A common theme among the iconic science-fiction author Phillip K. Dick focused on a simple question, “What does it mean to be human?” In his short stories and extended works such as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (aka Blade Runner), Dick examined humanity through inhuman characters such as androids and aliens. Other creative talents explored similar questions in scores of artistic mediums.

In 1970, writer Len Wein and artist Bernie Wrightson indirectly examined the question and its themes when they created the character of Alec Olsen; a man turned into a swamp creature in a short story for the D.C. Comics’ anthology House of Secrets. The story proved popular enough to launch a spin-off series focusing on Alec Holland; a man turned into the moss creature known as the Swamp Thing.

Other authors took over creative duties in Swamp Thing comics long after the original early 1970s first volume concluded. Still, the aura of Wein/Wrightson’s seminal work carried over, to one degree or another, in other writers and artists’ interpretations. We even see the initial creator’s themes in the new, and short-lived, Swamp Thing streaming series.

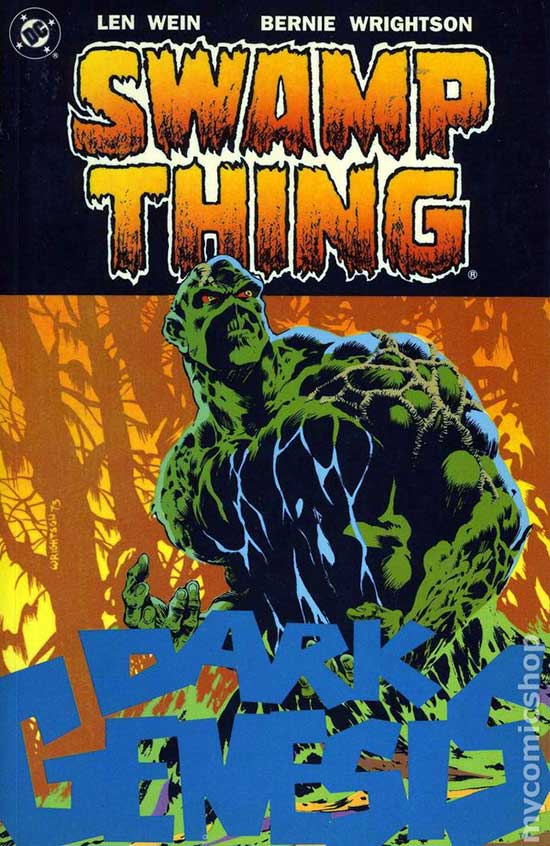

The trade paperback Swamp Thing: Dark Genesis presents the original House of Secrets short story along with the first ten issues from Swamp Thing Volume One. These early stories provide a compelling mix of horror and superheroism that likely influenced Marvel Comics’ horror line of the early 1970s. Re-reading the TPB after 25 years offers a chance to explore themes examining, “What does it mean to be human?” present in the tales. Three issues, in particular, draw attention to the complex theme.

“The Patchwork Man” – Swamp Thing Vol 1, Issue 3

The influences of the issue’s debuting character aren’t challenging to figure out. Since early Swamp Thing issues drew inspiration from classic horror, the “Patchwork Man” character bears far more than a mild resemblance to the Frankenstein Monster. Elements of the story, such as angry villagers, serve as homages to the Universal horror films. The series’ themes of tortured humanity blend well with similar themes from the Frankenstein mystique while allowing the story to stand on its merits and not come off as purely derivative.

Altered physically after lab experiments and referred to in passing as the “Patchwork Man,” the goodhearted central character is named real name is Gregori Arcane. Gregori tries, at first, to help and befriend the Swamp Thing. The Swamp Thing welcomes Gregori’s assistance, as he doesn’t realize Gregori is the brother of his nemesis, Anton Arcane. The reader also learns Gregori, the father of future Swamp Thing paramour Abigail Arcane. Unable to speak, Gregori cannot tell Abigail he is her father. Nor can he articulate why he becomes so protective of her.

An eventual confrontation with human characters, however, upends any chance Gregori has at a peaceful existence.

If there were a consistent conflict experienced by several so-called monsters, it would be how people misunderstand them. Cruel judgments often derive from repulsion. Scarred or otherwise misshapen, monsters disgust people who only see their exterior appearance. No surprise Wein and Wrightson chose to feature a Frankenstein-like creature. Mary Shelley’s original work saw the tortured monster deal with the same judgments.

The fear born of harsh, unfair judgments about a being’s physical form, creates a violent reaction. The humans tend to act quite inhumanely towards tragic creatures who do nothing to deserve their fate nor their treatment. No matter. The villagers eventually descend upon the outcasts and act more monstrous than the monsters.

Why is there any misunderstanding? Neither Swamp Thing nor Gregori does anything overtly violent to the villagers. Gregori does attack Swamp Thing when he believes Holland intends to hurt Abigail. And neither Swamp Thing nor Gregori displays anything threatening towards Abigail, but their garish forms combined with a proximity to the girl is enough. The villagers then rage.

Gregori Arcane, the Patchwork Man, like Alec Holland, the Swamp Thing, finds too many human-imposed barriers to set things straight. Although more human than most of their human cast of characters from an empathy perspective, the monsters suffer. Fair or not and cruel as it may be, that is the way things are.

“Monster on the Moors” – Swamp Thing Vol 1, Issue 4

Swamp Thing further embraced the traditional horror genre in its fourth issue. With this outing, the title’s tragic antihero confronts a werewolf.

Picking up after the events of the previous issue, Swamp Thing and his supporting cast find themselves suffering after a plane crashes in the Scottish moors. The opening page’s descriptive prose makes references to the wreckage that was once a seaplane and compared it to the “twisted ruin of work once had been a man. “The cruel description unfairly laments Swamp Thing’s lack of humanity. The Swamp Thing certainly does not lack either human compassion or empathy. The same cannot be said of the antagonists he faces in the story. The werewolf takes human form most times, and the full moon brings forth his desire to commit animalistic stalking and murder.

Still, is the werewolf a tragic creature like the Swamp Thing? The reader may somewhat understand the creature’s curse and plight, but, unlike, Swamp Thing, the werewolf does not garner sympathy. Why isn’t he taking steps to curtail his murderous rampages in some way? Perhaps any sympathy directed towards the werewolf comes from a predisposed response derived from watching Lon Chaney Jr. films. This issue’s were-monster does at least become self-actualized to the fact he bears some responsibility for his werewolf form’s actions. At that point, the monster becomes somewhat humanized and garners sympathy.

Utterly unsympathetic, however, is the werewolf’s matriarch. We learn the werewolf’s mother has long lured planes to crash on the moors to trap the survivors. Anyone unlucky enough to survive becomes targeted for a blood transfusion to transfer the curse of the werewolf from her son to someone else. In a moment of clarity at the story’s conclusion, the werewolf son understands the cruelty and selfishness of the plan, and he won’t go along with his mother’s intentions.

The brutal irony here is the least human of the three characters is the werewolf’s mother. The Swamp Thing never lost his humanity, the wolf monster, however, only loses its humanity transitionally when the moon rises, but the werewolf’s mother never possessed any level of kindness or compassion. Being human is often described by how you act and treat others. Your mother character sociopathically serves only herself and her son.

The human lacks humanity. The half-man/half-wolf possesses some humanity. And the supposed monster, the Swamp Thing, is the most human of all.

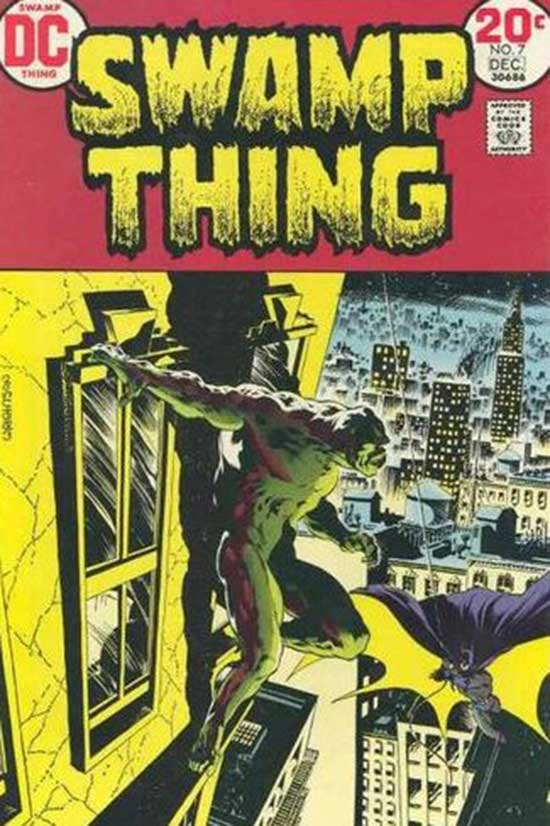

“Night of the Bat” – Swamp Thing Vol 1, Issue 7

Could anything do more harm to a cynic’s belief in humanity than seeing an iconic character fail prey to blind prejudice? Batman swings into action in issue 7, likely a marketing ploy to help draw some new readers to the title, comic book fans unfamiliar with the (then) new swamp creature hero. Batman, unlike many already-established regular readers of Swamp Thing, doesn’t know who the moss-covered Alex Holland is. And hardcore Swamp Thing readers were probably appalled at Batman’s treatment of the former Alec Holland.

The vaunted “great detective” appears disinterested in performing even rudimentary detective work. Batman reacts violently to Swamp Thing the minute they cross paths. The hero’s reactions reflect a banal refusal even to entertain the notion the moss creature has a shed of humanity.

In the issue, Swamp Thing turns up in Batman’s territory to search for Abigail Arcane and Matt Cable. A syndicate organization kidnapped both. The moss monster knows he’ll draw unwanted attention in the big city, so he plans on wearing a disguise. Not surprisingly, Swamp Thing’s decision to wear a make-due hat and trench coat costume does little good. The police quickly pick up on a “monster” running loose in Gotham City, especially one who makes a ruckus when breaking a storefront window to steal clothes. Even swamp monsters with their own comic book series suffer judgment lapses at times.

Commissioner Gordon worries, understandably, after hearing the news about the creature’s confrontation with the police. After using the bat signal to summon the Dark Knight, Gordon asks Batman to unravel the mystery behind the monster. Regular readers know Swamp Thing ventured to the famous city to find his lost companions Abigail Arcane and Matt Cable. Batman does not and assumes the worst about the swamp man.

After a short search, Batman confronts the Swamp Thing and immediately makes a judgment call based on the creature’s appearance. The detective ignores the massively powerful monster’s refusal to fight back. Unfortunately, Swamp Thing cannot verbally articulate its desire not to fight, but a superhero such as Batman should have figured out the creature means no harm. Swamp Thing even repeatedly backs off, passive behavior that backfires and makes Batman more aggressive.

Why is the hero so intent on fighting? And doesn’t Batman see that Swamp Thing has a pet dog with him?

The Dark Knight never realizes the presence of the Swamp Thing’s canine sidekick should disqualify the moss monster from any villainy. Swamp thing travels to Gotham city accompanied by his faithful dog named Mutt. Since when do evil villains intent on causing mayhem bring along their loyal and friendly four-legged canine companions? The glaring clue does not affect the Cape Crusader’s mindset. Batman won’t look beyond Swamp Thing’s appearance, And never acknowledges how Mutt sheds light on the caring, human side of the supposed monster.

You would think the all-too-human Batman would pick up on the Swamp Thing’s humanity.

“Batman” is merely a costume and a pseudonym, as the man under the cape and cowl is Bruce Wayne. “Batman” doesn’t genuinely exist, and, at this point in the character’s history, neither does “Swamp Thing.” Alec Holland and Swamp Thing are the same.* Holland, however, cannot shed moss form. Batman can remove his costume. In costume, during this story, Batman blindly removes his compassion, empathy, and humanity. Ironically, Swamp Thing retains his.

Batman concludes the issue by saying, “I’m betting there’s a lot more to [The Swamp Thing] as well…Maybe someday I’ll take the time to find out what it is.” Is there a reason why Batman couldn’t do this from the beginning besides willful, prejudiced blindness?

All Too Human in an Inhuman World

The turbulent life and times of the Swamp Thing played out over several decades of comic book publishing narratives. Swamp Thing issue #1 detailed the deliberate act of sabotage that forever changed Alec Holland’s appearance. In the subsequent issues of volume one, Holland/Swamp Thing never lost his humanity. Others weren’t as charmed.

—

*Swamp Thing’s origin and “true” identity changed dramatically in the 1980s with Alan Moore’s brilliant “Anatomy Lesson” story arc.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews