Koji Shiraishi is name undoubtedly known to most fans of Japanese horror. Over the past two decades he has dabbled in numerous forms of the genre, from ghosts to zombies and from urban legends to gore-porn, all with varying rate of success. However, the sub-genre that Shiraishi has truly mastered in a way that is hard to find comparison for, is mockumentary horror. Within it you can find not only the most solid and successful pieces of his work, but also the most unnerving ones. Shiraishi has not merely utilised the same tired genre tropes saturating the mockumentary/found-footage genre since The Blair Witch Project, but instead built an entirely original mythology, around which he has weaved his stories. In the centre of his works are four core films; Noroi (2005), Occult (Okaruto, 2009), Cult (Karuto, 2013,) and A Record of Sweet Murder (Aru yasashiki satsujinsha no kiroku, 2014), all of which seem to operate inside the same fictional universe and share the same root of terror.

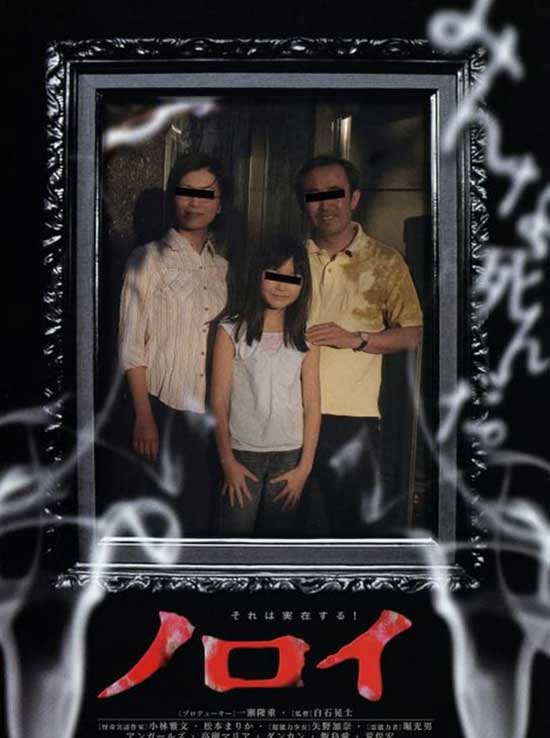

To start examining Shiraishi’s mockumentary catalogue, there is no better place to start than his 2005 masterpiece Noroi. It tells a tale of documentary filmmaker/ghosthunter Masafumi Kobayashi (Jin Muraki), who stumbles on a deadly set of events while investigating a series of seemingly separate paranormal events: a woman complaining about weird noises coming from next door, a child psychic Kana Yano’s (Rio Kanno) awe-inspiring performance in a TV variety show, the actress Marika Matsumoto’s (playing herself) TV appearance using her psychic powers, and a local mad man and super psychic Mitsuo Hori (Satoru Jitsunashi) being interviewed about “ectoplasmic worms”. After some serious investigating, Kobayashi finds the connection between the bizarre incidents to be an ancient deity called Kagutaba. Even worse, it seems that anyone who comes even close to its destructive trajectory is in grave danger indeed. Together with Hori and Matsumoto, Kobayashi needs to get to the bottom of the mystery before he and everyone else involved fall victim to Kagutaba’s hateful curse.

In the world of mockumentary horror, Noroi is in a class of its own and I can only think of a handful of films that compare to the brilliant way that Shiraishi has managed to weave this tale of supernatural suspense. Much of its power comes from the way the film is constructed from combination of handheld documentary style footage, TV-clips, interviews and news inserts. It gives the story a sense of realism that elevates it above the bog-standard mockumentary/found footage affair. If you would happen upon Noroi just by chance, without knowing anything about it, the chances are you would at first think it to be a genuine documentary. Shiraishi takes his time building the different story elements, slowly revealing their connection to each other and amping up the suspense in such a gentle manner that you barely notice it until you find yourself sitting on the edge of your seat in anticipation. Special effects used are subtle and few and far between, giving the intricately built atmosphere chance to shine as the main source of terror. It is absolutely mockumentary horror at its best.

The cosmic themes of Noroi are not quite as blatant as in some of the films that would follow. The focus is heavily on Kagutaba and its curse, and the film could easily be categorized under the sub heading of demonic or black magic horror. However, when examined in the context of the three subsequent films, the hints towards greater, cosmic powers will start to reveal themselves.

Shiraishi’s next excursion into the world of mockumentary horror came four years later in a form of his 2009 film Occult. This time the cosmic horror came through loud and clear and the concepts that were hinted at in Noroi, were fully realised. The format of the film is very similar to its predecessor, with a documentary crew trying to entangle a bizarre, potentially supernatural mystery behind seemingly random stabbings in a popular tourist destination. The closer they get to the only surviving victim of the attack, more convinced they are that there is more to these events than meets the eye, and as is the case with Kobayashi in Noroi, they too find themselves in a middle of strange and dangerous circumstances.

Occult takes a step further towards mixing fiction with reality by scrapping the idea of using a fictional character in its centre and rather having Shiraishi play a version of himself as the man behind the camera. Also playing himself is assistant director Shinobu Kuribayashi, the actor Shôhei Eno (as the surviving victim of the horrendous knife attack), as well as the legendary horror director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who makes a delightful little cameo in the middle of the film. While none of them are a really playing themselves but merely a version of, this little decision does go a long way in bringing a real sense of authenticity to the film. The interactions between the characters are natural and believable, in parts to a point of uncomfortable awkwardness. A scene where the crew first encounters the more unhinged side of Eno, is likely to make most people cringe with discomfort. It is a beautifully played out interaction, familiar to anyone who has ever had to deal with random drunk person who wonders to your bar table and manages to insult everyone present by simply being themselves. It’s cringeworthy, yet intimidating, perfectly balanced somewhere between annoyingly harmless and a truly dangerous.

Much like Noroi, Occult does not rely on flashy special effects and keeps any encounters with the supernatural as small glimpses on a grainy video. One could criticise the film for the rather low quality of some of these effects, or for not being particularly scary, but that would go slightly beside the point. The horror in the film does not stem from the effects, but from the atmosphere that Shiraishi has once again so beautifully build. The supernatural elements seep into the story gently, making you question whether they really exist or are they merely figments of Eno and Shiraish’s shared psychosis. At the same time, the overwhelming nature of these forces is as frightening as the curse in Noroi; the people destined to be in the midst of them have no choice in the matter but are stuck on their inevitable road to doom. This sense of cosmic, looming dread is balanced with horrors more rooted in real life. The two seemingly random acts of extreme violence featured in the film are something that could, and have happened in real-life, and as such bring another layer of very real and very relatable terror to the story.

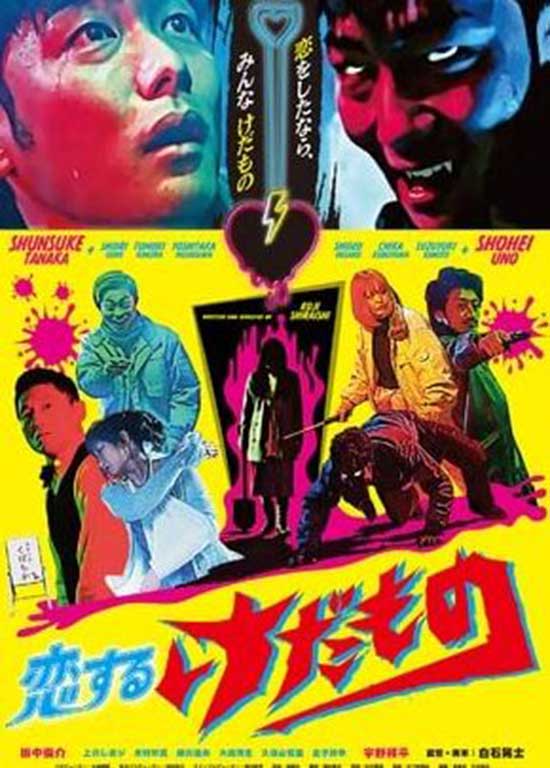

In 2013 Shiraishi once again returned to the mockumentary format with his film Cult (Karuto), this time tackling the supernatural forces in a very direct manner. Three idols Yû Abiru, Mari Iriki and Mayuko Iwasa (playing themselves) are recruited to participate in a TV program documenting an exorcism ritual being performed in a house of a local family. Their lives are plagued by strange noises as well as bizarre apparitions and help of a spiritualist priest Unsui (Shigehiro Yamaguchi) is needed in order to rid themselves of these pains. Things get complicated when the exorcism does not go according to plan and Unsui ends up in a hospital. Into his shoes steps in a young, too-cool-for-school, exorcist Neo (Ryosuke Miura), who in his own cocky manner does his best to help the Kaneda family in getting rid of the spirits haunting them.

Cult seems to operate in the same realm as Noroi and Occult before it, but Shiraishi’s approach to this particular story is definitely much more straight forward. The supernatural events start from the very beginning and continue in a steady stream throughout the film. The effects used are again similar to Noroi and Occult, with twisted apparitions and phantom worms from other dimensions, but they play a much bigger part than in the previous films. This unfortunately does not necessarily work for the films benefit as these effects work best when only featured as a side note rather than the main event, and as such some of them do indeed affect the film’s scare potential in harmful way. With the element of supernatural being prominently present from the beginning, the film does not quite have the same chance to build suspense in the same way as its predecessors, and Cult definitely lacks the ominous atmosphere that Shiraishi has previously been able to create.

Cult was released as part of a horror trilogy including Eisuke Naitô’s The Crone (Kôsoku bâba) and Norio Tsuruta’s Talk to the Dead (Tôku tu za deddo). The three films, all released in quick succession, bear no relation to each other story wise or thematically, but are a trilogy in name only; the kind that that are cobbled together (I’m guessing) to simply boost the profile of the films involved by linking different horror directors works together. Whether being part of this project influenced the way Shirashi developed the screenplay for Cult, I do not know, but the very uncomplicated, fast paced manner that the story unfolds does feel somewhat removed from the intricately woven mysteries of Noroi and Occult. The end of the film does offer a typically Shiraishi like twist to the story, but it’s not quite enough to save it from the otherwise lacking execution.

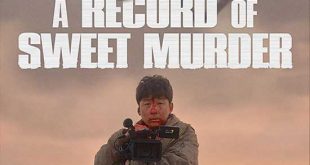

Shiraishi’s next jaunt in the mockumentary world again changed his take on the genre, whilst still keeping the story in the same universe. The 2014 Japanese-Korean co-production A Record of a Sweet Murder dives into the mind of a deranged serial killer, who is convinced that his urge to kill comes from direct orders from god. Having gone on a killing spree and now in hiding, Sangjoon (Je-wook Yeon) invites his childhood friend and a journalist Soyeon (Kkobbi Kim) and a Japanese cameraman Tashiro (Shiraishi himself) to come and meet him in an abandoned apartment building. Little do they know that Sangjoon has not only invited them in for a simple interview, but to witness him murder the last two people of the unlucky 27 God has told him to kill. If he manages to follow God’s instructions, not only will his dead childhood friend return to life, but all the 27 of his victims will also be gloriously resurrected.

While the underlaying themes of the film are definitely in the same ballpark as Shiraishi’s earlier mockumentary pieces, A Record of Sweet Murder goes in completely different direction with pretty much everything else. While Noroi and Occult both offer quite complex story arcs, stretching over a length of time and various locations, A Record of Sweet Murder essentially takes place in one room, within just few hours period. It is extravagantly violent and much of the films running time is actually focused on someone or other getting beaten, stabbed or raped; a far cry from the slow-paced world of Noroi. However, slowly the same otherworldly elements will start to filter into the story and the end of the film will once again reveal that we are indeed dealing with the exact same forces as before.

Shiraishi has opted to examine the cosmic themes through the lens of mental health issues. Starting from the characters of Mitsuo Hori and Junko Ishii in Noroi, mentally unbalanced characters as conduits for otherworldly messages is something that is repeated in all the stories (except perhaps for Cult). As is the case with Mr. Hori and Ms. Ishii, they are not always necessarily in the centre of the story, but nevertheless always play a key role in unfolding the mysteries within it. If measured purely on screen-time, Junko Ishii plays relatively minor part in the events of Noroi, but as far as the story goes, she is an integral part of the whole terrifying ordeal. Just like Eno and Sangjoon after her, Ishii claims to be hearing the voice of “God” and these messages from the divine take her down a gruesome path or kidnap, black magic and murder.

While Ishii mostly kills indirectly (her mere presence seems to be dangerous to those around her), Eno and Sangjoon both present a much more corporeal threat to people around them. Eno in particular seems much more interested in his own mission than anything else. The fact that the ritual he has been destined to perform is going to cost the lives of countless others, does not bother him, but he follows the same doctrine as any religiously motivated suicide bomber would: sacrificing himself in order to get to paradise. Even Sangjoon, perhaps the most violent and dangerous of them all, feels remorse for his actions. He does not want to be killing people, but the voices in his head have convinced him that if he simply finishes the task they have set him, they will not only grant him his greatest wish (the return of his beloved friend) but also the save return of those he has killed. Eno on the other hand revels in the role he has been given and time and time again shows a complete lack of empathy towards anyone around him, suggesting he might not have been a very stable person to begin with. The only exception to the rule is Mitsuo Hori, who, while intimidating, only wants to help Kana and others in the middle of Kagutaba’s terrifying orbit, and rather than conversing with any divine powers, believes to be receiving messages from space.

Indeed, the aftermath of these cosmic events is quite different for all the characters. Sangjoon gets what he has been promised and the murderous rampage he has find himself on, has a happy ending for all. Meanwhile Eno’s ritual also has the result he hoped for, but instead of paradise, he gets a psychedelic, Obayashiesque hellscape where he and his disembodied victims will float for all eternity. Junko Ishii and Mitsuo Hori both end up dead in mysterious circumstances: Hori killed by someone or something, and Junko assumably, but not necessarily, by her own hand. Whatever the case, both deaths are deeply intwined with Kagutaba and his entrance to this world.

It is unclear whether these unrelated characters are all receiving their messages from the same source. If the “God” that Ishii, Eno and Sangjoon all talk about is the same deity, why does it treat its mediums so differently? Some are killed, yet others get their deepest wishes fulfilled, making it almost seem like the forces at play are merely toying with their subjects. Or perhaps the world is surrounded by a whole hoard of ancient beings, just ready to pounce on those who are receptive to their message? Who knows. One thing is for certain though: our feeble human minds are not equipped for such encounters and only madness lies ahead for those who dare to try.

Examining the similarities between the thematic content as well as the visual language, it certainly seems like the four films share a common source of terror. Runic symbols, psychic messages and ectoplasmic worms from other dimensions are all featured in Noroi and repeat throughout the four films. Is the curse released on the world by Junko Ishii the same one that haunts Eno, Sangjoon, and even the Kaneda family in Cult? In Noroi, Kagutaba is described as a “tool of destruction”; something that will perform evil deeds and sow chaos in its wake if left to its own devices. Can all these terrifying cosmic events emanate from the same corrosive power, now finding its way the modern world and infecting people in a similar manner to Sadako’s cursed video tape? After burning its way through Ishii, Hori and Kobayashi, did it simply move on and finds it new victim in the unbalanced mind of Eno? Or is Kagutaba too just another cog in a much bigger machine of infinite cosmic terror?

Whatever the case, Shiraishi has managed to tap into the core essence of cosmic horror of leaving much of the story to the viewers imagination, doing it in a way that not only leaves one questioning, but also filled with a sense of ominous dread. He has created a completely original mythology that links the present with the past, reality with fiction, and all of us with forces so terrifying we can barely comprehend them. I for one surely hope that we have not seen the last of Mr. Shiraishi’s cosmic works, but the years ahead will bring us more tales of terrifying otherworldly encounters.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews