Horror movies present intriguing hypothetical avenues for critical analysis. Whether an escapist or gritty film, audiences can look for themes within the subtext driving the story. Unless, of course, we are dealing with entirely disposable entertainment. The horror movie genre often roots itself in pure exploitation, with a distribution company-driven product designed to make fast money. Exploitation roots, however, don’t automatically disqualify a film from a deeper analysis.

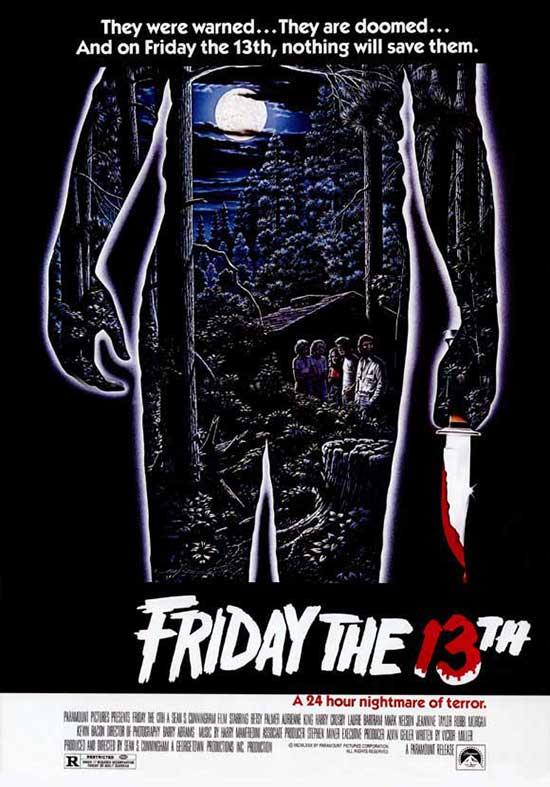

Friday the 13th (1980) will never rank high on anyone’s list of complex works of dark fantasy. It’s an exploitation film, true, but not heavily exploitive. Untold numbers of violent horror films were far worse. Exploitation in the form of stalk-and-slash mayhem drives the film, and, upon looking a little closer, you’ll see touches of artistic merit. Friday the 13’s recurring motif of falling rain underscores impending horror and adds a subtle metaphor to the carnage.

A Slash Across the Drive-In Screen

Artistry didn’t drive Friday the 13th to mega-hit status. Marketing and timing brought the film to massive box office returns.

Friday the 13th benefited from an excellent trailer and accompanying television spots that hyped the movie. The drive-in circuit was still three years or so away from experiencing the onset of a substantial decline, and Sean Cunningham’s slasher film capitalized on the coattails of Halloween. Since no Halloween sequel saw a release until 1981, fans clamoring for more jumped on Friday the 13’s low-budget and marginally similar mysterious killer-on-the-loose cinematic train.

Friday the 13th, after being sold Paramount, a studio that would never likely have touched the film had Halloween not been such a big success, skyrocketed to $40 million in ticket sales in the United States. The film spawned the massive slasher movie craze that lasted roughly two years. While many of the movies were worthless, many indie filmmakers did produce some excellent ones, features far superior to Friday the 13th and its sequels. 1981 saw the release of four exceptional slasher films that rose above the pedestrian maniac-with-a-knife format: The Prowler, My Bloody Valentine, Graduation Day, and Night School. Friday the 13th was the franchise hit and the “real winner” of the slasher film cycle. The series outlived the death of the slasher film by years and years.

While not a die-hard horror film fan critical favorite, it would be unfair to say Friday the 13th’s made no attempts at artistic merit.

Narratively, Friday the 13th hooks audiences with a very creepy opening prologue and frays their nerves with a hair-raising final 20 minutes. Unfortunately, the middle of the film consists of much meandering until the thrilling climax. The notorious setting of the film, Camp Crystal Lake, does slyly add suspense, albeit in the background. The counselors find themselves trapped in pure isolation, making escape difficult. The lonely rural scenario lulls the characters into thinking they are safe. They’re not. The rustic environment dulls their senses of awareness while they await doom.

Or, is there a warning present? At the deceptively serene lakefront world, the natural world provides them with a jarring warning of danger to come in the form of rain.

The Shower Dream

Screenwriter Victor Miller wrote an intriguing scene that deserves more attention than Friday fans and historians appear to give it. The scene has Marcie (Jeannine Taylor) talk to Jack (Kevin Bacon) about a strange recurring dream she experiences. The dream makes little sense to her, as it strangely borders on a nightmare.

“Oh, it’s gonna storm.” So quips Jack to Marcie. Jack’s more ominously prophetic than he realizes. And Marcie inadvertently joins him when she reveals her frequent dream about a heavy rain falling during a thunderstorm. The sound of the crashing rain causes Marcie to cover her ears, but the sound only becomes louder. The rain continues until it turns into blood, pooling into small rivers and washes away as the noise stops.

MARCIE

I call it my shower dream.

JACK

But this is no dream.

To borrow a line from Phantasm II‘s TV spots, “No, it’s not.” Blood will flow in puddles as impending doom will soon arrive. The mystery of the imminent doom no longer exists after 40 years, as millions upon millions of people had already seen Friday The 13th. Back in 1980, audiences watching the film for the first time did not know that Pamela Voorhees will soon cause blood to flow due to her rampage.

And rain is an appropriate metaphor for trouble-bringing rain.

Destructive Rains and Reigns

Pamela’s reign of terror is not unlike the rain that falls in the woods. Destructive yes, but not entirely unnatural. Rain can be harmful when too much of it falls. Roads can flood, rivers may overflow, bacteria travels through water, and so on. All these issues become threats found within the natural order of rainwater.

Rage drives Pamela’s murderous rampage. Rage can be normal and, like rain, come with varying degrees of harm. The root of her rage, the drowning of her son, explains her anger. If Jason died due to negligence, Pamela garners justification for rage and bitterness. While unhealthy, resentment becomes a natural reaction based on the circumstances. An average person would feel the same way given the loss, but Pamela is far more abnormal than normal. She allows her rage and resentment to consume her and drive her to the mental breaking point where she becomes a homicidal maniac. Her murderous rampage directs itself against people who have nothing whatsoever to do with the inciting incident. They’re simply people caught up in the storm.

Expressions of anger, when controlled, could have a positive affect. Working out aggression by playing handball reflects a common strategy people use to deal with pent up frustration. And playing handball has health-improving benefits. Similarly, even hard rainfall brings with it many positives. Without rain, the ecosystem would collapse. Too much rain, however, in the ecosystem suffers dramatically. Likewise, violent expressions of anger and rage create devastation upon spiraling out of control. Pamela Voorhees is a rainfall that turns into a hurricane of mindless devastation.

Rains Falls and Warnings Land Unheeded

In the film, rain appears in ways that extend beyond pure symbolism. The actual use of rain in several scenes does an excellent job of heightening the tension by creating a sense of foreboding. At earlier points, the cinematography captures the sufficiently bright and green natural world of the New Jersey forest where Camp Crystal Lake resides.

At times, the camera lingers on the forest and eliminates all sounds except for natural ones. Long shots of forestry accompanied by the sounds of birds chirping might seem somewhat clichéd, but it works on a few subliminal levels. The camp appears calming. Becoming too calm with the location leads the counselors to dismiss the potential of any danger.

As the second act comes to a close, rain begins to fall on Camp Crystal Lake. If there were ever two reasons why the characters should stick together and stay inside the cabins, it would be the combination of harsh rain and the dark of night. Every character didn’t hear the earlier warnings and the rain’s blood puddles, but the danger of what the rain brings still exists.

The rain is not a danger. The rain is the warning of danger. Leaving the cabins, going off alone, ignoring the perils of the surrounding environment, these are all examples of ignoring the warnings. Eventually, the rain does stop, but this doesn’t mean anyone’s out of danger. Rather, the end of the rainfall Makes it easier for Pamela Voorhees to make her debut. The rain doesn’t turn in the blood, but it’s disappearance reveals the person who is the cause of the crimson flow.

A Life (and Many Deaths) in the Woods

The rain has a cleansing effect in the cities, one that Pamela Vorhees wishes to mimic. Rain sweeps city dirt and debris from sidewalks and down the drain. She wants to clean away the corrupting influence of city dwellers from the forest by removing the “camp” from Camp Crystal Lake. She sees the counselors as a collective perversion and an uncaring one at that. As the rain sweeps away dirt, Pamela Voorhes wants to sweep away the corrupting element the camp counselors bring. Consider this a homicidal spin on Henry David Thoreau’s musings in Walden.

In Thoreau’s words, “We need the tonic of wildness…we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature.” And the counselors aren’t the only ones who should avoid exploring the woods. Had Pamela and Jason stayed out of it, Jason would still be alive. Maybe that is the true root of her rage: self-loathing. Perhaps killing the counselors allows Pamela to kill her internal guilt externally, or at least try.

The Rain and Reign Stop

After the rain stops, Pamela Vorhees reveals herself to Alice. Stepping out of the rain and the forest’s shadows not only reveal Pamela’s menace, doing so exposes her vulnerability. The killer can only use the natural world to hide for so long. The rain does stop, and there are puddles of blood — Pamela’s. Both the rain and reign of terror come to an end.

At least the ones with Pamela.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews