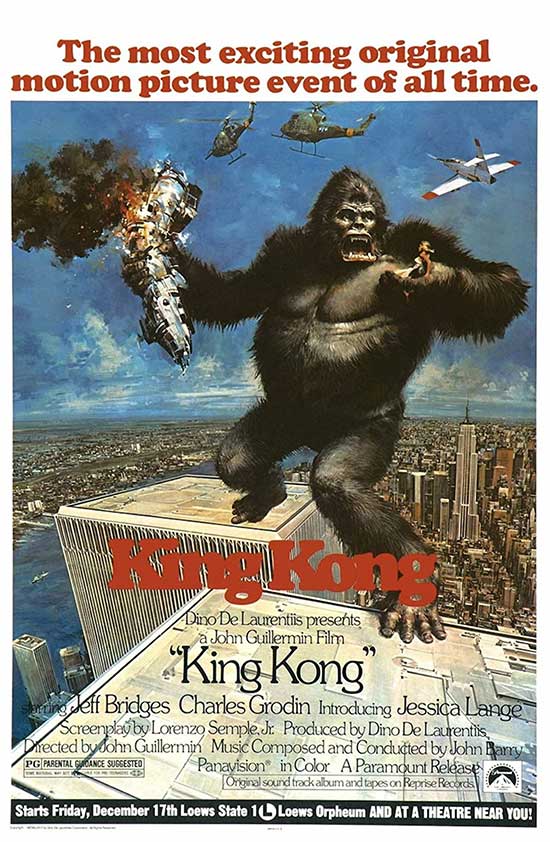

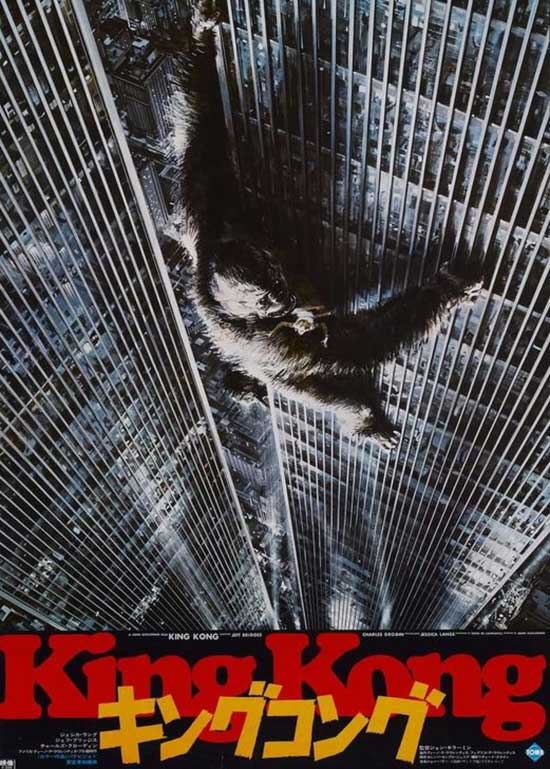

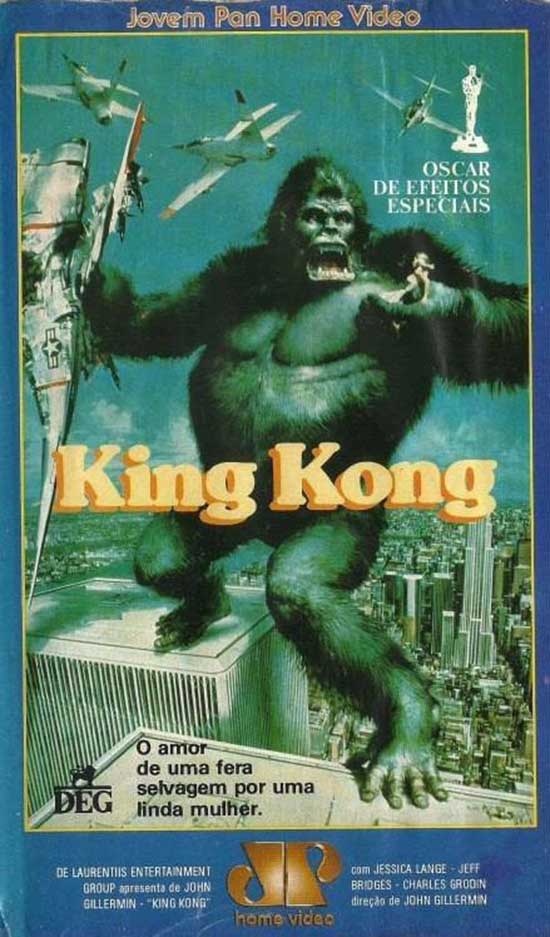

The 1976 King King remake often receives harsh criticism, some deserved. Undeniably, the creative team succeeded in delivering an often revisited cult film. Producer Dino De Laurentiis, director John Guillermin, and screenwriter Lorenzo Semple, Jr. delivered a fine reimagining of the 1933 classic, a film that captivated audiences as the holiday movie release of the bicentennial year.

The Me Decade’s version of King Kong gets hammered for being a “flop,” even though it made tons of money, and flack for being a “turkey,” another somewhat unfair assessment. No, King Kong (1976) never intended to be better than King Kong (1933), as producer De Laurentiis wanted to focus on making a fun, enjoyable popcorn movie.

The ape suit opus gets a little disjointed at times since the film’s tone shifts from serious-cum-scary to campy, over-the-top humor. The camp elements seem to be what critics despise, and understandable so.

The uneven nature tries to balance the original’s dramatic style with a modern (1970s) silliness. It doesn’t always work, but the approach doesn’t always fail, either.

Rewatching the recent Shout! Factory Blu-ray release provides another opportunity to relive a time when “event movies” were rare. Today, multiple hyped, $200 million theatrical spectacles hit screens every couple of months. That was not the case 45 years ago. When a massively budgeted, heavily marketed film hit theaters, the arrival was special. However, not every attempt was a hit, as Irwin Allen’s The Swarm (1978) proved.

Bombastic feature film events weren’t only for movie theaters and drive-ins, either. The Blu-ray presents the three-hour extended cut. NBC reportedly paid mega-million for the rights, and the extra 45 minutes needed to turn the two-hour film into a two-parter with lots of commercials never detracts from the film.

Whether watching the two-hour theatrical cut or the three-hour television version, polarized opinions might not change. For some, the campy elements don’t work and sink the film. Others enjoy the movie, especially many Generation X-ers who remember the original release.

The criticism levied at the film has validity, though. Maybe it is time to take another look at why the film had “tonal troubles.” Doing so starts with a look at the history preceding the remake.

From Skull Island to New York City to Syndicated Television

Much had changed since the original King King debuted in New York City on March 2, 1933, and the remake’s December 17, 1976 opening. You could point to the March 5, 1956, debut of RKO’s King Kong on broadcast television as the catalyst. King Kong would become a television staple for the next 20 years. Had former Disney CEO Michael Eisner, then an ABC executive, not seen the RKO film on television in 1974, he wouldn’t have gotten the idea for a remake, setting the reboot cinematic adventure into motion.

Culturally, the world changed between 1933 and 1956, and further changes occurred from 1956 to 1976. Among those changes was audience perceptions of “The Eighth Wonder of the World.” The ferocious beast who slaughtered sailors and terrified Fay Wray became a good guy.

One element that made the original film effective was Kong’s frightening, animalistic behavior. King Kong did not back down from challenges, and he had no problem killing humans who ventured into his lair. Fay Wray’s Ann Darrow knew she had no long-term chance of survival on Skull Island, and Wray portrayed sheer terror in Kong’s presence.

King Kong remains a frightening beast, a living natural disaster from the animal kingdom. He’s a giant, ferocious ape and acts accordingly. The presentation of King Kong and Fay Wray’s realistic reactions allowed the film to work.

And then time passed and everyone took a second look at Kong. They even took third, fourth, and fifth looks, watching the film’s repeated syndicated television broadcasts for two decades.

In the audience’s eyes, Kong became a misunderstood, sympathetic, and beloved creature. How often do critics refer to Kong as a “monster” when discussing the film? The pejorative doesn’t fit.

Yes, King Kong slaughtered many sailers and kidnapped a terrified woman. Even so, no one believes it was right to take King Kong from Skull Island. After rescuing Ann Darrow, Carl Denham, Captain Englehorn, and the Venture’s crew should have made their way back to New York, leaving Kong behind.

Kidnapping King Kong, turning him into a sideshow attraction, tormenting him by abusing Ann Darrow on the stage, and otherwise displaying horrific judgment and cruelty, King Kong’s NYC rampage rests mostly on the irresponsible shoulders of the humans who brought the ape to the big city.

Audiences couldn’t help but feel sorry for King Kong. The powerful emotional punch of the conclusion, combined with a thrilling and moving viewing experience, allowed audiences to forgive Kong for his brutality during the Skull Island scenes.

Everyone loves King Kong, both the movie and the giant ape. And that created some trouble when crafting the remake’s screenplay.

Not So Simple for Semple, Jr.

Lorenzo Semple, Jr.’s screenwriting career boasts of contributions to some genuinely outstanding films. The Warren Beatty political paranoia thriller The Parallax View (1974) and the Robert Redford CIA mystery feature Three Days of the Condor (1975) revealed how Semple Jr. could mix adventure, drama, and intrigue to create a believable story in a well-paced screenplay.

Interestingly, Semple Jr. had a strong hand in crafting outrageous camp comedy when he wrote the 1960s Batman television series pilot. He also wrote the hilarious and fun 1966 feature film spinoff from the television program.

Initially, the Batman television series used camp humor to poke fun at pop culture and society. Kids might not have picked up on the in-jokes when first watching the episodes, but adult viewings could reveal how brilliant the writing was. At least during the first season, the teleplays were engagingly humorous. Lazy writing and unmotivated camp humor dragged things down.

The red-hot screenwriter seemed like the perfect choice, considering the new King Kong needed to mix thrilling high adventure and scares with lighthearted humor. Overall, Semple Jr. did an excellent job regarding the scares, drama, light humor, and high adventure. Unfortunately, he went too far in the direction of camp humor in some sequences. The resultant dialogue led to laughter of the unintentional kind. The campy elements also provide critics with more than enough ample fire for bad reviews and outright condemnations.

Dwan of the Dread Dialogue

The film’s setup effectively establishes an adventure with ominous overtones. Audiences already know the tale of King Kong, so no mystery exists about what the cast will discover. Semple’s decision to make Charles Grodin’s Fred S. Wilson character an amoral oil executive drive the story and play the antagonist leaves audiences guessing about the particulars of how the proceedings play out.

Wilson remains in conflict with the more sensible paleontologist, Jeff Bridges Jack Prescott character, a “hippie” intended to connect with younger audience members and sensible enough to connect with older ones.

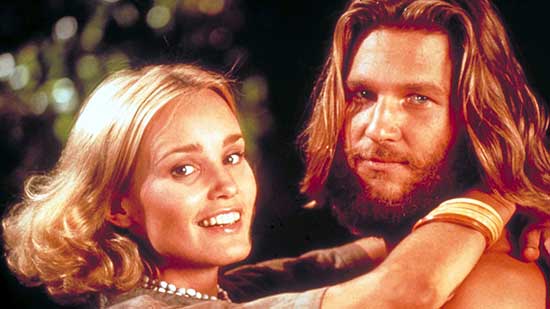

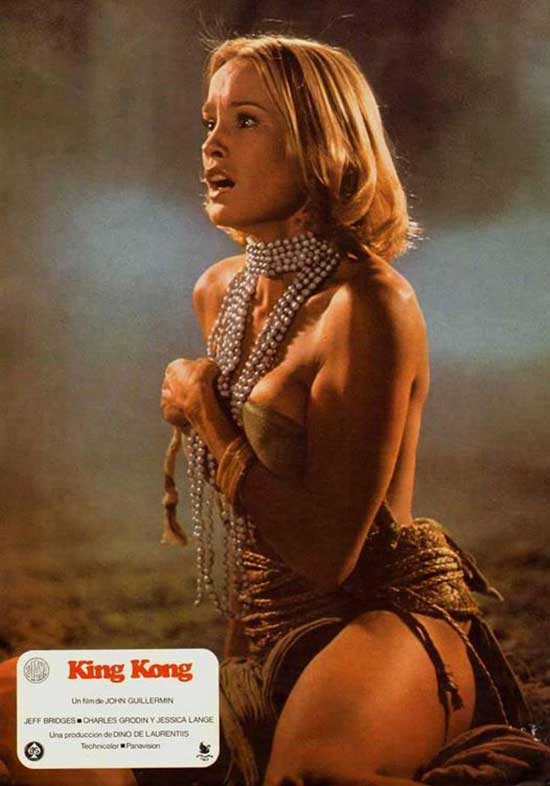

Jessica Lang’s Dwan starts as a confused, naive model aspiring to become an actress, only to shift to a reluctant celebrity who sympathizes with the tragic Kong. Dwan’s sympathies towards Kong mimic the audience’s, and audiences feel bad for Kong and his plight.

And then there’s King Kong, himself. Semple Jr.’s screenplay captures the feel of the original film, where Kong’s initial appearance evokes more horror than sympathy, and the legendary ape won’t tolerate trespassers on his island.

Everything works quite well until Kong and Dwan find themselves alone, and their personal time creates the perfect opportunity for some lousy dialogue.

As evidenced by his previous filmography, Semple Jr. understood drama and thrills. The writer had a fun side, and he had a knack for camp humor, as Batman. Switching Robert Redford with Adam West in full caped crusader costume and dropping Batman and his campy dialogue into The Days of the Condor doesn’t give you the best of both cinematic styles. It would create a mess.

Dwan’s reference to Kong as a “God damn chauvinist pig ape” might be forgivable as a throwaway line, but Semple Jr. follows up the exchange with the formerly terrified captive noting, “I’m a libre,” and then asking Kong, “What sign are you?” Later in the film, when Kong grows angry at being trapped in the ship’s hull, Dwan tries to calm him down and asks, “Remember me from before, your blind date?”

What did Semple Jr. think when he came up with these goofy lines?

Likely, he wanted to de-emphasize the “monster side” of King Kong and make him a more tragic figure. Giving Dwan lighthearted dialogue established that she didn’t see him as a threat, and neither should the audience. A little comic relief doesn’t hurt when trying to take the edge off the forthcoming tragedy.

King Kong finds himself in an impossible situation and adding some humor to the exchange between him, and Dwan keeps Kong in “good guy” territory. Audience anger remains directed at Wilson and the Petrox Company because they’re the reason for King Kong’s rampage in New York.

Still, the dialogue is too campy, over the top, and out of place to work.

Wrong Approaches at the Right Time

Films are collaborative efforts, and the blame goes around. Producer Laurentiis and director Guillermin didn’t make demands that Semple Jr. revise the sillier dialogue. Nor did they bring in a script doctor to fix things. Paramount executives green-lighted the release.

Critics both then and today harp on the campy elements, noting how weak dialogue drags down the film. Maybe “distracting” is a better description than “drag.” King Kong (1976) isn’t a bad film, but the out-of-place campy elements hurt the film. Amazingly, Semple Jr. would repeat the same mistake in 1980 with Flash Gordon

Audiences would be less forgiving in 1980 than they would be in 1976. The 1970s represented an era of gaudiness, and silliness often reigned supreme during the period. The decade had its somber moments, and films such as Looking for Mr. Good Bar might more realistically define it. However, the era loved its silly side. Maybe a mix of seriousness and silliness fits the 1970s perfectly.

And King Kong (1976), for right and wrong, shows how to mix the serious with the silly.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews