SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

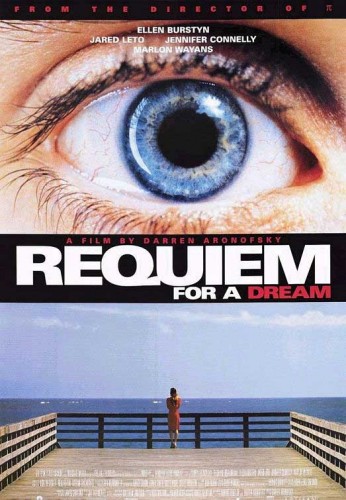

“Pills and heroin offer fulfillment of the dreams of four residents of Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach in the shadow of a crumbling Coney Island amusement park. Sarah dreams of appearing on television wearing a red dress that’s a bit snug. So she starts a diet assisted by uppers. Her son Harry, his girlfriend Marion, and his best friend Tyrone pin their hopes for money on moving up from pushing nickel bags of heroin to buying in bulk. They also deal to support their growing habits. Things are going well: Harry buys his mom a new television, she’s losing weight, she has status among her friends, Tyrone’s girlfriend is cool, and the team has money in a shoe box. These dreams are addictive.”

REVIEW:

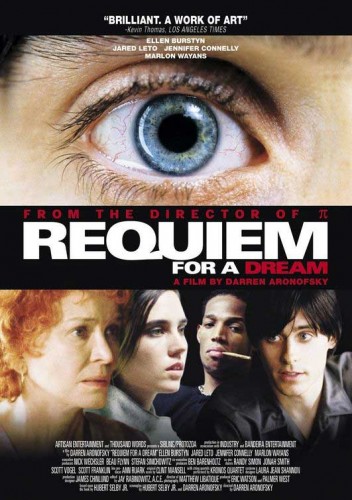

On the strength of his film Requiem For A Dream (2000), Darren Aronofsky was approached to direct Batman Begins (2005), fulfilling what must be a dream shared by most young filmmakers as they struggle to put together their first movie. But, as it turned out, Aronofsky was an unlikely candidate for mainstream Hollywood. His acclaimed US$60,000 debut feature, Pi (1998), was a deliriously trippy black-and-white exploitation of paranoia packed with disturbing imagery and sounds. His follow-up, the US$4.5 million Requiem For A Dream is even wilder – and in colour!

Based on the novel by Hubert Selby Junior, the creator of Last Exit To Brooklyn (1989), Requiem For A Dream immerses us in the cracked psyches of a group of friends, lovers and relatives divided by their various addictions, whether it be drugs, television, chocolate, dieting, or popular culture. Hard-hitting and confrontational, it is obviously Aranofsky’s attempt to cinematically capture the impact felt when one first reads the book. Requiem For A Dream was never going to be an easy text to turn into popcorn fodder. What is essentially the tale of four people’s descent into drug hell could be deemed a tad glum for the average boobs-and-bombs film-goer. It’s true, this is depressing stuff. This is traumatic. This is the cinematic equivalent of having root canal surgery. And yes, it also comes pretty damn close to being a masterpiece.

Based on the novel by Hubert Selby Junior, the creator of Last Exit To Brooklyn (1989), Requiem For A Dream immerses us in the cracked psyches of a group of friends, lovers and relatives divided by their various addictions, whether it be drugs, television, chocolate, dieting, or popular culture. Hard-hitting and confrontational, it is obviously Aranofsky’s attempt to cinematically capture the impact felt when one first reads the book. Requiem For A Dream was never going to be an easy text to turn into popcorn fodder. What is essentially the tale of four people’s descent into drug hell could be deemed a tad glum for the average boobs-and-bombs film-goer. It’s true, this is depressing stuff. This is traumatic. This is the cinematic equivalent of having root canal surgery. And yes, it also comes pretty damn close to being a masterpiece.

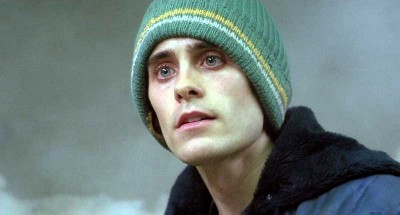

Who ever said a drugs movie should be fun? The characters in Trainspotting (1996) had it easy compared to the quartet in this. Ellen Burstyn plays Sarah Goldfarb, an aging Brooklyn widow who worries about her wayward son Harry (Jared Leto) and looks to her television for company. When she’s approached to apply to be a game show contestant her life begins to unravel even further. Fueled by her desire to look good for the camera, she starts dieting, aided by a dodgy back-street quack with a profitable sideline in pushing appetite suppressants. Within a few months she’s hooked – uppers for lunch, downers for dinner, food is the devil and the fridge is its lair. In fact, this is the most demonic fridge since Ghostbusters (1984) as it shuffles ominously after Sarah.

Who ever said a drugs movie should be fun? The characters in Trainspotting (1996) had it easy compared to the quartet in this. Ellen Burstyn plays Sarah Goldfarb, an aging Brooklyn widow who worries about her wayward son Harry (Jared Leto) and looks to her television for company. When she’s approached to apply to be a game show contestant her life begins to unravel even further. Fueled by her desire to look good for the camera, she starts dieting, aided by a dodgy back-street quack with a profitable sideline in pushing appetite suppressants. Within a few months she’s hooked – uppers for lunch, downers for dinner, food is the devil and the fridge is its lair. In fact, this is the most demonic fridge since Ghostbusters (1984) as it shuffles ominously after Sarah.

Harry quickly recognises his mother’s predicament, not least because he’s a heroine fiend himself. He lives a precarious existence with his drug cohorts, his girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly) and Tyrone (Marlon Wayans). They’re more clued-in to the perils of addiction than Sarah but, sadly, no better at escaping its grip. From Spring to the following Winter, the four follow a predictable desperate path: Scoring, stealing and self-delusion – four seasons in one hell. As Sarah loses her mind, Harry quite literally rots his body and Marion slips into prostitution, providing few redemptive outlets for the viewer. This is deliberate, as is the fact that the colour red is only really seen in Sarah’s hair and red dress.

Aronofsky’s skill is finding the bruised humanity among the squalor using a dazzling array of visual styles creating the claustrophobic fishbowl world of addiction. While it owes a debt to Gus Van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy (1989) and a nod to David Lynch, Aranofsky’s vision has managed to stake out his own territory. It may be uncomfortable but it’s also extraordinarily affecting and unique. Sharing experiences, whether they be good or bad, is what Aranofsky’s film-making is all about. It’s not the alienation of characters like the paranoid mathematician in Pi, or the pill-popping mother in Requiem For A Dream that fascinates him, but the opportunity it offers to go into someone’s mind.

Some critics have complained that the characters in Requiem For A Dream are merely puppets, and that Aronofsky has only chosen the material for the opportunities it offers him to experiment with his film-making. Nevertheless, there seems to be a discrepancy between the man and his material. Generally clean-cut and self-assured, it’s hard to believe this forty-year-old Harvard Alumnus has had first-hand experience with almost everything portrayed in both Pi and Requiem For A Dream. So why focus so intently on the dark side of the human condition?

“I just think there are more unhappy people on the planet than there are happy people. To feel good about yourself and feel good about your world, you have to go through a lot of darkness. Just look at the planet; It’s a pretty f*cking f*cked up place.” (Darren Aronofsky, December 2001). Keep that thought in mind for the next seven days, gentle reader, and join me again next week so I can poke you in the mind’s eye with another pointed stick from the faggot formerly known as Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

“I just think there are more unhappy people on the planet than there are happy people. To feel good about yourself and feel good about your world, you have to go through a lot of darkness. Just look at the planet; It’s a pretty f*cking f*cked up place.” (Darren Aronofsky, December 2001). Keep that thought in mind for the next seven days, gentle reader, and join me again next week so I can poke you in the mind’s eye with another pointed stick from the faggot formerly known as Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews