SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“The mathematician Maximillian Cohen is tormented by a severe migraine since he was a kid, and he uses many pills to reduce his painful headaches. He is a lonely man, and his only friend is his former professor Sol Robeson. Max has the following assumptions, which rules his life: (1) Mathematics is the language of nature; (2) Everything around us can be represented and understood from numbers; (3) If you graph the numbers in any system, patterns emerge. Therefore there are patterns everywhere in nature. Based on these principles, Max is trying to figure out a system to predict the behavior of the stock market. Due to his research, Max is chased by a Wall Street company with obvious interest in the results of his studies, and by a Chasidic Torah scholar, who believes that this long string of numbers is a code sent from God.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

After decades of relative obscurity, math is suddenly hip, or so it would seem. Since the turn of the century, books about mathematics and mathematicians have made their ways onto the bestseller lists, television series about mathematics have been aired, radio programs have carried stories about mathematics, and newspapers and magazines have discovered that large numbers of their readers are interested in articles about mathematics. Within the past eight months, math has even made its way into the movies, with two feature films in which not only was the lead character a mathematician, but we even see mathematics portrayed on the silver screen: The Imitation Game (2014), in which British mathematician Alan Turing is tasked with cracking Nazi Germany’s Enigma code that would help the Allies win World War Two, and The Theory Of Everything (2014), about the life and hardships faced by theoretical physicist and mathematician Stephen Hawking. Is this the start of a trend? Math in the movies is certainly unusual, but The Imitation Game and The Theory Of Everything are hardly breaking new ground. Dustin Hoffman‘s character in Straw Dogs (1971) was a mathematician, and the mathematics shown on the blackboard at one point is the genuine article. The director was Sam Peckinpah, so you can guess what kind of ending that film had.

In the romantic comedy It’s My Turn (1980), star Jill Clayburgh plays a college math professor, and the film opens with her lecturing to a graduate mathematics class. She proves a well-known theorem of homological algebra. It’s all correct, but the reason for making these characters mathematicians is simply to establish them as a highly intelligent intellectuals. Math plays no other role in these films, but there are other films since (both fictional and biographical) that have treated mathematicians with a modicum of respect: A Hill On The Dark Side Of The Moon (1983), Sneakers (1992), ‘N’ Is A Number: A Portrait Of Paul Erdos (1993), Antonia’s Line (1995), Infinity (1996), The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996) and Good Will Hunting (1997). In Contact (1997) star Jodie Foster makes a good job of defining prime numbers, explaining how primes provide a good way to communicate with intelligent aliens, although using Pi would probably work better. Which brings me rather smoothly to Darren Aronofsky‘s first feature-length film Pi (1998).

In the romantic comedy It’s My Turn (1980), star Jill Clayburgh plays a college math professor, and the film opens with her lecturing to a graduate mathematics class. She proves a well-known theorem of homological algebra. It’s all correct, but the reason for making these characters mathematicians is simply to establish them as a highly intelligent intellectuals. Math plays no other role in these films, but there are other films since (both fictional and biographical) that have treated mathematicians with a modicum of respect: A Hill On The Dark Side Of The Moon (1983), Sneakers (1992), ‘N’ Is A Number: A Portrait Of Paul Erdos (1993), Antonia’s Line (1995), Infinity (1996), The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996) and Good Will Hunting (1997). In Contact (1997) star Jodie Foster makes a good job of defining prime numbers, explaining how primes provide a good way to communicate with intelligent aliens, although using Pi would probably work better. Which brings me rather smoothly to Darren Aronofsky‘s first feature-length film Pi (1998).

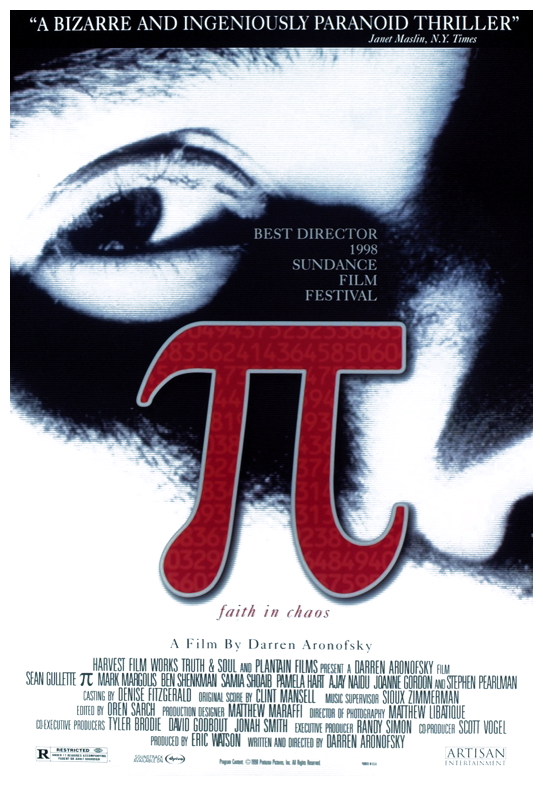

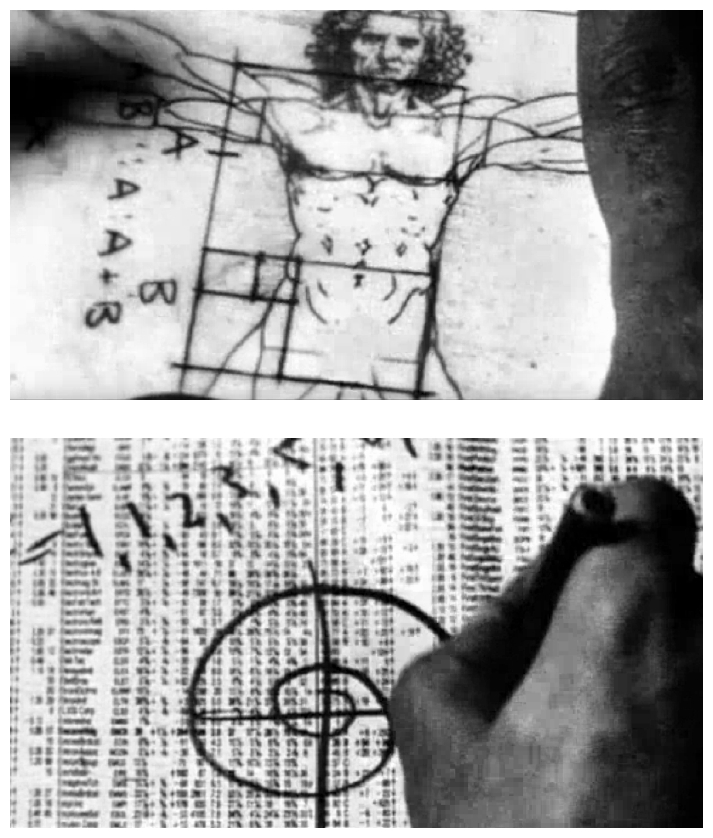

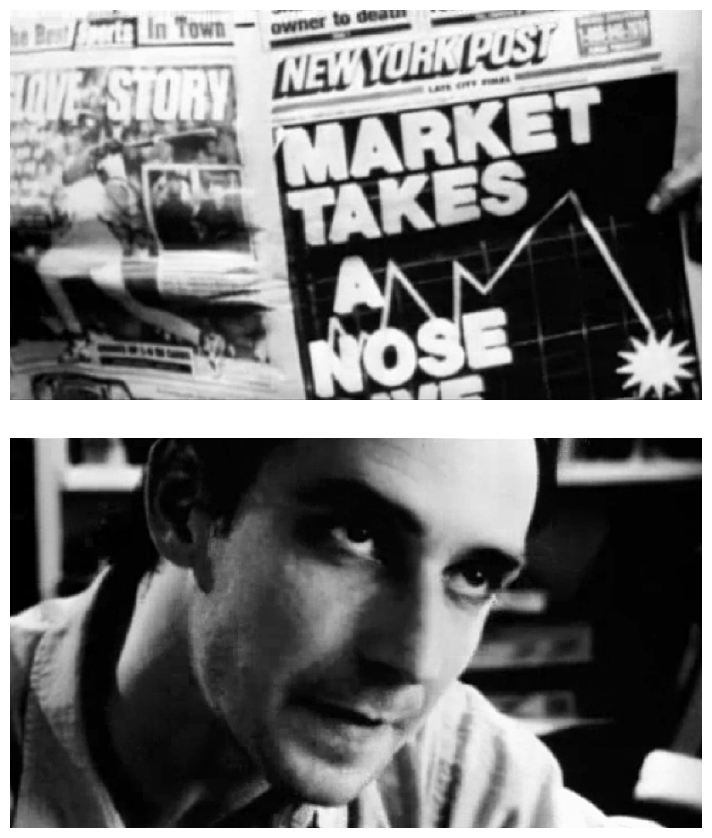

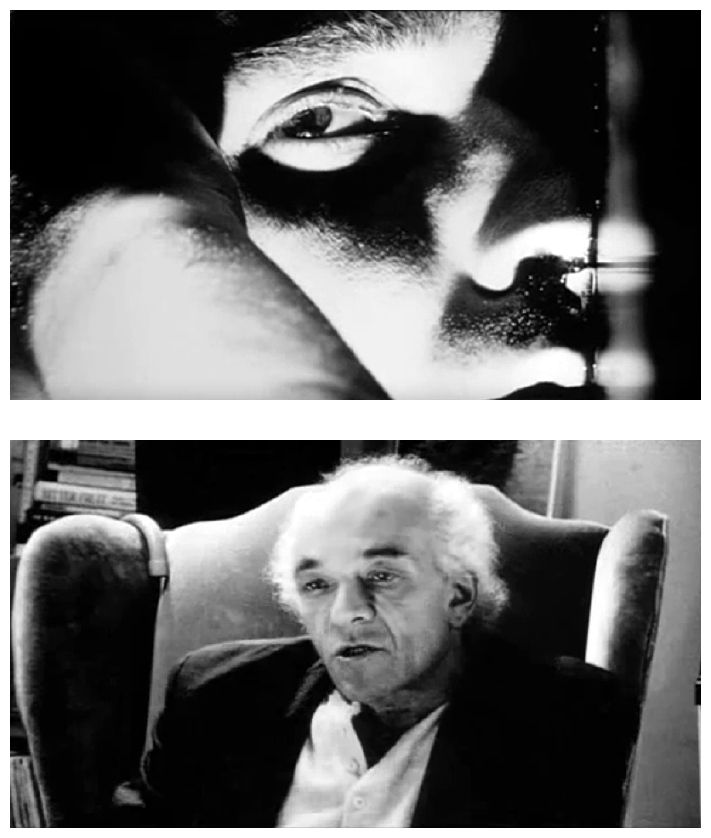

The ‘Faith In Chaos’ tag-line on the poster gives a definite flavour of the contradictions and conflicts depicted in this number-crunching-meets-end-of-the-millenium movie, and efficiently conveys the core themes of number theory and religion while simultaneously suggesting a sense of mystery. The chaos is all focused on the struggles of mathematician Max Cohen (Sean Gullette) as he looks for patterns in the random numbers of the stock exchange while failing to communicate with the people around him: his mentor Sol Robeson (Mark Margolis), Lenny the Hasidic Jew studying the Torah (Ben Shenkman), his neighbours, and the persistent corporate suits who want to employ him. Pi is rightly acclaimed as a masterpiece of subjective cinema. The opening titles – a montage of brain cells and mathematical diagrams superimposed on the streaming digits of the infinite number for pi – take the viewer directly into the protagonist’s mind. The story Max relates about looking directly into the sun when he was a child also hint most strongly this is a failure of vision.

The ‘Faith In Chaos’ tag-line on the poster gives a definite flavour of the contradictions and conflicts depicted in this number-crunching-meets-end-of-the-millenium movie, and efficiently conveys the core themes of number theory and religion while simultaneously suggesting a sense of mystery. The chaos is all focused on the struggles of mathematician Max Cohen (Sean Gullette) as he looks for patterns in the random numbers of the stock exchange while failing to communicate with the people around him: his mentor Sol Robeson (Mark Margolis), Lenny the Hasidic Jew studying the Torah (Ben Shenkman), his neighbours, and the persistent corporate suits who want to employ him. Pi is rightly acclaimed as a masterpiece of subjective cinema. The opening titles – a montage of brain cells and mathematical diagrams superimposed on the streaming digits of the infinite number for pi – take the viewer directly into the protagonist’s mind. The story Max relates about looking directly into the sun when he was a child also hint most strongly this is a failure of vision.

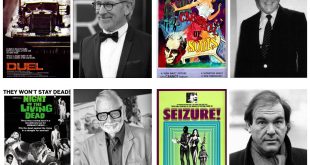

Pi is a film with a single narrative point of view – Max’s – everything and all the viewer sees is what he experiences. Aronofsky uses a range of cinematic effects to enhance this association with Max’s state of mind. When Max walks the streets, Aronofsky employs a camera attached to the actor, commonly referred to as a Snorricam. This separates Max from his environment, depicting his isolation and alienation. The subtle changes in film speed strangely disorient the viewer. The plot is also punctuated by Max’s migraines, each following a repeated pattern and each escalating in severity, from Max’s twitching thumb to desperate scramble for drugs at onset, culminating in hallucination and final fade to white. Anyone who has ever suffered from migraines will recognise the experience, if not the actual set of symptoms. So convincingly does Aronofsky capture the attacks, these sequences become painful within themselves.

Pi is a film with a single narrative point of view – Max’s – everything and all the viewer sees is what he experiences. Aronofsky uses a range of cinematic effects to enhance this association with Max’s state of mind. When Max walks the streets, Aronofsky employs a camera attached to the actor, commonly referred to as a Snorricam. This separates Max from his environment, depicting his isolation and alienation. The subtle changes in film speed strangely disorient the viewer. The plot is also punctuated by Max’s migraines, each following a repeated pattern and each escalating in severity, from Max’s twitching thumb to desperate scramble for drugs at onset, culminating in hallucination and final fade to white. Anyone who has ever suffered from migraines will recognise the experience, if not the actual set of symptoms. So convincingly does Aronofsky capture the attacks, these sequences become painful within themselves.

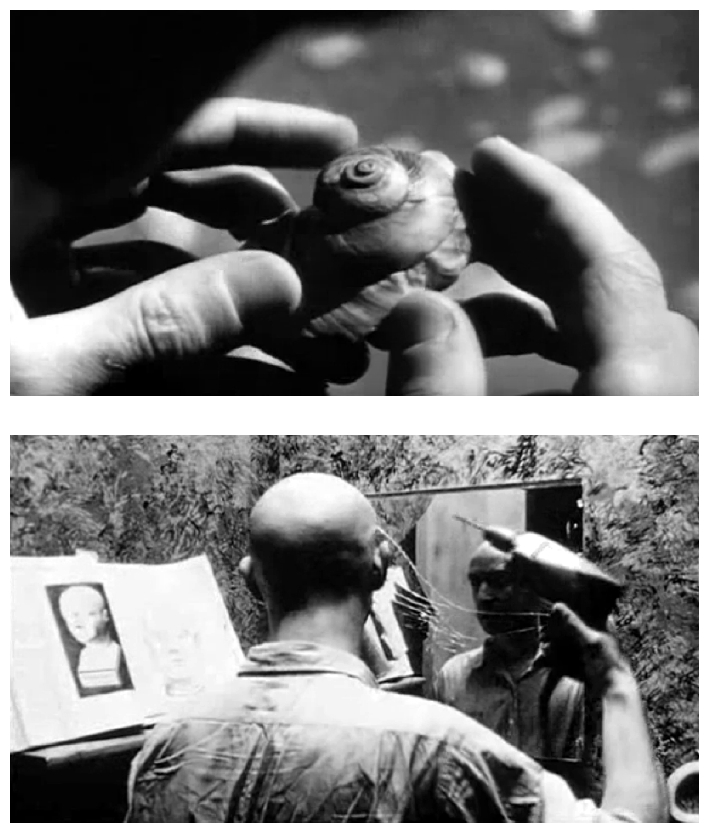

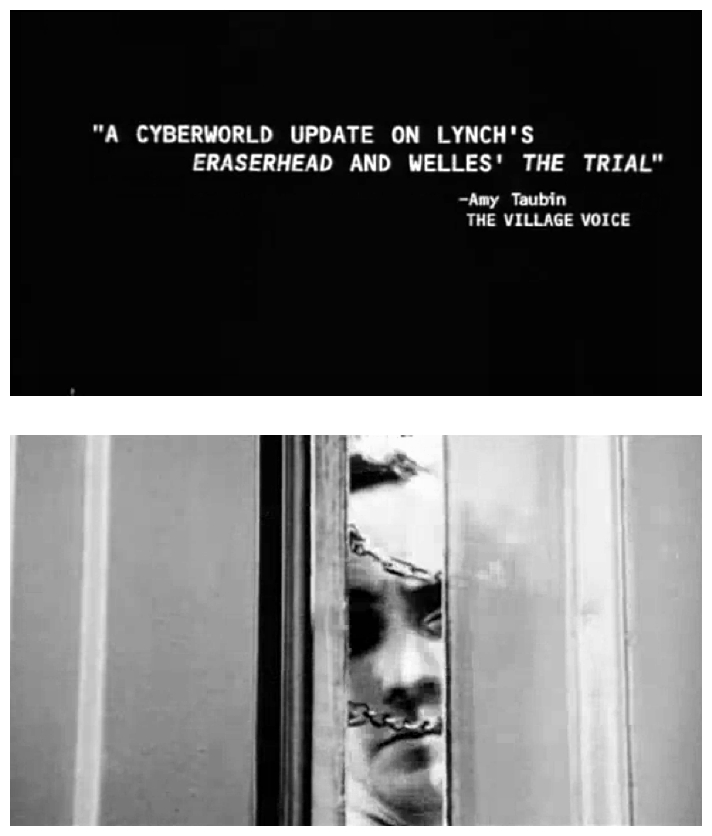

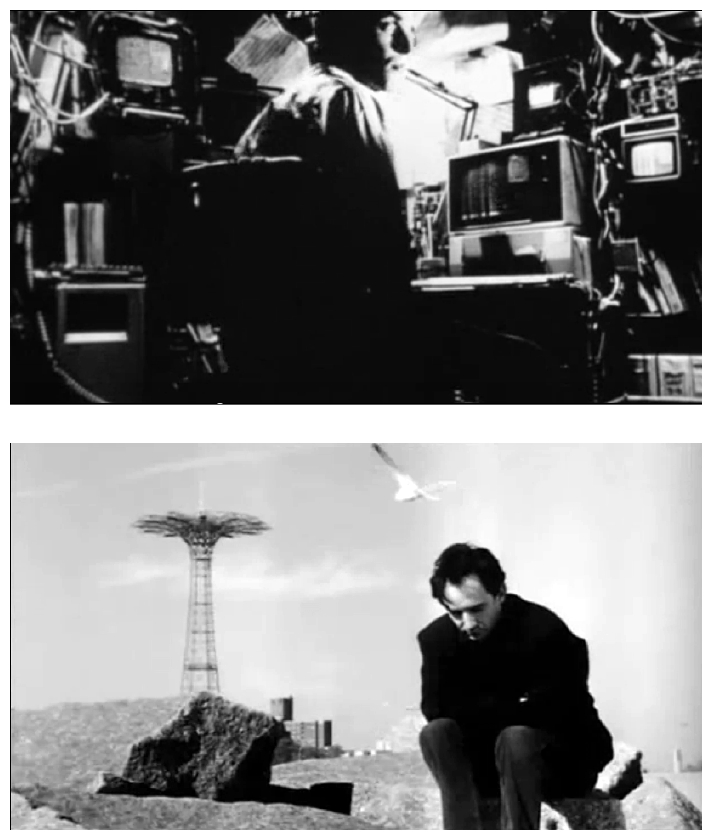

The subjectivity also confounds any sense of truth in the narrative. Is this a depiction of true events, hallucination, or Max’s paranoia? Whatever the answer (and this is clearly left open to individual interpretation), the film conveys more atmosphere and emotion in its black-and-white cinematography than most mainstream movies. It is rich in imagery (from spiral shells to Sol’s Go game board), metaphor (Max’s room is so packed with computer equipment that he seems to become part of the machine), allusion (ants are the literal bugs in Max’s program) and allegory (like Icarus flying too close to the sun). Of course, there have been plenty of stories in the past dealing with people who have been driven mad by hearing God’s true name, voice, number, whatever, but Pi is all about mood and little more, executed so proficiently that mood is all it really needs to be.

The subjectivity also confounds any sense of truth in the narrative. Is this a depiction of true events, hallucination, or Max’s paranoia? Whatever the answer (and this is clearly left open to individual interpretation), the film conveys more atmosphere and emotion in its black-and-white cinematography than most mainstream movies. It is rich in imagery (from spiral shells to Sol’s Go game board), metaphor (Max’s room is so packed with computer equipment that he seems to become part of the machine), allusion (ants are the literal bugs in Max’s program) and allegory (like Icarus flying too close to the sun). Of course, there have been plenty of stories in the past dealing with people who have been driven mad by hearing God’s true name, voice, number, whatever, but Pi is all about mood and little more, executed so proficiently that mood is all it really needs to be.

Produced on a small budget of US$60,000, the film grossed more than US$3 million in America alone (despite limited theatrical release) and has sold steadily on DVD ever since. A truly independent production, most of the budget was raised in the form of individual hundred-dollar contributions from the Aronofsky’s friends and family, and his own mother did the catering. When the film was later bought by Artisan Entertainment for US$100,000 each contributor received a US$150 return on their investment. All the exteriors were filmed guerilla-style, no location permits were secured, so the crew always had to have one person constantly on the lookout for police. As for Max’s room, where most of the film takes place, many of the props on the set were hot-glued together which, combined with the hot lights and the cramped quarters, caused a few of crew to become nauseous from the smell. Hey, that’s what independent film-making is all about!

Produced on a small budget of US$60,000, the film grossed more than US$3 million in America alone (despite limited theatrical release) and has sold steadily on DVD ever since. A truly independent production, most of the budget was raised in the form of individual hundred-dollar contributions from the Aronofsky’s friends and family, and his own mother did the catering. When the film was later bought by Artisan Entertainment for US$100,000 each contributor received a US$150 return on their investment. All the exteriors were filmed guerilla-style, no location permits were secured, so the crew always had to have one person constantly on the lookout for police. As for Max’s room, where most of the film takes place, many of the props on the set were hot-glued together which, combined with the hot lights and the cramped quarters, caused a few of crew to become nauseous from the smell. Hey, that’s what independent film-making is all about!

The number Max is searching for is 216 digits long. 216 is 6 x 6 x 6 = 666 which is the ‘Number Of The Beast’ according to the Book of Revelation. There have been a increasing number (pardon the pun) of films concerning maths and mathematicians since the release of Pi, including A Beautiful Mind (2001), Enigma (2001) and Agora (2009). Terry Gilliam‘s The Zero Theorem (2013) contains more than a few similarities to Aronofsky’s film, centering as it does on a reclusive computer genius named Qohen (Christopher Waltz) working on a formula to determine whether life holds any meaning, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll politely invite you to meet me here next week on Horror News when I have another opportunity to inflict a pain beyond pain, an agony so intense it shocks the mind into instant mashed potato! Toodles!

The number Max is searching for is 216 digits long. 216 is 6 x 6 x 6 = 666 which is the ‘Number Of The Beast’ according to the Book of Revelation. There have been a increasing number (pardon the pun) of films concerning maths and mathematicians since the release of Pi, including A Beautiful Mind (2001), Enigma (2001) and Agora (2009). Terry Gilliam‘s The Zero Theorem (2013) contains more than a few similarities to Aronofsky’s film, centering as it does on a reclusive computer genius named Qohen (Christopher Waltz) working on a formula to determine whether life holds any meaning, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll politely invite you to meet me here next week on Horror News when I have another opportunity to inflict a pain beyond pain, an agony so intense it shocks the mind into instant mashed potato! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews