SYNOPSIS:

A mother and her 6 year old daughter move into a creepy apartment whose every surface is permeated by water.

REVIEW:

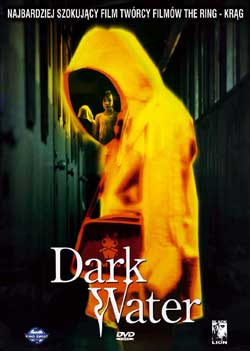

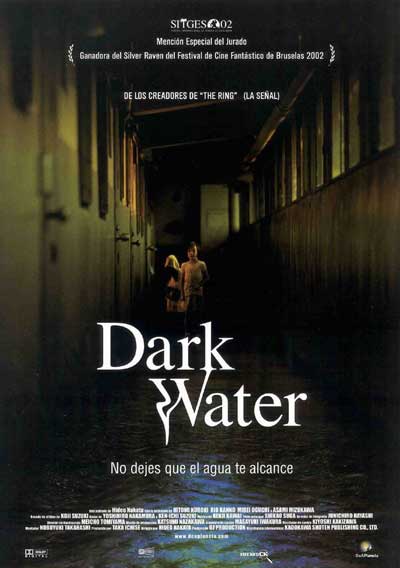

Following hot on the heels of the execrable Sadako 3D, here we have the perfect antidote. Dark Water is Hideo Nakata’s second adaptation of a Kôji Suzuki story, and it is also one of several Japanese horror flicks to have been given the dubious honour of a Hollywood remake in the wake of Gore Verbinski’s success with The Ring.

What’s immediately apparent is that Dark Water contains many of the familiar touchstones from the Nakata’s first Suzuki adaptation, Ring. There’s the beautiful, newly-divorced mother (Yoshimi) and her precocious child (Ikuko), the ghostly little girl who kills from beyond the grave (Mitsuko), and even the use of photographs with the faces eerily blurred out. It would be easy to accuse Nakata of rehashing his masterpiece for a fast buck, but in spite of the wealth of familiar elements, Dark Water is different enough from its famous predecessor to be judged on its own merits.

This is a much more claustrophobic movie than Ring, and much less grand and sweeping in its scope. While the antagonist is still a creepy little dead girl in desperate need of closure, this film is really about the hostility of an environment, a classic haunted house story. The new spin on the old idea is that the haunted house is now an apartment block, an unprepossessing and rundown bit of brutalist architecture, run by slumlords who are apparently unaware of the curse attached to their building. There is no creepy butler, no homicidal maidservant, no grouchy groundskeeper—just the feckless buck-passers all too familiar to Generation Rent.

This is the great strength of Dark Water: Nakata’s wonderful knack for finding horror on the prosaic. A child’s plastic handbag becomes a talisman of evil every bit as potent as Lovecraft’s Necronomicon. An ugly, mid-20th century apartment building becomes as forbidding as Poe’s House of Usher or Shirley Jackson’s Hill House. Everyday scenes in offices and classrooms take on an ominous aspect thanks to the carefully constructed mise on scène, with a decidedly Kubrickian use of framing, composition and camera movement. The debt is acknowledged late on in the film, when lift doors open to release thousands of gallons of water, echoing a much bloodier shot in The Shining.

Dark Water also differs from Ring in that it is a horror of paranoia and self-doubt, after the manner of Rosemary’s Baby or Don’t Look Now. Yoshimi is an unwilling Cassandra, a determined rationalist foundering in the face of supernatural forces, and in the shadow of her own former mental illness. Her plight is only worsened by the inconvenient fact that most of the creepy phenomena plaguing her and Ikuko are easily explained away by the poor maintenance of the building and her own reactions to the pressures in her life—not least the custody battle she appears to be losing. There is also the uncomfortable knowledge that Ikuko would probably be safe from the malevolent forces in the building if she went to live with her uncaring bastard of a father.

To be brutally honest, there are points in this film where it does feel like a rehash of ideas already explored in Ring, but this is more down to the common origin of the source material than anything else. Thankfully it is never enough to really hamper the enjoyability of the film. The tension is deftly built up minute by minute, even when nothing very much is happening. The final half hour is very gripping, packed full of thrills (and indeed spills), and the payoff in the climax is a satisfying one. On the downside, this is then followed by a clumsily handled denouement which feels a little tacked-on, and the excellent sound design is let down by some jarringly cheesy music towards the end. But by that time the viewer has had their money’s worth of entertainment, so there’s little harm done. Dark Water is not the equal of Ring by any stretch of the imagination, but it is still a first class horror film.

Dark Water (2002)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews