SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“In 16th-century Prague, a Jewish rabbi creates a giant creature from clay, called the Golem, and using sorcery, brings the creature to life in order to protect the Jews of Prague from persecution.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

The Gothic tradition had always been stronger in Germany than anywhere else, ever since the Romantic Movement at the beginning of the Nineteenth Century. At the heart of the Gothic was a revolt against the rationality and smugness of an increasingly scientific-minded world – a world in which it seemed that everything had an explanation, and order and harmony were to be prized above all. The Gothic tale typically featured an explosion of madness or horror into the lives of ordinary people, and this was a metaphor for the forces of unreason that simple observation confirmed to exist.

The theme of the Gothic often resolved itself into ancient-versus-modern (as it still does today), and Gothic stories tended to be set in the past, or in some corner of the present where ancient beliefs lingered on. As the shadows grew deeper around Europe, the century-old conventions of Gothic fiction came alive again in the cinema, in the Gothic’s ancestral home (the word referred originally to an ancient German tribe, the Goths).

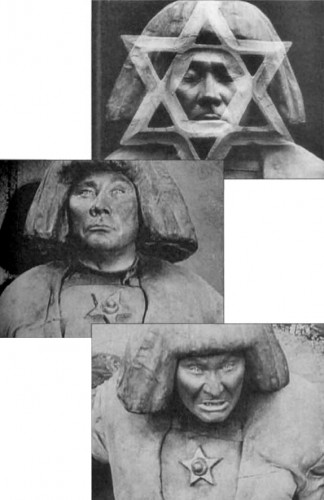

The first hero of Gothic cinema was Paul Wegener, initially as an actor (often in bizarre and fantastic roles) and then as a director. At the age of twenty Wegener decided to end his law studies and concentrate on acting, touring the provinces before joining Max Reinhardt’s acting troupe in 1906. In 1912 he turned to the new medium of motion pictures and appeared in The Student Of Prague (1913). It was while making this film that he first heard the old Jewish legend of the Golem and proceeded to adapt the story to film, co-directing and co-writing the script with Henrik Galeen. The Golem (1914) tells the Jewish myth of the monster without a soul, fashioned out of clay by a daring Rabbi in the Middle Ages to defend the ghetto of Prague against an organised massacre. In the 1914 film, the Golem is dug up in modern times by workmen excavating for a new synagogue. They mistake him for a statue, but he is brought to life by an antiquarian, with whose daughter the monster falls in love. She is appalled and the spurned creature, with its brooding immobile muddy face and soft living eyes, runs amuck and finally falls from a tower. All that now exists of the 1914 film are some photos showing the Golem, played by Wegener himself.

The first hero of Gothic cinema was Paul Wegener, initially as an actor (often in bizarre and fantastic roles) and then as a director. At the age of twenty Wegener decided to end his law studies and concentrate on acting, touring the provinces before joining Max Reinhardt’s acting troupe in 1906. In 1912 he turned to the new medium of motion pictures and appeared in The Student Of Prague (1913). It was while making this film that he first heard the old Jewish legend of the Golem and proceeded to adapt the story to film, co-directing and co-writing the script with Henrik Galeen. The Golem (1914) tells the Jewish myth of the monster without a soul, fashioned out of clay by a daring Rabbi in the Middle Ages to defend the ghetto of Prague against an organised massacre. In the 1914 film, the Golem is dug up in modern times by workmen excavating for a new synagogue. They mistake him for a statue, but he is brought to life by an antiquarian, with whose daughter the monster falls in love. She is appalled and the spurned creature, with its brooding immobile muddy face and soft living eyes, runs amuck and finally falls from a tower. All that now exists of the 1914 film are some photos showing the Golem, played by Wegener himself.

The film helped to create an appetite for filmed horror in Germany. Also, during the war, it was safer to film indoors, and studio conditions always emphasise the fantastic over the realistic element of cinema. Wegener went on to make a series of fairy tales, but he returned to a longer and grander version of the Golem story in 1920. This second Golem (subtitled How He Came Into The World), which still exists in an 85-minute version, returned to the original story of Rabbi Loew, who creates the Golem to save the ghetto from disaster. The Rabbi is unable to control his creature, who resembles an incarnation of some juggernaut-like natural force. The Golem breaks through the ghetto gate into the world outside, where a pretty little Aryan girl (significantly) offers him an apple and then plucks the Star Of David from his chest, and he once again becomes no more than a dead clay statue. Young German maidens dance and play on the body, which is then ceremoniously carried back into the ghetto by the Jewish leaders.

The film helped to create an appetite for filmed horror in Germany. Also, during the war, it was safer to film indoors, and studio conditions always emphasise the fantastic over the realistic element of cinema. Wegener went on to make a series of fairy tales, but he returned to a longer and grander version of the Golem story in 1920. This second Golem (subtitled How He Came Into The World), which still exists in an 85-minute version, returned to the original story of Rabbi Loew, who creates the Golem to save the ghetto from disaster. The Rabbi is unable to control his creature, who resembles an incarnation of some juggernaut-like natural force. The Golem breaks through the ghetto gate into the world outside, where a pretty little Aryan girl (significantly) offers him an apple and then plucks the Star Of David from his chest, and he once again becomes no more than a dead clay statue. Young German maidens dance and play on the body, which is then ceremoniously carried back into the ghetto by the Jewish leaders.

The Golem is a richly symbolic narrative drawn from Jewish mythology, but the question remains after the Golem’s ultimate fate is decided in a startling instant at the end of the film: Is this a sympathetic portrait of the oppression Jews faced throughout Europe, in crowded ghettos of twisted lanes and dark hovels? Or is The Golem more so-called ‘proof’ of Jewish necromancy, another in a long line of paranoid fantasies about Jews putting spells on Gentiles (Shylock, Fagin, Svengali, etc.)? For Paul Wegener, the story of The Golem proved so fascinating that he retold it again and again, rewriting it, directing it, and playing the creature himself, in a remarkable artistic quest to understand the tyrannical power of religious myth. The essence of the story was coincidentally to be repeated in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), but that’s another story for another time. I’ll now bid you goodnight and farewell until we again to grope blindly around the bear-trap known as Hollywood for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News. Toodles!

The Golem is a richly symbolic narrative drawn from Jewish mythology, but the question remains after the Golem’s ultimate fate is decided in a startling instant at the end of the film: Is this a sympathetic portrait of the oppression Jews faced throughout Europe, in crowded ghettos of twisted lanes and dark hovels? Or is The Golem more so-called ‘proof’ of Jewish necromancy, another in a long line of paranoid fantasies about Jews putting spells on Gentiles (Shylock, Fagin, Svengali, etc.)? For Paul Wegener, the story of The Golem proved so fascinating that he retold it again and again, rewriting it, directing it, and playing the creature himself, in a remarkable artistic quest to understand the tyrannical power of religious myth. The essence of the story was coincidentally to be repeated in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), but that’s another story for another time. I’ll now bid you goodnight and farewell until we again to grope blindly around the bear-trap known as Hollywood for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News. Toodles!

The Golem (1920)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews