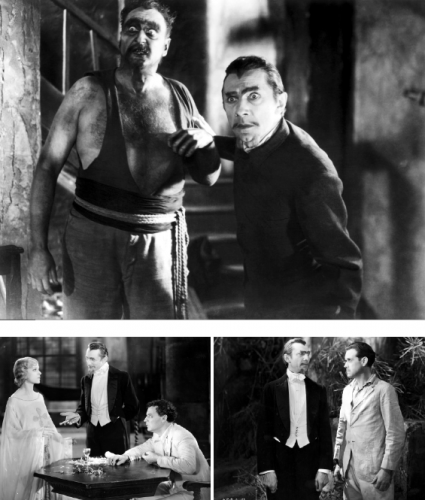

In 1924 the first major theatrical production of Bram Stoker’s Dracula opened on stage in England. Starring writer-actor Hamilton Deane, the play was such a success that it was transferred to London’s West End. In 1927 the production opened on Broadway starring a young Hungarian actor named Bela Lugosi. Universal pictures purchased the screen rights that same year for US$40,000, intending to make the first ‘talkie’ version of the film with their resident horror kings, Lon Chaney Senior and director Tod Browning. The combination should have been a natural – after all, the two had just completed the silent pseudo-vampire thriller London After Midnight (1927).

In 1924 the first major theatrical production of Bram Stoker’s Dracula opened on stage in England. Starring writer-actor Hamilton Deane, the play was such a success that it was transferred to London’s West End. In 1927 the production opened on Broadway starring a young Hungarian actor named Bela Lugosi. Universal pictures purchased the screen rights that same year for US$40,000, intending to make the first ‘talkie’ version of the film with their resident horror kings, Lon Chaney Senior and director Tod Browning. The combination should have been a natural – after all, the two had just completed the silent pseudo-vampire thriller London After Midnight (1927).

But Chaney was unhappy with the new medium of sound, and told me that he thought it brought a crassness to the art of silent film-making. For two years Browning and Universal tried to convince him otherwise. In 1930 Chaney capitulated and agreed to remake one of his earlier screen successes, The Unholy Three (1924). Discussions between Chaney, Browning and Universal continued concerning a screen version of the popular vampire play, but tragedy intervened when Chaney passed away due to bronchial cancer just one month after completing his only sound film.

With Chaney dead, Universal started casting around for an actor to play the Count of the Carpathians, with Ian Keith, Victor Jory and William Courtney all being considered. In early September 1930, Lugosi was screen-tested and production started within a few weeks. Oddly enough, Dracula (1930) doesn’t stand up very well today – where Browning’s silent films had a visual fluidity, Dracula remained stage-bound and overly ‘talky’, but the film proved to be a smash hit with audiences and so began the first Golden Age of screen horror, with Universal Pictures leading the way. Before we get stuck-in, I must profusely thank Wikipedia for assisting me with my research.

THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935): James Whale initially rejected the thought of a sequel to Frankenstein (1931), but with the vast investment in place from Universal there was very little choice – thankfully. More than just a sequel, The Bride Of Frankenstein is a reflection of James Whale, as his own personality is injected into the film producing a wonderful blend of humour and terror.

THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935): James Whale initially rejected the thought of a sequel to Frankenstein (1931), but with the vast investment in place from Universal there was very little choice – thankfully. More than just a sequel, The Bride Of Frankenstein is a reflection of James Whale, as his own personality is injected into the film producing a wonderful blend of humour and terror.

By far the more superior offering than the earlier Frankenstein, the sequel really brings the monster to life. It is Boris Karloff the actor that stands tall as he allows us to warm to the monster, feeling compassion and sadness for a creature that just wants to love and to be loved. The real villain emerges in the form of the horrendous Doctor Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). There are strokes of genius from both Whale and Karloff, especially as we see the all-drinking, all-smoking, all-dancing monster find solace with a blind hermit. It’s even more apparent in The Bride Of Frankenstein how misunderstood our monster really is, and how he has become a nightmare in broad daylight. A film that gave us the first and perhaps only iconic female monster, provided a joyous musical score, injected the genre with camp black comedy and, above all, gave us one of the greatest horror films of all-time.

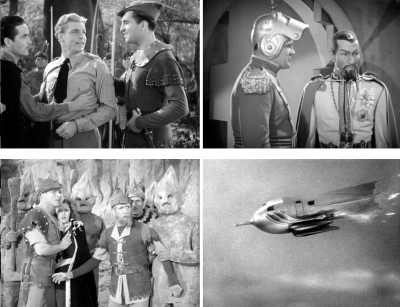

BUCK ROGERS (1939): Director Ford Beebe, who also worked on Flash Gordon (1938), came straight from The Phantom Creeps (1939) and then went back to finish Flash Gordon Conquers The Universe (1940). Buck Rogers stars Buster Crabbe or, as his family knew him, Lawrence. Now, Lawrence ‘Larry’ ‘Buster’ Crabbe had previously starred in two Flash Gordon serials, a couple of Tarzan movies and a long string of westerns, so it was only natural for Universal to decide he was perfect as the heroic Buck Rogers, aka that blonde guy who saves the universe but isn’t Flash Gordon. Actually, Buster Crabbe wasn’t the first actor to play Buck Rogers in-the-flesh, so to speak.

That honour goes to an unknown man who played Buck in a Virginia department store, instead of their regular Santa Claus. Santa was off conquering Martians at the time, I think it was an exchange program of sorts. It strikes me that Buck Rogers is not unlike a male fantasy come to life. Just think of it – Buck gets to take a nice five-hundred-year-long sleep-in. With my busy schedule, I’m ecstatic if I can get twenty minutes nap on the weekend. Then, when he wakes up, Buck is the smartest, most dynamic guy around. In reality he’d be treated like something that’s escaped from the zoo. And finally, everyone needs Buck to go on exciting missions, fight the bad guys, test exotic equipment and crash rocket ships – out of the half-dozen flights Buck makes, he only lands successfully once. It’s easy to see the bullet cars used in the movie are the same ones from Flash Gordon’s Trip To Mars (1938), and even the script is rather suspect.

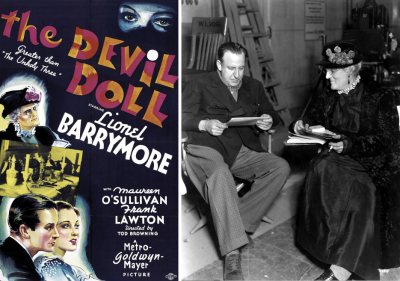

THE DEVIL-DOLL (1936): Directed by Tod Browning and starring Lionel Barrymore in drag, The Devil-Doll was adapted from the novel Burn Witch Burn! by Abraham Merritt. Paul Lavond, who was wrongly convicted of robbing his own Paris bank and killing a security guard seventeen years before, escapes Devil’s Island with a scientist who is trying to create a formula to reduce people to one-sixth of their original size. The intended purpose of the formula is to make the Earth’s limited resources (water, food, energy, etc.) last longer for an ever-growing population. The scientist dies after their escape.

THE DEVIL-DOLL (1936): Directed by Tod Browning and starring Lionel Barrymore in drag, The Devil-Doll was adapted from the novel Burn Witch Burn! by Abraham Merritt. Paul Lavond, who was wrongly convicted of robbing his own Paris bank and killing a security guard seventeen years before, escapes Devil’s Island with a scientist who is trying to create a formula to reduce people to one-sixth of their original size. The intended purpose of the formula is to make the Earth’s limited resources (water, food, energy, etc.) last longer for an ever-growing population. The scientist dies after their escape.

Lavond joins the scientist’s widow Malita and uses the shrinking technique to obtain revenge on the three former business associates who had framed him and to vindicate himself. Lavond clears his name and secures the future happiness of his estranged daughter Lorraine in the process. Malita isn’t satisfied, and wants to continue to use the formula for personal gain. She tries to kill Paul when he announces that he is finished with their partnership, having accomplished all he intended, but she ends up blowing up their lab and killing herself. To save his daughter from scandal, Paul tells Lorraine’s fiancee about what happened. He meets his daughter, pretending to be the deceased Marcel. He tells Lorraine that Lavond died during their escape from prison, but that he loved her very much. Lavond then departs, planning to leave France forever.

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1931): Directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Fredric March, this is yet another adaptation of The Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde, the Robert Louis Stevenson tale of a man who takes a potion which turns him from a mild-mannered man of science into a crude homicidal maniac. The secret of the astonishing transformation scenes was not revealed for decades, but apparently a series of coloured filters matching the makeup was used, enabling the makeup applied in contrasting colours, to be gradually exposed or made invisible. The change in colour was not visible on black-and-white film, a process that was duplicated in the Mel Brooks film Young Frankenstein (1974). Perc Westmore‘s makeup for Hyde, simian and hairy with large canine teeth influenced greatly the image of Hyde in popular culture. This reflected the implication of Hyde as embodying repressed evil and hence being semi-evolved or simian in appearance. The characters of Muriel Carew and Ivy Pearson do not appear in Stevenson’s original story but do appear in the 1887 stage version by playwright Thomas Russell Sullivan. My old friend John Barrymore was originally asked to play the lead role but he demanded such a large salary that they gave the part to another man, namely Fredric March, who won the Best Actor Oscar for his dual role.

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1931): Directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Fredric March, this is yet another adaptation of The Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde, the Robert Louis Stevenson tale of a man who takes a potion which turns him from a mild-mannered man of science into a crude homicidal maniac. The secret of the astonishing transformation scenes was not revealed for decades, but apparently a series of coloured filters matching the makeup was used, enabling the makeup applied in contrasting colours, to be gradually exposed or made invisible. The change in colour was not visible on black-and-white film, a process that was duplicated in the Mel Brooks film Young Frankenstein (1974). Perc Westmore‘s makeup for Hyde, simian and hairy with large canine teeth influenced greatly the image of Hyde in popular culture. This reflected the implication of Hyde as embodying repressed evil and hence being semi-evolved or simian in appearance. The characters of Muriel Carew and Ivy Pearson do not appear in Stevenson’s original story but do appear in the 1887 stage version by playwright Thomas Russell Sullivan. My old friend John Barrymore was originally asked to play the lead role but he demanded such a large salary that they gave the part to another man, namely Fredric March, who won the Best Actor Oscar for his dual role.

DRACULA (1930): Dracula was originally intended as a vehicle for Lon Chaney Senior, who sadly passed away, so Universal turned to the relatively unknown Bela Lugosi, who was very familiar with the role following a two-year stint in the stage production. This opportunity for the Hungarian actor would not only change his life, but would forever associate Lugosi with Dracula (and later Ed Wood). Although no-where near as chilling as the silent Nosferatu (1922) which remains an unparalleled masterpiece, the 1931 version introduced the accent and the look that has become common practice. A frenzied Renfield (Dwight Frye) and some wonderful camera work from Carl Freund also deserve kudos. Fangs for the memories.

FLASH GORDON (1936): Told in thirteen weekly installments, it was the first screen adventure for the comic-strip character Flash Gordon, and tells the story of his first visit to the planet Mongo and his encounter with the evil Emperor Ming The Merciless. Lawrence ‘Larry’ ‘Buster’ Crabbe played the central role in Flash Gordon which supposedly had a budget of over a million dollars, but was later revealed to be only around US$350,000. A lot of props and other elements were recycled from earlier Universal productions: The watchtower from Frankenstein (1931) appeared as Zarkov’s base; The Egyptian idol from The Mummy (1932) became the idol of the Great God Tao; Shots of Earth from space came from The Invisible Ray (1936); The rocket ships were reused from Just Imagine (1930); An entire dance sequence from The Midnight Sun (1927) was used; A laboratory set from The Bride Of Frankenstein (1935); Ming’s attack on Earth used newsreel footage; And the music was recycled from several other films.

FLASH GORDON (1936): Told in thirteen weekly installments, it was the first screen adventure for the comic-strip character Flash Gordon, and tells the story of his first visit to the planet Mongo and his encounter with the evil Emperor Ming The Merciless. Lawrence ‘Larry’ ‘Buster’ Crabbe played the central role in Flash Gordon which supposedly had a budget of over a million dollars, but was later revealed to be only around US$350,000. A lot of props and other elements were recycled from earlier Universal productions: The watchtower from Frankenstein (1931) appeared as Zarkov’s base; The Egyptian idol from The Mummy (1932) became the idol of the Great God Tao; Shots of Earth from space came from The Invisible Ray (1936); The rocket ships were reused from Just Imagine (1930); An entire dance sequence from The Midnight Sun (1927) was used; A laboratory set from The Bride Of Frankenstein (1935); Ming’s attack on Earth used newsreel footage; And the music was recycled from several other films.

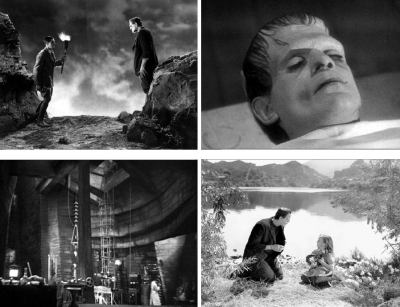

FRANKENSTEIN (1931): When viewed in its original censorship-free version, James Whale‘s Frankenstein and Boris Karloff‘s portrayal of the greatest monster of all-time, combine to deliver the definitive treatment of Mary Shelley‘s sympathetic tale. Whale’s film amplifies the torment of a man struggling with his feverish dreams of creating life and the agonising existence of his creation – a monster. Brought to life by the obsessed Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive), our gentle giant is tormented and ill-treated, not only by the scientist’s side-kick Fritz (Dwight Frye) but by his all-too-immediate role in society. Portrayed as the villain, Karloff brings humanity and empathy to the monster. In one of the most controversial scenes, we see the giant play like a bewildered child, throwing flowers into a lake with a young girl only to misunderstand and all too often misjudged by the society that created him, he is hunted as the savage killer he has become. Karloff’s greatest and most famous role, and perhaps the most fantastic use of monster makeup of all time ensure that James Whale’s Frankenstein remains the best of them all.

FRANKENSTEIN (1931): When viewed in its original censorship-free version, James Whale‘s Frankenstein and Boris Karloff‘s portrayal of the greatest monster of all-time, combine to deliver the definitive treatment of Mary Shelley‘s sympathetic tale. Whale’s film amplifies the torment of a man struggling with his feverish dreams of creating life and the agonising existence of his creation – a monster. Brought to life by the obsessed Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive), our gentle giant is tormented and ill-treated, not only by the scientist’s side-kick Fritz (Dwight Frye) but by his all-too-immediate role in society. Portrayed as the villain, Karloff brings humanity and empathy to the monster. In one of the most controversial scenes, we see the giant play like a bewildered child, throwing flowers into a lake with a young girl only to misunderstand and all too often misjudged by the society that created him, he is hunted as the savage killer he has become. Karloff’s greatest and most famous role, and perhaps the most fantastic use of monster makeup of all time ensure that James Whale’s Frankenstein remains the best of them all.

FREAKS (1932): Unusual for a Hollywood film, Tod Browning‘s Freaks was banned outright for many years. This was mainly because it uses circus freaks (real ones, including Siamese twins and several hydrocephalics, some of them deformed so grossly that it is difficult to imagine how they came to be alive at all, such as the man whose body stops at the base of his rib cage) to pose the simple question, “What is normal?” Cleopatra (Olga Baclanov) is an attractive normal-sized circus trapeze star who is worshiped by Hans (Harry Earles), a dwarf engaged to marry another midget (played by his real-life sister Daisy Earles). When the trapeze artist discovers that Hans is wealthy, she agrees to marry him, and later attempts to poison him. The circus freaks find out, and they take terrible revenge.

FREAKS (1932): Unusual for a Hollywood film, Tod Browning‘s Freaks was banned outright for many years. This was mainly because it uses circus freaks (real ones, including Siamese twins and several hydrocephalics, some of them deformed so grossly that it is difficult to imagine how they came to be alive at all, such as the man whose body stops at the base of his rib cage) to pose the simple question, “What is normal?” Cleopatra (Olga Baclanov) is an attractive normal-sized circus trapeze star who is worshiped by Hans (Harry Earles), a dwarf engaged to marry another midget (played by his real-life sister Daisy Earles). When the trapeze artist discovers that Hans is wealthy, she agrees to marry him, and later attempts to poison him. The circus freaks find out, and they take terrible revenge.

The story may be melodramatic, but it is triumphantly justified by the poignancy with which the film’s point is so succinctly made, that normality is in the eye of the beholder. It is the lovely trapeze artist and her strongman boyfriend who are psychologically abnormal, because they are affectless – that is to say, they do not have ordinary human feelings. In contrast, the freaks very quickly come to seem like ordinary people, except they are a little more vulnerable. This justifies Browning’s decision for which he was much criticised, to use real freaks. It is, in fact, a very humane movie and, oddly enough, it manages to make the freaks appear normal without either patronising or sentimentalising them.

THE INVISIBLE MAN (1933): Hats must be taken off to any film that boasts a lead role that you can’t see. Claude Rains‘ bandage-clad portrayal of The Invisible Man is unparalleled when it comes to invisible men. James Whale‘s version of the H.G. Wells classic remains the most iconic, blending science fiction, the supernatural, and groundbreaking special effects with sly black comedy and suspense. It should not be forgotten, however, that Claude Rains’ transparent role is pure evil, a man consumed by the desire to have the world groveling at his feet – a contemptuous being that wreaks havoc and thrives on mass destruction and anarchy. The only glimmer of humanity emerges in his love for Flora (Gloria Stuart), but this isn’t enough to prevent his inevitable self-destruction. He’s mad, he’s bad and he’s invisible! A true classic not to be missed. As the mad scientist Griffin, Claude Rains gives a memorable performance despite being heard but not seen for most of the film. In the early scenes his face is covered in bandages and it is not until he dies in the hospital that the audience receives a glimpse of him. For the rest of the film he is entirely invisible or represented by various articles of apparently empty clothing – shirt, trousers, dressing gown and so on.

ISLAND OF LOST SOULS (1933): Starring Charles Laughton and Bela Lugosi from a script co-written by science fiction legend Philip Wylie, the movie was the first film adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel The Island Of Doctor Moreau, and directed by Eric Kenton. Both book and movie are about a remote island that is run by an obsessed scientist who is secretly conducting surgical experiments on animals. The goal of these experiments is to try to transform the animals into human beings. The result of the experiments is a race of half-human, half-animal creatures that lives in the island’s jungles under Moreau’s tentative control. The film was refused a certificate three times by the British Film Censors – 1933, 1951, 1957 – due to scenes of vivisection. The film was eventually passed with an X Certificate in 1958. My old friend H.G. Wells was rather outspoken in his dislike of the film, feeling the overt horror elements overshadowed the story’s deeper philosophies. At least two films have since been made based on the same novel, the first released in 1977 starring Burt Lancaster and Michael York, the second was released in 1996 starring Marlon Brando as the mad but well-meaning Doctor Moreau. There was also the very similar Twilight People (1973) starring the sexy Pam Grier as the panther woman.

ISLAND OF LOST SOULS (1933): Starring Charles Laughton and Bela Lugosi from a script co-written by science fiction legend Philip Wylie, the movie was the first film adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel The Island Of Doctor Moreau, and directed by Eric Kenton. Both book and movie are about a remote island that is run by an obsessed scientist who is secretly conducting surgical experiments on animals. The goal of these experiments is to try to transform the animals into human beings. The result of the experiments is a race of half-human, half-animal creatures that lives in the island’s jungles under Moreau’s tentative control. The film was refused a certificate three times by the British Film Censors – 1933, 1951, 1957 – due to scenes of vivisection. The film was eventually passed with an X Certificate in 1958. My old friend H.G. Wells was rather outspoken in his dislike of the film, feeling the overt horror elements overshadowed the story’s deeper philosophies. At least two films have since been made based on the same novel, the first released in 1977 starring Burt Lancaster and Michael York, the second was released in 1996 starring Marlon Brando as the mad but well-meaning Doctor Moreau. There was also the very similar Twilight People (1973) starring the sexy Pam Grier as the panther woman.

KING KONG (1933): There were monsters before King Kong. The dinosaurs in The Lost World (1925), and the creature in Frankenstein (1931), but he was a deformed man rather than a beast. It was King Kong that set up a matrix for the monster genre in which many monster movies are molded even today. Much has been written about this film, and its epic story has been interpreted in many ways – sexually, politically and racially. It’s so full of striking imagery that it’s easy to see symbolic undertones in almost every frame. A popular film will often reflect contemporary attitudes and fears without its makers realising it – one interpretation is that King Kong represents the American black, a creature who is taken forcibly from his homeland to America where he is exploited in chains but then breaks free and conquers New York (every scene in New York corresponds to a scene on Skull Island), snarling his defiance at the world. Certainly many young American blacks identified with Kong and conversely the film reflected white America’s fear of the black man. Gorillas, as menacing creatures, had been featuring in American films since the early silent days, often in serials and in such films as The Unholy Three (1925 & 1930), The Murders In The Rue Morgue (1914 & 1932) and even Sign Of The Cross (1932). Usually at some point in the story, they threaten a beautiful white girl with ‘a fate worse than death’. King Kong takes this metaphor of sexual threat to its ultimate limit – the film is a treasure-trove of Freudian symbols.

KING KONG (1933): There were monsters before King Kong. The dinosaurs in The Lost World (1925), and the creature in Frankenstein (1931), but he was a deformed man rather than a beast. It was King Kong that set up a matrix for the monster genre in which many monster movies are molded even today. Much has been written about this film, and its epic story has been interpreted in many ways – sexually, politically and racially. It’s so full of striking imagery that it’s easy to see symbolic undertones in almost every frame. A popular film will often reflect contemporary attitudes and fears without its makers realising it – one interpretation is that King Kong represents the American black, a creature who is taken forcibly from his homeland to America where he is exploited in chains but then breaks free and conquers New York (every scene in New York corresponds to a scene on Skull Island), snarling his defiance at the world. Certainly many young American blacks identified with Kong and conversely the film reflected white America’s fear of the black man. Gorillas, as menacing creatures, had been featuring in American films since the early silent days, often in serials and in such films as The Unholy Three (1925 & 1930), The Murders In The Rue Morgue (1914 & 1932) and even Sign Of The Cross (1932). Usually at some point in the story, they threaten a beautiful white girl with ‘a fate worse than death’. King Kong takes this metaphor of sexual threat to its ultimate limit – the film is a treasure-trove of Freudian symbols.

L’AGE D’OR (1930): Horror News is not the place to embark on a lengthy definition of what precisely can or can’t be defined as surrealism. But the primary qualities of surrealism can all be found in one film, the first truly surrealist feature film, L’Âge d’Or, directed by Luis Buñuel. The surrealist painter Salvador Dali is given a co-writing credit but really had very little to do with the film, although he was a genuine co-writer on Buñuel’s first surrealist short film Un Chien Andalou (1929). L’Âge d’Or has its flaws, and it’s easy to find parts of it pretentious, but it must surely be one of the most important genre films ever made. All of these qualities of surrealism re-emerge again and again in genre cinema, firstly in consciously artistic films made for the intelligentsia, and later in commercial films, especially horror movies.

MAD LOVE (1935): An adaptation of the Maurice Renard story The Hands Of Orlac directed by German photographer Karl Freund (who changed his first name to Carl with a ‘C’ after relocating to the USA), starring Peter Lorre as Doctor Gogol and Colin Clive as Stephen Orlac. The plot revolves around Doctor Gogol’s obsession over actress Yvonne Orlac. When Stephen Orlac’s hands are destroyed in a train accident, Yvonne brings him to Gogol who says he is able repair them. As Gogol’s obsession over Yvonne leads him into doing anything to have her, Stephen Orlac finds that his new hands have made him into an expert knife thrower. Critics praised Lorre for his acting, but the film was unsuccessful at the box office. Though she found the film unsatisfactory, Pauline Kael drew parallels between Mad Love and Citizen Kane (1941), claiming much of the latter film’s visual style was borrowed from Mad Love, probably because cinematographer Gregg Toland was involved in the production of both films. Mad Love’s reputation has grown over the years and is now viewed in a more positive light by modern film critics.

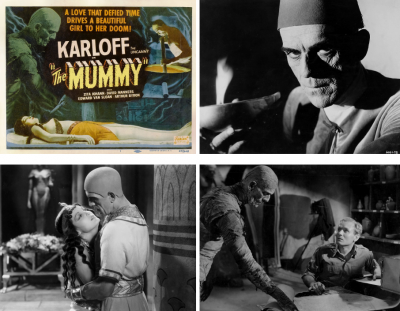

THE MUMMY (1932): It may not be as action-packed or as lavish as the 1999 Stephen Sommers remake starring Brendan Fraser and Arnold Vosloo, but the 1932 effort with monster-maestro Boris Karloff certainly deserves a place alongside Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931) in the Universal pantheon of timeless horror icons – but only just. Karloff again manages to bring to the screen an air of mesmerising eeriness and the effortless quality of captivating the viewer in his portrayal of the mummy Imhotep, searching for his reincarnated princess. Sadly, the film lacks any real suspense and all too often some absurd dialogue undermines this rather dull effort. Still, Jack Pierce‘s incredible makeup, Karloff’s indomitable presence and the popular topic of reincarnation justifies its place as a classic. Despite her faults, everybody still loves their Mummy.

THE MUMMY (1932): It may not be as action-packed or as lavish as the 1999 Stephen Sommers remake starring Brendan Fraser and Arnold Vosloo, but the 1932 effort with monster-maestro Boris Karloff certainly deserves a place alongside Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931) in the Universal pantheon of timeless horror icons – but only just. Karloff again manages to bring to the screen an air of mesmerising eeriness and the effortless quality of captivating the viewer in his portrayal of the mummy Imhotep, searching for his reincarnated princess. Sadly, the film lacks any real suspense and all too often some absurd dialogue undermines this rather dull effort. Still, Jack Pierce‘s incredible makeup, Karloff’s indomitable presence and the popular topic of reincarnation justifies its place as a classic. Despite her faults, everybody still loves their Mummy.

THINGS TO COME (1936): Directed by William Cameron Menzies from a screenplay by my old friend H.G. Wells, Things To Come is a rather loose adaptation of his own 1933 novel, a true landmark in cinematic design as well as predicting World War Two, being only about a year off by having it start December 1940 instead of September 1939. Its graphic depiction of strategic bombing in the scenes in which Everytown is flattened by air attack and society collapses into barbarism, echo pre-war concerns about the threat of the bomber and the apocalyptic pronouncements of air-power prophets. H.G. was also an air-power prophet of sorts, having described aerial warfare in Anticipations and War In The Air. The use of gas bombs is very much part of the film, from the poison gas used early in the war to the sleeping gas used by the airmen of Wings Over The World. In real life, in the build-up to World War Two, there was much concern that the Germans would use poison gas, which was used by France, Germany and Great Britain during World War One. Civilians were required to carry Gas Masks and were trained in their use. When war did break out, however, the Germans did not use gas for military purposes. The fictional organisation Wings Over The World is based in southern Iraq (the so-called cradle of civilisation) from where it begins a new civilisation. The one-world government having engineers, scientists and inventors as the rulers mimics the ideology of the concept of Technocracy where those of the greatest skill and intellect in various vocations would be the leaders.

VAMPYR (1932): Directed by Carl Dreyer and inspired by elements of J. Sheridan Le Fanu‘s collection of supernatural stories entitled In A Glass Darkly, Vampyr was funded by Nicolas de Gunzburg who starred in the film under the name of Julian West among a mostly non-professional cast. Gunzberg plays the role of Allan Grey, a student of the occult who enters the village of Courtempierre, which is under the curse of a vampire. the film was challenging for Dreyer to make as it was his first ‘talkie’ and had to be recorded in three different languages. To overcome this, very little dialogue was used in the film and much of the story is told with title cards. The audio editing was done in Berlin where the voices, sound effects and music were added to the film. Vampyr had a delayed release in Germany and opened to a generally negative reception from audiences and critics. The film was considered by many as a low point in Dreyer’s career, but modern critical reception has become much more favourable with critics praising the film’s disorienting visual effects and atmosphere. Vampyr isn’t the easiest classic film to enjoy, even if you are a fan of vintage horror movies but, if you’re patient with the slow pacing and ambiguous story line, you’ll find that this film offers many striking images. The greatness of the film derives partly from its handling of the vampire theme in terms of sexuality and eroticism and partly from its highly distinctive dreamy look, but it also has something to do with Dreyer’s radical recasting of narrative form. A triumph of the irrational, this eerie effort never allows either protagonist or viewer to fully wake-up from its surreal nightmare.

WHITE ZOMBIE (1932): I must hasten to point out, these zombies are not the flesh-eating variety. Since Night Of The Living Dead (1968), their official job description now includes an insatiable appetite for brains, and in some recent films have even become champion sprinters!

WHITE ZOMBIE (1932): I must hasten to point out, these zombies are not the flesh-eating variety. Since Night Of The Living Dead (1968), their official job description now includes an insatiable appetite for brains, and in some recent films have even become champion sprinters!

White Zombie has good performances, excellent photography, thoughtful music, some nice glass paintings, a dream-like atmosphere, huge rooms which resemble the cavernous interiors in Doctor Frankenstein’s ancestral home, and an attractive zombie named Madeline, who retains her ability to play the piano after brain-death. That’s more than Ozzy Osborne could manage! White Zombie was directed by Victor Halperin, and I suspect it to be his career high-point. He directed other films in the same genre, including Supernatural (1933) and Revolt Of The Zombies (1936). Supernatural is well-worth a look, and Revolt Of The Zombies is…is a terrible waste of a good title. In White Zombie he was at his most inspired.

THE WIZARD OF OZ (1939): Directed primarily by Victor Fleming from a script by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf, with uncredited contributions by many others. Notable for its use of special effects, Technicolor, fantasy and unusual characters, The Wizard Of Oz has become one of the best-known of all films and a true classic. However, although it received largely positive reviews and won three Oscars, the film was initially considered a box-office failure.

It was MGM’s most expensive production up to that time, which explains why the studio was unable to recoup its initial investment when it was first released, but it made up for that in subsequent re-releases. Somewhere Over The Rainbow won Best Original Song Oscar and the film itself received several nominations, including Best Picture. Television screenings began in 1956 and, because of them the film has found a larger audience, its television screenings were once an annual tradition and have re-introduced the film to the public, making The Wizard Of Oz one of the most famous films ever made, in fact the Library Of Congress named The Wizard Of Oz as the most watched film in history.

Also: see

1920s Genre Films

1940s Genre Films

1950s Genre Films

1960s Genre Films

1970s Genre Films

1980s Genre Films

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews