SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“In Paris, Doctor Gogol is infatuated with theater actress Yvonne Orlac as he returns to his same box seat for her every performance. Yvonne is married, however, to concert pianist Stephen Orlac. They plan to move to England. When Stephen’s talented hands are crushed in a train wreck, Yvonne asks for Doctor Gogol’s help by operating to save them. Although the doctor can’t save Stephen’s hands, he will do anything to help Yvonne. His solution is to replace the hands with those of an executed knife-throwing murderer. Gogol’s obsession with Yvonne grows while Stephen discovers that his proficiency at the piano has been replaced by an uncanny accuracy with throwing things. The doctor’s next move is to play on Stephen’s mental distress to convince him that he is crazy, and a murderer. It is the only way he can get Yvonne.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Back in 1930, Peter Lorre was a struggling young actor at the Volksbühne (People’s Theatre) in Berlin, usually cast as a troubled person or sexual deviate because of his short physique and round face. Indeed, Lorre tried to exploit his physical limitations (bulging liquid eyes, strangely pitched voice, thickly effeminate lips, small baby face) and best portrayed neurotics and psychopaths. At the People’s Theatre one evening he was noticed by the great German director Fritz Lang, who at that time was toying with the idea of filming a true Düsseldorf police case about a child-murderer whom the underworld aids the authorities in catching. Lang offered Lorre the title role of ‘M’ (1931), standing for ‘Mörder’ or ‘Murderer’. It was an incredible performance. Lorre’s portrayal of the weird whistling child-killer (moon-faced and harmless in appearance, pursuing his quarry down ordinary day-lit paths, tenderly hoarding a cache of children’s shoes in a closet, confessing before a kangaroo court of other criminals) was the acting job of the decade and it catapulted him to instant fame.

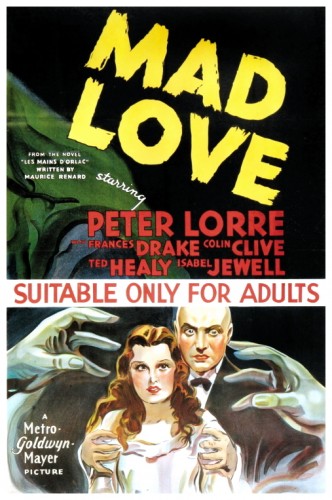

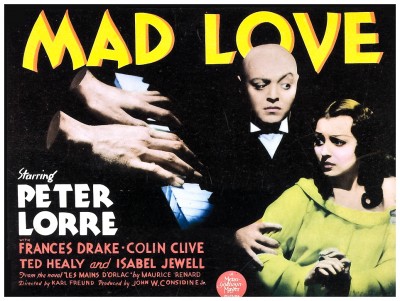

Indeed, one day shortly after the release of ‘M’ an angry mob actually chased and stalked him down a Berlin street. He went on to do other roles in Germany, including the mid-Atlantic villain in the science fiction spectacle Floating Platform One Does Not Answer (1933) and appeared in Alfred Hitchcock‘s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) in England. Then Columbia Pictures offered him the role of Raskolnikov, the student who senselessly kills an old woman, in Josef Von Sternberg‘s Hollywood production of Crime And Punishment (1936). Lorre accepted, but before that picture started shooting, he was offered the role of Doctor Gogol in Mad Love (1935). It was to be his first American role, and he would not get a role as good for many years to come.

Indeed, one day shortly after the release of ‘M’ an angry mob actually chased and stalked him down a Berlin street. He went on to do other roles in Germany, including the mid-Atlantic villain in the science fiction spectacle Floating Platform One Does Not Answer (1933) and appeared in Alfred Hitchcock‘s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) in England. Then Columbia Pictures offered him the role of Raskolnikov, the student who senselessly kills an old woman, in Josef Von Sternberg‘s Hollywood production of Crime And Punishment (1936). Lorre accepted, but before that picture started shooting, he was offered the role of Doctor Gogol in Mad Love (1935). It was to be his first American role, and he would not get a role as good for many years to come.

The Grand Guignol was, for many decades, a real theatre in Paris devoted to short plays of horror and the macabre, performed in ghoulishly realistic detail. The theatre gave its name to such melodrama: Bloodied love trysts, ripper murders, mob vengeance, this was the stuff of the Guignol, all elaborately and shudderingly enacted before the eyes of the audience. In 1935, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios, still trying to jump on the horror film bandwagon initiated by Universal Studios, decided to use the ‘Théâtre des Horreurs’ as a setting in part for a fantastic tale of the medical macabre, a drama of the consequences of a hand graft during a time when the very idea of transplants was shocking and somehow evil, a tampering with the laws of God and nature. The medical transplants of genre cinema were always performed on the gleaming white surgeries of mad scientists, who could be counted on to graft souls as well as flesh. The fantasy film, with its ready stereotype of the alchemist doctor using science as the wand to conjure its enchantments and build his power, explored futurist themes and possibilities in ways that thrilled and frightened its audiences. Certainly hand transplants would be a medical boon of the future, indeed, the hand graftings are performed in Mad Love by a surgeon who has devoted his entire life to acts of good among children, the war-wounded and the poor. But what if the skilled sensitive hands of a pianist were replaced by the hands of a murderer? And what if a residue of soul, a trembling of the killer force, remained in those hands to influence the host body?

The Grand Guignol was, for many decades, a real theatre in Paris devoted to short plays of horror and the macabre, performed in ghoulishly realistic detail. The theatre gave its name to such melodrama: Bloodied love trysts, ripper murders, mob vengeance, this was the stuff of the Guignol, all elaborately and shudderingly enacted before the eyes of the audience. In 1935, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios, still trying to jump on the horror film bandwagon initiated by Universal Studios, decided to use the ‘Théâtre des Horreurs’ as a setting in part for a fantastic tale of the medical macabre, a drama of the consequences of a hand graft during a time when the very idea of transplants was shocking and somehow evil, a tampering with the laws of God and nature. The medical transplants of genre cinema were always performed on the gleaming white surgeries of mad scientists, who could be counted on to graft souls as well as flesh. The fantasy film, with its ready stereotype of the alchemist doctor using science as the wand to conjure its enchantments and build his power, explored futurist themes and possibilities in ways that thrilled and frightened its audiences. Certainly hand transplants would be a medical boon of the future, indeed, the hand graftings are performed in Mad Love by a surgeon who has devoted his entire life to acts of good among children, the war-wounded and the poor. But what if the skilled sensitive hands of a pianist were replaced by the hands of a murderer? And what if a residue of soul, a trembling of the killer force, remained in those hands to influence the host body?

This was the Grand Guignol theme used by MGM for Mad Love (1935) based on the classic French thriller The Hands Of Orlac by Maurice Renard, and previously filmed as a 1925 German silent with Conrad Veidt as Orlac and directed by Robert Wiene, famous for the first version of The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari (1919). For the 1935 version of Mad Love MGM cast Colin Clive as the pianist Orlac. The tall intense Clive, best known for portraying Henry Frankenstein, would this time reverse roles and be the patient rather than surgeon, victim rather than experimenter. He could portray despair and self-torture as well as anyone. For director, the studio hired Karl Freund, the great German cameraman for Metropolis (1927) who had emigrated to the USA to photograph nearly all the great horror films of Universal’s golden age in the thirties, and directed the atmospheric masterpiece The Mummy (1932). With Freund they hoped to capture some of the overwhelming visual weirdness of Wiene’s Germanic original. They hoped to seduce and stun the senses, just as the Grand Guignol did, so they cast in the pivotal role of Doctor Gogol – the surgeon whose ‘mad love’ leads him to perform the transplant and orchestrate its consequences – a young Hungarian actor named Peter Lorre who had made a sensation specialising in the bizarre.

This was the Grand Guignol theme used by MGM for Mad Love (1935) based on the classic French thriller The Hands Of Orlac by Maurice Renard, and previously filmed as a 1925 German silent with Conrad Veidt as Orlac and directed by Robert Wiene, famous for the first version of The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari (1919). For the 1935 version of Mad Love MGM cast Colin Clive as the pianist Orlac. The tall intense Clive, best known for portraying Henry Frankenstein, would this time reverse roles and be the patient rather than surgeon, victim rather than experimenter. He could portray despair and self-torture as well as anyone. For director, the studio hired Karl Freund, the great German cameraman for Metropolis (1927) who had emigrated to the USA to photograph nearly all the great horror films of Universal’s golden age in the thirties, and directed the atmospheric masterpiece The Mummy (1932). With Freund they hoped to capture some of the overwhelming visual weirdness of Wiene’s Germanic original. They hoped to seduce and stun the senses, just as the Grand Guignol did, so they cast in the pivotal role of Doctor Gogol – the surgeon whose ‘mad love’ leads him to perform the transplant and orchestrate its consequences – a young Hungarian actor named Peter Lorre who had made a sensation specialising in the bizarre.

The story starts with actress Yvonne Orlac (Frances Drake) relaxing after her final performance at the Théâtre des Horreurs in Paris. As she listens to her husband Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive) play the piano on the radio, she is greeted by Doctor Gogol (Peter Lorre), who has seen every one of her shows. Unaware of her marriage, Gogol is shocked to learn that Yvonne has decided to move to England with her husband. The doctor leaves the theatre heartbroken, purchases the wax figure of Yvonne’s character and arranges it to be delivered to his home the next day. Later, Stephen Orlac is on his way to Paris from Fontainebleau by train, where he encounters the infamous knife murderer Rollo (Edward Brophy) on the way to his execution by guillotine. Later that night the train crashes, and Yvonne finds her husband with mutilated hands. She takes Stephen to Gogol in an attempt to reconstruct his hands, and Gogol agrees to do so. Gogol uses Rollo’s hands for the transplant, and the operation is a success.

The story starts with actress Yvonne Orlac (Frances Drake) relaxing after her final performance at the Théâtre des Horreurs in Paris. As she listens to her husband Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive) play the piano on the radio, she is greeted by Doctor Gogol (Peter Lorre), who has seen every one of her shows. Unaware of her marriage, Gogol is shocked to learn that Yvonne has decided to move to England with her husband. The doctor leaves the theatre heartbroken, purchases the wax figure of Yvonne’s character and arranges it to be delivered to his home the next day. Later, Stephen Orlac is on his way to Paris from Fontainebleau by train, where he encounters the infamous knife murderer Rollo (Edward Brophy) on the way to his execution by guillotine. Later that night the train crashes, and Yvonne finds her husband with mutilated hands. She takes Stephen to Gogol in an attempt to reconstruct his hands, and Gogol agrees to do so. Gogol uses Rollo’s hands for the transplant, and the operation is a success.

The Orlacs are forced to sell many of their possessions to pay for the surgery, while Stephen finds he is unable to play the piano with his new hands. When a creditor comes to claim their piano, Stephen throws a fountain pen that barely misses his head. Stephen seeks help from his uncaring stepfather Henry Orlac (Ian Wolfe), and angrily throws a knife that just misses Henry and breaks the shop’s window instead. Stephen goes to Gogol to find out why his new hands won’t play the piano yet can throw knives with deadly accuracy. Gogol suggests that Stephen’s problem stems from childhood trauma, but later admits to his assistant Doctor Wong (Keye Luke) that Stephen’s hands had once belonged to Rollo the knife-killer. Gogol begs Yvonne for her love but she refuses, so he suggests that she get away from Stephen, as the shock has affected his mind and she may be in real danger. She angrily rejects Gogol, whose obsession keeps growing.

The Orlacs are forced to sell many of their possessions to pay for the surgery, while Stephen finds he is unable to play the piano with his new hands. When a creditor comes to claim their piano, Stephen throws a fountain pen that barely misses his head. Stephen seeks help from his uncaring stepfather Henry Orlac (Ian Wolfe), and angrily throws a knife that just misses Henry and breaks the shop’s window instead. Stephen goes to Gogol to find out why his new hands won’t play the piano yet can throw knives with deadly accuracy. Gogol suggests that Stephen’s problem stems from childhood trauma, but later admits to his assistant Doctor Wong (Keye Luke) that Stephen’s hands had once belonged to Rollo the knife-killer. Gogol begs Yvonne for her love but she refuses, so he suggests that she get away from Stephen, as the shock has affected his mind and she may be in real danger. She angrily rejects Gogol, whose obsession keeps growing.

Henry Orlac is reported murdered and Stephen receives a note that promises that he will learn the truth about his hands if he goes to a specific address that night. There, a man with metallic hands, neck brace and dark glasses claims to be Rollo, brought back to life by Gogol. Rollo explains that Stephen’s hands were once his, and that Stephen used them to murder Henry. Stephen returns to Yvonne and explains that his hands are those of Rollo, and that he must turn himself in to the police. A panic-stricken Yvonne goes to Gogol’s home to find him driven completely mad. Gogol thinks that his wax replica of Yvonne has come to life, embraces her and begins to strangle her. Happily, however, Stephen has managed to convince the police that Gogol is somehow involved in the murder. They arrive at the doctor’s house just in tome to rescue Yvonne, as Stephen with his scarred right hand tosses a knife square into Gogol’s back. The film’s final shot is of Gogol sinking to the floor, a victim of the deadly aim he himself had grafted upon the pianist Orlac.

Henry Orlac is reported murdered and Stephen receives a note that promises that he will learn the truth about his hands if he goes to a specific address that night. There, a man with metallic hands, neck brace and dark glasses claims to be Rollo, brought back to life by Gogol. Rollo explains that Stephen’s hands were once his, and that Stephen used them to murder Henry. Stephen returns to Yvonne and explains that his hands are those of Rollo, and that he must turn himself in to the police. A panic-stricken Yvonne goes to Gogol’s home to find him driven completely mad. Gogol thinks that his wax replica of Yvonne has come to life, embraces her and begins to strangle her. Happily, however, Stephen has managed to convince the police that Gogol is somehow involved in the murder. They arrive at the doctor’s house just in tome to rescue Yvonne, as Stephen with his scarred right hand tosses a knife square into Gogol’s back. The film’s final shot is of Gogol sinking to the floor, a victim of the deadly aim he himself had grafted upon the pianist Orlac.

Karl Freund was never to direct another film but, as one of the world’s greatest cinematographers, he remained extremely active especially in television until his death in 1969. Since Freund was busy directing, he wisely hired one of Hollywood’s best photographers to shoot Mad Love. Gregg Toland was famous for his innovative use of lighting and other techniques such as deep focus, examples of which can be found in his work for top-shelf directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Erich Von Stroheim, King Vidor, Orson Welles and William Wyler. Also worthy of note is composer Dimitri Tiomkin, who was to become best-known for his western soundtracks, including Duel In The Sun (1946), High Noon (1952), Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (1957) and The Alamo (1961). Tiomkin received an amazing twenty-two Oscar nominations and won four of them, three for Best Original Score – High Noon, The High And The Mighty (1954) and The Old Man And The Sea (1958) – and one for Best Song for The Ballad Of High Noon better known as Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling, in fact he was the first composer to win in both categories for the same film.

Karl Freund was never to direct another film but, as one of the world’s greatest cinematographers, he remained extremely active especially in television until his death in 1969. Since Freund was busy directing, he wisely hired one of Hollywood’s best photographers to shoot Mad Love. Gregg Toland was famous for his innovative use of lighting and other techniques such as deep focus, examples of which can be found in his work for top-shelf directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Erich Von Stroheim, King Vidor, Orson Welles and William Wyler. Also worthy of note is composer Dimitri Tiomkin, who was to become best-known for his western soundtracks, including Duel In The Sun (1946), High Noon (1952), Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (1957) and The Alamo (1961). Tiomkin received an amazing twenty-two Oscar nominations and won four of them, three for Best Original Score – High Noon, The High And The Mighty (1954) and The Old Man And The Sea (1958) – and one for Best Song for The Ballad Of High Noon better known as Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling, in fact he was the first composer to win in both categories for the same film.

For Lorre, very few roles thereafter were to bring him so close to centre stage. His specially shaven head accentuating his bulging eyes, his soul-piercing anguish throbbing through such lines as, “I, a poor peasant, have conquered science! Why cannot I conquer love?” made his portrayal of the iconoclastic scientist suddenly exposed to and destroyed by human emotion a classic of its kind. Most of his roles in the years immediately following were confined to B-grade quickies although, as in the Mister Moto series of mysteries, he tried to make the most of them. The next decade he was paired with Sydney Greenstreet in The Maltese Falcon (1941), and the success of the combination led (for Lorre) to a contract with Warner Brothers studios and roles of stature once more. Oddly enough, he was rarely to play a scientist again.

For Lorre, very few roles thereafter were to bring him so close to centre stage. His specially shaven head accentuating his bulging eyes, his soul-piercing anguish throbbing through such lines as, “I, a poor peasant, have conquered science! Why cannot I conquer love?” made his portrayal of the iconoclastic scientist suddenly exposed to and destroyed by human emotion a classic of its kind. Most of his roles in the years immediately following were confined to B-grade quickies although, as in the Mister Moto series of mysteries, he tried to make the most of them. The next decade he was paired with Sydney Greenstreet in The Maltese Falcon (1941), and the success of the combination led (for Lorre) to a contract with Warner Brothers studios and roles of stature once more. Oddly enough, he was rarely to play a scientist again.

Mad Love has inspired many films since and has been remade at least twice. The Beast With Five Fingers (1946) was a variant on the theme again starring Lorre and, in the 1960 version, the character of Gogol is done away with altogether and Christopher Lee, as a sort of paranoid stage magician named Nero, takes on the role of villain. The cinematic image of the surgeon daring and sinister enough to experiment with transplants is fading. Today severed hands and limbs are sewn back on without a second’s thought. Of course, Mad Love is concerned not with hands but with souls, and whether some of a murderer’s strength and character and evil can be grafted onto another. It also explores an even more traditional theme, one that is curiously satisfying: Even the wisest of men can be driven insane by love. With that deep thought in mind I’ll thank you for reading, and look forward to your company next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Mad Love has inspired many films since and has been remade at least twice. The Beast With Five Fingers (1946) was a variant on the theme again starring Lorre and, in the 1960 version, the character of Gogol is done away with altogether and Christopher Lee, as a sort of paranoid stage magician named Nero, takes on the role of villain. The cinematic image of the surgeon daring and sinister enough to experiment with transplants is fading. Today severed hands and limbs are sewn back on without a second’s thought. Of course, Mad Love is concerned not with hands but with souls, and whether some of a murderer’s strength and character and evil can be grafted onto another. It also explores an even more traditional theme, one that is curiously satisfying: Even the wisest of men can be driven insane by love. With that deep thought in mind I’ll thank you for reading, and look forward to your company next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

You are a very eloquent tall, posh skeleton! Thank you for a review of one of my favorite movies!

“a residue of soul, a trembling of the killer force”

great description!