Long-time fans of horror films likely can’t shake the shock from seeing “cannibal zombie entertainment” find mainstream acceptance. Decades ago, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead pulled in well over $5 million during its original 1968 theatrical run, yet few production companies took a change releasing an equally violent copycat. It wasn’t until 1974 that a creepy film that “borrowed” some elements of NOTLD finally appeared, and it did so with a unique sense of style.

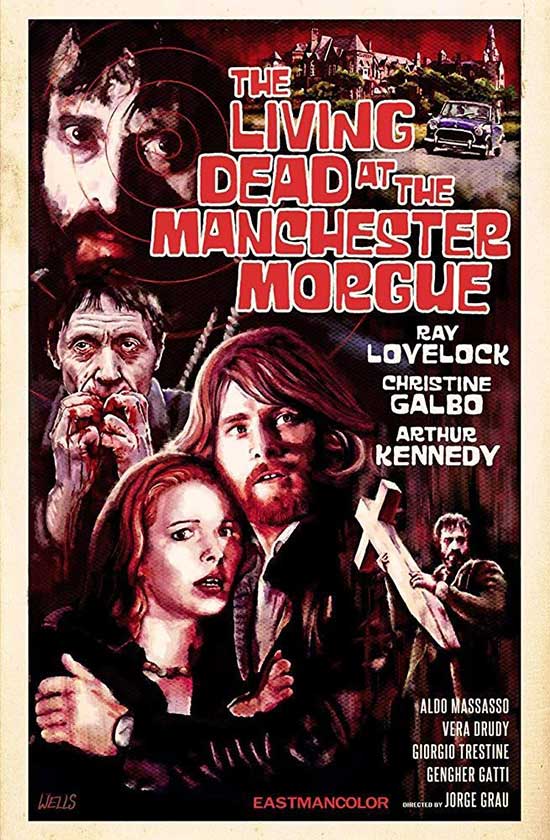

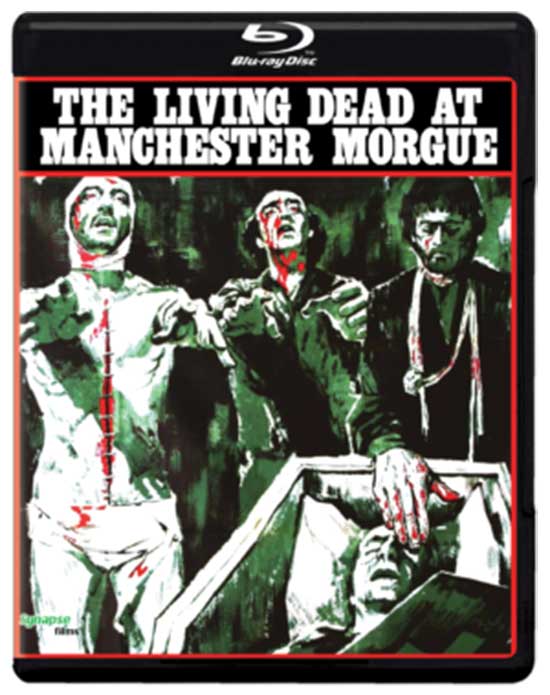

Jorge Grau’s The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue, aka Breakfast at Manchester Morgue and Let Sleeping Corpses Lie, found itself, unfortunately, dumped on the U.S drive-in circuit as Don’t Open the Window in an edited version. The Spanish-Italian chiller did manage to grow a cult following over the years. A new uncut 4K release by Synapse Films may draw new fans this early Romero-esque zombie film. Grau crafted a suspenseful and chilling feature that captivates audiences with a fast pace, great soundtrack, and unusual subtexts and themes for a horror shocker. While impossible to miss the overt environmentalism themes, a careful look uncovers themes drawing from the Cool Hand Luke concept of “failure to communicate.”

In the classic Paul Newman film, the rebellious title character runs afoul of prison rules because he won’t listen. He has to do things his way and suffers because of it. The cast of human characters in The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue suffers from a collective failure to communicate, and dire consequences result.

How Did the Dead Become the Living?

The basic plot is simple: A young, hipster art dealer named George (Ray Lovelock) finds his trip to a country home sidetracked when a careless driver, Edna (Cristina Galbó) wrecks his motorcycle. Despite their awkward first meeting, she convinces him to go to a different town, where her sick sister rests infirmed at the local hospital. Upon arriving, strange things begin to happen as a recently drowned hobo comes back to life and, in a scene riffed from NOLTD’s first zombie appearance, tries to attack Edna in her car. No one believes Edna’s story about the vagrant because he is assuredly dead, except that he’s not.

The homeless man isn’t the only walking corpse, either. A strange machine designed to kill insects, or, rather, causes insects to kill one another, brings the dead back to life. And the dead are hungry.

Slowly, an incredulous George figures everything out, but the police won’t listen to him. He can’t convince anyone flesh-eating monsters are on the prowl, and the authorities, especially the jaded Inspector (Arthur Kennedy), blame him for all the dead bodies piling up. Can George save Edna, now trapped at the hospital, where the sleeping corpses from the morgue now begin to rise?

Everyone Hears, But No One Listens

The humans in this film tend to argue with one another a lot.

Everyone finds themselves in a terrible bind because they won’t hear each other out. The characters find themselves bickering with one another and unable to communicate due to their differences: age, class, gender, profession, and so on. The lack of communication leads to ignoring a growing problem: the dead are rising from their graves to feast on the living.

The police, understandably, have no desire to listen to strange tales of the dead. However, we do get the impression that Arthur Kennedy’s absurdly dry Inspector character wouldn’t listen to George under any circumstances. He’s not a fan of “dirty hippie-types.”

And no, the exterminator crew won’t listen when informed their bug-killing machines are raising the dead. If the exterminators would follow George’s advice and shut off the bizarre insect-killing/living dead-making radiation machine, at least the zombie population could somewhat stop growing.

Humans lock themselves into their Own Private Idaho communication boxes, allowing the dead to make their moves.

The Hero Needs an Attitude Adjustment

Our hero doesn’t deserve all our sympathy, though.

Of course, George’s story is a bit too fantastic to swallow. However, we get the impression that no one would listen to him regardless of what story he told. The working-class police and exterminators don’t like George because of who he is and what he represents. No story he tells would be acceptable, and he’s dismissed.

George does himself no favors, however, by making himself unlikeable to people whose help he needs. George can’t hide the fact he despises authorities. His dripping contempt and “I guess I have to talk to the police attitude” doesn’t endear him.

George’s arrogance is what dooms his fate. Rather than accept he is in the impossible situation of trying to prove the impossible, he feels all he has to do is say something, and people will listen. After all, he’s the superior and they are inferior. He doesn’t have to temper his tale to make it more believable. How dare they find his story incredulous.

That creates parallels to George’s environmental concerns about pollution. Saying anything from a condescending high horse does not persuade even when you may be in right and promoting beneficial things to those ignoring you. Regardless, how are you say something and how you act factor into people’s reactions. George’s personality is one that puts up barriers. He’s so oblivious to his shortcomings, and he can’t make the obvious adjustments necessary when trying to prove to the world the dead have come back to life and are eating a living.

The Dead “Get It”

The “living dead” might as well refer to the human characters and not the zombies. Are you indeed a living and actualized being when locked into your self-generated bubble? Everyone comes off as so ultra-opinionated, they can’t interact with one another to, literally, save their lives. And what greater zombie is there than the stubborn, self-centered person who can’t see things the “other guy’s way?”

Ironically, the Living Dead can communicate with one another, which enables them to bring others back from the beyond and organize their march on the living. The dead need not communicate with the living. They just feed on them.

And they may feed with an outrageous lack of restraint.

One Step and a Shock Too Far

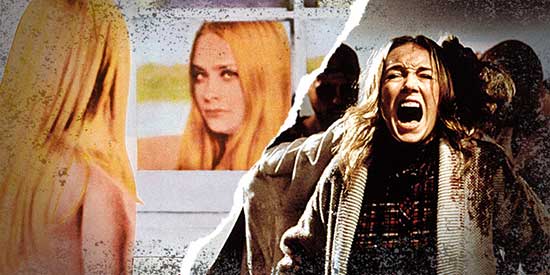

The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue allows its pace and character interactions to keep audiences glued to the screen, and, knowing its audience, the film also delivers excessive gore and shocks. The film’s most infamous attempt at shocking the 1970s era jaded grindhouse and drive-in audience involves the murder of the switchboard operator at the hospital.

George calls her to warn her about the living dead’s inevitable rise from the morgue and their intended siege, and, not surprisingly, faces utter disinterest. The switchboard operator remains engrossed in a mundane, gossipy personal phone call. So, she is entirely oblivious when a zombie sneaks up on her, attacks her from behind, disembowels her, and, in a brutal display, tears at her breast.

Even after 45 years, the death scene still shocks and not due to the crude special effects. The time-capsule viciousness of the killing is inconceivable to modern audiences.

During a recent theatrical screening to hype the film’s 4K restoration, Hollywood Blvd.’s Egyptian Theater audience set in stunned silence watching the brief-but-graphic scene play out. Since this was a revival showing, the audience comprised of horror fans who likely experienced a ton of grim movie carnage. Some, however, weren’t prepared for a shock-value killing this unrepentant and morbid. The overtones of sexual violence of the attack leave you unsettled.

The sexual violence takes things too far, and critics will, rightfully, label it as an example of unbridled 1970s era misogyny. In truth, violence towards women was far more brutal and prevalent during the days of the grindhouse and drive-in theaters. During the era, distributors and producers relied on such scenes to promote prurient word-of-mouth advertising among heavily male audiences. Shocking sequences allowed “adult’s only” horror film fare to gain infamy. A grotesque buzz could then help a horror film’s word-of-mouth marketing campaigns. Based on the above description, some readers might be moved to seek out the DVD, human nature being what it is.

Grand Guignol shock value aside, the scene maintains a perverse connectivity to director Grau’s themes. George repeatedly calls the switchboard operator to try to warn her about the impending dangers of the living dead. She pays him no heed, and her self-absorbed obliviousness prevents her escape.

While the scene intends to shock, Grau continues the notion that a failure to listen, a critical part of effective communication, has consequences. In the 1980s, immoral behavior traditionally leads to death in the slasher films. Grau’s feature promotes something more cerebral: closed-mindedness and ignorance, born of a self-centered nature, while not capital offenses, set people down the path to ruin. The thematic moralism weaves into the switchboard operator’s demise, but excessive violence muddles the message. The unsettling death does it go too far and drags the film down a path of downbeat cynicism.

Cynicism is the note Grau wishes to end the film upon.

An Era Dies And Its Corpse Lies Still

There exists a very 1970s sorrow to Living Dead at Manchester Morgue. Anyone expecting an upbeat conclusion hasn’t watched enough indie films from the era. While big-budget studio features often embraced escapism, the dark fantasy world of horror usually wrapped its arms around all things downbeat. Call it a cinematic trend born the fallout of the failed naiveté of the 1960s. Don’t think six-years-out-of-date hippie George isn’t a deliberately chosen character type.

While not a colossal hit, The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue did influence other features. The hospital setting and close-up shot of a hypodermic needle entering an arm from Halloween II (1981) and the use of the cross headstone as a weapon from City of the Living Dead (1980) reflect two similar components found in the 1974 zombie feature. As long as Jorge Grau’s The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue continues to receive re-releases, special editions, and essays about its merits, it may continue to influence for years to come.

Get the new release of The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue on blu ray per Synapse Films

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Thank you for sharing