SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

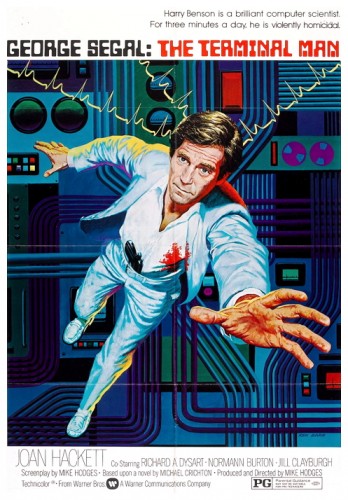

“As the result of a head injury, brilliant computer scientist Harry Benson begins to experience violent seizures. In an attempt to control the seizures, Benson undergoes a new surgical procedure in which a microcomputer is inserted into his brain. The procedure is not entirely successful.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Best-selling author, filmmaker and physician Michael Crichton passed away in 2008, and was best known for his science fiction thrillers. His novels have sold over 200 million copies worldwide, many made into movies, in fact Crichton became the only creative artist ever to have works simultaneously ranked #1 in American television, novel and film sales with ER, Disclosure and Jurassic Park (1993), respectively. Other films adapted from his writings include The Andromeda Strain (1971), Dealing (1972), The Carey Treatment (1972), Westworld (1973), The First Great Train Robbery (1979), Looker (1981), Runaway (1984), Rising Sun (1993), Disclosure (1994), Congo (1995), Twister (1996), Jurassic Park The Lost World (1997), Sphere (1998), The Thirteenth Warrior (1999) and Timeline (2003).

His novels were mostly techno-thrillers, often exploring new technologies and the failures of human interaction with it, usually resulting in catastrophes with bio-technology. Crichton published two novels in 1972: The first was Binary, about a villainous middle-class businessman who attempts to assassinate the President of the United States by stealing a military shipment of chemicals to concoct a deadly nerve gas. The second was The Terminal Man, about a psychomotor epileptic sufferer named Harry Benson, who regularly suffers from seizures followed by blackouts. He conducts himself ‘inappropriately’ during these seizures, waking up hours later with no knowledge of what he has done. Tiny terminals (the pun of the title) are implanted in his brain to control the seizures but not all goes to plan, reflecting Crichton’s continuing preoccupation with machine-human interaction.

His novels were mostly techno-thrillers, often exploring new technologies and the failures of human interaction with it, usually resulting in catastrophes with bio-technology. Crichton published two novels in 1972: The first was Binary, about a villainous middle-class businessman who attempts to assassinate the President of the United States by stealing a military shipment of chemicals to concoct a deadly nerve gas. The second was The Terminal Man, about a psychomotor epileptic sufferer named Harry Benson, who regularly suffers from seizures followed by blackouts. He conducts himself ‘inappropriately’ during these seizures, waking up hours later with no knowledge of what he has done. Tiny terminals (the pun of the title) are implanted in his brain to control the seizures but not all goes to plan, reflecting Crichton’s continuing preoccupation with machine-human interaction.

The theme of Crichton’s novel, which was filmed as The Terminal Man (1974), concerns a man who is turned into a machine. Unfortunately Crichton himself wasn’t involved with the direction nor the screenplay this time around. In fact Crichton was originally going to write and direct the film, but was fired because his script did not follow the novel (which he had written) closely enough. Instead it was written and directed by British filmmaker Mike Hodges, whose most famous efforts include Get Carter (1971) and Pulp (1972). Hodges was certainly very adept at making gritty off-beat thrillers, but his understanding of science fiction was less certain and Crichton’s basic theme gets lost along the way. Hodges’ obvious uncertainty in the genre can be witnessed in his other science fiction films Flash Gordon (1980) and Morons From Outer Space (1985).

The theme of Crichton’s novel, which was filmed as The Terminal Man (1974), concerns a man who is turned into a machine. Unfortunately Crichton himself wasn’t involved with the direction nor the screenplay this time around. In fact Crichton was originally going to write and direct the film, but was fired because his script did not follow the novel (which he had written) closely enough. Instead it was written and directed by British filmmaker Mike Hodges, whose most famous efforts include Get Carter (1971) and Pulp (1972). Hodges was certainly very adept at making gritty off-beat thrillers, but his understanding of science fiction was less certain and Crichton’s basic theme gets lost along the way. Hodges’ obvious uncertainty in the genre can be witnessed in his other science fiction films Flash Gordon (1980) and Morons From Outer Space (1985).

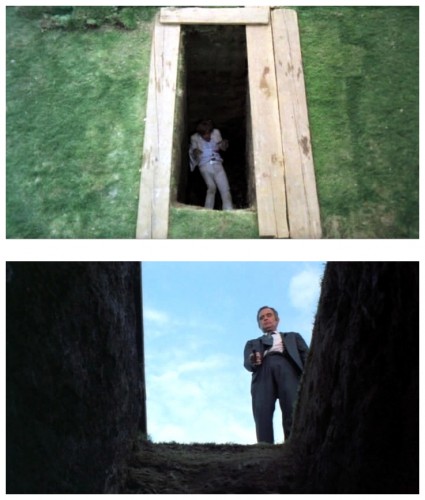

George Segal stars as computer specialist Harry Benson who suffers from violent blackouts as a result of brain damage sustained in a car accident. As his condition cannot be controlled by drugs, it is decided to insert a number of tiny electrodes into his brain, linked to a small computer surgically implanted into his shoulder which measure brain rhythms and initiate a calming effect when they become erratic. The idea is that when one of his seizures begins, the computer will send soothing impulses into his brain and thus prevent the blackout from occurring. In practice his brain enjoys the soothing effect so much that it induces the blackouts to occur at an ever-increasing rate, causing Benson to escape from the hospital and go on a rampage of violence. After committing some mayhem, he is chased by the authorities through a cemetery and finally shot down like a dog.

One of the best and most disturbing sequences in the film is when the technicians coolly test the implanted electrodes by stimulating various areas in Benson’s brain by remote control, causing him to experience pain, fear, pleasure, hunger and lust at the mere touch of a button. Not forgetting that Benson is an extremely intelligent (an IQ of 144 we are told) computer programmer who has developed an irrational fear of machines now finds himself being controlled by computers, but these chilling implications aren’t followed up, because Hodges is more anxious to concentrate on the thriller aspects of the story. Once Benson escapes from the hospital, the film degenerates into yet another murderer-on-the-loose movie. It’s certainly stylish and entertaining, even exciting at times but, like Crichton’s Westworld (1973) the year before, it simply fails to deliver what it promises. It was a box-office flop in America and was never actually seen in the United Kingdom until its VHS release in the eighties.

One of the best and most disturbing sequences in the film is when the technicians coolly test the implanted electrodes by stimulating various areas in Benson’s brain by remote control, causing him to experience pain, fear, pleasure, hunger and lust at the mere touch of a button. Not forgetting that Benson is an extremely intelligent (an IQ of 144 we are told) computer programmer who has developed an irrational fear of machines now finds himself being controlled by computers, but these chilling implications aren’t followed up, because Hodges is more anxious to concentrate on the thriller aspects of the story. Once Benson escapes from the hospital, the film degenerates into yet another murderer-on-the-loose movie. It’s certainly stylish and entertaining, even exciting at times but, like Crichton’s Westworld (1973) the year before, it simply fails to deliver what it promises. It was a box-office flop in America and was never actually seen in the United Kingdom until its VHS release in the eighties.

For good reason, some might say. An impressive supporting cast (Richard Dysart, Donald Moffatt, Michael Gwynne, Jill Clayburgh, James Sikking, Ian Wolfe, Robert Ito) offer extremely restrained, understated performances and, despite its obvious aspirations to some kind of artistry (music by Johann Sebastian Bach, a long quotation from The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot, etc.) the film is rather crude: The unfeeling doctors are purposely painted with the same brush and visual symbolism is used like a sledgehammer; the gleaming antiseptic sets appear distinctly hostile to organic life; doctors and orderlies loom menacingly presented as narcissistic vulgarians; uniforms indicate profession as a single letter on the collar (‘D’ for doctor, ‘N’ for nurse, ‘T’ for technician) and are very depersonalised in style; only dissenting staff like Doctor Ezra Manon (William Hansen) and Doctor Janet Ross (Joan Hackett) showing any hint of individuality in their work apparel.

The symbolism backfires, however, because it is difficult to feel sympathy for an experimental guinea pig who is pictured so coldly that we can have no interest in him as a person. Segal is given a few lines to speak that might humanise his character (that he is a mildly tormented ‘thing’ and his fate is of little interest) but director Hodges makes his point so heavy-handedly that the ship sinks under the weight. Similar comments could be made about a later film, Coma (1977), though this time the roles were reversed. Michael Crichton was now the director, and the film was based on a best-seller by another author, Robin Cook, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me again next week when I have the opportunity to scoop out your brain and drop it in a bucket with another spine-tingling journey to the dark side of…Horror News! Toodles!

The symbolism backfires, however, because it is difficult to feel sympathy for an experimental guinea pig who is pictured so coldly that we can have no interest in him as a person. Segal is given a few lines to speak that might humanise his character (that he is a mildly tormented ‘thing’ and his fate is of little interest) but director Hodges makes his point so heavy-handedly that the ship sinks under the weight. Similar comments could be made about a later film, Coma (1977), though this time the roles were reversed. Michael Crichton was now the director, and the film was based on a best-seller by another author, Robin Cook, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me again next week when I have the opportunity to scoop out your brain and drop it in a bucket with another spine-tingling journey to the dark side of…Horror News! Toodles!

The Terminal Man (1974)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews