SYNOPSIS:

“At Princeton University, John Nash struggles to make a worthwhile contribution to serve as his legacy to the world of mathematics. He finally makes a revolutionary breakthrough that will eventually earn him the Nobel Prize. After graduate school he turns to teaching, becoming romantically involved with his student Alicia. Meanwhile the government asks his help with breaking Soviet codes, which soon gets him involved in a terrifying conspiracy plot. Nash grows more and more paranoid until a discovery that turns his entire world upside down. Now it is only with Alicia’s help that he will be able to recover his mental strength and regain his status as the great mathematician we know him as today.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

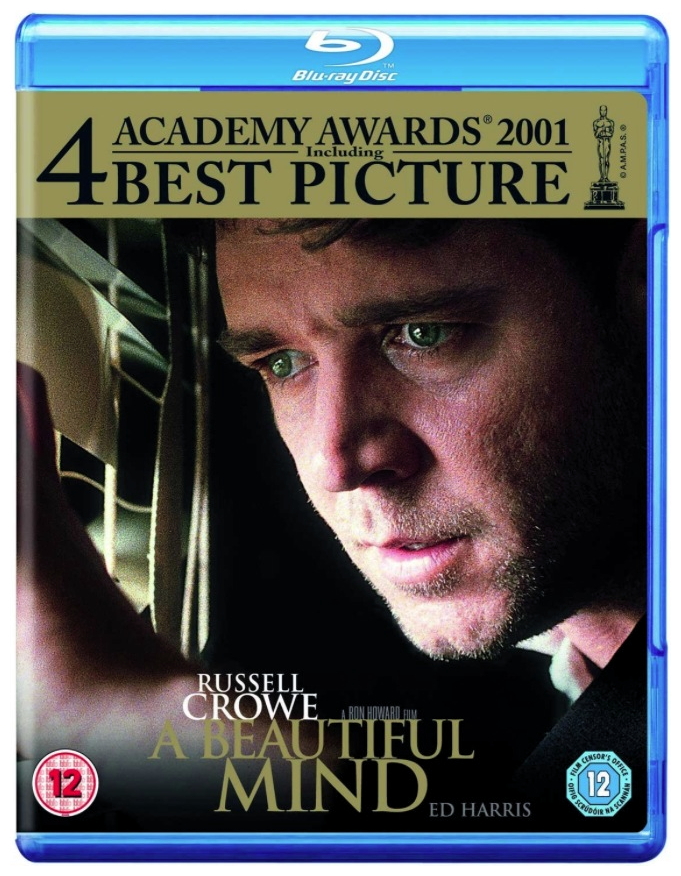

There are two schools of thought pertaining to the treatment of madness in the cinema. One is to observe it from the outside, as a medical condition that can be understood and ultimately overcome. The second involves an intimate and messy depiction of craziness conveyed through the actual filmmaking process, where the form becomes one with the state of mind of characters who have little cognisance of their own condition. For director Ron Howard, schizophrenia was a subject ripe for cinema. A way of conveying emotions such as love, hate, anger, fear and frustration under a Hollywood screenplay paradigm suited to themes associated with redemption. In short, an obstacle the hero must hurdle in his ongoing pursuit of greatness. Opting for a conventional approach to the subject of schizophrenia, embodied here by mathematics genius John Nash (Russell Crowe), Howard relies on his favourite premise – the journey of an outsider from the ordinary to the great – a premise tailor-made for both the Academy Awards and the mainstream market, and it’s no surprise A Beautiful Mind (2001) was popular with both.

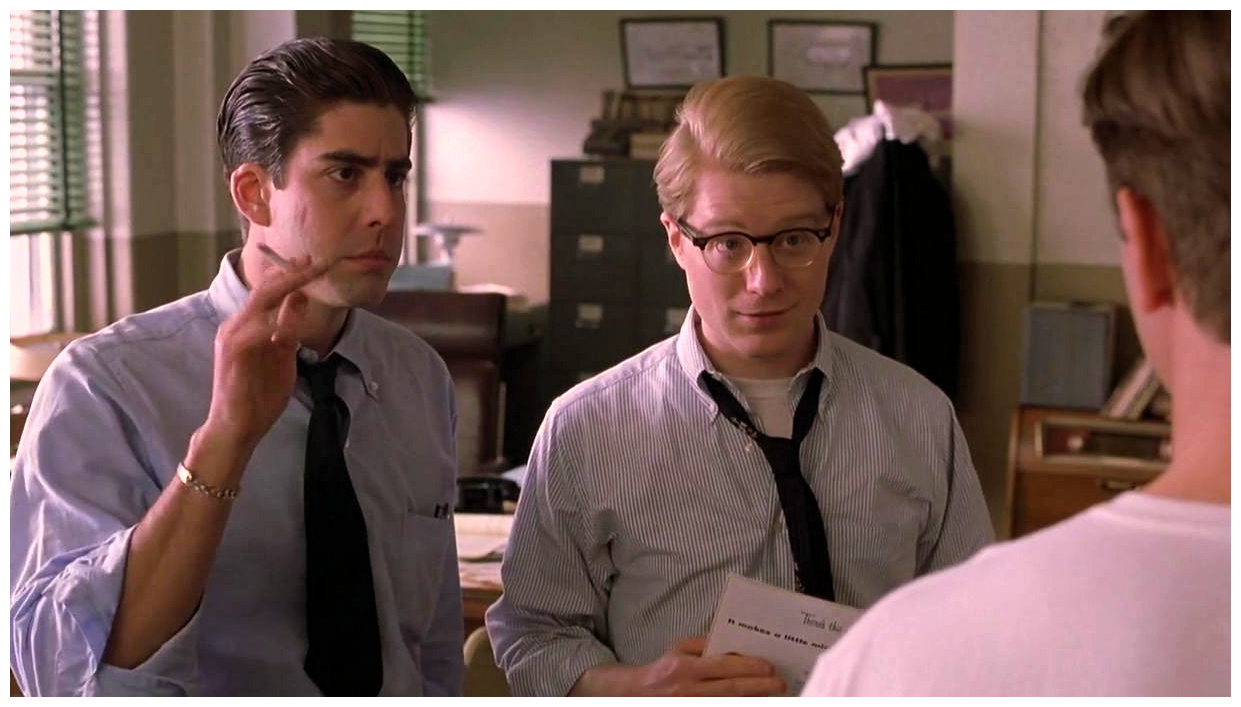

Circumnavigating the various delusions, fantasies and characters labouring in Nash’s psyche for most of his life, the movie charts his path from an arrogant college scholar through to his days as a Princeton professor, married man and father. Although a long journey, A Beautiful Mind is a rewarding experience detailing the idiosyncrasies of a man not steeped in social skills, but blessed with a gift that eventually becomes a curse, especially when he sees fit to participate in confidential late-night assignments for the government that may or may not be figments of his imagination. When he meets vivacious student Alicia (Jennifer Connelly), Nash soon finds himself falling in love and getting some long-anticipated action (some of the funnier bits in the movie come courtesy of his hopeless approach to courtship). However, their relationship undergoes various strains, which includes a trip to the nuthouse where he rids himself of a planted device, while on various occasions he goes off into an orbit of his own invention.

One of the more horrible moments sees his helpless newborn baby left unsupervised in a bathtub as running water slowly rises up, threatening to engulf the child. Like the old adage, that behind every great man is an even greater woman, Nash owes much of his status as an enduring personality to his long-suffering wife. Indeed, Jennifer Connelly gives one of her finest performances of her career as a quietly acquiescing presence, equal in beauty as she is in intellect, further proven by each of the pitch-perfect acting choices Connelly makes in front of the camera. In fact she often outshines Crowe, through nothing other than subtle restraint. Ed Harris plays a shady figure by the name of Parcher, a mysterious menacing character defined by a snap-brim fedora hat. Unfortunately for Harris (one of the world’s best actors) he appears hopelessly stranded in the film playing second fiddle to Crowe’s bombastic array of mannerisms.

Furthermore, Crowe’s performance as Nash is one of the movie’s biggest disappointments. It’s a mannered piece of so-called de-glamourised research, constructed mostly in the editing suite, with the actor stuttering and stumbling through a host of awkward big screen machinations. Even the screenplay seems to convey madness better than any of Crowe’s ham-fisted emoting. Anyone who would turn up late for a date with Jennifer Connelly (like Crowe’s Nash does on numerous occasions) is surely more than ready for a straightjacket fitting with most costume departments. In the annals of cinema, the greatest performances to portray movie madness remain Gena Rowlands‘ tour-de-force of naturalism in her husband John Cassavettes‘ seldom-seen masterpiece A Woman Under The Influence (1974), and the baroque creepiness of Anthony Perkins‘ introverted motel clerk in Alfred Hitchcock‘s timeless shocker Psycho (1960).

As superb examples of manic behaviour, these memorably mad performances incarnate craziness in the respective examples of movie drama and genre, as both actors achieve a hyper-intensity initiated firstly via careful interaction with the other players, secondly with a deft harmony in front of the camera and, thirdly, a sincerity to both the character and human desire. In A Beautiful Mind, Crowe finds very little balance with either of these elements, performing a one-man show where he finds more chemistry with the furniture rather than any of his onscreen cohorts. When the real John Nash visited the set, Crowe said later that he was fascinated by the way he moved his hands, and he tried to do the same thing in the movie. He thought it would help him get into the character: “I had made the decision not to pursue endless conversations with Nash. What we realised was that there were a lot of areas of his life that we wanted to go into, that he hadn’t considered significant. So therefore his memory banks were not necessarily full of the stuff that we wanted to know.”

“Plus most of what we were going to do was going to be about deduction, we were filling in a lot of blanks. We were looking at a 74-year-old man who spent the middle part of his life – 35 years – in hospitalisation and medication. When you look at the disease and you understand it, you see the difference that happens in physicality, the difference that happens in the tone of people’s voices and their body language. We realised that the man we see now is a completely different person from who he was at 22. None of us are capable of being true witnesses to our own lives, because we tend to give it a certain amount of distance, forgive ourselves for certain motivations or decisions that we might have made at certain ages. So he was going to be a false witness. We knew that from very essential, simple questions. ‘Have you ever smoked a cigarette?’ – ‘No, I have never smoked’. Nash smoked for about seven or eight years. ‘Have you ever worn a beard?’ – ‘No, I have never worn a beard’. We have photographic evidence that he wore a beard in Europe. So it got to a point where we couldn’t necessarily rely on him.”

“Now, that’s not being dismissive of him, that is just to make you understand what we were trying to do. So we took the broader facts of his life like, where was he born? West Virginia. Okay, so given that our movie doesn’t have him living in Europe or Boston for the years that he did, we don’t explore the fact that he wanted to become a Swiss citizen and give up his American citizenship. We don’t go into those places because they are not important to the story of humanity that we are trying to tell. So we started with him having been born in West Virginia which was the basis for the vocal inflection that we use in this movie.” Amidst Howard’s conventional biopic approach, he has very few signatures as a director apart from a Doctor Seuss reference. Most of the regal interiors are fog-filtered to create a misty atmosphere akin to Nash’s subconscious, emphasised with sweeping crane shots. Meanwhile, most of the emotional plot points are heightened by dolly moves onto the actors faces to induce tears from the audience.

The nadir of this comes when an obligatory Hollywood heart-over-head speech is delivered by Connelly. The stars embrace while the camera backtracks slowly out of the window to signify a holy moment of grace. Howard: “I’ve always loved the story and feel that we did it justice. I don’t know how perfect or imperfect the movie is, but I never tired of looking at it. I was very disappointed, melancholy when we finished the whole process, more than on any movie I can remember. It presented so many intriguing choices and I’m sure I didn’t get them all right, but they were interesting to make.” That being said, composer-for-hire James Horner contributes an impressive and sombre score with a dark refrain that seems to get more poetic each time Howard remembers to drop it in over the images. The problem Howard hasn’t quite come to grips with yet is this – Hollywood already has a Steven Spielberg (one is more than enough), and a Robert Zemeckis (Spielberg with wit), leaving Howard in a precarious position somewhere between future Disney assignments and disease-of-the-week television dramas.

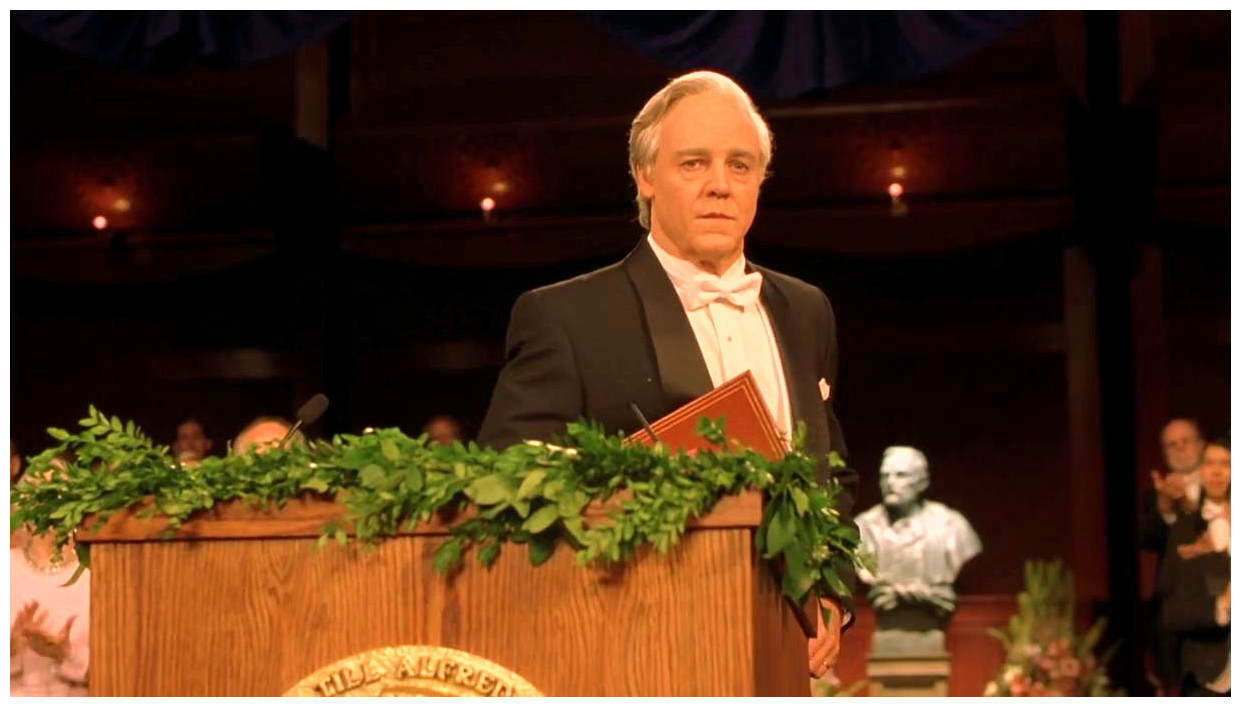

Howard’s movies always have a strong core idea but usually stumble at a point where something more demanding is required of the audience, with the challenge being the viewer’s threshold for the obvious. In the tradition of the biographical Oscar-winning tearjerker – see Shine (1996) – there is a heavy scene where the hero receives a standing ovation from an important institution (the Nobel Prize) and another where he finally discovers he has gained the respect of his peers, namely a set of writing pens from Princeton’s close-knit and conservative academia. Insofar as the awareness of schizophrenia is presented as a seesaw of desperate emotions, the answers provided in the movie are not as compelling as the questions that perhaps should have been asked. At what cost genius? Where does love stop and dependency begin? The core romance suffers the most here, lacking the toughness prescribed the topsy-turvy conflicts continually threatening the Nash marriage. However, there is a force of emotional honesty presented here, imbued with hope and some much-needed ambiguity as Nash eventually reaches an interesting compromise with each of his personal demons.

By the end of A Beautiful Mind, Howard does manage to present the enigmatic figure of Nash as a problem with no easy solution, an interesting decision that should be ultimately championed rather than criticised. On the two-disc DVD I viewed, disc one features an informative commentary with Ron Howard and producer Ron Grazer, as well as extensive deleted scenes. Disc two has a number of featurettes: A Beautiful Partnership is an interview with Howard and Grazer; Development Of The Screenplay; Meeting John Nash; Accepting The Nobel Prize; Casting Russell Crowe & Jennifer Connelly; The Process Of Age Progression; Storyboard Comparisons; and Digital Effects. Right now I’ll quickly wrap up this article and politely request your company next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier again with another feather plucked from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News! Toodles!

A Beautiful Mind (2001)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews