SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Professor Moriarity has a scheme for stealing the crown jewels from the Tower of London. To get Holmes involved, he persuades a gaucho flute player to murder a girl.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

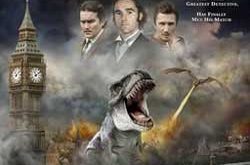

The Hound Of The Baskervilles (1939), based on the novel by Arthur Conan Doyle, was directed by Sidney Lanfield and produced by 20th Century Fox studios. Starring Basil Rathbone as the world’s greatest detective Sherlock Holmes and Nigel Bruce as his faithful biographer Doctor Watson, it’s probably the best-known cinematic adaptation of the book, and is regarded by many as one of the best of the Holmes films ever. For whatever motive millions of moviegoers had for going to see The Hound Of The Baskervilles, see it they did and made it one of the most successful films that year. The film was also a triumph for Rathbone. “He is the ideal selection for Holmes,” commented one critic and, although not all critics were convinced of this, the public were unanimous in applauding the Rathbone interpretation.

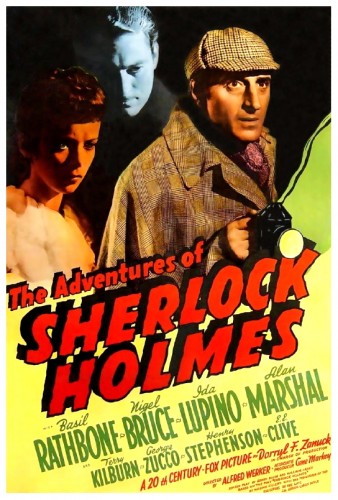

Because of the film’s success, 20th Century Fox hurried a sequel into production that very same year: The Adventures Of Sherlock Holmes (1939), and this time Rathbone and Bruce got the top billing they deserved. This new production was supposedly based on the William Gillette stage play, but the final product bears little resemblance to it, nor to the two other previous films which had supposedly used the play as their source. Screenplay writers Edwin Blum and William Drake added much new material and rejected a lot including (thank goodness) Holmes’ romantic entanglement. The main similarity between this film and the play was the high-pitched battle of wits between Holmes and Professor Moriarty (George Zucco).

Because of the film’s success, 20th Century Fox hurried a sequel into production that very same year: The Adventures Of Sherlock Holmes (1939), and this time Rathbone and Bruce got the top billing they deserved. This new production was supposedly based on the William Gillette stage play, but the final product bears little resemblance to it, nor to the two other previous films which had supposedly used the play as their source. Screenplay writers Edwin Blum and William Drake added much new material and rejected a lot including (thank goodness) Holmes’ romantic entanglement. The main similarity between this film and the play was the high-pitched battle of wits between Holmes and Professor Moriarty (George Zucco).

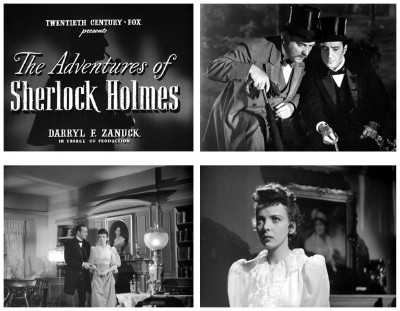

The plot, with its complicated convolutions, deals with Moriarty’s attempt to commit the most incredible crime of the century, the theft of the Crown Jewels. He attempts to blind Holmes to his machinations by providing a bizarre problem to occupy his mind. He tells one of his minions, “I am depending on it to absorb Mister Holmes’ interest, while I am engaged elsewhere. I’ll give him a toy to delight his heart, so full of bizarre complications that he’ll become completely involved.” The ‘toy’ is revealed to Holmes when he is visited in his Baker Street rooms by Ann Brandon (Ida Lupino) who is almost on the verge of hysterics. Her brother Lloyd has received a grotesque note – the drawing of a man with a strange bird hanging round his neck – exactly like a warning note which preceded her father’s brutal death ten years earlier.

The plot, with its complicated convolutions, deals with Moriarty’s attempt to commit the most incredible crime of the century, the theft of the Crown Jewels. He attempts to blind Holmes to his machinations by providing a bizarre problem to occupy his mind. He tells one of his minions, “I am depending on it to absorb Mister Holmes’ interest, while I am engaged elsewhere. I’ll give him a toy to delight his heart, so full of bizarre complications that he’ll become completely involved.” The ‘toy’ is revealed to Holmes when he is visited in his Baker Street rooms by Ann Brandon (Ida Lupino) who is almost on the verge of hysterics. Her brother Lloyd has received a grotesque note – the drawing of a man with a strange bird hanging round his neck – exactly like a warning note which preceded her father’s brutal death ten years earlier.

Holmes immediately tackles the problem and, while he sends Watson off to spy on Miss Brandon’s suspicious fiance, he visits the Kensington Museum where he determines the strange bird to be an albatross: “This is no childish prank, Miss Brandon, but a cryptic warning of avenging death. We must go to your brother at once!” Unfortunately Holmes is too late, Lloyd Brandon is found murdered in the street. He deduces the weapon used is a weird one which first strangles and then crushes the skull. From then on Holmes becomes deeply involved with the Brandon affair, as Moriarty hoped, and neglects a threat to the safety of a precious stone – The Star Of Delhi – as a trivial matter. As a result, Watson substitutes for Holmes while the diamond is transported to the Tower of London for safekeeping.

Holmes immediately tackles the problem and, while he sends Watson off to spy on Miss Brandon’s suspicious fiance, he visits the Kensington Museum where he determines the strange bird to be an albatross: “This is no childish prank, Miss Brandon, but a cryptic warning of avenging death. We must go to your brother at once!” Unfortunately Holmes is too late, Lloyd Brandon is found murdered in the street. He deduces the weapon used is a weird one which first strangles and then crushes the skull. From then on Holmes becomes deeply involved with the Brandon affair, as Moriarty hoped, and neglects a threat to the safety of a precious stone – The Star Of Delhi – as a trivial matter. As a result, Watson substitutes for Holmes while the diamond is transported to the Tower of London for safekeeping.

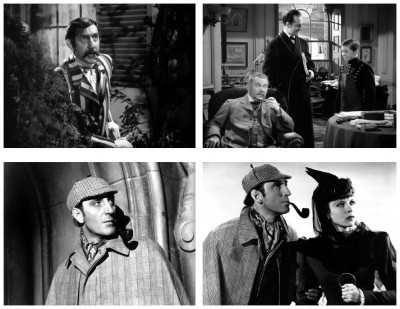

Meanwhile Holmes, in one of his most successful disguises as a music hall entertainer, attends a garden party where he believes an attempt will be made on Ann Brandon’s life – he is correct. Hearing her cries from a nearby park, Holmes rushes to the spot just as a dim figure is about to hurl a Patagonian bolas, a weapon consisting of three long strands of rawhide each tipped with leather-coated lead balls. Holmes knocks Ann to the ground and the bolas winds itself around a statue, snapping off its head. Holmes shoots the fleeing assailant and wounds him. He is captured and admits he is one Gabriel Mateo whose father was murdered by Ann’s father who had stolen his South American mine. Mateo also reveals that it is Moriarty who has urged him to seek revenge. Holmes then realises that Moriarty has used these crimes to shield a greater one.

Meanwhile Holmes, in one of his most successful disguises as a music hall entertainer, attends a garden party where he believes an attempt will be made on Ann Brandon’s life – he is correct. Hearing her cries from a nearby park, Holmes rushes to the spot just as a dim figure is about to hurl a Patagonian bolas, a weapon consisting of three long strands of rawhide each tipped with leather-coated lead balls. Holmes knocks Ann to the ground and the bolas winds itself around a statue, snapping off its head. Holmes shoots the fleeing assailant and wounds him. He is captured and admits he is one Gabriel Mateo whose father was murdered by Ann’s father who had stolen his South American mine. Mateo also reveals that it is Moriarty who has urged him to seek revenge. Holmes then realises that Moriarty has used these crimes to shield a greater one.

In something of an anti-climax, the detective hurries to the Tower of London where he is just in time to prevent Moriarty stealing the Crown Jewels. After a struggle on the top of the Tower, a blow from Holmes causes the master criminal to fall to what we must presume to be his death. Despite the screenplay’s shortcomings – how Moriarty knew the exact Inca funeral dirge Ann Brandon had heard before her father’s death is never explained, nor is it clear how he came to know of the cryptic significance of the albatross – the film maintains the high standard that The Hound Of The Baskervilles had set and, in may respects, it is a better film. Alfred Werker was a fine director and he set the action at an exciting pace, while making full use of 20th Century Fox’s impressive London sets, creating an authentic period atmosphere. We are treated to some superb vignettes, such as the thrilling scene involving the killer garbed in a South American gaucho outfit, with close-ups of his grotesque club foot moving slowly and deliberately in pursuit of the heroine through the fog-shrouded park at night.

In something of an anti-climax, the detective hurries to the Tower of London where he is just in time to prevent Moriarty stealing the Crown Jewels. After a struggle on the top of the Tower, a blow from Holmes causes the master criminal to fall to what we must presume to be his death. Despite the screenplay’s shortcomings – how Moriarty knew the exact Inca funeral dirge Ann Brandon had heard before her father’s death is never explained, nor is it clear how he came to know of the cryptic significance of the albatross – the film maintains the high standard that The Hound Of The Baskervilles had set and, in may respects, it is a better film. Alfred Werker was a fine director and he set the action at an exciting pace, while making full use of 20th Century Fox’s impressive London sets, creating an authentic period atmosphere. We are treated to some superb vignettes, such as the thrilling scene involving the killer garbed in a South American gaucho outfit, with close-ups of his grotesque club foot moving slowly and deliberately in pursuit of the heroine through the fog-shrouded park at night.

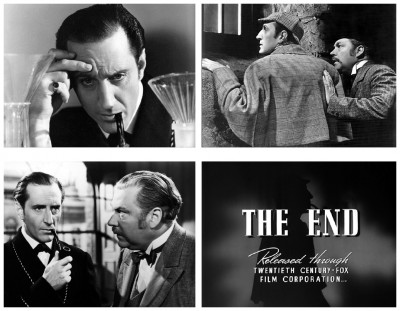

In general the film was well-received, although many reviewers thought there were too many loose ends for complete credulity, and one perceptive American critic made the observation that even the English climate seldom has such thick fogs in May. Moriarty was played with all the supercilious truculence the role requires by George Zucco, a British actor who made a career of playing villains in Hollywood features during the thirties and forties. In fact he was to pit his wits against Rathbone’s on a later occasion, in Sherlock Holmes In Washington (1943). Zucco made Moriarty a suave and smug character who obviously enjoyed doing evil for evil’s sake. The ultimate purpose behind his machinations was to defeat his arch-enemy. A minion asks Moriarty, “Holmes again?” – “Always Holmes…until the end!”

In general the film was well-received, although many reviewers thought there were too many loose ends for complete credulity, and one perceptive American critic made the observation that even the English climate seldom has such thick fogs in May. Moriarty was played with all the supercilious truculence the role requires by George Zucco, a British actor who made a career of playing villains in Hollywood features during the thirties and forties. In fact he was to pit his wits against Rathbone’s on a later occasion, in Sherlock Holmes In Washington (1943). Zucco made Moriarty a suave and smug character who obviously enjoyed doing evil for evil’s sake. The ultimate purpose behind his machinations was to defeat his arch-enemy. A minion asks Moriarty, “Holmes again?” – “Always Holmes…until the end!”

When the two antagonists appear together on screen (which is all too infrequent) the dialogue fairly bristles, like near the beginning of the film, just after Moriarty has been found Not Guilty of a murder charge owing to lack of evidence, he and Holmes meet outside the courthouse: “You’ve a magnificent brain, Moriarty, I admire it. I admire it so much I’d like to present it pickled in alcohol to the London Medical Society!” The rest of the dialogue does not quite come up to this level but nevertheless there is an air of Holmesian authenticity about it, like when the detective discusses the murder of Ann’s brother: “Brandon was strangled to death. The wounds on the back of the head were administered post-mortem, which introduces an interesting element – they were unnecessary therefore vicious. Intelligent criminals are seldom vicious and, though the apparent method of the crime was brutal, I am convinced the crime itself was intelligently planned!” Conan Doyle himself would surely not have been ashamed of that exposition.

When the two antagonists appear together on screen (which is all too infrequent) the dialogue fairly bristles, like near the beginning of the film, just after Moriarty has been found Not Guilty of a murder charge owing to lack of evidence, he and Holmes meet outside the courthouse: “You’ve a magnificent brain, Moriarty, I admire it. I admire it so much I’d like to present it pickled in alcohol to the London Medical Society!” The rest of the dialogue does not quite come up to this level but nevertheless there is an air of Holmesian authenticity about it, like when the detective discusses the murder of Ann’s brother: “Brandon was strangled to death. The wounds on the back of the head were administered post-mortem, which introduces an interesting element – they were unnecessary therefore vicious. Intelligent criminals are seldom vicious and, though the apparent method of the crime was brutal, I am convinced the crime itself was intelligently planned!” Conan Doyle himself would surely not have been ashamed of that exposition.

Nigel Bruce‘s Watson was, as before, no fit companion (one might think) for the intellectually brilliant Holmes, but a likable buffoon of a man nonetheless. Rathbone was again excellent. His timing and phrasing seemed to echo the Holmes of Conan Doyle’s pages, while cutting a figure reminiscent of the original Sidney Paget illustrations. Rathbone was never again to achieve this peak of performance, later a certain tiredness with the character made him exaggerate Holmes’ idiosyncrasies to the detriment of his portrayal. Also, sadly, it was the last time Rathbone was to play the detective in period. He was never again to stride through the fog in his inverness cape and deerstalker hat. But, in regards to the quantity of films, Rathbone’s career as the world’s greatest detective had hardly begun.

Nigel Bruce‘s Watson was, as before, no fit companion (one might think) for the intellectually brilliant Holmes, but a likable buffoon of a man nonetheless. Rathbone was again excellent. His timing and phrasing seemed to echo the Holmes of Conan Doyle’s pages, while cutting a figure reminiscent of the original Sidney Paget illustrations. Rathbone was never again to achieve this peak of performance, later a certain tiredness with the character made him exaggerate Holmes’ idiosyncrasies to the detriment of his portrayal. Also, sadly, it was the last time Rathbone was to play the detective in period. He was never again to stride through the fog in his inverness cape and deerstalker hat. But, in regards to the quantity of films, Rathbone’s career as the world’s greatest detective had hardly begun.

The quality of the two 20th Century Fox films was such that under ordinary circumstances a franchise would be a foregone conclusion but, by the end of 1939, the Second World War had broken out and foreign agents and spies were much more typical and topical than the antiquated criminal activities of Moriarty and his ilk. 20th Century Fox saw the Holmes series as too dubious a commercial proposition to continue on the same level of high-budget production and too difficult to relegate to their B-grade film series, so Fox dropped Sherlock Holmes. In 1942 Universal Pictures acquired the screen rights from the Conan Doyle estate and immediately put Rathbone and Bruce under contract for a dozen Holmes films, thus one studio was continuing a franchise originated by another using the same lead actors, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me again next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier with another feather from that cinematic ugly duckling known as Horrorwoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

The quality of the two 20th Century Fox films was such that under ordinary circumstances a franchise would be a foregone conclusion but, by the end of 1939, the Second World War had broken out and foreign agents and spies were much more typical and topical than the antiquated criminal activities of Moriarty and his ilk. 20th Century Fox saw the Holmes series as too dubious a commercial proposition to continue on the same level of high-budget production and too difficult to relegate to their B-grade film series, so Fox dropped Sherlock Holmes. In 1942 Universal Pictures acquired the screen rights from the Conan Doyle estate and immediately put Rathbone and Bruce under contract for a dozen Holmes films, thus one studio was continuing a franchise originated by another using the same lead actors, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me again next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier with another feather from that cinematic ugly duckling known as Horrorwoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Growing up, the Rathbone films were the earliest HOLMES stories I ever saw. But now, collecting DVDs, a whole new world has been opening up to me. In the last year, I not only saw the 1916 William Gillette film adaptation of his own play, but also the greatly-expanded 1922 remake of it with John Barrymore.

But I’ve also seen the 1932 Clive Brook film “SHERLOCK HOLMES”, which, it turns out, is a direct SEQUEL to the story in the stage play. And, whatta ya know? It suddenly became obvious to me that, if anything, the 1939 “ADVENTURES…” film is actually a REMAKE of that!

It opens with Moriarty in the dock for previous crimes, but then sent to prison, after he threatens to murder the 3 people responsible for putting him there. Soon he breaks jail, murders the judge, and then hatches a scheme to frame Holmes for murdering the Scotland Yard inspector he was a rival of. Once Holmes has been arrested, he invites a whole gang of foreign criminals to run riot looting London, some of them “Chicago gangland” style– as a DIVERSION for the REAL crime, robbing The Bank Of England.

So many have said, over and over, that the ’39 film bears almost no resemblence to the 1899 stage play, and they’re right. But from what I’ve described here, it should be obvious what it DOES resemble.

At least one reviewer compared the style of the ’32 film to a “Bulldog Drummond” film, and I agree- right down to the annoying subplot of the hero putting off retirement and marriage to solve “one more” big case. Irene Adler and Violet Hunter I could see, but Alice from the play and the ’32 film… NO WAY!