In a 2012 interview with The News & Observer, Alice Cooper says, “Rob Zombie and I are basically best friends, because he totally gets that horror and comedy are in bed together.” Certainly, the uneasy connection between humour and revulsion informs Rob Zombie’s first two films, House of 1000 Corpses (2003) and its sequel The Devil’s Rejects (2005). However, rather than opting for straightforward comedy-horror hybridity, both films carry out a deconstructive and tonally destabilizing exploration of Americana in its bawdiest, goriest and most outrageous forms. With a musical background in ‘80s New York noise giving way to industrialized hillbilly psychedelia, Zombie established himself as part-time creative renegade, part-time purveyor of America’s darkest, famous iconography.

In a 2012 interview with The News & Observer, Alice Cooper says, “Rob Zombie and I are basically best friends, because he totally gets that horror and comedy are in bed together.” Certainly, the uneasy connection between humour and revulsion informs Rob Zombie’s first two films, House of 1000 Corpses (2003) and its sequel The Devil’s Rejects (2005). However, rather than opting for straightforward comedy-horror hybridity, both films carry out a deconstructive and tonally destabilizing exploration of Americana in its bawdiest, goriest and most outrageous forms. With a musical background in ‘80s New York noise giving way to industrialized hillbilly psychedelia, Zombie established himself as part-time creative renegade, part-time purveyor of America’s darkest, famous iconography.

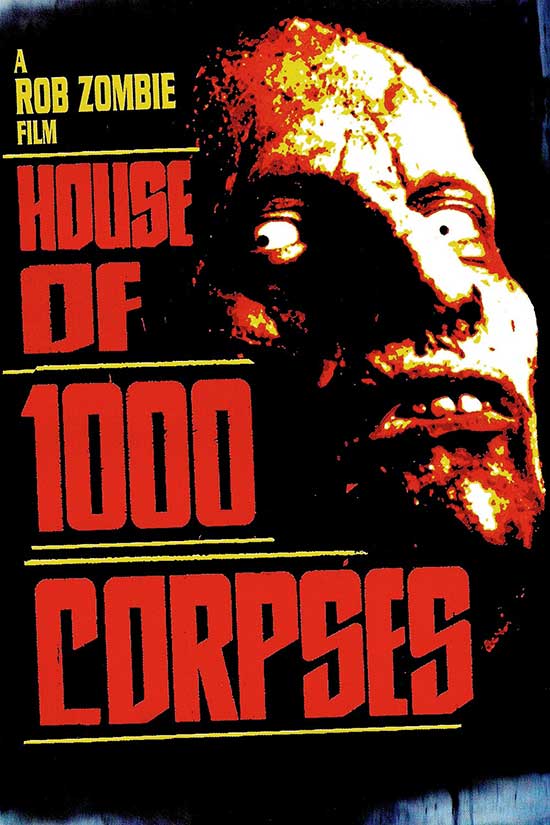

The musician’s directorial debut House of 1000 Corpses uses overt pastiche to its advantage. It draws broadly from the plot structures of Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre films, riffs on vaudeville performer/filmmaker Tod Browning’s sensibility and names its murderous Firefly family members after various Groucho Marx characters. The film moves beyond the confines of specific pop cultural references to visualize parallels between broader American traditions—vaudeville, the traveling carnival, and of course the mythology surrounding “celebrity” serial killers. House delivers its acrid vision of white Americana in a mode showcasing Zombie’s background in music video direction. Its scenes are replete with bold primary color filters, rack zooms, hyper-stylized lighting and constant slippages between various film stocks (16mm, 35mm and even occasionally videotape).

This formal bombast undergirds a bare-bones narrative. House follows a group of urban friends traveling together in hopes of finding material for a planned book on bizarre American roadside attractions. They end up stopping at clown-faced Captain Spaulding’s (Sid Haig) Museum of Monsters and Madmen; in one of the film’s most vividly disturbing sequences, Spaulding guides the would-be protagonist friends through his Museum ride, which displays gruesome animatronic dioramas devoted to America’s most infamous serial killers. Before long, the urban friends are lured to the Fireflys’ otherworldly home, which resembles an Ed Wood soundstage reimagined for an alternate-universe episode of MTV Cribs, marinated in primary-colored light and detailed with otherworldly production design. The friends are trapped and subjected to torture through a litany of means, which intensifies in both scope and theatricality as the film charges toward its climax.

House’s dramatic tension is simple, pitting visibly upper-class, white non-heroes against white “hillbilly” murderers, who want nothing to do with their visitors’ pseudo-anthropological condescension. Crucially, Zombie offers no redeeming characteristics to his victims but graces the Firefly killers with burlesque charisma and anarchic energy. The writer-director uses affective disjunction and constant images of exaggerated Americana not to moralize, but rather to simply represent a hyper-cinematic, genre-codified vision of specific national identities. Spaulding himself acts as an amalgam of cinematic and national reference points, donning a star-spangled top hat in the tradition of Uncle Sam, boasting an arm tattoo of John Wayne and knuckle tattoos reading Love and Hate in a nod to Charles Mitchum’s predatorial character from Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955).

It is important to recognize that House of 1000 Corpses emerges in the wake of Wes Craven’s Scream (1996) and its slew of hip, postmodern teen horror followers (from Urban Legend [1998] to Final Destination [2000] to Valentine [2001]). Much like his musical mentor Alice Cooper, who darkly reinterpreted Beatles and Yardbirds song structures to terrorize a hippy generation gone sour, Zombie invokes postmodern self-awareness while re-orienting the horror genre in its embodied, visceral and sociopolitical roots. Corpses openly accepts its own referentiality and genre-play while also bombarding its viewers with extreme, culturally specific images of debasement and mutilation. This is Americana, screams House of 1000 Corpses, opening space for the more concentrated efforts of its sequel, The Devil’s Rejects.

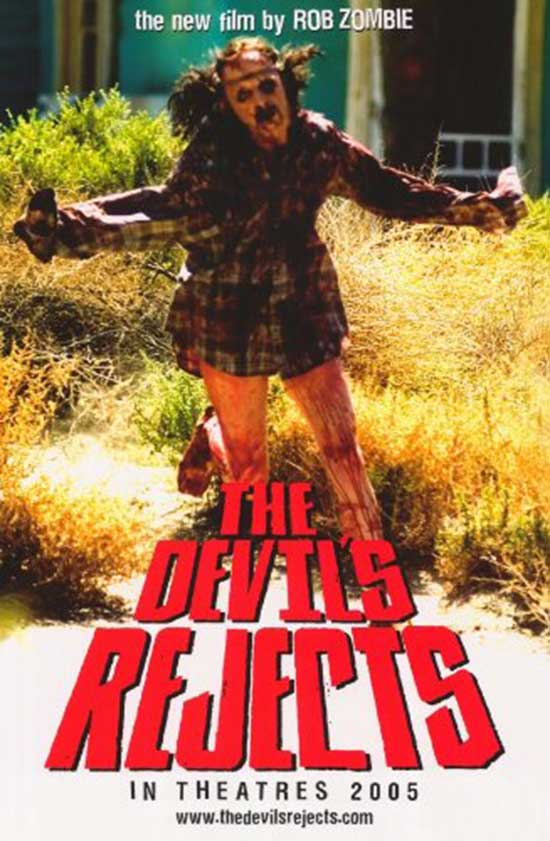

It is worth noting that Rob Zombie’s cinema is not a cinema of finger-wagging miserablism. If anything, Zombie’s work is situated within a space of ambivalence. Nowhere is this made clearer than in his bleak post-Western, The Devil’s Rejects, which offers a sun-baked vision of corrosive colonial America even as it basks in the textures, attitudes and milieus of its genre origins (Westerns, of course, but also exploitation movies, video nasties and rock and roll). If Corpses turns its familiar narrative structure into an exercise in vaudevillian horror deconstruction, then Rejects turns Western conventions against themselves to undo customary ideas surrounding ethical binarity. The film pits ruthless, psychopathic Sherriff Wydell (played with aggressive gusto by William Forsythe) against the Fireflys in a blood-soaked game of cat and bigger cat.

The Devil’s Rejects boasts a radically different aesthetic from its predecessor, with cinematographer Phil Parmet’s 16mm photography explicitly evoking ‘70s grindhouse cinema. Film grain dances over sweaty close-ups and punishingly dry panoramas, incessant sunlight serving as a counterpoint to House’s neon-soaked nightscapes. The plot begins with a police battalion surrounding the Fireflys’ home, a siege planned by Wydell, who invokes the ominous rhetoric of an Old Testament God (“It’s time for us to do what the Good Lord would refer to as a cleansing of the wicked,” he growls before ordering his troops to open fire). A brutal gunfight ensues between the cops and the Fireflys, sending Otis and Baby (Bill Moseley and Sheri Moon Zombie) fleeing while Mama (Leslie Easterbrook) is taken hostage. The plot tracks Wydell’s pursuit of the Fireflys across bleak desert landscapes, punctuated by moments of intense violence perpetrated by both hunter and hunted.

Where House practically scoffs at the notion of morality, Rejects positions itself closer to questions of genre-defined ethics. Wydell views his pursuit of the Fireflys as a mission ordained by God. By contrast, Otis towers over one of his victims and proclaims, “I am the devil, and I’m here to do the devil’s work.”

The film positions its characters as ciphers of good and evil through such explicitly religious invocations, but Zombie is no Manichean thinker. Case in point: Rejects pivots around two central torture sequences, one in which the Fireflys terrorize and sexually humiliate an innocent family inside a motel room, and another near the conclusion in which Wydell plays vigilante and performs pseudo-crucifixions on the serial murderers. Here, Zombie further erodes genre-defined expectations surrounding “self” and “other,” offering instead a vision of the Western as ferocious diagnosis: in Rejects, colonial America is an ambivalent space of relentless, almost unilateral violence and cruelty.

The film climaxes with the Fireflys driving across a deserted U.S. highway toward a police-barricaded border, soundtracked by the majority of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s American rock classic “Free Bird.” The scene culminates with an extended slow-motion shootout between Fireflys and cops, the serial murdering family’s Cadillac surging into a torrent of gore and ammunition. Always conscious of his cinematic lineage, Zombie gestures here to hyper-violent New Hollywood classics Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Wild Bunch (1969).

Calling attention to its own cinematic artifice through ironically nostalgic flashbacks of the Firefly family frolicking outside their home, this climax deconstructs ciphers of American “freedom” (the Fireflys) and “justice” (Wydell and company). Both groups collide in an operatic, almost celebratory display of brutality, one of the most baroque snapshots of Americana in 21st century cinema.

Fourteen years later, the upcoming release of 3 from Hell suggests Rob Zombie has something new to say. Following a trio of empathetic films about trauma and self-loathing (Halloween [2007], Halloween II [2009] and The Lords of Salem [2012]) and 2016’s 31, a contained allegory about contemporary America gone hellbound, the director’s upcoming release raises interesting questions. How will this genre provocateur maintain the bizarre verisimilitude of House and Rejects if 3 from Hell shows the Firefly family somehow surviving the aforementioned highway gunfight? More interestingly, what new genre mode and iconography will Zombie inhabit to continue his career-long study of Americana? If the filmmaker’s existing filmography stands as proof of anything, it is that he has no intention of repeating himself.

By Mike Thorn

Mike Thorn is the author of Darkest Hours, a collection of horror stories. His fiction has appeared in a number of magazines, anthologies and podcasts, including Dark Moon Digest and The NoSleep Podcast. His film criticism has been published in MUBI Notebook, The Film Stage, Vague Visages, The Seventh Row and Bright Lights Film Journal. Visit his website (mikethornwrites.com) or connect with him on Twitter (@MikeThornWrites).

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews