with his ghostly white-faced daughter, create terror throughout the English city. The whole affair turns out to have been a hoax by a police inspector anxious to trap a murderer. The film was remade by Browning during the sound era as Mark Of The Vampire (1935) with Bela Lugosi in the title role. But I digress.

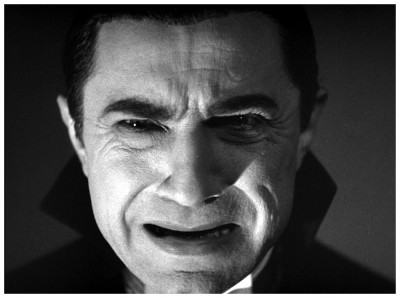

Three years following London After Midnight, Browning returned to the vampire theme with the most famous of all such films, Dracula (1931). As supposed classics go it’s a little feeble or, at any rate, it has not weathered well. Dracula was originally intended as a vehicle for Lon Chaney, who sadly passed away, so Universal turned to the relatively unknown Bela Lugosi, who was very familiar with the role following a three-year stint in the stage production. This opportunity for the Hungarian actor would not only change his life, but would forever associate Lugosi with Dracula (and later Ed Wood). Although no-where near as chilling as the silent Nosferatu: A Symphony Of Horror, which remains an unparalleled masterpiece, the 1931 version introduced the voice and the look that has become common practice. Lugosi’s performance is terribly hammy, and the torpid middle-European accent he gives Dracula must have surely seemed like self-parody, even back then.

Three years following London After Midnight, Browning returned to the vampire theme with the most famous of all such films, Dracula (1931). As supposed classics go it’s a little feeble or, at any rate, it has not weathered well. Dracula was originally intended as a vehicle for Lon Chaney, who sadly passed away, so Universal turned to the relatively unknown Bela Lugosi, who was very familiar with the role following a three-year stint in the stage production. This opportunity for the Hungarian actor would not only change his life, but would forever associate Lugosi with Dracula (and later Ed Wood). Although no-where near as chilling as the silent Nosferatu: A Symphony Of Horror, which remains an unparalleled masterpiece, the 1931 version introduced the voice and the look that has become common practice. Lugosi’s performance is terribly hammy, and the torpid middle-European accent he gives Dracula must have surely seemed like self-parody, even back then.

On the other hand, Dwight Frye is splendidly shrill and obsessive as Dracula’s lunatic disciple Renfield. The opening sequences in Dracula’s castle – where the unfortunate Renfield becomes the fly in the vampire’s web – have a good Gothic chill about them, with disturbingly sinister camerawork by the German cinematographer Karl Freund. As the eerie howl of a wolf echoes outside, Lugosi intones “Listen to them – children of the night – what music they make.” But the long London sequences that follow are merely stagey and dreadfully coy about the horrors, most of which occur discreetly off-screen, including the staking of Dracula through the heart.

On the other hand, Dwight Frye is splendidly shrill and obsessive as Dracula’s lunatic disciple Renfield. The opening sequences in Dracula’s castle – where the unfortunate Renfield becomes the fly in the vampire’s web – have a good Gothic chill about them, with disturbingly sinister camerawork by the German cinematographer Karl Freund. As the eerie howl of a wolf echoes outside, Lugosi intones “Listen to them – children of the night – what music they make.” But the long London sequences that follow are merely stagey and dreadfully coy about the horrors, most of which occur discreetly off-screen, including the staking of Dracula through the heart. Direct Hollywood sequels to Dracula include included Dracula’s Daughter (1936) with Gloria Holden as the eponymous lady, Son Of Dracula (1943) with Lon Chaney Junior as said son, and House Of Dracula (1945) with John Carradine. Later films include the British-made Dracula aka Horror Of Dracula (1958) and at least half-a-dozen sequels with Christopher Lee as the Count. Other notable productions include the made-for-TV movies Dracula (1973) with Jack Palance and Count Dracula (1977) with Louis Jordan, and the feature film Dracula (1979) with Frank Langella as a smoothly romantic version of the Count. In addition to all the forgoing, there have been scores of foreign-language films, ranging from a Hungarian Drakula (aka The Death Of Drakula 1921), to the Greek Dracula Tan Exarchia (1983). Nosferatu (1979) itself was remade in Germany with Klaus Kinski giving a notably ghoulish performance. 1992 saw a version produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola starring Gary Oldman. Despite mixed reviews, the film was a box-office hit and won three Academy Awards.

Direct Hollywood sequels to Dracula include included Dracula’s Daughter (1936) with Gloria Holden as the eponymous lady, Son Of Dracula (1943) with Lon Chaney Junior as said son, and House Of Dracula (1945) with John Carradine. Later films include the British-made Dracula aka Horror Of Dracula (1958) and at least half-a-dozen sequels with Christopher Lee as the Count. Other notable productions include the made-for-TV movies Dracula (1973) with Jack Palance and Count Dracula (1977) with Louis Jordan, and the feature film Dracula (1979) with Frank Langella as a smoothly romantic version of the Count. In addition to all the forgoing, there have been scores of foreign-language films, ranging from a Hungarian Drakula (aka The Death Of Drakula 1921), to the Greek Dracula Tan Exarchia (1983). Nosferatu (1979) itself was remade in Germany with Klaus Kinski giving a notably ghoulish performance. 1992 saw a version produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola starring Gary Oldman. Despite mixed reviews, the film was a box-office hit and won three Academy Awards.

But of all the sequels, prequels, remakes and reboots, there is one truly worthy of very special mention. The long-lost-but-rediscovered Spanish-language version of Dracula (1931), produced almost simultaneously with its American cousin, is not just a footnote or a sideshow to the Lugosi opus, but a solid contribution to the horror film genre and a movie that is at last available to all lovers of classic films. The genesis of Spanish Dracula begins around the time of changeover from silent to sound motion pictures. To satisfy the appetites of the millions of moviegoers in Europe, the Far East, Latin America and South America, Hollywood poured its product overseas and southward, unreeling millions of feet of film into theatres filled with people who spoke no English whatsoever. With the coming of sound, however, the foreign-language market which, in some cases, provided literally half the year’s revenue for some studios, seemed about to die a quick death, and dubbing was not yet technically viable as an alternative.

But of all the sequels, prequels, remakes and reboots, there is one truly worthy of very special mention. The long-lost-but-rediscovered Spanish-language version of Dracula (1931), produced almost simultaneously with its American cousin, is not just a footnote or a sideshow to the Lugosi opus, but a solid contribution to the horror film genre and a movie that is at last available to all lovers of classic films. The genesis of Spanish Dracula begins around the time of changeover from silent to sound motion pictures. To satisfy the appetites of the millions of moviegoers in Europe, the Far East, Latin America and South America, Hollywood poured its product overseas and southward, unreeling millions of feet of film into theatres filled with people who spoke no English whatsoever. With the coming of sound, however, the foreign-language market which, in some cases, provided literally half the year’s revenue for some studios, seemed about to die a quick death, and dubbing was not yet technically viable as an alternative.

For the most part, the Spanish-language Dracula is very well cast and performed. The actors from Spain in particular had excellent backgrounds in theatre and the performing arts. The role of Conde Dracula was given to a former native of Cordoba by the name of Carlos Villarias, who began his theatrical career in opera, later moving to the rapidly growing arena of motion pictures. He was, in fact, a very early member of the newly formed Spanish Film Studios. Villarias stood a good two metres tall with vaguely aquiline features and, from some angles, did resemble Bela Lugosi although, at thirty-eight, he was about a decade younger than the famed Hungarian. At its premiere in January of 1931, the Spanish-speaking audiences for Dracula were extremely receptive. The story, the performances, direction, and the overall mood of the picture won over its viewers completely. According to a trade magazine of the time, even Bela Lugosi was said to have proclaimed the film as “Beautiful!” The only problem with the film, as stated by the opening night crowd, was the mixture of accents: Argentinian, Spanish and Mexican dialects were used to represent the pseudo-Transylvanian Count and his pseudo-English hosts. Regardless of this cluttered international vocal mix, the movie proved itself more than satisfying to its first-run viewers.

For the most part, the Spanish-language Dracula is very well cast and performed. The actors from Spain in particular had excellent backgrounds in theatre and the performing arts. The role of Conde Dracula was given to a former native of Cordoba by the name of Carlos Villarias, who began his theatrical career in opera, later moving to the rapidly growing arena of motion pictures. He was, in fact, a very early member of the newly formed Spanish Film Studios. Villarias stood a good two metres tall with vaguely aquiline features and, from some angles, did resemble Bela Lugosi although, at thirty-eight, he was about a decade younger than the famed Hungarian. At its premiere in January of 1931, the Spanish-speaking audiences for Dracula were extremely receptive. The story, the performances, direction, and the overall mood of the picture won over its viewers completely. According to a trade magazine of the time, even Bela Lugosi was said to have proclaimed the film as “Beautiful!” The only problem with the film, as stated by the opening night crowd, was the mixture of accents: Argentinian, Spanish and Mexican dialects were used to represent the pseudo-Transylvanian Count and his pseudo-English hosts. Regardless of this cluttered international vocal mix, the movie proved itself more than satisfying to its first-run viewers.

The Spanish-language Dracula was essentially retired after its initial run to be placed in cinematic mothballs for almost fifty years, until it was finally screened again at the Museum Of Modern Art in the late seventies and, needless to say, to those who know the English-language version well, the conscious comparisons with the Tod Browning film were rampant throughout the screening. While many other foreign-language versions of Hollywood films no longer exist, the Spanish-language version of Dracula is an exception, and can be found as a bonus feature on the Classic Monster Collection DVD in 1999, the Legacy Collection DVD in 2004 and the 75th Anniversary Edition DVD set in 2006. In fact, you should go and get a copy right now! But not before you promise to return next week when I have the opportunity to freeze the blood in your veins with more sickening horror to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl in yet another fear-filled fang-fest for…Horror News! Toodles!

The Spanish-language Dracula was essentially retired after its initial run to be placed in cinematic mothballs for almost fifty years, until it was finally screened again at the Museum Of Modern Art in the late seventies and, needless to say, to those who know the English-language version well, the conscious comparisons with the Tod Browning film were rampant throughout the screening. While many other foreign-language versions of Hollywood films no longer exist, the Spanish-language version of Dracula is an exception, and can be found as a bonus feature on the Classic Monster Collection DVD in 1999, the Legacy Collection DVD in 2004 and the 75th Anniversary Edition DVD set in 2006. In fact, you should go and get a copy right now! But not before you promise to return next week when I have the opportunity to freeze the blood in your veins with more sickening horror to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl in yet another fear-filled fang-fest for…Horror News! Toodles!

Dracula (1931) is now available on Blu ray per Universal Studios on the

“Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection”

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Dracula. I remember when I was a kid , sitting home getting my vampire Halloween costume ready to go out and Trick or Treat, while watching Bela Lugosi in the 1931 version of Dracula on television. That was a moment in time. There were several, but that was one of them that molded me into the horror fan I am today.

It’s not really long lost though. It was available on VHS tape and it’s on the DVD Dracula Legacy collection which can still be found listed on amazon but it’s now out of print so you have to get it from a third party seller. It’s a nice box set so it may be worth it.