SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“England is torn in civil strife as the Royalists battle the Parliamentary Party for control. This conflict distracts people from rational thought and allows unscrupulous men to gain local power by exploiting village superstitions. One of these men is Matthew Hopkins, who tours the land offering his services as a persecutor of witches. Aided by his sadistic accomplice John Stearne, he travels from city to city and wrenches confessions from ‘witches’ in order to line his pockets and gain sexual favors. When Hopkins persecutes a priest, he incurs the wrath of Richard Marshall, who is engaged to the priest’s niece. Risking treason by leaving his military duties, Marshall relentlessly pursues the evil Hopkins and his minion Stearne.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

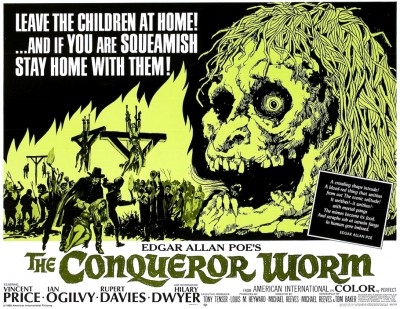

While 1968 was chiefly notable for its great advances in cinematic science fiction, the genre of supernatural horror was also undergoing radical changes. One of the most important milestones in this area was a film that was released comparatively quietly: The Conqueror Worm (1968), known in some countries as Witchfinder General. The paradox is that this low-budget production was not strictly speaking a fantastic film at all, since there is no evidence that the witches (whose dreadful persecution is the film’s subject matter) had any real supernatural powers.

Produced by the British Tigon organisation, the film keenly exploited the commercially successful costume horrors from Hammer in the UK and Roger Corman in the US. Nevertheless the film has a broodingly sinister atmosphere, with Vincent Price playing the historical figure Matthew Hopkins, who traveled the country executing supposed witches under the powers given to him by the Roundhead parliament during the Civil War.

Produced by the British Tigon organisation, the film keenly exploited the commercially successful costume horrors from Hammer in the UK and Roger Corman in the US. Nevertheless the film has a broodingly sinister atmosphere, with Vincent Price playing the historical figure Matthew Hopkins, who traveled the country executing supposed witches under the powers given to him by the Roundhead parliament during the Civil War.

The Conqueror Worm is one of the few films directed by Michael Reeves in his awfully brief career. As a child he started making short films featuring his school friend Ian Ogilvy. His first professional work was as an associate director on The Long Ships (1964), and then as second-unit director on Castle Of The Living Dead (1964), taking over as director mid-production. When he got The She-Beast (1966) right to everyone’s amazement, he was entrusted with bigger budgets and made better films. In 1967 he directed and co-wrote The Sorcerers (1967), giving Boris Karloff a major role in one of the few films worthy of his talent.

The Conqueror Worm is one of the few films directed by Michael Reeves in his awfully brief career. As a child he started making short films featuring his school friend Ian Ogilvy. His first professional work was as an associate director on The Long Ships (1964), and then as second-unit director on Castle Of The Living Dead (1964), taking over as director mid-production. When he got The She-Beast (1966) right to everyone’s amazement, he was entrusted with bigger budgets and made better films. In 1967 he directed and co-wrote The Sorcerers (1967), giving Boris Karloff a major role in one of the few films worthy of his talent.

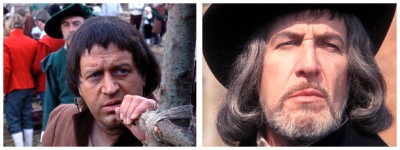

Reeves even refused to allow my old friend Vincent Price to overact in The Conqueror Worm. Annoyed, Vincent snapped “Young man, I have made eighty-four films. What have you done?”, to which Reeves replied “I’ve made two good films.” All was forgiven when Vincent saw the end product. Alas, on the 11th of February 1969, whilst working on The Oblong Box (1969), Michael Reeves passed away aged just twenty-five, when he unwittingly combined alcohol and sleeping pills. We lost a major talent and many fine films, and The Oblong Box became part of Gordon Hessler’s unimpressive career.

Reeves even refused to allow my old friend Vincent Price to overact in The Conqueror Worm. Annoyed, Vincent snapped “Young man, I have made eighty-four films. What have you done?”, to which Reeves replied “I’ve made two good films.” All was forgiven when Vincent saw the end product. Alas, on the 11th of February 1969, whilst working on The Oblong Box (1969), Michael Reeves passed away aged just twenty-five, when he unwittingly combined alcohol and sleeping pills. We lost a major talent and many fine films, and The Oblong Box became part of Gordon Hessler’s unimpressive career.

Michael Reeves gave his boyhood friend Ian Ogilvy major roles in three of his films, and he gave a good performance each time. Ogilvy subsequently appeared in many television shows in England and America. My personal favourite is his portrayal of Grayson, the school bully in the Ripping Yarns episode Tompkinson’s School Days. In 1978 he played Simon Templar in all twenty-four episodes of The Return Of The Saint, though being regarded as the new Roger Moore was hardly a step in the right direction. With no mate to give him continued employment, Mr. Ogilvy occupied his spare time by writing children’s books. They don’t know too many words, how hard can it be? His last prominent role was as hairdresser to the stars Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn in Death Becomes Her (1992).

Michael Reeves gave his boyhood friend Ian Ogilvy major roles in three of his films, and he gave a good performance each time. Ogilvy subsequently appeared in many television shows in England and America. My personal favourite is his portrayal of Grayson, the school bully in the Ripping Yarns episode Tompkinson’s School Days. In 1978 he played Simon Templar in all twenty-four episodes of The Return Of The Saint, though being regarded as the new Roger Moore was hardly a step in the right direction. With no mate to give him continued employment, Mr. Ogilvy occupied his spare time by writing children’s books. They don’t know too many words, how hard can it be? His last prominent role was as hairdresser to the stars Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn in Death Becomes Her (1992).

The real reason why The Conqueror Worm is considered a breakthrough film is for its unsettling violence. In his appalled horror at the historical sadism of Matthew Hopkins, Reeves went further than any commercial director before him in the kinds of brutality he decided could be shown on the screen. But there is no wallowing in horror, no actual enjoyment of what the film purports to condemn, as is so common in the visceral horror films of today. Rather, this is a sombre assessment of the reality of pain, and its ability to corrupt both givers and receivers. It’s a deeply disturbing film, even when viewed in the cut version which, for several decades, was the only version screened in Australia and the UK – the torture of the heroine with needles in the kidneys was made barely visible, and the dismemberment of Hopkins with an axe was curtailed as well.

The real reason why The Conqueror Worm is considered a breakthrough film is for its unsettling violence. In his appalled horror at the historical sadism of Matthew Hopkins, Reeves went further than any commercial director before him in the kinds of brutality he decided could be shown on the screen. But there is no wallowing in horror, no actual enjoyment of what the film purports to condemn, as is so common in the visceral horror films of today. Rather, this is a sombre assessment of the reality of pain, and its ability to corrupt both givers and receivers. It’s a deeply disturbing film, even when viewed in the cut version which, for several decades, was the only version screened in Australia and the UK – the torture of the heroine with needles in the kidneys was made barely visible, and the dismemberment of Hopkins with an axe was curtailed as well.

In The Conqueror Worm, the cruelty is artistically justified, even necessary, but its significance in the history of cinema is, in part, that it was one of the key films that opened the way to ever more explicit gore at the horror end of the fantasy movie spectrum. It’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

In The Conqueror Worm, the cruelty is artistically justified, even necessary, but its significance in the history of cinema is, in part, that it was one of the key films that opened the way to ever more explicit gore at the horror end of the fantasy movie spectrum. It’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews