SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

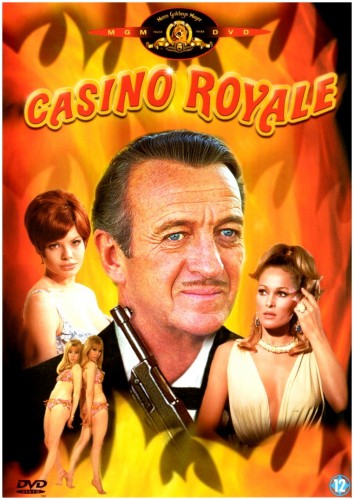

“Sir James Bond is enjoying his retirement when four international agents press him into service again in hopes of smashing SMERSH and topple Le Chiffre at the baccarat tables. Bond is taken in by Agent Mimi (alias Lady Fiona McTarry) who immediately falls in love with him. Bond’s illegitimate daughter, Mata Bond, whose mother was the late Mata Hari, is going to help out. The current agent using the Bond name, Cooper, has his hands full, despite his assistance by beautiful secretary, Moneypenny. 007’s nephew Jimmy Bond is supposedly incompetent. Bond, hoping to clear his name from its current low repute, hires Evelyn Tremble to meet Le Chiffre at the gambling tables at Casino Royale. The world’s richest agent, Vesper Lynd, helps convince Tremble to masquerade as 007.”

REVIEW:

The James Bond films began the trend in which science fiction elements were increasingly incorporated into thrillers during the sixties, a trend which reached boom proportions in the latter half of the decade. Foremost among the Bond imitators were the Matt Helm series of films starring Dean Martin – The Silencers (1966), Murderer’s Row (1966), The Ambushers (1967), The Wrecking Crew (1969) – the two Derek Flint films starring James Coburn – Our Man Flint (1966), In Like Flint (1967) – and the various Man From UNCLE feature films created by combining television episodes and adding extra footage – The Spy With My Face (1965), One Of Our Spies Is Missing (1966), One Spy Too Many (1966), How To Steal The World (1968) – all of which became progressively far-fetched.

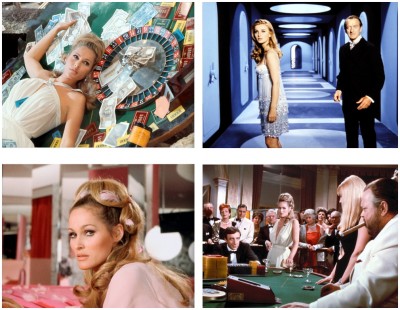

But the most way-out spy film of all was Casino Royale (1967), a bizarre concoction that has virtually nothing to do with the first (and arguably the best) of Ian Fleming‘s James Bond novels. Ranging from surreal black comedy to pure slapstick, the movie boasts remarkably little in the way of coherent plotting, a fault that was compensated for by the numerous plots and counterplots hatched before and during its turbulent shooting. To begin with it was financed, not by the producers of the regular Bond series, Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli, but by Charles Feldman who just had a huge hit with What’s New Pussycat (1965). The rights of the first novel were originally purchased to produce a live television play starring Barry Nelson as CIA agent Jimmy Bond, Michael Pate as British MI6 agent Felix Leiter, and Peter Lorre as the villainous Le Chiffre. Although a great deal of fun to watch today, it was always considered below-average, both as a James Bond adventure and as a live television play. Lines are flubbed, and both the sound and staged effects are poor at the best of times (in the opening scene for instance, gunshots and their squibs are way out of sync).

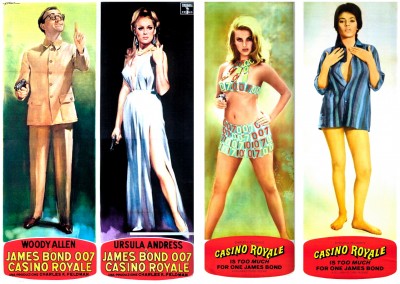

Since Charles Feldman was unable to use Sean Connery in his version, he decided the only possible solution was to send-up the James Bond persona, making Casino Royale a kind of farcical satire with only a very marginal connection to the original novel. Despite having ten writers (including Terry Southern, Woody Allen, Wolf Mankowitz, Ben Hecht and Joseph Heller), five directors and a dream cast that included Peter Sellers, David Niven, Ursula Andress, Orson Welles, Joanna Pettet, Deborah Kerr, Woody Allen, William Holden, Charles Boyer, John Huston, Barbara Bouchet, George Raft, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Peter O’Toole, Sterling Moss, Terrence Cooper, Bernard Cribbins, Ronnie Corbett, Kurt Kaszner, Anna Quayle, Geoffrey Bayldon, John Wells, Derek Nimmo, Geraldine Chaplin, Valentine Dyall, Anjelica Huston, Burt Kwouk, John Le Mesurier, Caroline Munro, David Prowse, Jacqueline Bisset, Alexandra Bastedo and John Bluthal, the movie is a confused concoction in which the secret services of Britain, America, France and Russia meet to discuss how the evil organisation SMERSH can be foiled.

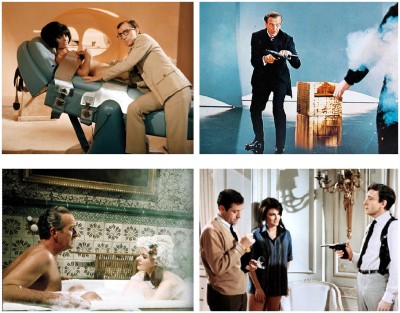

They decide to persuade Sir James Bond out of retirement – by blowing up his country house. ‘M’ is killed in the explosion, and Bond travels to Scotland to console his widow Lady Fiona McTarry and her family. Unbeknownst to Bond, the McTarrys have been replaced by SMERSH agents and…oh, forget it! Suffice to say that, by the climax of this incomprehensible farrago, almost everyone has a go at being James Bond, and ends with Woody Allen as the would-be master of the world, who swallows a pill-sized atom bomb and blows himself (and everybody else) to bits. “Seven James Bonds at Casino Royale, they came to save the world and win a gal at Casino Royale. Six of them went to a heavenly spot, the seventh one is going to a place where it’s terribly hot.”

It was obviously intended to be a ‘fun’ movie like What’s New Pussycat except that on this occasion, not even the cast gave a convincing impression of enjoying themselves, which was undoubtedly the case. Joseph McGrath was originally hired as sole director, a risky choice for a multi-million dollar production as it was his first feature. But he was a personal friend of Peter Sellers who, over Feldman’s better judgment, decided on him as the man most qualified to steer such a vast leaky vessel safely into port. McGrath, however, could not have realised that he would also have to deal with a severe and genuinely founded crisis concerning the actor’s vanity. The crux of the movie (one of only two scenes remaining from the original novel) is a marathon game of baccarat played at Le Torquet between the evil genius behind SMERSH, Le Chiffre (Orson Welles) and Bond – or rather, in the movie version, one of Bond’s many surrogates, Mr. Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers). But Sellers, after a humiliating encounter with the gargantuan American actor-director, became obsessed with the notion that he was going to be upstaged. Like some paranoid chess-master, he felt his performance would suffer from the hostile vibrations of his charismatic co-star. He categorically refused to play the scene in Welles’ presence, and insisted that McGrath first film Welles then, in reverse angle, a reaction shot from himself, and so on.

All of which was perfectly feasible since they would be sitting opposite each other across the baccarat table, except for two problems. Firstly, there was no establishing shot of the two players in the same room. This was fixed in post-production with a couple of seconds of obvious superimposing. Secondly, actors tend to benefit greatly from a form of mutual feedback, even if their personal relations are less than amicable. Sellers, whose work had already been blunted by a string of ‘yes-men’ directors, was now denying himself the indispensable opportunity of playing opposite another actor. His resulting performance in Casino Royale is significantly one of the most featureless and lackluster of his entire career. Sellers decided someone should be blamed and did not indulge in an excess of soul-searching. McGrath had to go and so he departed, along with a press release stating that such an inexperienced filmmaker was never been intended to complete the movie, segments of which would now be allotted to different well-known directors. In the end, McGrath was credited jointly with John Huston, Ken Hughes, Robert Parrish and my old friend Val Guest:

“Charlie (Feldman) called me in right at the beginning, and he said, ‘Look, I’m going to give you six scripts of Casino Royale and I want you to try and get one out of them all!’ and they were as widely varied as you could possibly get. There was one by Ben Hecht, there was one by Terry Southern, one by Dory Schary, and so on. All top writers, but eventually we didn’t use any of them. It was a psychedelic nightmare – he had to start shooting on a certain date because he’d signed Sellers up to start then and he didn’t want to lose him. So we virtually started shooting without a script. Then Charlie flew Woody Allen over and I worked with Woody on the script for a long time, which was great – he’s fun to work with – but Charlie would go through the stuff we’d beaten out and would cut all the gags and just leave the build-ups.”

“The main problem was that we were shooting in three different studios and we used to commute from MGM to Elstree to Pinewood to Shepparton. We had standing sets in each studio. It was a nightmare because Charlie would call me up in the middle of the night and say, ‘Look, I can get Bardot next Wednesday. Which set are we on then? Well, write her in!’ That was the way he got those eighteen or so international stars in the film. He started off by conning Sellers into doing it by saying Niven was going to do it, then he called Niven and said Sellers is going to do it and so then he got Niven. I used to sit in Charlie’s office while he conned people on the telephone. He got Bill Holden because he used to be his agent at one time, but I remember we had a terrible time getting Jean-Paul Belmondo. We told Ursula Andress, ‘You’ve got to persuade Belmondo to come in,’ and she said, ‘He doesn’t want to know about it!’ But we made her keep pestering him until he gave in. It was all a nightmare but it eventually made money – a lot of money.”

No number of cooks could spoil a broth that was already rancid, and they could scarcely improve matters. Despite the brilliant soundtrack composed by Burt Bacharach and Herb Alpert and beautiful cinematography from Nicolas Roeg, the movie was declared a fiasco, and rarely have so many negative superlatives been brought to bear on a single production, which induced Charles Feldman’s death by embarrassment just a few months after the film’s release. I’ll leave you to ponder that puzzlement, but not before thanking certain sources for their vital assistance in my research: NME Magazine and Monthly Film Bulletin Magazine. I look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to freeze the blood in your veins with more sickening horror to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl in yet another fear-filled fang-fest for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews