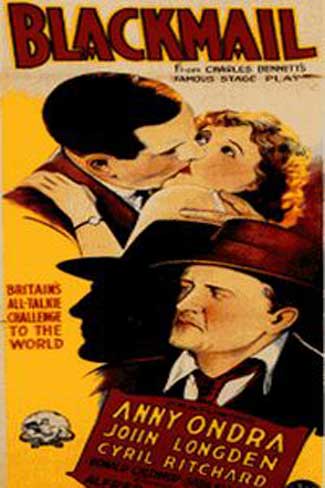

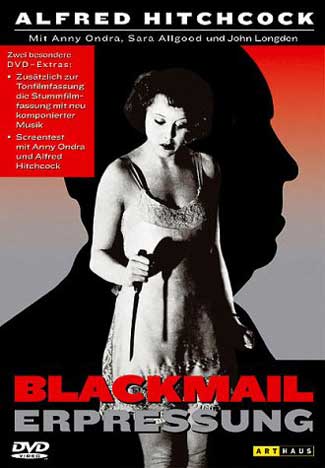

Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail marked the first time, in British cinematic history, that sound was used for an entire feature film. The infamous American musical The Jazz Singer (1927) has been cited as the first film to use dialogue; however, Al Jolson’s notorious film barely passes as a “talkie” as it incorporated only a “few” lines of dialogue. When considering the inability to adequately market a full-“talkie” at the time (only 20% of theatres could support a “talkie” picture) as well as some of the criticisms that dialogue would ruin the “visual art” that film had evolved into (one critic predicted it would turn the craft into hybrid monstrosities), Hitchcock had to shoot the entire film without the studio knowing he was utilizing the new technology to incorporate sound (Oh Alfred, you rebel! Viva la resistance de artistes!). In fact, the entire first reel was shot without sound and Hitchcock (ever the astute marketer…I mean, rebel) would release both a silent version and “talkie” version to audiences.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail marked the first time, in British cinematic history, that sound was used for an entire feature film. The infamous American musical The Jazz Singer (1927) has been cited as the first film to use dialogue; however, Al Jolson’s notorious film barely passes as a “talkie” as it incorporated only a “few” lines of dialogue. When considering the inability to adequately market a full-“talkie” at the time (only 20% of theatres could support a “talkie” picture) as well as some of the criticisms that dialogue would ruin the “visual art” that film had evolved into (one critic predicted it would turn the craft into hybrid monstrosities), Hitchcock had to shoot the entire film without the studio knowing he was utilizing the new technology to incorporate sound (Oh Alfred, you rebel! Viva la resistance de artistes!). In fact, the entire first reel was shot without sound and Hitchcock (ever the astute marketer…I mean, rebel) would release both a silent version and “talkie” version to audiences.

Hitchcock, being Hitchcock, made certain that his film would do more than just incorporate sound. Along with being the first British “talkie,” Blackmail could also, arguably, be considered the first woman revenge flick. The protagonist Alice is raped (we assume she’s being raped as the attack occurs behind a bed curtain after she’s stripped down to her undergarments, and one would assume by her screaming and flailing that she isn’t being tickled) by a high-cultured artist, Mr. Crewe (played by Cyril Ritchard – perhaps most famous for his role as Captain Hook in the 1954 musical adaptation of Peter Pan).

Midway through the rape, Alice grabs for a knife lying on a bedside table. She brandishes the knife (which looks a lot like the knife Norman Bates uses in Psycho) and then, assumedly, plunges it into Mr. Crewe. What ensues is a crazy-ass Freudian world of turmoil…

What is interesting to me about Blackmail isn’t the fact that it is the first British “talkie,” nor that it is arguably the first woman-revenge film. Instead, what’s fascinating about the film is Hitchcock’s onscreen fascination with…well…c**ks. And perhaps more importantly, how these visual phallic symbols serve as commentary on Alice’s struggle to assert herself in this strange coming-of-age tale.

The film opens with a seemingly open and shut case that has apparently nothing to do with the crux of the film’s plot. Cops show up at a criminal’s apartment. Criminal is reading a paper while sitting on his bed. Criminal jumps for weapon. Cops subdue criminal. Criminal is booked. No dialogue is used as really there is no need for it.

It is right after this scene where things get interesting. We meet Alice as she waits for her boyfriend to get out of work. “Work” is the police station as her boyfriend is Detective Frank Webber (played by actor John Longden). Frank gets out of work late and shares a laugh with one of his buddies in blue. Clearly annoyed with Frank, we see our first instance of blackmail as Alice plays the all-too-familiar domestic relationship game of the silent treatment. After apologetic advancements by Frank, Alice finally relents. However, friction sprouts up again at dinner when Frank says he wants to go see a movie called Fingerprints and Alice does not (all the while during dinner, Alice is making eyes with Mr. Crewe).

Alice, again, plays a game with Frank telling him she doesn’t want to see the movie, he basically says screw you and stomps off to check out his film…and of course, Mr. Crewe slides right into Frank’s spot once the d*ck, er, detective leaves the dining hall.

As stated earlier, the symbolism within the plot really becomes interesting right after Crewe attempts to rape Alice and she, in turn, stabs him to death with the blatantly phallic knife…because how else can a woman defend herself against a penis other than to use another penis? This is where the penises pop up faster than free beer night at your local titty bar. While running through an empty square in which all that stands in the shot (aside from Alice) is a massive erect monument – quite possibly memorializing the accomplishments of penises, er, men in combat. Alice pauses for a moment to gaze upon a neon sign flashing “Good Cocktail” in which a c**ktail shaker flashes and shakes, but from her POV we see her visualizing the c**ktail shaker as a knife in a masturbatory stabbing motion. She flees, as any of us would, from the flashing c**ktail.

After being chased by images of penises, Alice finally gets to her family’s home which is an apartment attached to her father’s store: a cigar shop. (But of course! What else would the patriarch within the story own?) As Alice sits at the breakfast table clearly shaken, not stirred, by the trauma that has just unfolded, she falls into the traumatic reliving of the scene as all she can hear the people around her utter is the word: knife…knife…knife…knife…knife. (Though perhaps when you watch it for yourself, you’ll giggle as wildly as I did thinking: penis…penis…penis.)

If the establishment of the fact that Alice is living in a man’s world is not made clear by this point, both Frank and a stranger show up at the store. Frank had been among the first to arrive at the scene of the crime where he found Alice’s, ahem, glove. The stranger shows up with in his possession the other glove that Alice had dropped outside of Crewe’s building. This stranger’s intention is obvious: honest, straightforward blackmail. He shows the glove to Frank and Alice (who begins to tremble and freak out), then asks the oblivious dad for the best possible c**k, er, cigar that the store carries. With the negotiating power sitting in his corner, the stranger happily puffs away on his massive cigar. When the stranger is finished, Frank lights up his tiny cigarette and begins to smoke nervously…that is, until he receives a call from the station and recognizes that he can peg the murder on the stranger as Crewe’s landlady has mentioned seeing the stranger outside the building. When Frank returns from the phone call, he whips out another cigarette and this time confidently puffs away.

All the meanwhile, Alice is a trainwreck of a human psyche. First, we assume she’s hysterical because she fears of telling Frank the whole truth of the incident. Before she can say anything, he pulls out the glove…and now can she really tell him the truth? What would she say? “Frank, I love you…but after you left, I went to a stranger’s apartment, stripped down to my skivvies for him…and when I told him no, I had no choice but to repeatedly stab him.” It’s 1929, would a guy like Frank understand?

Then, we assume Alice is nervous as hell when the stranger shows up and presents the other glove. Murder means the death penalty. She’s screwed. That is, until Frank realizes he can peg this entire thing on the stranger who soon becomes mortified of what this d*cktective can, and is planning to, do. But Alice doesn’t seem okay with that either. Her conscience can’t live with that and she attempts to confess to what really happened, but Frank keeps telling her to shut her trap so he can handle it in the manly-man way he plans to handle it.

When the other cops show up, the stranger takes flight. Frank and his crew chase after the stranger to a museum where now the final showdown will take place. And of course, what better imagery than to be certain to include in the opening shots of the chase scene of the museum, a half dozen massive erect columns dwarfing the stranger and his would-be captors. It’s a wonderful sequence that ultimately ends with the stranger reaching the top of the building only to fall through a glass dome shaped like…nope, not a penis…a massive breast!

Damn fatal women.

In the meantime, Alice has made up her mind. She is going to go down to the station and confess while Frank is busy chasing down the stranger. She sits at a table, picks up a penis, sh*t, I mean pen, and writes a letter to Frank – because in a man’s world, how else can she communicate other than with a pen? She finishes the letter, stands up (culminating a separate beautiful visual incorporating shadows that you must check out), and marches down to the station where she demands she offers information on who the killer of Mr. Crewe is.

However, moments before she is about to confess, Frank shows up. The tables have turned. With the stranger dead, she can get away scot-free and Frank takes her out of the station holding her hand. A new blackmail has occurred in that Frank now holds the negotiating power in the relationship. As they leave the station, Frank makes a joke with his buddy and they laugh it up heartily, while Alice’s face is one of hysteria and insanity.

In a matter of an hour and a half, Hitchcock’s Blackmail offers an explanation behind the hysterical nature of women. They’re trapped in a world dominated and run by men. Crimes are black and white, and if they aren’t black and white, then damn it, we’ll water down so that it is easily digestible. Women’s voices are suppressed by the legal and social structures men surround them with…but eh, f*ck it, you can always indulge yourself a vice or two…like say a cigar…or a c**ktail.

Belton, John. “Awkward Transitions: Hitchcock’s ‘Blackmail’ and the Dynamics of Early Film Sound.” The Musical Quarterly 83 (Summer 1999): 227-246.

Belton’s article is a tremendously informative, though slightly technical (jargony), article.

The protagonist Alice White (“white” for purity? yes, white for purity) was played by silent film actress Anny Ondra – who, ironically, would have her acting career shortened because of the inclusion of sound in film due to her thick eastern European accent that was considered too difficult to comprehend…Hitch had to hire actress Joan Barry to dub Ondra’s lines. So far as Ritchard, Wikipedia claims that Captain Hook is his most famous role. (Personally, I like his Mr. Crewe better.)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews