SYNOPSIS:

Three schoolgirls and their teacher mysteriously disappear on Valentine’s Day in 1900.

REVIEW:

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) is one of the most famous Australian movies ever made. Based on a novel of the same title by Lady Joan Lindsay, this is the film that launched the career of director Peter Weir (The Truman Show-1998; The Year of Living Dangerously-1982). It is internationally renowned and has something of a legendary reputation.

Picnic is not exactly a horror movie, but more of a drama with creepy, supernatural overtones. Still, people who like horror movies—-especially Gothic-style slow-burners—-tend to like this film a lot. There’s a good deal of symbolic content, and so, like other films of that nature (Kubrick’s The Shining, Clayton’s The Innocents),fans are still debating about What It All Means more than 40 years after the film’s debut. (My review of the Weir film can be found elsewhere on the site.)

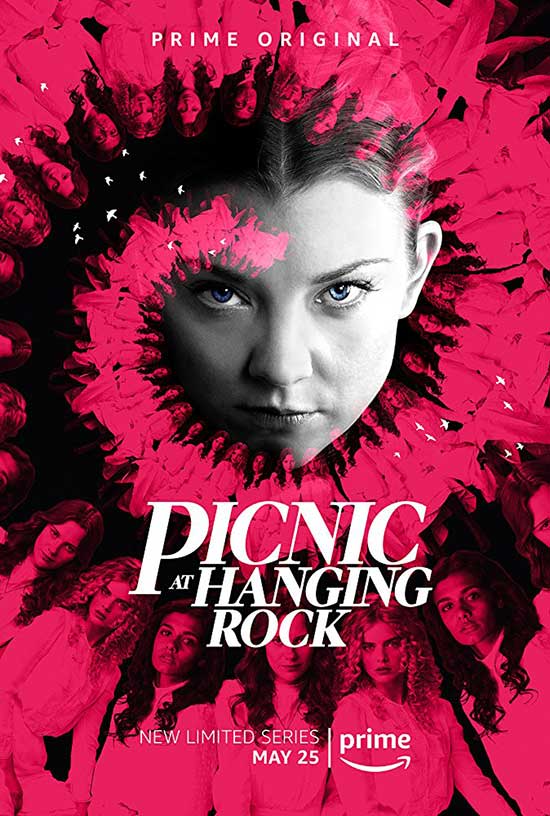

This year, an Aussie television company named Foxtel decided to make a six-part miniseries based on the same tale, which is now streaming at Amazon. The miniseries generated a lot of buzz in the entertainment media, much of it positive, although reviewers at the Internet Movie Database (IMdB)only give it a 6.2 out of 10 rating.

The basic bones of the story are still there, albeit wrenched and tarnished in a grotesque way. A gaggle of teenage girls and two of their teachers leave their repressive Victorian-era girls’ school to picnic at a site near a famous volcanic outcropping called Hanging Rock.

After the picnic, four girls try to climb the massive, mysterious outcropping, but only one returns. Miss McCraw, one of their teachers, also disappears on the rocks, without a trace. Eight days later, one of the missing girls is found amidst the rocks, unharmed except for damage to her hands, with no explanation of how she managed to survive eight days in the wild without food or water.

Unfortunately, the writers and directors (there were three different directors) prove repeatedly that they don’t understand the source material or what the author of the famous novel was trying to say.

The first and most obvious problem with the miniseries is that it tries to stretch a very short novel (it can be read in a couple of sittings) into a nearly six-hour format. The writers/directors pad out the story with lots of confusing flashbacks, extended nightmarish dreams, and wholly invented back-stories for the major characters. The back-story flashbacks make the going very tedious and add nothing to the overall story; on the contrary, the writers have taken a tale that’s supposed to be otherworldly and at least somewhat allegorical, and turned it into a trashy, vulgar soap opera. The symbolism and enigmatic nature of the Weir film has been completely lost, and so has the haunting aura of creepiness and mystery.

The book and the original film were meant to be, at least partially, a meditation on the culture clash of Victorian female propriety and the ancient, alien land that the girls’ British ancestors colonized. This theme has been thrown overboard by the miniseries, so that the missing girls could be turned into stereotypical, 21st Century archetypes that wouldn’t be out of place in a typical American production about nasty high school girl cliques, a la Mean Girls (2004) or even High School Musical (2006). The sexual content has been turned up to eleven, and a vague lesbian theme that was only hinted about in the book and film, is now “in your face.” There’s nothing wrong with that, but that’s not what the source material was meant to be.

Among the worst changes is to the character of Miranda, the leader of the missing girls. Miranda is supposed to be an archetype of the ideal Victorian woman-—modest, kind, charming, graceful, and sweet. She is named after the virtuous daughter in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and she is almost never thought about or spoken about in the Weir film without an image of a swan appearing somewhere in the frame. (The book also explores the swan imagery.) Her French teacher refers to her as a “Botticelli angel.” There’s a vague suggestion that Miranda is a creature so rare, graceful, and beautiful that she’s just not meant for this world, which is why she eventually disappeared without a trace.

However, the miniseries turns this Miranda into a strident, angry proto-feminist who neither looks nor acts like a “Botticelli angel.” In one of her most memorable scenes, she deliberately pisses into a chamber pot in full view of a straight-laced Bible Studies teacher she doesn’t like. For anyone familiar with the film or the book, that pissing scene is really, really, hard to forget—-or forgive. Nevertheless, the French teacher still repeats the line about the Botticelli angel because it’s one of the most famous lines from the book and the Weir film, even though it doesn’t apply to this vulgar new Miranda in any way, shape, or form.

The same thing happens later in the story, when an orphan girl named Sarah is likened by one of the other missing girls to a dying fawn with big, scared eyes. The new and “improved” Sarah described in that comment is an unlikable little brat, but the line gets into the script anyways, because it’s one of the most famous from the book and film.

More unforgivable changes have been made to the character of Mrs. Appleyard, the owner of the girls’ school. Mrs. Appleyard, as created by Joan Lindsay, is a straight-laced widow in her late fifties who is driven insane by the disappearances of the girls. She’s something of a villain, but she has sympathetic qualities as well.

However, the miniseries shaves 20 years off of Mrs. Appleyard’s age and sexes her up pretty heavily (she’s played by Natalie Dormer of Game of Thrones.) Mrs. Appleyard is now a cartoonish villain who behaves viciously and cruelly to her girls for seemingly no reason at all, except that someone was mean to her when she herself was a girl. All subtleties in her character have been relentlessly sanded away.

The missing Miss McCraw, a middle-aged, very eccentric math teacher who, in the book and film, literally cares for nothing but math and science, has been turned into a much-younger, sex-focused lesbian who teaches art, and keeps a primitive Victorian dildo in her personal effects.

It’s as if no female character in this production can be anything but sex-obsessed and stridently “feminist”—and therefore, boring. It’s actually anti-feminist in a way, because the new female characters are cookie-cutter conformists and shorn of any hint of quirkiness or individuality.

To sum it all up, my advice to would-be viewers is to skip the miniseries and just watch the film (or read the book.)

NOTE ON THE FILM’s DVD: Sadly, Weir chopped seven minutes out of the original theatrical version for the Criterion DVD in 1998, a move that enraged many of the film’s fans.

Consequently, U.S. viewers can’t access the theatrical version easily. There’s a 1990 VHS tape floating around on third-party seller sites that may have the original cut on it, but I haven’t watched it so I can say for sure. British viewers can buy a DVD set with both versions.

4/10

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews