SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

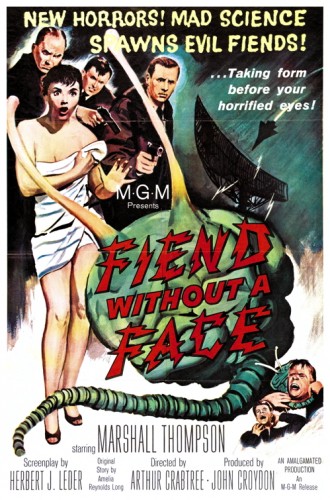

“An American military base in Canada is developing a missile control system based on nuclear energy and is facing problems with the people from the nearby town. When four locals including the Mayor are killed, Major Jeff Cummings (Marshall Thompson) is put in charge of the investigation. When the coroner examines the one of the corpses, he finds that the brain and spinal chord were sucked out and Major Cummings defines the creature as a mental vampire. He looks for Professor R.E. Walgate (Kynaston Reeves), a retired scientist that lives in town, and he discloses the scary secret.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

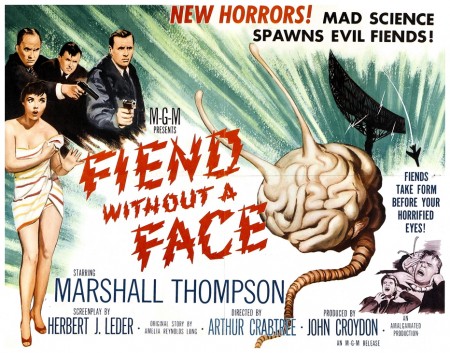

During the mid-fifties in America, the actions of irresponsible scientists were continuing to create monsters, often based on various members of the family of Arthropoda. A more imaginative and lower-budget form of monster emerged in Fiend Without A Face (1958) in the shape of small creatures that look like human brains, hop wildly about and attach themselves to people’s spinal columns by drilling holes in their necks, through which they suck out the nervous tissue. Amalgamated Films was a British studio that produced two science fiction movies in the late fifties, both of which were set in North America, both starring Hollywood actor Marshall Thompson. One was First Man Into Space (1959), in which an astronaut returns to Earth covered in ‘meteor shit’ with a thirst for blood, a major inspiration behind The Incredible Melting Man (1977).

A different team were responsible for the other Amalgamated production, Fiend Without A Face, which is a far more interesting film. Directed by former cinematographer Arthur Crabtree, it was written by Herbert J. Leder based on a 1930 short story published in Weird Tales magazine entitled The Thought Monster by Amelia Reynolds Long. As a matter of fact, my old friend Forrest J. Ackerman brokered the sale of her story to the film’s producers. Screenwriter Leder was actually signed to direct, but was unable to obtain a British permit in time, so Crabtree was called in at the last minute. Crabtree had absolutely no interest in the subject matter, declaring that science fiction was beneath him, and often didn’t show up for work. Eventually Crabtree walked off the picture altogether, and lead actor Thompson ended up directing the film himself.

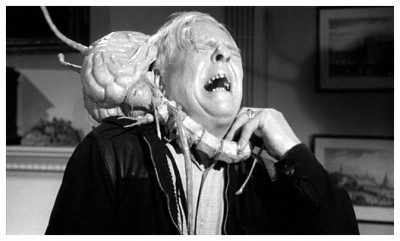

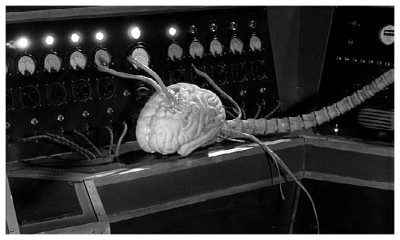

The story involves a scientist whose experiments with a machine that can amplify thought-waves accidentally bring into being creatures which consist of pure energy. Invisible at first, they commit a series of murders by sucking out their victims’ brains through holes punctured in the base of the necks. In the final sequences, when the creatures have trapped the protagonists in a remote house, they gradually take form, revealing themselves to be disembodied brains trailing writhing spinal cords and twitching tendrils. It is when they materialise that the film really comes to life, giving the lie to the theory that it is always better to suggest than merely to show. The climax, in which the brains smash their way into the house and attack the occupants, has a genuine nightmarish quality and the special effects, featuring some clever stop-motion photography, an unusual practice for such a low-budget science fiction thriller of this era.

The story involves a scientist whose experiments with a machine that can amplify thought-waves accidentally bring into being creatures which consist of pure energy. Invisible at first, they commit a series of murders by sucking out their victims’ brains through holes punctured in the base of the necks. In the final sequences, when the creatures have trapped the protagonists in a remote house, they gradually take form, revealing themselves to be disembodied brains trailing writhing spinal cords and twitching tendrils. It is when they materialise that the film really comes to life, giving the lie to the theory that it is always better to suggest than merely to show. The climax, in which the brains smash their way into the house and attack the occupants, has a genuine nightmarish quality and the special effects, featuring some clever stop-motion photography, an unusual practice for such a low-budget science fiction thriller of this era.

The director of the effects sequences was Florenz Von Nordoff, while Peter Neilson headed up the British practical effects’ crew. The stop-motion animation was actually done in Munich by German effects artist K. L. Lupel. There can be no purer surrealism in cinema than the sight of these twitching brain-things besieging a house full of people, leaping and plopping like possessed frogs. The entire climax has the bizarreness of some mad medieval allegory, like a triptych by Hieronymus Bosch. The film created a public uproar after its premiere at the Ritz Theatre in Leicester Square. The British Board of Film Censors had already demanded a number of cuts before granting it the ‘X’ certificate, but newspaper critics were still aghast at its horrifying special effects. Questions were actually raised in Parliament as to why British censors had allowed the film to be released and further asked what was the British film industry thinking in trying to beat Hollywood at its own game of overdosing on blood and gore.

The director of the effects sequences was Florenz Von Nordoff, while Peter Neilson headed up the British practical effects’ crew. The stop-motion animation was actually done in Munich by German effects artist K. L. Lupel. There can be no purer surrealism in cinema than the sight of these twitching brain-things besieging a house full of people, leaping and plopping like possessed frogs. The entire climax has the bizarreness of some mad medieval allegory, like a triptych by Hieronymus Bosch. The film created a public uproar after its premiere at the Ritz Theatre in Leicester Square. The British Board of Film Censors had already demanded a number of cuts before granting it the ‘X’ certificate, but newspaper critics were still aghast at its horrifying special effects. Questions were actually raised in Parliament as to why British censors had allowed the film to be released and further asked what was the British film industry thinking in trying to beat Hollywood at its own game of overdosing on blood and gore.

The ultimate in anti-intellectual films (there aren’t too many movies in which the villains are carnivorous brains), it has understandably developed a cult following. Sometimes the film industry is like a symbol of the Freudian model of the human mind. The industry’s super-ego sees to it that its big-budget productions are respectable but, hidden behind the walls and down in the basement lurks the industry’s Id, the concealed subconscious, which every now and then explodes into action and throws up images so bizarre as to call into question the rationality of human existence. The continued vitality of genre cinema has been largely due to these strange disreputable leaks from areas of the industry that people would sooner not know about, and Fiend Without A Face is a particularly crazed example.

The ultimate in anti-intellectual films (there aren’t too many movies in which the villains are carnivorous brains), it has understandably developed a cult following. Sometimes the film industry is like a symbol of the Freudian model of the human mind. The industry’s super-ego sees to it that its big-budget productions are respectable but, hidden behind the walls and down in the basement lurks the industry’s Id, the concealed subconscious, which every now and then explodes into action and throws up images so bizarre as to call into question the rationality of human existence. The continued vitality of genre cinema has been largely due to these strange disreputable leaks from areas of the industry that people would sooner not know about, and Fiend Without A Face is a particularly crazed example.

By 1958 the monster-movie boom was beginning to run out of steam, and smaller companies were taking over from the major studios in this area, like my old friend Roger Corman‘s Attack Of The Crab Monsters (1957) and The Wasp Woman (1959). Other recommended creature-features of the era include Twenty Million Miles To Earth (1957), The Mysterians (1957), The Most Dangerous Man Alive (1958), Caltiki The Immortal Monster (1959), Gorgo (1959) and The Tingler (1959). Temporarily submerged, the monster movie was by no means dead, and it soon returned triumphantly with a lavish production from a major studio: Alfred Hitchcock‘s The Birds (1963), but that’s another story for another time. Please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the Public Domain for…Horror News! Toodles!

Fiend Without A Face (1958)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews