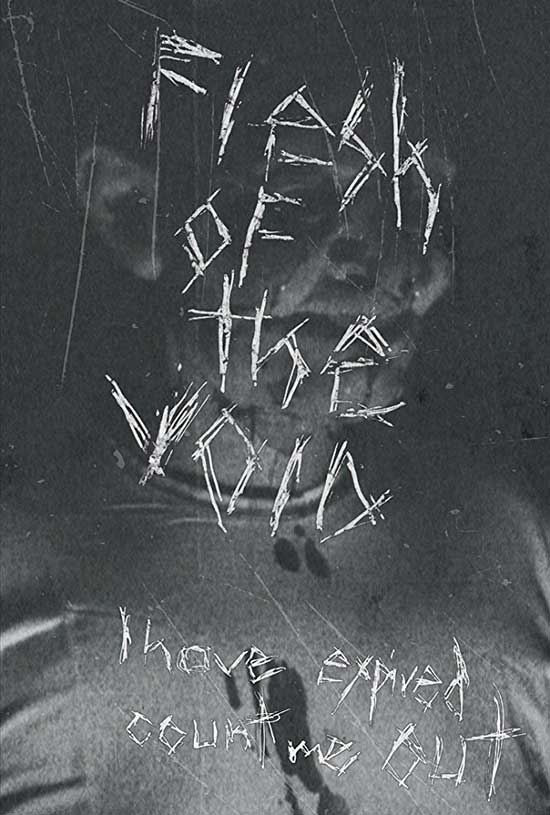

SYNOPSIS:

Flesh of the Void is a terribly disturbing experimental horror film about what it could feel like if death truly were the most horrible thing one could ever experience. It is intended as a trip through the deepest fears of human beings, exploring its subject in a highly grotesque, violent and extreme manner.

REVIEW:

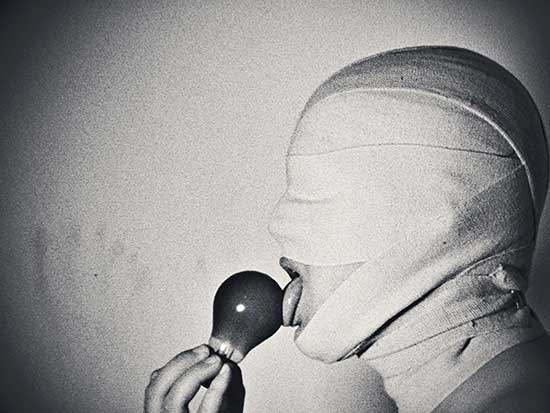

James Quinn’s Flesh of the Void is a demon’s fever dream put to celluloid. The first feature-length release from Sodom & Chimera Productions, home of all of Quinn’s work to date, this film opens with the definition of dying and then delves deeper and deeper into a visual depiction of how the act of dying most likely feels. Shot primarily in black and white on Super 8 and 16mm, Flesh of the Void is an all-out, non-stop assault of nightmarish imagery steeped in blasphemy, nihilism, and controversy.

Written and directed by James Quinn (with a co-writing credit given to someone listed only as “Ju”), there is not a clear, easily decipherable, linear storyline present, nor is there much in the form of dialogue – apart from the occasional unintelligible garbled voice here and there, all we really have are interspersed variations on a cry for help, whether it is a child’s voice begging someone to stop or a man nervously whispering that he can’t move. Instead, we move through each chapter (or act, as they are labelled on screen) with a progression of disturbing characters doing disturbing things to themselves and/or others, the actions fueled by a dark, haunting score that could easily double as the soundtrack played in the creepiest of haunted houses.

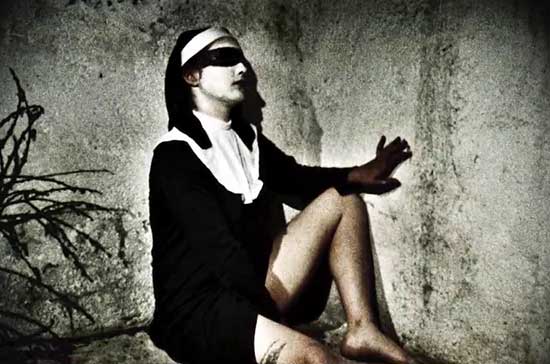

Whereas Quinn’s use of symbolism and metaphor is sometimes more accessible (i.e., in his short film The Temple of Lilith, a character is named “Christianity,” while The Passive Evisceration of the Blackened Soul gives us “Depression,” “Everybody,” and “Minority/The Person”), Flesh of the Void’s characterization, while straightforward – the priest’s character is credited as “Priest” while a man in a gas mask in named “Man in Gas Mask” – tells us less about what they mean than what they are. This can most likely be taken at face value, and instead of trying to read into each character on screen and what they may or may not portray in a deeper sense, we can accept that “Wolfman” is simply a wolfman in this nightmare world, and “Deerman” is just a deerman (side note: most of the characters are credited under assumed aliases; “Priest” is played by Man Without a Face, while Dead Flesh plays “Rapist”). Just because there isn’t a deeper meaning evident on the surface doesn’t mean there isn’t one, and it doesn’t make this portrait of decay any less upsetting.

Flesh of the Void could just as easily be a Norwegian black metal video or the “viral” video recorded straight from the mind of a disturbed little girl in The Ring, one that haunts anyone who watches it for the next seven days before ultimately ending them. There is an authentically gritty, scratched-up look to it, thanks in large part to the format on which it was filmed. It was shot quite masterfully, and edited just as well, a credit to the talents of Quinn as a filmmaker. It has an experimental, artistic feel to it, but it never dips into anything even borderline pretentious. Instead, it ends up displaying the rare quality of being able to disgust and horrify and upset an audience, but still have them raving about how beautiful it all was.

To try and describe too much of what happens on-screen would be a disservice to the film and would inherently fail to get across any of the power and emotion that is on display. Flesh of the Void brings a constant feel of death with it, and establishes this atmosphere from the start with grim, dirty shots of factories and dead trees and pollution and urban decay. The scenes that follow for the next 77 minutes run the gamut from satanic imagery to sexual blasphemy, from brutal violence and genital torture (upsettingly realistic effects work done by James Bell [Dog Dick, Nutsack]) to beautifully disturbed shots reminiscent of the work of Rollin.

Flesh of the Void is not an easily-digested film, nor does it have a familiar plot structure like that of a slasher movie or a possession movie. It is an experimental film that brings its audience to the depths of hell and threatens to leave them there. It is disturbing and upsetting and oftentimes uncomfortable, all of which are no doubt the intention of the director. To compare it to something like Begotten simply because of its gritty, grainy, black and white look is a bit lazy; it is more accurately like if Begotten was directed by Kurt Kren and Otto Muehl with script notes by Marian Dora. Not for the easily offended or faint of heart, Flesh of the Void finds a way to linger in the brain long after viewing, and establishes Quinn as a filmmaker to keep a nervous eye on.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews