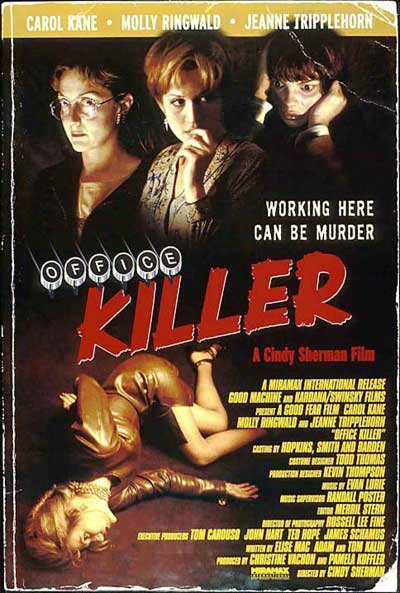

SYNOPSIS:

A mousy office worker accidentally kills one of her coworkers, then proceeds to bump off a few others.

REVIEW:

Photography is, of course, the parentage from which the moving image was born. Consequently, we believe that a masterful understanding and control of still imagery can easily be translated onto celluloid.

This is not always the case – particularly if you have your own style contrary to what the audience you are exhibiting for is accustomed to. For example, if I were a surrealist artist trying my hand in Hollywood film; hoping that the audiences will think outside the box with me then I probably shouldn’t expect a large number of box office returns.

I suppose one could attribute photography with the late great, Sir Alfred Hitchcock – not as a trade but he did overtly display a love for it; he had written picture-based stories for Life magazine once, was synonymous for subjective portraiture with his close-ups of characters and one of his most famous characters, Raymond Burr (James Stewart) from Rear Window was an incapacitated photographer relying entirely on his camera to solve a murder. It’s easy to notice this cinematically in his techniques and fascination with ‘film looking’ – as with voyeurism chiefly – that suggests an appreciation of what a frame can achieve, largely to create suspense.

Subsequently this direction, saturated with Hollywood politics and ideologies, revolutionised film yet never strayed too far from what Hollywood audience have come to know and love so it is understandable that when dealing with suspense within Thriller/Horror that his blueprint is imitated, advertently or inadvertently, in an attempt to emulate his success. Clearly, Cindy Sherman – debutant director with Office Killer (1997) and career photographer – shares a similar path as Hitchcock, thus adopting his proficiency of still imagery whilst attempting to label it as her own. The result is one of her recreating Psycho (1960) essentially except it is in no way as commercially successful.

Where she differs from Hitchcock is that her filmic methods detract largely from the content onscreen and rely on the concept as a whole, especially to establish the comical element within the film. Aesthetically, Office Killer is a neo-noir B-movie highlighted by its low lit through window shade slats proclivities, melodramatic characters and jazz-centric film scoring. Littered with ‘Shermanisms’; representations of females in the workplace and in society; both the office and the cast as a whole are dominated by female parts. This feature is not subtle either; Office Killer focuses on female stereotypes, pungently demonstrated using cutaways of domesticity – making tea, signs of children, dishes waiting to be washed and ironing that disassociate from the ensuing narrative at times. Also, it’s indelibly fascinated by the grotesque and dreamlike states that blur the lines between fiction and reality. Ultimately, Sherman is effectively continuing her artwork on film, minus herself as the principal subject.

Office Killer is a dark comedy but not because of its content. It is in no way laugh out loud funny nor does it intend to be. The closest it ventures to comedy in the familiar sense is through the crooked characters and their tasteless badmouthed interactions with each other. If you find that kind of thing hilarious…then you’re possibly too young to be watching the film…but at least you’ll be happy that you did as it is littered with such sophomoric behaviour.

The notion of a magazine veteran driven to maniacal serial murder by her job is absurdly fanciful and that’s what makes Office Killer, in many respects, comical. The audience (and Sherman) realise that however preposterous it is, it is also irrefutably a minute possibility or, at the very least, a play on the small desire deep within the murky depths of the nine to fiver’s psychosis. This particular approach heralds that Sherman appeal found within her conceptual pieces.

Yet, whilst flexing her influence throughout the film, she must have been aware of the Psycho reference being abducted from the Bates Motel and transplanted to the urban working environment of an office building. There are many: the fact that Dorine Douglas (Carol Kane) – Carrie-esque in her discomfited timidity – lives with a domineering castrating mother as Bates did in Psycho. Like Bates she revels in the company of the dead down in her basement. Furthermore, her homicidal intent is somewhat catalysed by the bloody death of her abusive father, much like Bates.

Dorine herself is based off of Bates; his weird yet charming personality. The character cultivates a hyperreality in which her vile bosses and co-workers become an extension of the repulsive family she clearly hates but must put up with, thus she feels remorseless and justified in her deeds. Bates felt the same as he targeted women who sexually aroused him, disrupting the oedipal fantasy he had constructed around his mother. However, why Dorine feels it necessary to murder EVERYBODY she encounters is a conundrum. She soon becomes a pointless motiveless killer and any linearity her deadly plans had, is lost. Even Bates still had specific reasons for each murder he committed.

Sherman’s peripheral roles suggest the continued replication too. Co-worker and friend, Norah Reed, is her Marion Crane – she has Dorine’s affections. They are friendly and Norah completely trusts Dorine still she finds herself in potential danger. Daniel Birch (Michael Emperioli) strikes as Detective Arbogast as his investigative curiosity puts him in the line of fire. Then there’s Kim Poole (Molly Ringwald) ineffectively portraying a likeness to Lila Crane as she attempts to convince those around her that they are dealing with a serial killer in Dorine.

The indications are so barefaced that I wonder whether Sherman’s objective was to parody Hitchcock’s baby, mocking the stereotypes that his films – Psycho and all – embodied – the right winged inequality that subjected women as objects within the film gaze in early to mid twentieth century cinema. Using Office Killer, she augmented the feminine status to subject effortlessly but, consequently, surrendered a large amount of the ‘Hollywood plausibility’ that would have made her film more profitable. Also, theoretically, employing this shift in gender roles may have assisted the film’s sardonic tone therefore undermining any serious feminist stances.

Office Killer is now available on DVD per Echo Bridge Entertainment

Office Killer (1997)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews