SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“In 1880 Sir Oliver Lindenbrook, just knighted, is a renowned scientist teaching at the University of Edinburgh. He inadvertently discovers evidence pointing to Arne Saknussem, an Icelandic scientist from a few centuries earlier, having found a pathway from the volcanoes in Iceland to the center of the earth. He writes to Swedish Professor Peter Göteborg, an expert in world volcanoes, with his findings before proceeding with an expedition to the center of the earth. Instead of hearing back from Göteborg, Lindenbrook learns that Göteborg has taken the information to make it to the center before him. Lindenbrook and one of his students, Alec McKuen who is engaged to Lindenbrook’s niece, quickly embark for Iceland for their own journey to the center to beat Göteborg. In Iceland, they however find Göteborg murdered, seemingly by Count Saknussem, a descendant of Arne’s and a scientist in his own right. By now, they have recruited Hans Belker, a brawny Icelandic farmer with his beloved pet duck Gertrude, to come along to do much of the manual work. But they must also reluctantly include onto the team Carla Göteborg, Professor Göteborg’s wife, who will not provide them with her husband’s prized equipment otherwise. As the four with Gertrude proceed on their precarious journey with Carla and Lindenbrook often at odds with each other and aware of the possible dangers before them, they are initially unaware of the danger behind them, namely Count Saknussem, who needs to rely somewhat on Lindenbrook’s expertise but who will stop at nothing to beat Lindenbrook to the center as he believes this project and its associated glory rightfully belongs to him as a Saknussem. The question ultimately becomes what to do if they make it to the center.”

REVIEW:

Thematically, science fiction films in the sixties at last began to diversify and to get away from the bug-eyed monsters that typified the genre during the fifties. There is not one movie made between 1960 and 1970 can be said to be a typical sixties science fiction film, though the decade did see a small trend in satirical science fiction films such as Doctor Strangelove (1964), The President’s Analyst (1967), The Day The Fish Came Out (1967), Barbarella (1968) and The Bed Sitting Room (1969). The sixties also blurred the edges between science fiction films and other cinema genres, a trend that began with the James Bond film Doctor No (1962), which assimilated traditional science fiction elements (mad scientists, futuristic laboratories, mysterious rays, spaceships, etc.) into the framework of an ultra-slick contemporary action-thriller.

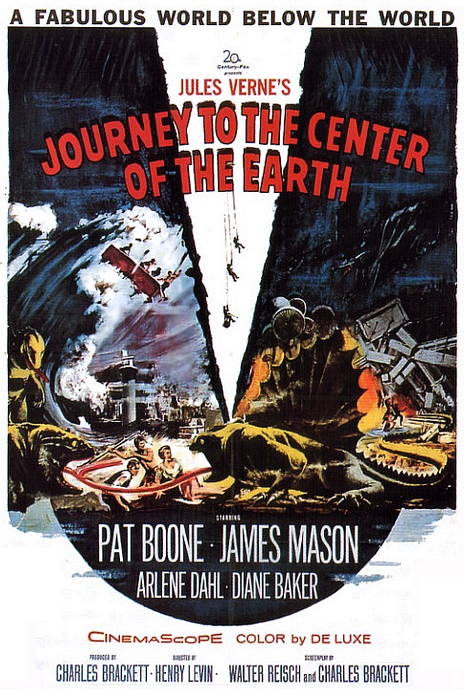

The sixties also saw many filmmakers return to written science fiction as a source of original material, though Hollywood scriptwriters continued to ‘adapt’ and ‘re-imagine’ the material into a state suitable for the big screen, with the usual dire results. Once again the work of my old drinking buddies Jules Verne and H.G. Wells was mined for filmable stories, along with the work of other authors like Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs, John Wyndham, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Sheckley. Based on the success of Walt Disney‘s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954) and Michael Todd‘s Around The World In Eighty Days (1956), 20th Century Fox gave the go-ahead for a big-budget CinemaScope production of Journey To The Center Of The Earth (1959) and, like those earlier films, the bigger budget proved to be a good investment, resulting in a huge box-office hit.

The sixties also saw many filmmakers return to written science fiction as a source of original material, though Hollywood scriptwriters continued to ‘adapt’ and ‘re-imagine’ the material into a state suitable for the big screen, with the usual dire results. Once again the work of my old drinking buddies Jules Verne and H.G. Wells was mined for filmable stories, along with the work of other authors like Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs, John Wyndham, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Sheckley. Based on the success of Walt Disney‘s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954) and Michael Todd‘s Around The World In Eighty Days (1956), 20th Century Fox gave the go-ahead for a big-budget CinemaScope production of Journey To The Center Of The Earth (1959) and, like those earlier films, the bigger budget proved to be a good investment, resulting in a huge box-office hit.

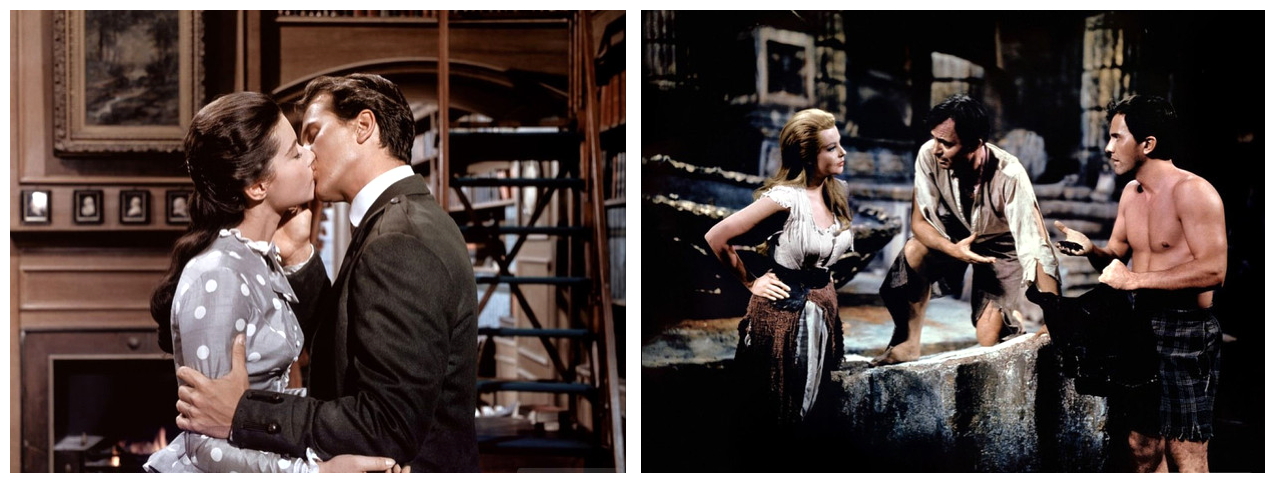

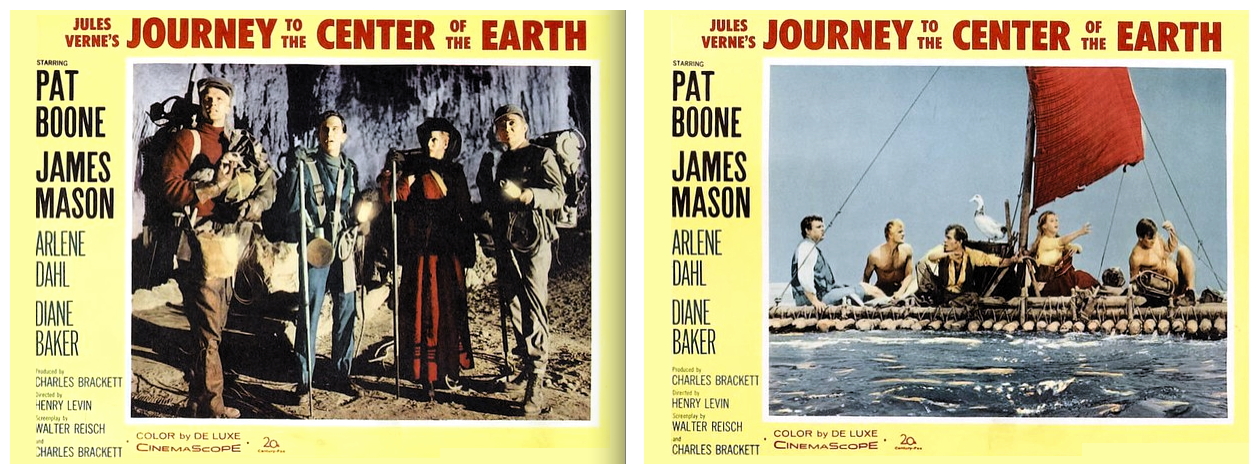

Although made in 1959, Journey To The Center Of The Earth wasn’t officially released until January 1960, beginning this new cycle of films adapted from science fiction classics, and is a moderately entertaining production, despite the presence of Pat Boone in the lead role. Fortunately, James Mason is also present and contributes his usual quota of style and charm. He plays Scottish Professor Lindenbrook who is given a paperweight and discovers that it contains a message from a man who claims to have been to the centre of the Earth. He immediately decides to launch a similar expedition, taking with him his daughter Jenny (Diane Baker), student Alec McKuen (Pat Boone), recently widowed Carla Göteborg (Arlene Dahl), Icelandic guide Hans (Peter Ronson) and Gertrude the duck.

Although made in 1959, Journey To The Center Of The Earth wasn’t officially released until January 1960, beginning this new cycle of films adapted from science fiction classics, and is a moderately entertaining production, despite the presence of Pat Boone in the lead role. Fortunately, James Mason is also present and contributes his usual quota of style and charm. He plays Scottish Professor Lindenbrook who is given a paperweight and discovers that it contains a message from a man who claims to have been to the centre of the Earth. He immediately decides to launch a similar expedition, taking with him his daughter Jenny (Diane Baker), student Alec McKuen (Pat Boone), recently widowed Carla Göteborg (Arlene Dahl), Icelandic guide Hans (Peter Ronson) and Gertrude the duck.

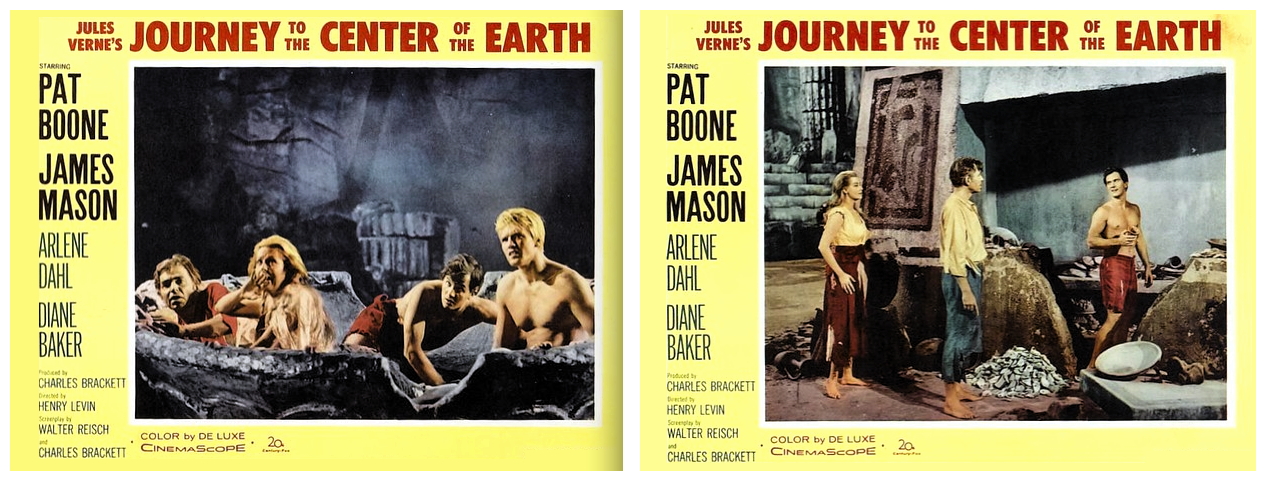

The film is steadily paced (which is a nice way to say it’s far too long at two hours twelve minutes) with much scene-setting and intrigue before the expedition begins, and frequent digressions thereafter. We pause for love interest, battle-of-the-sexes comedy relief, a couple of forgettable songs and some cute business with Gertrude the duck that, surprisingly, ends up being eaten by the film’s chief villain, Count Saknussem (Thayer David). Once underground, the ‘Boy’s Own Adventures’ move up a gear, as the expedition is beset by falls, floods and sabotage before a rip-roaring last act in which our heroes fight off the carnivorous attentions of amusingly magnified lizards. Then in the gleefully absurd finale, the voyagers burst back up through the earth’s crust on a geyser of molten lava.

The film is steadily paced (which is a nice way to say it’s far too long at two hours twelve minutes) with much scene-setting and intrigue before the expedition begins, and frequent digressions thereafter. We pause for love interest, battle-of-the-sexes comedy relief, a couple of forgettable songs and some cute business with Gertrude the duck that, surprisingly, ends up being eaten by the film’s chief villain, Count Saknussem (Thayer David). Once underground, the ‘Boy’s Own Adventures’ move up a gear, as the expedition is beset by falls, floods and sabotage before a rip-roaring last act in which our heroes fight off the carnivorous attentions of amusingly magnified lizards. Then in the gleefully absurd finale, the voyagers burst back up through the earth’s crust on a geyser of molten lava.

Scriptwriters Walter Reisch and Charles Brackett (who also produced the movie) turned Verne’s somewhat gloomy and claustrophobic novel into a tongue-in-cheek romp with plenty of colourful sets, state-of-the-art special effects and moody Bernard Herrmann score, but the overall tone of the film can be best demonstrated by the ending, which has Pat Boone blown out of a volcano, losing all his clothes in the process, lands in a tree where he is discovered by a couple of passing nuns, and makes his escape while holding a live sheep to his naked groin. Boone didn’t even want to appear in the movie but was talked into it by his agent, and received top-billing despite his wavering accent. Years later he told me he was glad he did do it because of the regular residual cheques it brings in and it’s the movie he’s best remembered for.

Scriptwriters Walter Reisch and Charles Brackett (who also produced the movie) turned Verne’s somewhat gloomy and claustrophobic novel into a tongue-in-cheek romp with plenty of colourful sets, state-of-the-art special effects and moody Bernard Herrmann score, but the overall tone of the film can be best demonstrated by the ending, which has Pat Boone blown out of a volcano, losing all his clothes in the process, lands in a tree where he is discovered by a couple of passing nuns, and makes his escape while holding a live sheep to his naked groin. Boone didn’t even want to appear in the movie but was talked into it by his agent, and received top-billing despite his wavering accent. Years later he told me he was glad he did do it because of the regular residual cheques it brings in and it’s the movie he’s best remembered for.

Amongst an uninspiring cast, Mason emerges clearly as the film’s strongest performance. As a matter of fact, he had very little patience for Arlene Dahl’s preening and their relationship off-screen was very much like what we see on-screen. Nevertheless, Mason is wonderful as Professor Lindenbrook, the crotchety Edinburgh scientist whose devotion to his quest never overshadows his commitment to social proprieties: “Let us have tea with a double ration of raisins. Ladies on the left, gentleman on the right,” he announces almost half-way to the centre of the earth. The director was Henry Levin, who made more than fifty mediocre movies, the most interesting being Cry Of The Werewolf (1944), Where The Boys Are (1960), The Wonderful World Of The Brothers Grimm (1962) and two of the Matt Helm adventures, Murderer’s Row (1966) and The Ambushers (1967) starring another old drinking buddy of mine, Dean Martin.

Amongst an uninspiring cast, Mason emerges clearly as the film’s strongest performance. As a matter of fact, he had very little patience for Arlene Dahl’s preening and their relationship off-screen was very much like what we see on-screen. Nevertheless, Mason is wonderful as Professor Lindenbrook, the crotchety Edinburgh scientist whose devotion to his quest never overshadows his commitment to social proprieties: “Let us have tea with a double ration of raisins. Ladies on the left, gentleman on the right,” he announces almost half-way to the centre of the earth. The director was Henry Levin, who made more than fifty mediocre movies, the most interesting being Cry Of The Werewolf (1944), Where The Boys Are (1960), The Wonderful World Of The Brothers Grimm (1962) and two of the Matt Helm adventures, Murderer’s Row (1966) and The Ambushers (1967) starring another old drinking buddy of mine, Dean Martin.

It feels a little like a Disney live-action feature of the era, not least 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, an earlier Verne adaptation in which James Mason also starred. Less inhibited by scientific rigor than the fantasies of Wells, Verne’s adventures make a virtue of their almost childlike sense of wonder and enchantment, and this beguiling good-natured story remains one of the most successful translations of that spirit to the medium of cinema. Admittedly, a lot of suspension of disbelief is required, but there is also something delightful about the sheer madness of it all. Though the effects now seem charmingly dated and many of the cavernous sets are obviously studio-bound, the artificiality of the production seems somehow very in keeping with the Victorian imagination animating it. At no point does it try to convince us (as Wells’ tries to do) through realistic detail and techno-babble – it’s more like a grand eruption of 19th century imagination, painted in the broadest strokes.

Lyle Wheeler, Franz Bachelin, Herman Blumenthal, Walter Scott and Joseph Kish were all nominated for Oscars for their set design and special effects, and Carlton Faulkner was nominated for best sound. With a budget of around US$3.5 million, Journey To The Center Of The Earth grossed well over US$5 million at the box-office but, despite its popularity with the film-going public, it was hardly a critical hit. In his 1960 New York Times review, Bosley Crowther wrote: “The film is really not very striking make-believe, when all is said and done. The earth’s interior is somewhat on the order of an elaborate amusement-park tunnel of love. And the attitudes of the people – toward each other and toward another curious man who happens to be exploring down there at the same time – are conventional and just a bit dull.”

Compare that opinion with a more recent retrospect from Ian Nathan of Empire magazine: “It has dated a fair bit, but it’s a film that takes its far-fetchedness seriously, and delivers a thrilling adventure untrammelled by cheese, melodrama or ludicrous tribes of extras, shabbily dressed bird-beings or lizard men. The film is still captivating despite the obviously dated effects.” Bottom line? “A silly but fun movie with everything you’d ever want from a science fiction blockbuster: Heroic characters, menacing villains, monsters, big sets and special effects.” It’s with this thought in mind I’ll now bid you a good night and farewell until we meet again to grope blindly around the bear-trap known as Hollywood for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News! Toodles!

Compare that opinion with a more recent retrospect from Ian Nathan of Empire magazine: “It has dated a fair bit, but it’s a film that takes its far-fetchedness seriously, and delivers a thrilling adventure untrammelled by cheese, melodrama or ludicrous tribes of extras, shabbily dressed bird-beings or lizard men. The film is still captivating despite the obviously dated effects.” Bottom line? “A silly but fun movie with everything you’d ever want from a science fiction blockbuster: Heroic characters, menacing villains, monsters, big sets and special effects.” It’s with this thought in mind I’ll now bid you a good night and farewell until we meet again to grope blindly around the bear-trap known as Hollywood for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews