A self-assured business man murders his employer, the husband of his mistress, which unintentionally provokes an ill-fated chain of events.

REVIEW:

“Without your voice, I’d be lost in a land of silence.”

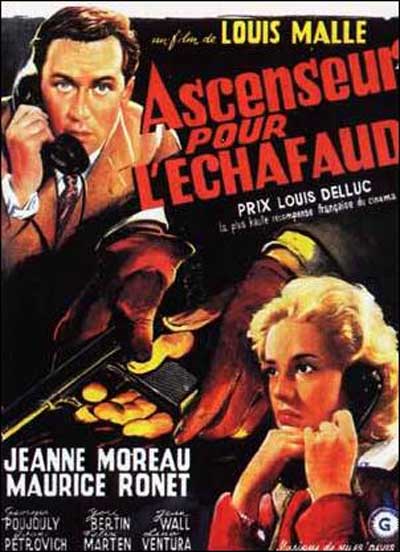

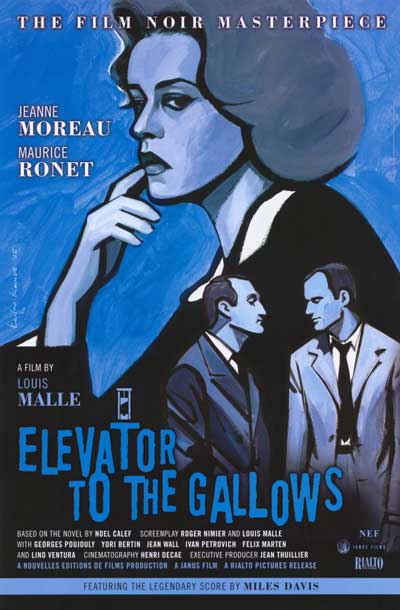

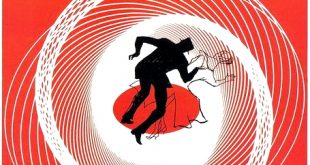

Ascenseur pour l’echafaud was Louis Malle’s debut film and certainly one of the strongest cinematic inaugurations of the medium. Typically, a filmmaker’s first feature film is his most representative, if not his most accomplished. Malle, however, was of that rare breed who defied this stereotype and excelled in his self-indulgence (Polanski, Welles, Tarkovsky, Truffaut, Lynch, Huston are a few others). Malle’s cinematographer for this film was Henri Decae, one of the early visual pioneers of, what would later become recognised as, French noir (Decae would work with Truffaut and Melville in the near future). However, the genre was an international product, with a European and American exchange of influences similar to the Western / Chanbara dynamic of America and Japan (Ford and Kurosawa). A common theme of the noir film is the self-deceiving protagonist who, under the guise of freewill, hurtles towards what he later interprets as predetermined fate. Often, the argumentative irony being that this fate is the indirect result of the character’s own choices.

A war veteran, Julien Tavernier (Maurice Ronet), plans to murder his boss, Mr. Carala (Jean Wall). Its closing time on a Saturday and Tavernier asks the receptionist to stay while he finishes up some business. As she sharpens pencils, he enters his office and locks the door. With revolver in pocket, he uses a grappling hook to climb from the balustrade outside to the foyer of Carala’s office. He enters the office wearing gloves and holding a business proposal, “Project Pipeline.” Carala has been waiting; he is late for his train. Tavernier is an anxious ball of determination as he offers the proposal. “Don’t sneer at war … it’s your family heirloom,” he says to him and Carala sees the pistol. The shot goes unheard as the receptionist sharpens pencils. Tavernier returns back to his office, the deed done, Carala’s murder staged to look like suicide. He and the receptionist leave the building.

Tavernier is recognized by Veronique, a local flower seller, as he gets in his car. Tavernier’s scheme is thorough, his execution precise, until he spies the grappling hook dangling from Carala’s office railing. He carelessly leaves all his belongings in the car and sneaks back inside the building. He grabs the evidence and, as he takes the elevator back to ground level, the guard shuts off the power and locks up the building for the weekend.

Mr. Carala’s wife, Florence (Jeanne Moreau), is waiting for Tavernier at the Royal Cameo Café (as per usual). She is aware of his plan. In fact, they are lovers. While Tavernier is trapped between floors, Veronique, cajoled by her friend, Louis (an amateur thief), take the man’s car for a joyride.

They pass Florence who only sees the girl in the passenger seat and thinks the worst. There are sequences of Florence wandering empty Parisian streets, beautifully and naturally lit, inwardly lamenting Tavernier’s betrayal. Meanwhile, the youths check into a motel under the name of “Mr. and Mrs. Julien Tavernier” and end up murdering a couple of German tourists, leaving behind Tavernier’s car and pistol in the wake of their escape. The bodies of the tourists are discovered the next morning and Tavernier is sought after by the police. The plot is certainly “Hitchcockian,” but Malle’s treatment is subdued, more willing to explore the timeless freedom these characters spend in utter distress than, purely thrills and intrigue.

The excellent score by Miles Davis (a soundtrack worth picking up, jazz aficionado or not) heightens the unpredictability of the plot with freeform jazz quips and grooves while, at its core, provides one of cinema’s most pensive musical themes: a majestically remote trumpet. Indeed, much of the film is groundbreaking, not only in its juxtaposition of sight and sound but, in the angular editing style, serrated narrative, and of course the film’s influence on the noir genre.

Rating: A-

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews