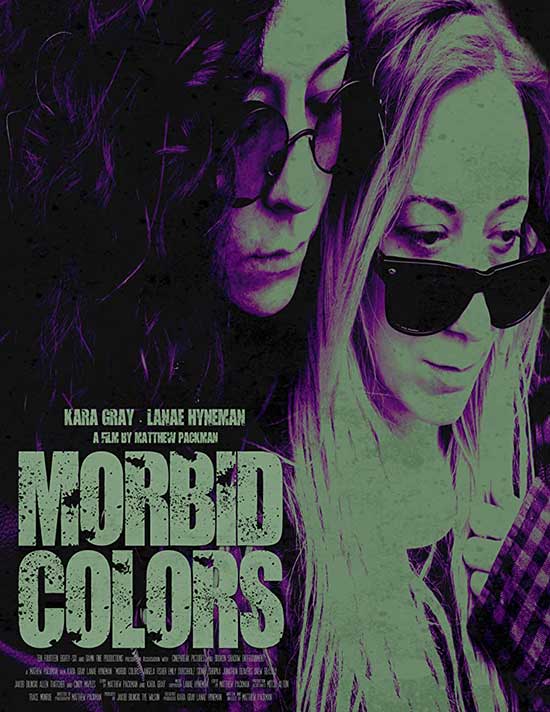

SYNOPSIS:

A tale of two foster sisters forced to hunt down a wealthy socialite believed to have infected the elder sibling with vampirism.

REVIEW:

There are the cinema entries in the horror realm that offer hope in the darkness. There are those that lean heavily toward the bleak and unrelenting aura. There are even genre efforts where the balance of positive-negative is on a level of equal precision not seen outside of a chemistry lab. Then there is a work such as Matthew Packman’s Morbid Colors, a tale of vampirism as psycho-sexual addiction involving characters that seem a mix of garage punk with central character traits from John Ajvide Lindqvist’s 2004 Swedish vampire novel Låt den rätte komma in (Let the Right One In).

I mention the latter because, as I watched the lives of foster sisters Devin and Myca (the main characters in Colors) as they deal with the latter’s blood-sucking addiction and finding their biological mom and the answers to Myca’s affliction, I couldn’t help but recall the core duo of Oskar and Eli from Lindqvist’s story. There is a connecting thread of loneliness amongst the societal outer fringe. The human beings forgotten by most of civilization. Lindqvist uses bullying to beat Oskar into the morbidity realm he finds himself in (studying forensic science and such) when he meets the vampiric Eli and forms a friendship with. While Devin and Myca in Morbid Colors have a different set of torments (child abuse, rape, a broken foster care system, and a drug-addicted mom) to bullying, there is a familiarity in the close bond of friendship that is almost more powerful than vampirism or any other addiction.

I’d been a fan of Packman and his study of the complexities of relationships under the duress of an extreme environment since I first saw the 2016 post-apocalyptic drama thriller Margo and had long wondered where his alienated character studies theme would take him next. Lo and behold, he dives right a cinema of the bizarre storyline that pops even as the blood oozes frequently. Even the title catches the viewing eye and suggests a fresh duality of perspective is in store for the viewer jaded going in by the familiar. The colors that are metaphors for the stark reminders of nihilism, bleakness and, indeed, death are on display (black, blue and lots of crimson-hued gore on full view).

Yet there is also a subtext that suggests the absence of color in describing the darkened areas of the human psyche and the strong desire to surface out into a brighter world of vibrance away from the dank. Myca, like Oskar earlier, feels like abuse and torment have ripped the opportunity for happiness from her, and she lurches forward on a desperate search to find a way out. It seems to matter little to her whether the end result of her search will be death or continued life. Release from her current world makes it a happy ending either way.

Packman, a relative newcomer still to directing, makes a move that not even some veteran filmers think of and that is to opt for minimalism of dialogue where possible in this picture. The climax of the picture, as the heroine pair close in their biological mom and answers to key questions in the mother’s house, is a prime example of body language, deliberately static camera shots and facial expression communicating the emotion and undercurrent of a scene better than dialogue ever could. It’s refreshing that the filmmaking art of displaying a life story within a human face is not lost in these days of cartoons and cgi.

The cast more than delivers for Packman here. I was suitably impressed with both Kara Gray as Myca and Lanae Hyneman as Devin. Gray shows the ravages of her character’s obsession for blood putting her into near-helpless resignation to the urge (not unlike a heroin addict in the stage of time before their next fix). Devin has her own battle that is overwhelming her into her own emotional coma-ish state, the need for friendship/companionship against the revulsion she feels growing to the bloodletting carnage her foster sibling is causing.

I suppose I’ve had a fascination with the psychological compulsion angle of blood consumption and vampirism as a young chiller fan going back to when I first saw George Romero’s pioneering take on the subject in Martin 1978.

Though I am not amongst the 50,000 folks that psychiatrists Richard L. Vanden Bergh and John F. Kelley claimed were obsessed with blood-drinking (their study Vampirism: a Review with New Observations was published in 1964 in the Archives of General Psychiatry), I am very much intrigued when the subject is touched on in celluloid. Morbid Colors does that in most gripping fashion, giving an unflinching eye view of the power that addiction to anything (blood or otherwise) has in both eroding the human soul as well as obliterating hope. Gives one something new to think about should they find themselves with the odd fantasy about wanting to be a vampire after seeing the sexy stud-like undead in tv series like True Blood!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews